Lahaina, Hawaii

Lahaina, Hawaii Lāhainā Lele | |

|---|---|

Downtown Lahaina on the waterfront prior to the 2023 fire | |

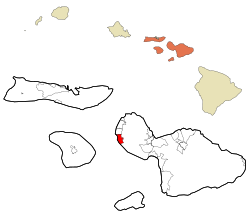

Location in Maui County and the state of Hawaii | |

| Coordinates: 20°52′26″N 156°40′39″W / 20.87389°N 156.67750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Hawaii |

| County | Maui |

| Area | |

• Total | 9.29 sq mi (24.07 km2) |

| • Land | 7.78 sq mi (20.15 km2) |

| • Water | 1.51 sq mi (3.92 km2) |

| Elevation | 3 ft (1 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 12,702 |

| • Density | 1,632/sq mi (630.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-10 (Hawaii-Aleutian) |

| ZIP Codes | 96761, 96767 |

| Area code | 808 |

| FIPS code | 15-42950 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0361678 |

Lahaina, Lāhainā (Hawaiian: Lahaina, Hawaiian: [ləˈhɐjnə], /ləˈhaɪnə/, old var. Lāhainā) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Maui County, Hawaii, United States. On the northwest coast of the island of Maui, it encompasses Lahaina town and the Kaanapali and Kapalua beach resorts. At the 2020 census (before the 2023 wildfire), Lahaina had a resident population of 12,702. The CDP spans the coast along Hawaii Route 30 from a tunnel at the south end, through Olowalu, and to the CDPs of Kaanapali and Napili-Honokowai to the north.

On August 8–9, 2023, a series of wildfires destroyed approximately 80% of Lahaina.[2] As of June 24, 2024, 102 deaths had been confirmed, with many victims identified by name.[3]

History

Name

Modern name, etymology and pronunciations

Protestant missionaries sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) began organizing a way to write the Hawaiian language with English letters between 1820–1826 after they reached Hawaii.[4][5]

"The long English sound of i is represented by ai, as in Lahaina, where the second syllable is accented, and pronounced like the English word high".[6]

According to Thrums Hawaiian Annual of 1921 the proper pronunciation of Lahaina is La-hai-ná.[7]

Lahaina has different pronunciations depending on how diacritical marks are applied.[8]

Lahaina is a combination of two Hawaiian words, “lā” which means sun, and “hainā” which means cruel. The varied spellings Lāhainā and Lahaina are commonly interchanged when written in modern english, although the traditional spelling “Lāhainā” is still considered proper.

Ancient names

Lahaina was originally called Lele in Hawaiian[9] and was known for its breadfruit trees.[10] Lele means jump or fly. Albert Pierce Taylor explains its relationship to the area as the "flying piece of kuleana, that which sticks out from the sea".[10][11]

In 1915, James N.K. Keola, in an article in Mid-Pacific Magazine entitled "Old Lahaina", wrote: "Lahaina is said to have received its name from Lā, the sun, and hainā, merciless. A bald-headed chief who lived at Kauaula Valley, while going to and fro without a hat, felt annoyed at the effects of the scorching rays of the burning sun. He looked up and gazed into the heavens and cursed at the sun thus: He keu hoi keia o ka la haina!" ("What a merciless sun!").[12] On July 13, 1920, the Star Bulletin published several theories on the name's origins that included the bald-headed chief legend, as well as theories that included the belief that the name goes back to 11th century as Laha aina (Proclaiming land).[7]

Other interpretations of the name include "day (of) sacrifice" and "day (of) explanation".[13] Inez MacPhee Ashdown (1899–1992), historian and founder of Maui Historical Society, believed the name was Lahaʻaina, meaning "land (of) prophecy", because of the number of kahuna nui (high priest) prophecies made there.[10]

Early rulers

The first mōʻī or aliʻi nui (supreme ruler) of western Maui was Haho, the son of Paumakua a huanuikalalailai. This line produced the subsequent rulers.[14]

The name Lele was adopted during the reign of Kakaʻalaneo. He held court there during joint rule with his brother Kakae, while living on a hill called Kekaʻa. They were the sons and heirs of Kaulahea I. Kakaʻalaneo first planted breadfruit trees while his son Kaululaʻau is credited with expelling ghosts from Lānaʻi and putting the island under the rule of his father and uncle. Kakae's son Kahekili I succeeded his father and uncle as ruler. Kahekili I's successor was his son Kawaokaohele, who was succeeded by his own son Piʻilani[15][16]

Piʻilani was the first ruler of the entire island of Maui when he extended his sovereignty over East Maui. The aliʻi of Hāna district accepted him as supreme ruler. Piʻilani also controlled the neighboring islands of Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, and parts of Molokaʻi.[17][18]

In 1738, Lahaina and most of West Maui were the sites of a series of battles between the forces of Kamehamehanui Aiʻluau with his uncle and ally Alapaʻi, the ali‘i nui of Hawaii Island, against his half-brother Kauhiʻaimokuakama with his ally Peleʻioholani, the ali‘i nui of Oʻahu. The war ended in a truce between Alapaʻi and Peleʻioholani and the capture and execution of Kauhiʻaimokuakama by drowning. The remains of the fallen soldiers from both sides are said to be buried in the sands of Kāʻanapali district.[19][20][21]

Western contact

On November 26, 1778 Captain James Cook's ships appeared near Maui while the island's monarch Kahekili II battled the forces of Kalaniʻōpuʻu, the ali‘i nui of Hawaii Island. He did not land on the island but was greeted by the warriors of Kalaniʻōpuʻu including a young Kamehameha I in their war canoes.[22][23] The base of the Kamehameha statue in Honolulu depicts the warrior meeting Cook off the coast of Lahaina.[24]

Kahekili II

British explorer George Vancouver visited in 1793 and unsuccessfully attempted to mediate a peace between Kahekili and Kalaniʻōpuʻu's successor Kamehameha I. During his visit, he gave a description of the constant warfare on Lahaina:[25]

The village of Raheina ... seemed to be pleasantly situated on a space of low or rather gently elevated land, in the midst of a grove of bread-fruit, cocoa-nut, and other trees...In the village the houses seemed to be numerous and to be well inhabited. A few of the natives visited the ships; these brought but little with them, and most of them were in very small miserable canoes. These circumstances strongly indicated their poverty, and proved what had been frequently asserted at Owhyhee, that Mowee and its neighbouring islands were reduced to great indigence by the wars in which for many years they had been engaged.[26]

Kamehameha I and Kamehameha II

From 1802 to 1803, Kamehameha I stationed his large fleet of peleleu war-canoes in Lahaina. While there, he wrote to the last independent ruler of Kauaʻi, Kaumualiʻi, asking him to acknowledge his overlordship. Although an invasion failed in 1804, Kaumualiʻi surrendered in 1810, uniting the Hawaiian Islands for the first time.[27][28][29] Kamehameha II resided in Lahaina from December 1819 until February 1820, when he returned to Honolulu.[28][29]

Christian missionaries

American Protestant missionaries from the ABCFM arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in 1820, setting up stations on Hawaiʻi, Oʻahu and Kauaʻi.[30] However, the first mission station on Maui was not established until 1823 by Reverend Charles Stewart and William Richards. The two men and their family accompanied Queen Keōpūolani, the wife of Kamehameha I, and her daughter Princess Nāhiʻenaʻena from Oʻahu to Lahaina. They were tasked with instructing the queen about Christianity, to which Keōpūolani converted on her deathbed. The missionaries erected a temporary church made of wooden poles and a thatched roof.[31][32] In 1824, at the chiefs' request, Betsey Stockton started the first mission school open to common people.[33] Maui Governor Hoapili ordered the construction of a stone church. The cornerstone of the Waiola Church (originally named Ebenezera or Waineʻe Church) was laid on September 14, 1828.[32][31] In 1831, missionaries founded Lahainaluna Seminary (present-day Lahainaluna High School) where Hawaiian boys and young men (among them historian David Malo) were educated in the religion and in crafts such as carpentry, printing, engraving, and agriculture. The school published the first Hawaiian language newspaper in 1834. Teachers and students were instrumental in the translation of the Bible into Hawaiian.[34]

Whaling

Lahaina was an important destination for 19th-century whalers who came to reprovision their ships with fresh water, fruit, potatoes and other vegetables. The town provided ample rest and recreation for their crew whose presence frequently led to conflicts with the local missionaries.[35] On more than one occasion the conflict became so severe that sailors rioted. The British whaling ship John Palmer in 1827 shelled Lahaina. In response, Governor Hoapili built the Old Lahaina Fort in 1831 to protect the town from unruly sailors.[36][37]

Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III resided in a traditional royal compound on the sacred island of Mokuʻula located on Mokuhinia lake in the middle of Lahaina from 1837 to 1845.[38][39] He built a two-story, Western-style palace in 1838 named Hale Piula, although it was not completed before the court moved.[40][41] During his residence, Kamehameha III signed and proclaimed the first Hawaiian constitution on October 8, 1840, at Luaʻehu, in Lahaina. The legislature's first meeting was held on April 1, 1841, also at Luaʻehu.[42][43] With the growing commercial importance of Oʻahu, Kamehameha III moved the capital to Honolulu in 1845.[44] Hale Piula was then transformed into a courthouse until it was heavily damaged in an 1858 storm. The following year, the Old Lahaina Courthouse was built as a replacement courthouse and customhouse at a site near the old fort.[32][40]

A banyan tree (Ficus benghalensis) was planted near the site of Kamehameha I's first palace by William Owen Smith on April 24, 1873, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of Christian missionaries. It survived as the oldest banyan tree in the state.[45]

20th century

On January 1, 1919, a major fire destroyed more than thirty buildings in Lahaina before it was extinguished by residents.[46] The 1919 fire led to the creation of the island-wide Maui Fire Department and adoption of fire safety standards.[46]

2023 wildfire

Over August 8–9, 2023, much of Lahaina was destroyed by a wildfire amid dry and windy conditions exacerbated by Hurricane Dora.[47] As of June 24, 2024, 102 people had been confirmed dead, with many names listed.[3] The survivors were forced to evacuate as the fire incinerated thousands of structures.[48] Pacific Disaster Center on August 11, 2023 estimated damage at US$5.52 billion.[49][50][51] Richard Bissen, the county mayor, summarized the situation: "I'm telling you, none of it's there. It's all burned to the ground."[52] Among the notable structures destroyed were the Old Lahaina Courthouse, Waiola Church, Pioneer Inn,[53] and Kimo's restaurant.[54]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 9.3 square miles (24.1 km2), of which 7.8 square miles (20.2 km2) is land and 1.5 square miles (3.9 km2), or 16%, is water.[55]

Climate

Lahaina town is one of the driest places in Hawaii, because it is in the rain shadow of Mauna Kahālāwai (West Maui Mountains). Many different climate zones define Lahaina's districts. Kaanapali is north of a wind line and has double the annual rainfall and frequent breezes. Kapalua and Napili have almost four times more annual rainfall than the town.

Lahaina has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BShs) with warm temperatures year-round, fairly wet winters, and dry summers.

| Climate data for Lahaina, Maui | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 82 (28) |

82 (28) |

83 (28) |

84 (29) |

84 (29) |

86 (30) |

87 (31) |

88 (31) |

88 (31) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

83 (28) |

85 (29) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 64 (18) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

66 (19) |

67 (19) |

69 (21) |

70 (21) |

71 (22) |

71 (22) |

70 (21) |

68 (20) |

66 (19) |

68 (20) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 54 (12) |

53 (12) |

54 (12) |

54 (12) |

57 (14) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

63 (17) |

61 (16) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

52 (11) |

52 (11) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 3.15 (80) |

2.04 (52) |

1.83 (46) |

0.74 (19) |

0.44 (11) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.14 (3.6) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.89 (23) |

1.83 (46) |

2.90 (74) |

14.63 (371.6) |

| Source: The Weather Channel[56] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 6,654 | — | |

| 1990 | 9,189 | 38.1% | |

| 2000 | 9,118 | −0.8% | |

| 2010 | 11,704 | 28.4% | |

| 2020 | 12,702 | 8.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[57] | |||

The population of Lahaina was 12,702 as of the 2020 Census.[58]

34.8% were Asian, 27.9% were White, 0.1% were Black or African American, 0.1% were Native American or Alaska Native, 10.5% were Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and 24.7% were from two or more races. Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 11.5% of the population.[58]

The population of Lahaina was 6,654 in the 1980 Census and 9,189 in the 1990 Census.[59]

Arts and culture

Before the fire, Front Street stores and restaurants attracted many visitors and was the focal point of the Lahaina Historic District. The Bailey Museum, the Lahaina Courthouse, and the Prison lined the street. The historic district included 60 historic sites managed by the Lahaina Restoration. Front Street was ranked one of the "Top Ten Greatest Streets" by the American Planning Association.[60] The Banyan Court Park featured was the largest banyan tree in the United States, reaching 60 ft (18m) in height with 46 ancillary trunks covering an area of 1.94 acres (0.78 hectares).[61]

The 1831 fort retained reconstructed remains of its 20-foot (6.1 m) walls and original cannons. Near the harbor were the historic Pioneer Inn and the Baldwin House, a historical landmark built in the 1800s.[62]

Whale-watching excursions were a popular pastime.[63] The humpback whale is dominant, although sightings of fin, minke, Bryde's, blue, and North Pacific right whales have been reported.[64]

Carthaginian II was a museum ship moored in the harbor of this former whaling port-of-call. Built in 1920 and brought to Maui in 1973, it served as a whaling museum until 2005. It was sunk in 95 feet (29 m) of water about 1⁄2-mile (0.80 km) offshore to create an artificial reef. It replaced an earlier replica of a whaler, Carthaginian, which was converted to film scenes for the 1966 movie Hawaii.

Hale Paʻi, located at Lahainaluna High School, is the site of Hawaii's first printing press, where Hawaii's first paper currency was printed in 1843. The "L" in the West Maui mountains stands for Lahainaluna High School which was built in 1904. West Maui mountain valleys are visible from town. The valleys are the backdrop for "the 5 o'clock rainbow" that appears almost every day.

Halloween was a major celebration, with crowds averaging between twenty and thirty thousand.[65] Front Street was closed to vehicles, followed by the "Keiki Parade" of costumed children. Adults in costumes join in. Halloween night in Lahaina has been termed the "Mardi Gras of the Pacific".[66] From 2008-2011 the celebration was curtailed following the objections of cultural advisers who claimed that it was an affront to Hawaiian culture, after which the County permitted the event to resume, citing economic reasons.[60]

Sports

Each November, the Lahaina Civic Center hosts the Maui Invitational, a top early-season college basketball tournament. The 2023 tournament was moved to Honolulu because of the wildfires.

The Lahaina Aquatic Center hosts swim meets and water polo.[67] Tennis events also take place.

Lahaina hosts the finish of the Victoria to Maui Yacht Race, which starts in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. This race started in the 1960s and is held biannually.

The Plantation Course at Kapalua hosts the PGA Tour's Sentry Tournament of Champions every January.

Popular culture

Movies, literature, and songs about, or filmed in Lahaina include:

- 1959 - James A. Michener wrote "Hawaii", a historical fiction novel where much of it was set in Lahaina. It was the setting for the first Christian missionaries to Hawaii in the 1800s.

- 1966 – Kui Lee wrote and sang "Lahaina Luna."

- 1973 – Loggins and Messina had their song "Lahaina" lead off their 1973 album Full Sail.

- 1976 - The Eagles song "The Last Resort", on the album Hotel California, includes lyrics about sailing to Lahaina and about the Jesus Coming Soon Church.

- 2000 – Born and raised in Lahaina, Willie K wrote and sang "Katchi Katchi music Makawao" with lyrics that include "play the conga drums down in Lahaina".[68]

- 2010 – Hereafter, by Clint Eastwood, in which a tsunami ravages Front Street.[69]

- 2023 – The Doobie Brothers released a new charity song featuring Mick Fleetwood, Henry Kapono, and Jake Shimabukuro to raise money after the 2023 Hawaii wildfires.

Gallery

- Lahaina Harbor in 2002

- Lahaina in 2005

- Lahaina in 2010

- Lahaina Aquatic Center in 2018

See also

- Lahaina Historic District

- Lahaina Noon – Tropical solar phenomenon

- Living Lahaina – American reality television series

Notes

References

- Citations

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ Tanyos, Faris (August 17, 2023). "Lahaina residents reckon with destruction, loss as arduous search for victims continues". CBS News. U.S. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Nuttle, Matthew (August 1, 2024). "All of the people who perished in the Maui fire". Island News. KITV.

- ^ Schütz 1995, pp. 98–133.

- ^ Tracy 1842, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Tracy 1842, p. 123.

- ^ a b Thrum 1921, p. 86.

- ^ U.S., Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration and Hawaii Department of Transportation 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Fornander 1917, p. 484.

- ^ a b c U.S., Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration and Hawaii Department of Transportation 1991, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Taylor 1929, pp. 35–68.

- ^ Keola 1915, pp. 571–575.

- ^ Clark 1989, p. 57.

- ^ Fornander 1880, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Fornander 1880, pp. 82–87.

- ^ Beckwith 1970, p. 884.

- ^ Kirch & McCoy 2023, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Fornander 1880, p. 87.

- ^ Fornander 1880, pp. 140–142, 214.

- ^ Keola, James N. K. (1913). "Old Lahaina". The Mid-Pacific Magazine. Vol. 10. Honolulu: T. H., A. H. Ford; Pan-Pacific Union, Pan-Pacific Research Institution. pp. 569–575. OCLC 45158315. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Sterling, Elspeth P. (1998). Sites of Maui. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-930897-97-0. OCLC 37608159.

- ^ Kirch 2014, p. 213.

- ^ Beaglehole 1992, p. 638.

- ^ Kamehiro 2009, p. 92.

- ^ Fornander 1880, pp. 250–253.

- ^ Fornander 1880, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Kuykendall 1965, pp. 48–51.

- ^ a b Keola 1915, p. 573.

- ^ a b Taylor 1929, p. 40.

- ^ Kuykendall 1965, pp. 100–104.

- ^ a b Williams 2013, pp. 122–129.

- ^ a b c Russell A. Apple (December 21, 1973). "Lahaina Historic District National Historical Landmark update". Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Dodd 1984, pp. 358–360.

- ^ Taylor 1929, pp. 52–54.

- ^ "Lahaina Harbor History". Hawaii Harbors Network. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Busch 1993, pp. 91–118.

- ^ Maui Historical Society. (1971) [1961]. Lahaina Historical Guide. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle.

- ^ Klieger 1998, p. ix.

- ^ Kam 2022, pp. 38–40.

- ^ a b Kam 2022, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Klieger 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Kamakau 1992, pp. 370, 398.

- ^ Spaulding 1930, pp. 25–33.

- ^ Bartels, Jim. "ʻIolani Palace". Pacific World. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Clark 2001, p. 23.

- ^ a b Hurley, Timothy (August 10, 2023). "Lahaina's historic and cultural treasures go up in smoke". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Much of historic Lahaina town believed destroyed as huge wildfire sends people fleeing into water". Hawaii News Now. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ "At least 36 people dead in Maui wildfires: Hawaii live updates". The Independent. August 10, 2023. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Pacific Disaster Center and the Federal Emergency Management Agency releases Fire Damage. County of Maui (Report). August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "The wildfires scorching Maui have killed at least 53 people and destroyed hundreds of buildings, officials say". CNN. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "FEMA lends a hand, but Maui fire losses estimated in the billions; officials release first names of people killed: Aug. 15 updates". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Koenig, Ravenna; Treisman, Rachel (August 11, 2023). "Officials say some 1,000 could be missing after Maui wildfires, but it's hard to say". NPR. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Schaefers, Allison (August 9, 2023). "Century-old Pioneer Inn among property casualties of West Maui wildfires". The Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Graff, Amy (August 11, 2023). "'We will rebuild': The birthplace of Hula Pie lost in Maui fire". sfgate. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Lahaina CDP, Hawaii". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ "Monthly Weather-Lahaina, HI". Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b "Lahaina CDP, Hawaii". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Table 1.-- 1990 CENSUS TRACT NAMES AND 1980 AND 1990 RESIDENT POPULATION FOR THE STATE OF HAWAII" (PDF). Files.hawaii.gov. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ a b Osher, Wendy (October 4, 2011). "Maui's Front Street Named to Top 10 Great Streets for 2011". Maui Now. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011.

- ^ Debusmann Jr, Bernd (August 11, 2023). "Lahaina: Famous banyan tree and centuries-old church hit by fires". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Silverman, Sam (August 10, 2023). "Baldwin House, Maui's Oldest Home, Destroyed By Wildfires". Entrepreneur. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "Maui Whale Watching Guide | Humpback Whales in Hawaii". Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Marine Mammals". April 23, 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "In Lahaina, a monumental Maui Halloween" Archived 2007-12-28 at the Wayback Machine from Island Life October 29, 2004

- ^ "Halloween Destinations". Travel Channel. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "Lahaina Aquatic Center". mauicounty.gov. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Hawaii mourns the loss of amazingly talented musician William Awihilima Kahaiali'i". lahainanews.com. May 28, 2020. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Maui in the Movies | Maui Time". mauitime.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Books

- Beckwith, Martha Warren (1970). Hawaiian Mythology. Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 9780870220623. OCLC 96119.

- Beaglehole, J. C. (1992). The Life of Captain James Cook. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2009-0.

- Busch, Briton C. (1993). "Whalemen, Missionaries, and the Practice of Christianity in the Nineteenth-Century Pacific" (PDF). The Hawaiian Journal of History. 27. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 91–118. hdl:10524/499. OCLC 60626541. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 2, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Clark, John R. K. (1989). The Beaches of Maui County. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824812461. OCLC 19393830.

- Clark, John R. K. Clark (2001). Hawai'i place names: shores, beaches, and surf sites. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2451-8. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- Dodd, Carol Santoki (1984). "Betsey Stockton". In Peterson, Barbara Bennett (ed.). Notable Women of Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 358–360. ISBN 978-0-8248-0820-4. OCLC 11030010. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Fornander, Abraham (1880). An account of the Polynesian race its origins and migrations and the ancient history of the Hawaiian people to the times of Kamehameha I Volume 1 1878. Ludgate Hill, London, England: Trübner and Co. ISBN 978-1528705028. OCLC 581126109.

- Fornander, Abraham (1917). Fornander Collection of Hawaiian Antiquities and Folk-Lore. Honolulu, Hawaii: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 9781330368510. OCLC 3354092.

- Kam, Ralph Thomas (2022). Lost Palaces of Hawai'i: Royal Residences of the Kingdom Period. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-8811-4.

- Kamakau, Samuel (1992) [1961]. Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii (Revised ed.). Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-014-1. OCLC 25008795.

- Kamehiro, Stacy L. (2009). The Arts of Kingship: Hawaiian Art and National Culture of the Kalākaua Era. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3263-6. OCLC 663885792.

- Keola, James N.K. (1915). "Old Lahaina". Mid-Pacific Magazine. 10 (1).

- Kalākaua, David (1976). The Legends and Myths of Hawaii. Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1718745308. OCLC 646861314.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (2014). Kua'āina Kahiko: Life and Land in Ancient Kahikinui, Maui. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-4020-4.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton; McCoy, Mark D. (2023). Feathered Gods and Fishhooks: The Archaeology of Ancient Hawai'i Revised edition. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824894467. OCLC 40347741.

- Klieger, P. Christiaan (1998). Mokuʻula: Maui's Sacred Island. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 978-1-58178-002-4. OCLC 40142899.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965) [1938]. The Hawaiian Kingdom 1778–1854, Foundation and Transformation. Vol. 1. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-431-X. OCLC 47008868.

- Pukui, Mary Kawena; Elbert, Samuel H. (1976). Place Names of Hawaii: Revised and Expanded Edition. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824805241. OCLC 1253313911.

- Spaulding, Thomas Marshall (1930). "Early Years of the Hawaiian Legislature". Thirty-Eighth Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society for the Year 1929. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 25–33. hdl:10524/33. OCLC 2105039.

- Taylor, Albert Pierce (1929). "Lahaina: The Versailles of Old Hawaii". Thirty-Seventh Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society for the Year 1928. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. hdl:10524/92.

- Thrum, Thomas George (1921). Thrum's Hawaiian Annual. Star-Bulletin Printing Co.

- Tracy, Joseph (1842). History of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. M.W. Dodd.

- Turner, Charlotte L. (1922). "Sketches of Lahaina". The Friend. 91 (12). Samuel C. Damon.

- U.S., Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration and Hawaii Department of Transportation (1991). Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement FAP-30 (Honoapiilani Highway) Realignment, Puamana to Honokowai, Lahaina (Report). State of Hawaii.

- Schütz, Albert J. (1995). The Voices of Eden: A History of Hawaiian Language Studies. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1637-7.

- Williams, Ronald Jr. (December 2013). Claiming Christianity: The Struggle Over God and Nation in Hawaiʻi, 1880–1900 (PDF) (Thesis). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. pp. 122–129. hdl:10125/42321.