Kimberichnus

| Kimberichnus Temporal range: Same time range as its maker, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Trace fossil classification | |

| Ichnogenus: | †Kimberichnus Ivantsov, 2013 |

| Type ichnospecies | |

| †Kimberichnus terruzi | |

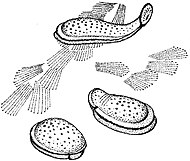

Kimberichnus is an ichnofossil associated with the early bilaterian Kimberella.[1][2] It is known mostly from shallow marine Ediacaran sediments, often occurring alongside its producer.[3] Kimberichnus often occurs in Russia and South Australia, where it is most abundant in the shape of multiple arcuate sets of ridges with fan-shaped arrangements.[2][4]

Description

Kimberichnus traces often occur alongside the death masks of Kimberella; the traces represent possibly the oldest known evidence of trace fossils that are associated with a bilaterian maker.[4][5] The traces occur in the Ediacaran sediments of the Russian White Sea and in South Australia, Kimberichnus was described from Russia.[2] They most often occur as simple arcuate ridges arranged in sets, with an arrangement similar to that of fans; it is thought that these traces came from Kimberella rasping the microbial mat underneath it with its teethed Proboscis[3]

The feeding patterns that are seen in these traces exclude any Arthropodal origin, they instead point to a creator that was most likely systematically excavating nutrients/food off of the microbial mats.[4] Even though organisms at the time would move over the traces and slightly disturb them, it would not disturb them to the point that they will get deformed; this is because of the multiple layers of Microbes that made up the mats . The occurrence of both the traces maker and the trace itself in the Ediacaran period supports claims that bilaterians were already globally distributed and were able to make traces of grazing.[4]

Theoretical importance

| Part of a series on |

| The Cambrian explosion |

|---|

|

The Cambrian explosion, which began approximately 543 million years ago and concluded around 518 million years ago, marked a significant increase in animal diversity, particularly in the development of distinct body plans.[6] This rapid diversification posed a challenge to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, as mid-19th century scientists had already discovered Early Cambrian fossils that highlighted the abrupt appearance of complex life forms.[7]

Kimberichnus is considered an important step in this evolutionary period. Evidence indicates that Kimberella grazed on microbial mats using a proboscis with rows of teeth, leaving behind trace fossils known as Kimberichnus. These traces share similarities with Radulichnus, a comparable trace fossil from later geological periods.[8] The association of Kimberichnus with a radula-like structure supports the hypothesis that Kimberella may have been an early mollusk or a close relative. This is particularly significant because radulae, being soft and rarely fossilized, provide limited direct evidence in the fossil record.[8]

See also

References

- ^ Chemostratigraphy Across Major Chronological Boundaries. John Wiley & Sons. 18 December 2018. ISBN 978-1-119-38248-5.

- ^ a b c The Invertebrate Tree of Life. Princeton University Press. 3 March 2020. ISBN 978-0-691-17025-1.

- ^ a b The Trace-Fossil Record of Major Evolutionary Events: Volume 1: Precambrian and Paleozoic. Springer. 17 November 2016. ISBN 978-94-017-9600-2.

- ^ a b c d Gehling, James G.; Runnegar, Bruce N.; Droser, Mary L. (2014). "Scratch Traces of Large Ediacara Bilaterian Animals". Journal of Paleontology. 88 (2): 284–298. doi:10.1666/13-054. S2CID 140559034.

- ^ Annelida Basal Groups and Pleistoannelida, Sedentaria I. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. 18 March 2019. ISBN 978-3-11-038178-8.

- ^ Cowen, R. (2000). History of Life (3rd ed.). Blackwell Science. p. 63. ISBN 0-632-04444-6.

- ^ Darwin, C (1859). On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection. Murray, London, United Kingdom. pp. 315–316.

- ^ a b Fedonkin, M.A.; Simonetta, A.; Ivantsov, A.Y. "New data on Kimberella, the Vendian mollusc-like organism (White Sea region, Russia): palaeoecological and evolutionary implications". The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota. pp. 157–179. doi:10.1144/SP286.12.