Kafr Bir'im

Kafr Bir'im كفر برعم Kefr Berem | |

|---|---|

The church of Kafr Bir'im | |

| Etymology: The village of Bir'im[1] | |

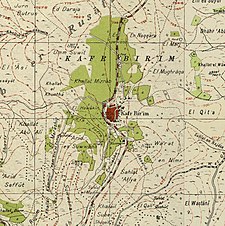

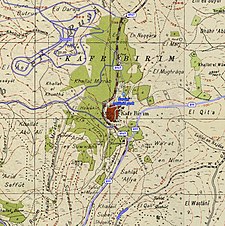

A series of historical maps of the area around Kafr Bir'im (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 33°02′37″N 35°24′51″E / 33.04361°N 35.41417°E | |

| Palestine grid | 189/272 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Safad |

| Date of depopulation | early November 1948[3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 12,250 dunams (12.25 km2 or 4.73 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

• Total | 710[2] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Expulsion by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Bar'am National Park, Bar'am[4][5] Dovev[5] |

Kafr Bir'im, also Kefr Berem (Arabic: كفر برعم, Hebrew: כְּפַר בִּרְעָם), was a former village in Mandatory Palestine, located in modern-day northern Israel, 4 kilometers (2.5 mi) south of the Lebanese border and 11.5 kilometers (7.1 mi) northwest of Safed. The village was situated 750 meters (2,460 ft) above sea level. "The village stood on a rocky hill only a little higher than the surrounding area and faced north and west."[6]

In ancient times, it was a Jewish village known as Kfar Bar'am. It became culturally Arabized during the Middle Ages.[citation needed] In the early Ottoman era it was wholly Muslim. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was noted as a predominantly Maronite Christian village. A church overlooking it at an elevation of 752 meters (2,467 ft) was built on the ruins of an older church destroyed in the earthquake of 1837. In 1945, it had a population of 710 people, most of them Christians.[6]

The Palestinian Christian villagers were expelled by Zionist forces during the 1948 Palestine war. A few years later, on September 16, 1953 the village was destroyed by the Israeli military in order to prevent the villagers' return and in defiance of an Israeli Supreme Court decision recognizing the villager's right to return to their homes.[7][8][9][10] By 1992, the only standing structure was the church and belltower.[6][additional citation(s) needed]

History

Antiquity

The village was originally Kfar Bar'am, a Jewish village which was established in ancient times.[11] The remains of the 3rd-century Kfar Bar'am synagogue on the outskirts of the town are still visible, as is another ruined synagogue in the center of the village.[12][13]

Among the findings here is an Aramaic bronze amulet inscribed in Hebrew letters, believed to offer protection to "Yudan, son of Nonna". This artifact was unearthed during excavations led by Aviam in 1998 at the small synagogue near Bar'am.[14]

Middle Ages

A visitor in the thirteenth century described an Arab village containing the remains of two ancient synagogues.[15]

Ottoman period

In 1596, Kafr Bir'im appeared in Ottoman tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Jira, part of Sanjak Safad. It had a population of 114 households and 22 bachelors; all noted as Muslim. The villagers paid taxes on wheat, barley, goats and beehives, but most of the taxes were paid as a fixed sum; total revenue was 13,400 akçe.[16][17]

Kafr Bir'im was badly damaged in the Galilee earthquake of 1837. The local church and a row of columns from the ancient synagogue collapsed.[18] In 1838 it was noted as a Maronite village in the Safad region.[19]

In 1852 it was estimated that the village had a population of 160 males, all Maronites and Melkites.[20] During the 1860 civil war in Lebanon, Muslims and Druzes attacked the Christian village.[21]

In 1881, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described the village as being built of stone, surrounded by gardens, olive trees and vineyards, with a population of between 300 and 500.[22]

A population list from about 1887 showed Kefr Bir’im to have about 1,285 inhabitants, all Christian.[23]

British rule

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Kufr Berim had a population of 469; all Maronite Christians.[24][25] By the 1931 census there were 554 people in the village; 547 Christians and 7 Muslims, in a total of 132 houses.[26]

In the 1945 statistics, Kafr Bir'im had a population of 710, consisting of 10 Muslims and 700 Christians,[2] with 12,250 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey.[27] Of this, 1,101 dunams were irrigated or used for plantations, 3,718 for cereals,[28] while 96 dunams were classified as urban land.[29]

The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question describes the pre-1948 modern period in Kafr Bir'im thus: "Their houses, made of stone and mud, were built close together. Some of the land was forested. Agriculture, irrigated from the abundant springs, was the primary occupation of the villagers, who were especially active in olive and fruit cultivation."[6]

Some villagers assisted European Jews traveling to Palestine by way of Lebanon by distracting British police officers, who were restricting Jewish immigration.[30]

The village population in 1948 was estimated as 1,050 inhabitants.[citation needed]

Israeli rule

Kafr Bir'im was captured by the Haganah on October 31, 1948 during Operation Hiram. In November 1948 most of the Palestinian inhabitants were expelled until the military operation was complete, and none were subsequently permitted to return.[31] Families camped in the orchards outside the village until Bechor Sheetrit ordered them to relocate to nearby Jish in the homes emptied by the expelled Muslim villagers. Around 250 Bir'imites could not find homes in Jish, many of whom crossed the border to Lebanon.[30]

Today the villagers and their descendants number about 2,000 people in Israel. In addition, there are villagers and descendants in Lebanon and in western countries.[32] The majority of the villagers remained in the territory that became the state of Israel.[33]

In 1949, with cross-border infiltration a frequent occurrence, Israel did not allow the villagers to return to Bir'im on the grounds that Jewish settlement at the place would deter infiltration.[34][clarification needed] Kibbutz Bar'am was established by demobilized soldiers on the lands of the village.[citation needed]

In 1953, the residents of former Kafr Bir'im appealed to the Supreme Court of Israel to return to their village. The court ruled that the authorities must answer to why they were not allowed to return. In September, the court ruled that the villagers should be allowed to return to their homes. However after the court ruling, an Israeli Air Force bombing on September 16, 1953 "levelled" the village and 1,170 hectares of land were expropriated by the state.[6][7][9] Villagers recount watching the firebombing of the village from a hill in Jish they later called "Bir'imites wailing place."[30] Ultimately, the court's decision to allow the Palestinian villagers to return was not enforced.[35]

In his book Blood Brothers, Father Elias Chacour, who was a child away at school at the time, records the story of what happened, as told to him by his brothers:

For the second time, the village elders marched across the hill and presented the order to the Zionist soldiers...Without question or dispute, the commanding officer read the order. He shrugged. 'This is fine...We need some time to pull out. You can return on the 25th.'

On Christmas! What an incredible Christmas gift for the village. The elders fairly ran across the hill to Gish to spread the news. At long last they would all be going home. The Christmas Eve vigil became a celebration of thanksgiving and joyful praise. On Christmas morning...bundled in sweaters and old coats supplied by the Bishop's relief workers, the villagers gathered in the first light of day...Mother, Father, Wardi, and my brothers all joined in singing a jubilant Christmas hymn as they mounted the hill...At the top of the hill their hymn trailed into silence...Why were the soldiers still there? In the distance, a soldier shouted, and they realized they had been seen. A cannon blast sheared the silence. Then another—a third...Tank shells shrieked into the village, exploding in fiery destruction. Houses blew apart like paper. Stones and dust flew amid the red flames and billowing black smoke. One shell slammed into the side of the church, caving in a thick stone wall and blowing off half the roof. The bell tower teetered, the bronze bell knelling, and somehow held amid the dust clouds and cannon fire... Then all was silent—except for the weeping of women and the terrified screams of babies and children.

Mother and Father stood shaking, huddled together with Wardi and my brothers. In a numbness of horror, they watched as bulldozers plowed through the ruins, knocking down much of what had not already blown apart or tumbled. At last, Father said—to my brothers or to God, they were never sure—'Forgive them.' Then he led them back to Gish.

— Father Elias Chacour

The leader of Melkite Greek Catholics in Israel, Archbishop Georgios Hakim, alerted the Vatican and other church authorities, and the Israeli government offered the villagers compensation. Archbishop Hakim accepted compensation for the land belonging to the village church.[37]

In the summer of 1972, the villagers of Kafr Bir'im and Iqrit went back to repair their churches and refused to leave. Their action was supported by archbishop Hakim's successor, Archbishop Joseph Raya. The police removed them by force. The government barred the return of the villagers so as not to create a precedent.[38] In August 1972, a large group of Israeli Jews went to Kafr Bir'im and Iqrit to show solidarity with the villagers. Several thousand turned out for a demonstration in Jerusalem.[39][30] The Israeli authorities said most of the inhabitants of the village had received compensation for their losses, but the villagers said they had only been compensated for small portions of their holdings.[40] In 1972, the government rescinded all "closed regions" laws in the country, but then reinstated these laws for the two villages Kafr Bir'im and Iqrit.

This was met with criticism by the opposition parties. In the 1977 election campaign Menachem Begin, then leader of the right-wing Likud party, promised the villagers that they could return home if he was elected. This promise became a great embarrassment to him after he had won, and a decision on the issue was postponed as long as possible. It was left to his agriculture minister to reveal to the public that a special cabinet committee had decided that the villagers of Kafr Bir'im and Iqrit would not be allowed to return.[41]

Families displaced from Bir'im to nearby areas return to the village ruins to celebrate holidays and special events at the village church, as well as pick fruit and forage from the remaining gardens. Summer camps (called "roots and belonging") for children of the displaced families began in the 1970's and were held annually from the mid-80's onward, and served as a model for other internally displaced Palestinian communities.[30]

On the occasion of official visits to Israel by popes John Paul II in 2000 and Benedict XVI in 2009, the villagers made public appeals to the Vatican for help in their endeavour to return to Kafr Bir'im, but have so far remained unsuccessful.[42][43]

Legacy

The operational name of the Munich massacre of Israeli athletes in 1972 was named after this village and Iqrit.[44]

The Palestinian artist Hanna Fuad Farah made memory of Kafr Bir'im a central theme of his work.[45]

Priest Elias Chacour, who was expelled from Kafr Bir'im at age 6, wrote of his return to the village ruins by way of Bar'am National Park in his autobiography.[30]

Kafr Bir'im is among the demolished Palestinian villages for which commemorative Marches of Return have taken place, such as those organized by the Association for the Defence of the Rights of the Internally Displaced.[46]

See also

- Correcting a Mistake: Jews and Arabs in Palestine/Israel, 1936-1956

- Present absentee

- Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 76

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 10

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xvi, village #38. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xxii, settlement #160

- ^ a b Khalidi, 1992, p. 461

- ^ a b c d e "Kafr Bir'im — كَفْر بِرْعِم". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 2023-12-05.

- ^ a b Sabri Jiryis: "Kouetz 307 (27. Aug. 1953): 1419"

- ^ Returning to Kafr Bir’im, 2006, BADIL Resource Center

- ^ a b Ryan, Joseph L. (1973-07-01). "Refugees Within Israel: The Case of the Villagers of Kafr Bir'im and Iqrit". Journal of Palestine Studies. 2 (4). University of California Press: 62–63. doi:10.2307/2535631. ISSN 0377-919X. JSTOR 2535631.

- ^ Hadawi, Sami. Bitter Harvest: Palestine between 1914-1979. Revised edition. New York: The Caravan Books, 1979, 150.

- ^ Judaism in late antiquity, Jacob Neusner, Bertold Spuler, Hady R Idris, BRILL, 2001, p. 155

- ^ Fine, 2005, pp. 13-14

- ^ The Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon of the Old Testament, By Ludwig Köhler, Walter Baumgartner, Johann Jakob Stamm, Mervyn Edwin John Richardson, Benedikt Hartmann, Brill, 1999, p. 1646

- ^ "XXVI. Barʿam", Volume 5/Part 1 Galilaea and Northern Regions: 5876-6924, De Gruyter, pp. 157–158, 2023-03-20, doi:10.1515/9783110715774-034, ISBN 978-3-11-071577-4, retrieved 2024-02-29

- ^ Judaism in late antiquity, Jacob Neusner, Bertold Spuler, Hady R Idris, BRILL, 2001, p. 155

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 175

- ^ Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine writes that the register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9

- ^ "1837 earthquake in southern Lebanon and northern Israel N. N. Ambraseys, in Annali di Geofisica, Aug. 1997, p. 933" (PDF). Retrieved Jun 6, 2020.

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 134

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1856, pp. 68-71

- ^ Yazbak, 1998, p. 204

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 198. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 460

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 190

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XI, p. 41

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XVI, Sub-district of Safad, p. 51

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 105

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 70

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 119

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 169

- ^ a b c d e f Weaver, Alain Epp (2014). Mapping exile and return: Palestinian dispossession and a political theology for a shared future. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-7012-3. OCLC 858897113.

- ^ Justice for Ikrit and Biram, Haaretz October 10, 2001

- ^ "Birem.org". Archived from the original on September 21, 2005. Retrieved Jun 6, 2020.

- ^ Zu'bi, Himmat. "Present Absentees in Israel". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 2023-12-05.

- ^ Morris, 1997, p. 124

- ^ Shehadeh, Raja (2023-08-03). We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir. Profile Books Limited. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-78816-998-1.

- ^ Chacour, E.; Hazard, D.; Baker, J. (2022). "5". Blood Brothers: The Dramatic Story of a Palestinian Christian Working for Peace in Israel. Baker Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4934-3753-5. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ Sabri Jiryis: Israel Government Yearbook 5725 (1964):32

- ^ Sabri Jiryis: Haaretz 24 July 1972, Yedioth Aharonoth, 30 June 1972

- ^ Sabri Jiryis and Chacours autobiography

- ^ Sabri Jiryis: compensation for only 91.6 out of 1,565.0 acres (6.333 km2) had been given in Ikrit, in Kafr Bir'im only "negligible" amounts

- ^ Jerusalem Post, 18 January 1979, ref. in Gilmour, p.103

- ^ AFP (21 May 2014). "Under pressure, Israel's Palestinian Christians reach out to pope". Maan News. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Alessandra Stanley (25 March 2000). "A New Sermon of Peace on the Mount". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Morris & Black, 1991, p. 270

- ^ Laïdi-Hanieh, Adila. "Palestinian Visual Arts (IV)". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 2023-12-05.

- ^ Charif, Maher. "Meanings of the Nakba". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 2023-12-05.

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, M. (2000). Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948. Maxine Kaufman-Lacusta (translator). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-92882-2.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Chacour, E.: "Blood Brothers. A Palestinian Struggles for Reconciliation in the Middle East" ISBN 0-8007-9321-8 with Hazard, David, and Baker III, James A., Secretary (Foreword by) 2nd Expanded ed. 2003.

- Dalrymple, W. (1997): From the Holy Mountain, Harper Collins, ISBN 0-00-255509-3 p. 268-9, 271, 275-6, 363, 365-72. Dalrymple interviewed Sarah Daou from Kafr Bir'im and goes there to find her relatives.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Fine, S. (2005). Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman world: toward a new Jewish archaeology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521844916.

- Gilmour, David (1982). Dispossessed. The Ordeal of the Palestinians. Sphere books. ISBN 9780722138427. pp. 102–103

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 3: Galilee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Jiryis, S.: The Arabs in Israel 1st American edition 1976 ISBN 0-85345-377-2 (updated from the 1966 ed.) With a foreword by Noam Chomsky. (First English edition; Beirut, Institute for Palestine Studies, 1968). Chapter 4.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. and Black, I. (1991): Israel's Secret Wars: A History of Israel's Intelligence Services (Grove Press, 1991) ISBN 0-8021-1159-9

- Morris, B. (1994). 1948 and after; Israel and the Palestinians. Oxford University Press.

- Morris, B. (1997). Israel's Border Wars, 1949 - 1956. Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829262-7.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century (PhD). Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Yazbak, M. (1998). Haifa in the Late Ottoman Period, A Muslim Town in Transition, 1864–1914. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 90-04-11051-8.

External links

- Kufr Birim, from Electronic Intifada

- Welcome To Kafr Bir'im

- Kafr Bir'im, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Kafr Bir'im, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Kufr Bir3em, from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

- Kafr Bir’im, Dr. Khalil Rizk.

- A visit to Bir’im with the Bir'im children's summer camp[usurped] by Miki Levi (31/7/2004), from Zochrot

- The right of return, colored in pink[usurped] by Ronit Sela, Bir'im (6/8/2005) from Zochrot

- Visit to Birem Summer Camp[usurped] by Eitan Bronstein, (9.8.2007) from Zochrot