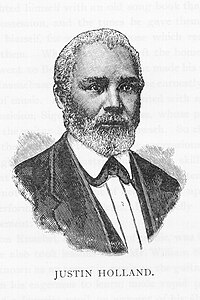

Justin Holland

| Justin Holland | |

|---|---|

Portrait from the book Men of Mark (1887). | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | William J.H. White[1] |

| Born | July 26, 1819 Norfolk County, Virginia |

| Died | March 24, 1887 (aged 67) New Orleans, Louisiana[2] |

| Genres | classical |

| Occupation(s) | music teacher, arranger, composer, textbook author; civil rights activist |

| Instrument | guitar |

| Years active | 1845–87 |

Justin Holland (July 26, 1819[3] – March 24, 1887[4]) was an American classical guitarist,[5] a music teacher,[6] a community leader,[7] an African American man who worked with Euro-American people to help slaves on the Underground Railroad,[8] and an activist for equal rights for African Americans.[7][9]

Holland was known nationally, not only as a musician but also as a civil rights activist who worked in the same national circles as Frederick Douglass.[10] His goal was to develop his personal growth, in order to stand as an example for others to see.[3] As a teacher, he deliberately chose a "cautious and circumspect" bearing, keeping his relationships with students strictly professional.[11] He chose work that was considered honorable and held high standards, and the professional respect that accompanied his position aided his civil rights goals.[6]

A measure of his success in showcasing the admirable African American to the world came after he died, when he was given eulogies, by white people as well as African Americans, about his skill as a musician and his personal character.[2]

Background

Holland grew up in Norfolk County, Virginia, the son of a farmer, Exum Holland.[5][3] He showed talent for music while he was young, writing music to go with pre-existing lyrics, but there were few opportunities to hear music or learn to play where he lived.[1] His chief opportunity was at church.[1][5]

When he was 14 years old in 1833 his parents both died, and he left home for Boston.[5][3] He then moved on to the nearby town of Chelsea, Massachusetts, staying there for several years.[5] In Boston he met Signor Mariano Perez, a Spanish musician and "clever performer on the guitar."[5][9] Perez taught Holland to play guitar.[5] Another music teacher for Holland was Simon Knabel, a member of Ned Kendall's Brass Band.[5] Knabel had some success arranging music.[5] Holland also studied under William Schubert, also of Kendall's band.[5][9] Schubert was a "brilliant performer on the guitar" and Holland made good progress on his instrument.[5] Another teacher, a Scottishman named Pollock, taught him how to play the concert flute.[5]

Being young and not living with parents, Holland had to work as a laborer to support himself while he learned his craft.[5] The work was hard, the education took money, and he gave up sleep in order to have time to practice.[5]

College and career

In 1841 (about age 20) he entered Oberlin College in northern Ohio.[5] He stayed there for two years.[5] Afterward, he traveled to Mexico in order to learn Spanish.[5] He wanted to know more about Spanish guitar and the methods of Fernando Sor, Dionisio Aguado y García and others, and needed to be able to understand Spanish to read their works.[5][6] Holland returned to Oberlin in 1845, married, and moved to Cleveland, Ohio, becoming "The first black professional in Cleveland."[5][12]

Holland had at least two children. His daughter Clara Monteith Holland was an accomplished pianist and guitarist. Justin Minor Holland, Jr. also a guitarist, was a teacher, composer and the author of Method for the Guitar, published in 1888.[13]

In Cleveland he gave guitar lessons and found a demand for his services.[5] He settled then and devoted himself to teaching and arranging music for the guitar.[5] He became known nationally for his arrangements, which were issued in collections of approximately 20 pieces, including Winter Evenings, Gems for the Guitar, Boquet of Melodies, and Flowers of Melody.[5] He also arranged about 30 duos for two guitars and another 30 for guitar and violin.[5] It was his music method books that gave him his fame as "one of America's most influential guitar pedagogues."[9] Holland taught with a conservative approach, looking to European guitar masters and their traditional techniques.[9] His method books were Modern Method for the Guitar (1874) and Comprehensive Method for the Guitar (1876).[5][8][9]

Civil rights

Holland was born to free black parents in Norfolk County, Virginia, in 1819.[3] The area had adopted a liberal attitude toward African Americans, which had resulted in a large number being free.[3] That attitude was changing, however, as the demand for labor for producing cotton grew stronger.[3] Slavery was becoming based on the concept of racial inferiority, and the presence of successful, free African Americans contradicted this.[3] Also, the presence of free Blacks showed slaves that freedom was possible.[3]

Starting with himself, Holland would work all his life, working to better the conditions for African Americans.[3] He attended a college, Oberlin College, at a time when very few African Americans could get a college education.[14] He studied languages, learning Spanish, French, Italian and German.[15] As an adult, between 1848 and 1854, he acted as an assistant secretary and member of council at National and State Negro Conventions.[16] He was secretary of the "Colored Americans of Cleveland".[10] He worked with the Underground Railroad.[8] He also worked toward establishing a free-black colony in South America, acting as secretary for the Central American Land Company.[16]

In 1845 he moved to the Cleveland, Ohio, in the Western Reserve, where he worked on his dream of complete acceptance for African Americans by white Americans, with complete equality.[6] Cleveland was another place where white people were sympathetic toward African Americans.[8] He saw the area as a place that gave him the opportunity to work toward that goal.[17] He consciously embraced education and assimilation as the best ways to overcome racial barriers and prejudices.[3] He looked to European culture as a source of admirable standards (and hoped that middle-class Americans around him would associate him with those standards as well.)[10] He spoke of his own music in terms of European excellence, teaching the "correct system" to fret the strings on the guitar, as done by "the best Masters of Europe."[10] He also wrote a 324-page treatise on subjects of moral reform.[5]

Not only working on himself, he tried to help other black people, assisting with the Underground Railroad.[8] When the Freemasons would not accept African Americans into their society, or recognize the free-black Prince Hall Masons, he corresponded with masonry groups in Europe, seeking support and recognition there.[2] He gained recognitions from Masons in several European countries (Germany, France, Italy, Hungary) and two from the Americas (Peru and the Dominican Republic).[2]

Works

The following works are online at the Library of Congress:[18]

Arranged

- La prima donna waltz, 1854

- Fra Diavolo, 1858

- Fille du regiment, 1868

- Lucia di Lamermoor, 1868

- Lucrezia Borgia, 1868

- Norma, 1868

- Oberon, 1868

- Rigoletto, 1868

- Giertrude's dream waltz, 1871

- Delta Kappa Epsilon march, 1881

Works by Justin Holland on IMSLP.

References

- ^ a b c Clemenson 2006, p. 2

- ^ a b c d Clemenson 2006, p. 7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Clemenson 2006, p. 1

- ^ "VA-WP13 Justin Holland". Historical Markers. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Bone 1914, pp. 149–150

- ^ a b c d Clemenson 2006, p. 3

- ^ a b Clemenson 2006, pp. 1, 5–6

- ^ a b c d e Clemenson 2006, p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f Noonan 2008, pp. 61–62

- ^ a b c d Clemenson 2006, p. 5

- ^ Clemenson 2006, pp. 4–5

- ^ Clemenson 2006, pp. 1, 3

- ^ Noval, Elliot. "Justin Holland: an introduction" (PDF). Guitarist Newsletter. Minnesota Guitar Society. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Clemenson 2006, pp. 2–3

- ^ Justin Holland (1819–1887)

- ^ a b Clemenson 2006, pp. 5–6

- ^ Clemenson 2006, pp. 3–4

- ^ Library of Congress search for Justin Holland

Sources

- Bone, Phillip J. (1914). The Guitar and Mandolin, biographies of celebrated players and composers for these instruments. London: Schott and Co. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- Clemenson, Barbara (2006), Justin Holland, Black Guitarist in the Western Reserve (PDF), Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2014, retrieved August 29, 2014

- Noonan, Jeffrey (2008). The Guitar in America: Victorian Era to Jazz Age. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 61–62. ISBN 9781604733020.

External links

- Barbara Clemenson. Academic paper about Justin Holland.

- Justin Holland's place in American Classical Music

- Biography of Justin Holland in Guitarist, published by the Minnesota Guitar Society. Starts on page 4.

- African heritage in Classical Music, Biography of Justin Holland

- Library of Congress portrait

- Information on Ned Kendall and his brass band

- Aramanth Publishing: bio and downloadable sheet music for Justin Holland

- African-American Registry bio