Josef Ganz

Josef Ganz (1 July 1898 – 26 July 1967) was a Jewish-German car designer born in Budapest, Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Hungary).

Early years

Josef Ganz was born on 1 July 1898 into a Jewish family living in Budapest, then the second-largest city within Austria-Hungary. His mother was Maria Török (1872–1926) from Hungary. His father was Hugo Markus Ganz (1862–1922) from Mainz in Germany who worked as a political and literary writer and journalist for the Frankfurter Zeitung. At an early age, Josef Ganz was fascinated by technology. After moving from Budapest to Vienna, the family moved to Frankfurt am Main in Germany in 1916 and took on German nationality. In July 1916, Ganz voluntarily enlisted in the German army and fought in the German navy during the First World War. After the war, in 1918, Josef Ganz resumed his mechanical engineering studies at the Technische Hochschule Wien. After three semesters, he switched to the Technische Universität Darmstadt.[1][2] He completed his studies in 1927.[1] During this period, he became inspired with the idea of building a small car for the price of a motorcycle.

Prototypes and the Standard Superior

In 1923, as a young mechanical engineering student, Ganz made his first auto sketches for a car for the masses. This was a small lightweight car along the lines of the Rumpler Tropfenwagen with a mid-mounted engine, independent wheel suspension, swing-axles and an aerodynamic body. Lacking the money to build a prototype, he began publishing articles on progressive car design in various magazines and, shortly after his graduation in 1927, he was assigned as the new editor-in-chief of Klein-Motor-Sport. Josef Ganz used this magazine as a platform to criticize heavy, unsafe and old-fashioned cars and promote innovative design and his concept of a car for Germany's general population. The magazine gained in reputation and influence and, in January 1929, was renamed Motor-Kritik. Contributors to the magazine included Béla Barényi, a young engineering student who designed cars with similar design.

Post-war Volkswagen director Heinrich Nordhoff later said "Josef Ganz in Motor-Kritik attacked the old and well-established auto companies with biting irony and with the ardent conviction of a missionary."[3] Companies in turn fought against Motor-Kritik with lawsuits, slander campaigns and an advertising boycott. Publicity for the magazine and Josef Ganz increased.

In 1929, Josef Ganz started contacting German motorcycle manufacturers Zündapp, Ardie and DKW for collaboration to build a prototype, small people's car. This resulted in a first prototype, the Ardie-Ganz, built at Ardie in 1930 and a second one completed at Adler in May 1931, which was nicknamed the Maikäfer (‘May-Beetle’, common European cockchafer Melolontha melolontha). News about the prototypes spread through the industry. At Adler, Josef Ganz was assigned as a consultant engineer at Daimler-Benz and BMW where he was involved in the development of the first models with independent wheel suspension: the Mercedes-Benz 170 and BMW AM1 (Automobilkonstruktion München 1).

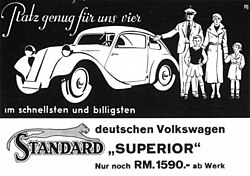

The first company to build a car according to the many patents of Josef Ganz was the Standard Fahrzeugfabrik, which introduced its Standard Superior model at the IAMA (Internationale Auto- und Motorradausstellung) in Berlin in February 1933. It featured a tubular chassis, a mid-mounted engine, and independent wheel suspension with swing-axles at the rear. Here the new Chancellor Adolf Hitler expressed interest in its design and low selling price of 1,590 ℛ︁ℳ︁. Under the new anti-Semitic government, however, Josef Ganz was a target for his enemies from the automotive industry that opposed his writings in Motor-Kritik.

Influence on Porsche

After news about the results achieved with the Ardie-Ganz and Adler Maikäfer prototypes reached Zündapp, the company turned to Ferdinand Porsche in September 1931 to develop an "Auto für Jedermann"—a "car for everyman".[4][5] Porsche already preferred the flat-4 cylinder engine, as was also tried out by Daimler-Benz under supervision of Josef Ganz almost a year previous, but Zündapp preferred a watercooled 5-cylinder radial engine. In 1932, three prototypes were running.[6] All of those cars were lost during the war, the last in a bombing raid over Stuttgart in 1945.

The influence of Ganz on the design of the Volkswagen Beetle is a matter of dispute.[7]

Arrest

Josef Ganz himself was arrested by the Gestapo in May 1933 based on falsified charges of blackmail of the automotive industry. He was eventually released. He fled Germany in June 1934 – the month Adolf Hitler assigned Ferdinand Porsche to design a mass-producible auto for a consumer price of 1,000 Reichsmark.[8]

After a short period in Liechtenstein, Josef Ganz settled in Switzerland where with government support he started a Swiss auto project. In Germany production of the Standard Superior and the Bungartz Butz ended. The first prototypes of the Swiss auto were constructed in 1937 and 1938 and plans were formed for mass-production inside a new factory. After the start of World War II, however, Ganz was again under threat from the Gestapo and Swiss government officials who claimed the Swiss auto project as their own. After the war, a small number of Swiss autos were built by the Rapid car company. Ganz took the Swiss to court.

After five years of court battles, Ganz left Switzerland in 1949 and settled in France. Here he worked on a new small car, but could no longer compete with the Volkswagen.

In 1951 Josef Ganz emigrated to Australia.[9] For some years he worked there for General Motors – Holden, but suffered ill health after a series of heart attacks in the early 1960s.

In 1965 the Federal Republic of Germany sought Australian Government permission to bestow on Josef Ganz the Officer's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. However under regulations existing at that time in relation to foreign awards to Australian citizens, the request was denied.[10]

Josef Ganz died in obscurity in Australia, residing at Edgewater Towers, St Kilda, Melbourne.

Literature

- Paul Schilperoord, The Extraordinary Life of Josef Ganz: The Jewish Engineer Behind Hitler's Volkswagen, RVP Publishers, New York 2011, ISBN 978-1-61412-201-2

References

- ^ a b https://www.tu-darmstadt.de/media/daa_responsives_design/01_die_universitaet_medien/aktuelles_6/publikationen_km/hoch3/pdf/web-hoch3-2017-4.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Josef Ganz erfand den Volkswagen - Ur-Käfer von Frankfurter Ingenieur wird rekonstruiert". bild.de (in German). 28 May 2017. Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ "'A Revelation of a Secret Love'", LIFE International, page 73, October 24, 1960.

- ^ Zündapp, Volkswagen Entwicklung 1932 – Entwurf Porsche, Stuttgart, 5-Zylinder-Sternmotor (PDF) Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zündapp, Volkswagen Entwicklung 1932 (in German), Nürnberg: Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, 2002, p. 20

- ^ TheSamba.com :: Gallery Search

- ^ Jonathan Wood (2003). The Volkswagen Beetle. Osprey Publishing. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-7478-0565-6.

- ^ "Der Fall Ganz: Wie der VW Käfer wirklich entstand", Technology Review (German edition), November 2005. [1]

- ^ Ganz, Josef - Migration and naturalisation, 1951-1968, National Archives of Australia, MP1194/1, V1961/21998 [2]

- ^ Decorations and awards - Germany - Ganz, Josef, National Archives of Australia, A1838, 1535/25/17 [3]

External links

- Joseph Ganz Archive

- Joseph Ganz Foundation

- https://web.archive.org/web/20081016055947/http://www.schouwer-online.de/technik/bungartz.htm

- http://www.bungartz.nl/hist-bungartz.html

- BMW Car Designers Josef Ganz in the overview of automotive designers working for BMW.

- Ganz: How I Lost My Beetle - documentary