Fall of Singapore

| Battle of Singapore | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War of the Second World War | |||||||||

Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival (right), led by Ichiji Sugita, walks under a flag of truce to negotiate the capitulation of Commonwealth forces in Singapore, 15 February 1942. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

85,000 troops 300 guns 1,800+ trucks 200 AFVs 208 anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns 54 fortress guns[a][b] |

36,000 troops 440 artillery pieces[4] 3,000 trucks[5] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

c. c. 80,000 wounded and captured |

1,714 killed 3,378 wounded | ||||||||

The fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,[c] took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Japanese Empire captured the British stronghold of Singapore, with fighting lasting from 8 to 15 February 1942. Singapore was the foremost British military base and economic port in South–East Asia and had been of great importance to British interwar defence strategy. The capture of Singapore resulted in the largest British surrender in history.

Before the battle, Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita had advanced with approximately 30,000 men down the Malayan Peninsula in the Malayan campaign. The British erroneously considered the jungle terrain impassable, leading to a swift Japanese advance as Allied defences were quickly outflanked. The British Lieutenant-General, Arthur Percival, commanded 85,000 Allied troops at Singapore, although many units were under-strength and most units lacked experience. The British outnumbered the Japanese but much of the water for the island was drawn from reservoirs on the mainland. The British destroyed the causeway, forcing the Japanese into an improvised crossing of the Johore Strait. Singapore was considered so important that Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered Percival to fight to the last man.

The Japanese attacked the weakest part of the island defences and established a beachhead on 8 February. Percival had expected a crossing in the north and failed to reinforce the defenders in time. Communication and leadership failures beset the Allies and there were few defensive positions or reserves near the beachhead. The Japanese advance continued and the Allies began to run out of supplies. By 15 February, about a million civilians in the city were crammed into the remaining area held by Allied forces, 1 percent of the island. Japanese aircraft continuously bombed the civilian water supply which was expected to fail within days. The Japanese were also almost at the end of their supplies and Yamashita wanted to avoid costly house-to-house fighting.

For the second time since the battle began, Yamashita demanded unconditional surrender and on the afternoon of 15 February, Percival capitulated. About 80,000 British, Indian, Australian and local troops became prisoners of war, joining the 50,000 taken in Malaya; many died of neglect, abuse or forced labour. Three days after the British surrender, the Japanese began the Sook Ching purge, killing thousands of civilians. The Japanese held Singapore until the end of the war. About 40,000, mostly conscripted, Indian soldiers joined the Indian National Army and fought with the Japanese in the Burma campaign. Churchill called it the worst disaster in British military history. The fall of Singapore, the sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse, and other defeats in 1941–42 all severely undermined British prestige, which contributed to the end of British colonial rule in the region after the war.

Background

Outbreak of war

In the interwar years, Britain had established a naval base in Singapore after the Anglo-Japanese alliance had lapsed in 1923. As part of the Singapore strategy, the base formed a key part of British interwar defence planning for the region. Financial constraints had hampered construction efforts during the intervening period and shifting strategic circumstances had largely undermined the key premises behind the strategy by the time war had broken out in the Pacific.[6][7] During 1940 and 1941, the Allies imposed a trade embargo on Japan in response to its campaigns in China and its occupation of French Indochina.[8][9] The basic plan for taking Singapore was worked out in July 1940. Intelligence gained in late 1940–early 1941 did not alter that plan but confirmed it in the minds of Japanese decision makers.[10] On 11 November 1940, the German raider Atlantis captured the British steamer Automedon in the Indian Ocean, carrying papers meant for Air Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, the British commander in the Far East. The papers included information about the weakness of the Singapore base. In December 1940, the Germans handed over copies of the papers to the Japanese. The Japanese had broken the British Army's codes and in January 1941, the Second Department (the intelligence-gathering arm) of the Imperial Army interpreted and read a message from Singapore to London complaining in much detail about the weak state of "Fortress Singapore", a message so frank in its admission of weakness that the Japanese at first suspected it was a British plant, believing that no officer would be so open in admitting weaknesses to his superiors. Only after cross-checking the message with the Automedon papers did the Japanese accept it to be genuine.[11]

Japanese oil reserves were rapidly being depleted because of its military operations in China and by industrial consumption. In the latter half of 1941, the Japanese began preparations for war to seize vital resources if peaceful efforts to buy them failed. Planners determined a broad scheme of manoeuvres that incorporated simultaneous attacks on the territories of Britain, The Netherlands and the United States. This would see landings in Malaya and Hong Kong as part of a general move south to secure Singapore, connected to Malaya by the Johor–Singapore Causeway and then an invasion of the oil-rich area of Borneo and Java in the Dutch East Indies. Attacks would be made against the American naval fleet at Pearl Harbor as well as landings in the Philippines and attacks on Guam, Wake Island and the Gilbert Islands.[12][13] Following these attacks, a period of consolidation was planned, after which the Japanese planners intended to build up the defences of the captured territory by establishing a strong perimeter from the India–Burma frontier through to Wake Island and traversing Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, New Guinea and New Britain, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. This perimeter would be used to block Allied attempts to regain the lost territory and defeat their will to fight.[12]

Invasion of Malaya

The Japanese 25th Army invaded Malaya from Indochina, moving into northern Malaya and Thailand by amphibious assault on 8 December 1941.[14][15] This was virtually simultaneous with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor which precipitated the United States' entry into the war. Thailand resisted landings on its territory for about 5 to 8 hours; it then signed a ceasefire and a Treaty of Friendship with Japan, later declaring war on the UK and the US. The Japanese then proceeded overland across the Thai–Malayan border to attack Malaya. At this time, the Japanese began bombing Singapore.[16]

The 25th Army was resisted in northern Malaya by III Corps of the British Indian Army. Although the 25th Army was outnumbered by Commonwealth forces in Malaya and Singapore, they did not take the initiative with their forces while Japanese commanders concentrated theirs. The Japanese were superior in close air support, armour, co-ordination, tactics and experience. Conventional British military thinking was that the Japanese forces were inferior and characterised the Malayan jungles as "impassable"; the Japanese were repeatedly able to use this to their advantage to outflank hastily established defensive lines.[17][18] Prior to the Battle of Singapore the most resistance was met at the Battle of Muar which involved the 8th Australian Division and the 45th Indian Brigade. The British troops left in the city of Singapore were basically garrison troops.[19][20]

At the start of the campaign, the Commonwealth forces had only 164 first-line aircraft in Malaya and Singapore and the only fighter type was the sub-standard Brewster 339E Buffalo. The Buffaloes were operated by one Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), two Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), and two Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons.[21] The aircraft were, according to historian Peter Dennis, "not considered good enough for use in Europe" and major shortcomings included a slow rate of climb and the fuel system, which required the pilot to hand-pump fuel if flying above 6,000 ft (1,800 m).[22] The Imperial Japanese Army Air Force was more numerous and better trained than the second-hand assortment of untrained pilots and inferior Commonwealth equipment remaining in Malaya, Borneo and Singapore. Japanese fighters were superior to the Commonwealth fighters, which helped the Japanese to gain air supremacy.[23] Although outnumbered and outclassed, the Buffalos were able to provide some resistance, with RAAF pilots alone managing to shoot down at least 20 Japanese aircraft before the few survivors were withdrawn.[22]

Force Z, consisting of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, the battlecruiser HMS Repulse and four destroyers, sailed north out of Singapore on 8 December to oppose expected Japanese landings along the coast of Malaya. Japanese land-based aircraft found and sank the two capital ships on 10 December,[24] leaving the east coast of the Malayan Peninsula exposed and allowing the Japanese to continue their amphibious landings. Japanese forces quickly isolated, surrounded and forced the surrender of Indian units defending the coast. Despite their numerical inferiority, they advanced down the Malayan Peninsula, overwhelming the defences. The Japanese forces also used bicycle infantry and light tanks, allowing swift movement through the jungle. The Commonwealth having thought the terrain made them impractical, had no tanks and only a few armoured vehicles, which put them at a severe disadvantage.[25]

Although more Commonwealth units—including some from the 8th Australian Division—joined the campaign, the Japanese prevented them from regrouping.[d] The Japanese overran cities and advanced toward Singapore, which was an anchor for the operations of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), the first Allied joint command of the Second World War. Singapore controlled the main shipping channel between the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. An ambush was sprung by the 2/30th Australian Battalion on the main road at the Gemenceh River near Gemas on 14 January, causing many Japanese casualties.[27][e]

At Bakri, from 18 to 22 January, the Australian 2/19th and 2/29th battalions and the 45th Indian Brigade (Lieutenant Colonel Charles Anderson) repeatedly fought through Japanese positions before running out of ammunition near Parit Sulong. The survivors were forced to leave behind about 110 Australian and 40 Indian wounded, who were later beaten, tortured and murdered by Japanese troops during the Parit Sulong Massacre.[29] Of over 3,000 men from these units only around 500 men escaped. For his leadership in the fighting withdrawal, Anderson was awarded the Victoria Cross.[30][31] A determined counter-attack by the 5/11th Sikh Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel John Parkin) in the area of Niyor, near Kluang, on 25 January and an ambush around the Nithsdale Estate by the 2/18th Australian Battalion on 26/27 January bought valuable time and permitted East Force, based on the 22nd Australian Brigade (Brigadier Harold Taylor), to withdraw from eastern Johor (formerly Johore).[32][33][34] On 31 January, the last Commonwealth forces crossed the causeway linking Johor and Singapore and engineers blew it up.[35][36]

Prelude

During the weeks preceding the invasion, Commonwealth forces suffered a number of both subdued and openly disruptive disagreements amongst its senior commanders,[37] as well as pressure from Australian Prime Minister John Curtin.[38] Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, commander of the garrison, had 85,000 soldiers—the equivalent, on paper at least, of just over four divisions.[39][f] Of this figure, 15,000 men were employed in supply, administrative, or other non-combatant roles. The remaining force was a mix of front-line and second-line troops. There were 49 infantry battalions—21 Indian, 13 British, six Australian, four Indian States Forces assigned to airfield defence, three Straits Settlements Volunteer Force, and two Malayan. In addition, there were two British machine-gun battalions, one Australian, and a British reconnaissance battalion.[41] The newly arrived 18th Infantry Division (Major-General Merton Beckwith-Smith)[42][43]—was at full strength but lacked experience and training.[44] The rest of the force was of mixed quality, condition, training, equipment and morale. Lionel Wigmore, the Australian official historian of the Malayan campaign, wrote

Only one of the Indian battalions was up to numerical strength, three (in the 44th Brigade) had recently arrived in a semi-trained condition, nine had been hastily reorganised with a large intake of raw recruits, and four were being re-formed but were far from being fit for action. Six of the United Kingdom battalions (in the 54th and 55th Brigades of the British 18th Infantry Division) had only just landed in Malaya, and the other seven battalions were under-manned. Of the Australian battalions, three had drawn heavily upon undertrained recruits, new to the theatre. The Malay battalions had not been in action, and the Straits Settlements Volunteers were only sketchily trained. Further, losses on the mainland had resulted in a general shortage of equipment.[43]

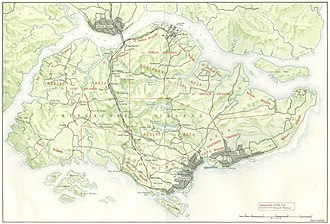

Percival gave Major-General Gordon Bennett's two brigades from the 8th Australian Division responsibility for the western side of Singapore, including the prime invasion points in the northwest of the island. This was mostly mangrove swamp and jungle, broken by rivers and creeks.[45] In the heart of the "Western Area" was RAF Tengah, Singapore's largest airfield at the time. The Australian 22nd Brigade, under Brigadier Harold Taylor, was assigned a 10 mi (16 km) wide sector in the west, and the 27th Brigade, under Brigadier Duncan Maxwell, had responsibility for a 4,000 yd (3,700 m) zone just west of the Causeway. The infantry positions were reinforced by the recently arrived Australian 2/4th Machine-Gun Battalion.[46] Also under Bennett's command was the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade.[45]

The III Indian Corps (Lieutenant-General Sir Lewis Heath) including the 11th Indian Infantry Division under Major-General Berthold Key with reinforcements from the 8th Indian Brigade,[47] and the 18th Infantry Division—was assigned the north-eastern sector, known as the "Northern Area".[45] This included the naval base at Sembawang. The "Southern Area", including the main urban areas in the south-east, was commanded by Major-General Frank Simmons. His forces consisted of elements of the 1st Malaya Infantry Brigade and the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force Brigade with the Indian 12th Infantry Brigade in reserve.[48]

From 3 February, the Commonwealth forces were shelled by Japanese artillery, and air attacks on Singapore intensified over the next five days. The artillery and air bombardment strengthened, severely disrupting communications between Commonwealth units and their commanders and affecting preparations for the defence of the island.[49] From aerial reconnaissance, scouts, infiltrators and observation from high ground across the straits (such as at Istana Bukit Serene and the Sultan of Johor's palace), Japanese commander General Tomoyuki Yamashita and his staff gained excellent knowledge of the Commonwealth positions. Yamashita and his officers stationed themselves at Istana Bukit Serene and the Johor state secretariat building—the Sultan Ibrahim Building—to plan for the invasion of Singapore.[50][51] Although his military advisors judged that Istana Bukit Serene was an easy target, Yamashita was confident that the British Army would not attack the palace because it belonged to the Sultan of Johor. Yamashita's prediction was correct; despite being observed by Australian artillery, permission to engage the palace was denied by Gordon Bennett.[52]

Most of Singapore's BL 15-inch Mk I naval guns could be traversed north and were used to engage the Japanese. The guns—which included the Johore Battery, with three 15 in (380 mm) guns and one battery with two 15 in (380 mm) guns—were supplied mostly with armour-piercing shells (AP) for anti-shipping use and few high explosive (HE) shells.[53][54][g] Percival incorrectly guessed that the Japanese would land forces on the north-east side of Singapore, ignoring advice that the north-west was a more likely direction of attack (where the Straits of Johor were the narrowest and a series of river mouths provided cover for the launching of water craft).[56] This was encouraged by the deliberate movement of Japanese troops in this sector to deceive the British.[57] Much of the equipment and resources of the garrison had been incorrectly allocated to the north east sector, where the most complete and freshest formation—the 18th Infantry Division—was deployed, while the depleted 8th Australian Division sector with two of its three brigades had no serious fixed defensive works or obstacles. To compound matters, Percival had ordered the Australians to defend forward so as to cover the waterway, yet this meant they were immediately fully committed to any fighting, limiting their flexibility, whilst also reducing their defensive depth.[56] The two Australian brigades were subsequently allocated a very wide frontage of over 11 mi (18 km) and were separated by the Kranji River.[58]

Yamashita had just over 30,000 men from three divisions: the Imperial Guards Division (Lieutenant-General Takuma Nishimura), the 5th Division (Lieutenant-General Takuro Matsui) and the Japanese 18th Division (Lieutenant-General Renya Mutaguchi).[59] Also in support was a light tank brigade.[60] In comparison, following the withdrawal, Percival had about 85,000 men at his disposal, although 15,000 were administrative personnel, while large numbers were semi-trained British, Indian and Australian reinforcements that had only recently arrived. Of those forces that had seen action during the previous fighting, the majority were under-strength and under-equipped.[61]

In the days leading up to the Japanese attack, patrols from the Australian 22nd Brigade were sent across the Straits of Johor at night to gather intelligence. Three small patrols were sent on the evening of 6 February, one was spotted and withdrew after its leader was killed and their boat sunk and the other two managed to get ashore. Over the course of a day, they found large concentrations of troops, although they were unable to locate any landing craft.[62] The Australians requested the shelling of these positions to disrupt the Japanese preparations but the patrol reports were later ignored by Malaya Command as being insignificant, based upon the belief that the real assault would come in the north-eastern sector, not the north-west.[63][64]

Battle

Japanese landings

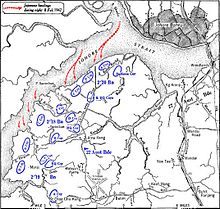

Blowing up the causeway had delayed the Japanese attack for over a week. Prior to the main assault, the Australians were subjected to an intense artillery bombardment. Over a period of 15 hours, starting at 23:00 on 8 February 1942, Yamashita's heavy guns fired a bombardment of 88,000 shells (200 rounds per gun) along the straits, cutting telephone lines and isolating forward units.[58][4][65] The British had the means to conduct counter-battery fire opposite the Australians that would have caused casualties and disruption among the Japanese assault troops.[66] The bombardment of the Australians was not seen as a prelude to attack—Malaya Command believed that it would last several days and would later switch its focus to the north-east, despite its ferocity exceeding anything the Allies had experienced thus far in the campaign; no order was passed to the Commonwealth artillery units to bombard possible Japanese assembly areas.[67]

Shortly before 20:30 on 8 February, the first wave of Japanese troops from the 5th Division and 18th Division began crossing the Johor Strait. The main weight of the Japanese force, about 13,000 men, from 16 assault battalions, with five in reserve, attacked the 22nd Australian Brigade.[68] The assault was received by the 2/18th Battalion and the 2/20th Battalion. Each Japanese division had 150 barges and collapsible boats, sufficient for lifts of 4,000. During the first night 13,000 Japanese troops landed and were followed by another 10,000 after first light.[69] The Australians numbered just 3,000 men and lacked any significant reserve.[58]

As the landing craft closed on the Australian positions, machine gunners from the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, interspersed amongst the rifle companies, opened fire. Spotlights had been placed on the beaches by a British unit to illuminate an invasion force on the water but many had been damaged by the bombardment and no order was made to turn the others on. The initial wave was concentrated against the positions occupied by the 2/18th and 2/20th Battalions, around the Buloh River, as well as one company from the 2/19th Battalion. Over the course of an hour, intense fighting took place on the right flank of the 2/19th Battalion, until its positions were overrun, the Japanese then advanced inland concealed by the darkness and the vegetation. The resistance put up by the company from the 2/19th pushed the follow-on waves of Japanese craft to land around the mouth of Murai River, which resulted in them creating a gap between the 2/19th and 2/18th battalions. From there the Japanese launched two concerted attacks against the 2/18th, which were met with massed fire before they overwhelmed the Australians by weight of numbers. Urgent requests for fire support were made and the 2/15th Field Regiment responded to these requests with over 4,800 rounds.[70]

Fierce fighting raged throughout the evening but due to the terrain and the darkness, the Japanese were able to disperse into the undergrowth, surround and overwhelm pockets of Australian resistance or bypass them exploiting gaps in the thinly spread Commonwealth lines due to the many rivers and creeks in the area. By midnight, the two Japanese divisions fired star shell to indicate to their commander that they had secured their initial objectives and by 01:00 they were well established. Over the course of two hours, the three Australian battalions that had been engaged sought to regroup, moving back east from the coast towards the centre of the island, which was completed mainly in good order. The 2/20th managed to concentrate three of its four companies around the Namazie Estate, although one was left behind; the 2/18th was only able to concentrate half its strength at Ama Keng, while the 2/19th also moved back three companies, leaving a fourth to defend Tengah airfield. Further fighting followed in the early morning of 9 February and the Australians were pushed back further, with the 2/18th being pushed out of Ama Keng and the 2/20th being forced to pull back to Bulim, west of Bukit Panjong. Bypassed elements tried to break out and fall back to the Tengah airfield to rejoin their units and suffered many casualties. Bennett attempted to reinforce the 22nd Brigade by moving the 2/29th Battalion from the 27th Brigade area to Tengah but before it could be used to recapture Ama Keng, the Japanese launched another attack around the airfield and the 2/29th was forced onto the defensive.[71] The initial fighting cost the Australians many casualties, with the 2/20th alone losing 334 men killed and 214 wounded.[72]

Air operations

The air campaign for Singapore began during the invasion of Malaya. Early on 8 December 1941, Singapore was bombed for the first time by long-range Japanese aircraft, such as the Mitsubishi G3M2 "Nell" and the Mitsubishi G4M1 "Betty", based in Japanese-occupied Indochina. The bombers struck the city centre as well as the Sembawang Naval Base and the northern airfields. For the rest of December there were false alerts and several infrequent and sporadic hit-and-run attacks on outlying military installations such as the Naval Base but no raids on Singapore City. The situation had become so desperate that one British soldier took to the middle of a road to fire his Vickers machine gun at any aircraft that passed. He could only say "The bloody bastards will never think of looking for me in the open, and I want to see a bloody plane brought down".[73] The next recorded raid on the city occurred on the night of 29/30 December, and nightly raids ensued for over a week, accompanied by daylight raids from 12 January 1942.[74] As the Japanese army advanced towards Singapore Island, the day and night raids increased in frequency and intensity, resulting in thousands of civilian casualties, up to the time of the British surrender.[75]

In December, 51 Hawker Hurricane Mk II fighters and 24 pilots were sent to Singapore, the nuclei of five squadrons. They arrived on 3 January 1942, by which stage the Buffalo squadrons had been overwhelmed. No. 232 Squadron RAF was formed and No. 488 Squadron RNZAF, a Buffalo squadron, had converted to Hurricanes; 232 Squadron became operational on 20 January and destroyed three Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscars" that day, for the loss of three Hurricanes. Like the Buffalos the Hurricanes began to suffer severe losses in dogfights.[76][h] From 27 to 30 January, another 48 Hurricanes arrived on the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable.[77] Operated by the four squadrons of No. 226 Group RAF, they flew from an airfield code-named P1, near Palembang, Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies, while a flight was maintained in Singapore.[78] Many of the Hurricanes were destroyed on the ground by air raids.[79] The lack of an effective air early warning system throughout the campaign meant that many Commonwealth aircraft were lost in this manner during Japanese attacks against airfields.[80]

By the time of the invasion, only ten Hurricanes of 232 Squadron, based at RAF Kallang, remained to provide air cover for the Commonwealth forces on Singapore. The airfields at Tengah, Seletar and Sembawang were in range of Japanese artillery at Johor Bahru. RAF Kallang was the only operational airstrip left; the surviving squadrons and aircraft had withdrawn by January to reinforce the Dutch East Indies.[81] On the morning of 9 February, dogfights took place over Sarimbun Beach and other western areas. In the first encounter, the last ten Hurricanes were scrambled from Kallang Airfield to intercept a Japanese formation of about 84 aircraft, flying from Johor to provide air cover for their invasion force.[82] The Hurricanes shot down six Japanese aircraft and damaged 14 others for the loss of a Hurricane.[83]

Air battles went on for the rest of the day and by nightfall it was clear that with the few aircraft Percival had left, Kallang could no longer be used as a base. With his assent, the remaining flyable Hurricanes were withdrawn to Sumatra.[84] A squadron of Hurricane fighters took to the skies on 9 February but was then withdrawn to the Netherlands East Indies and after that no Commonwealth aircraft were seen again over Singapore; the Japanese had achieved air supremacy.[85][86] That evening, three Fairmile B motor launches attacked and sank several Japanese landing craft in the Johor Strait around its western channel on the evening of 9 February.[85] On the evening of 10 February, General Archibald Wavell, commander of ABDA, ordered the transfer of all remaining Commonwealth air force personnel to the Dutch East Indies. By this time, Kallang Airfield was, according to author Frank Owen, "so pitted with bomb craters that it was no longer usable".[87]

Second day

Believing that further landings would occur in the northeast, Percival did not reinforce the 22nd Brigade until the morning of 9 February, sending two half-strength battalions from the 12th Indian Infantry Brigade. The Indians reached Bennett around noon. Shortly afterwards Percival allocated the composite 6th/15th Indian Infantry Brigade to reinforce the Australians from their position around the Singapore racecourse.[88] Throughout the day, the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade, still holding its position on the coast, began to feel pressure on its exposed flank and after discussions between Percival and Bennett, it was decided that they would have to retire eastwards to maintain the southern part of the Commonwealth line.[89] Bennett decided to form a secondary defensive line, known as the "Kranji-Jurong Switch Line" facing west between the two rivers, with its centre around Bulim, east of Tengah Airfield—which subsequently came under Japanese control—and just north of Jurong.[90][89]

To the north, the 27th Australian Brigade had not been engaged during the Japanese assaults on the first day. Possessing only the 2/26th and 2/30th, following the transfer of the 2/29th Battalion to the 22nd Brigade, Maxwell sought to reorganise his force to deal with the threat posed to the western flank.[91] Late on 9 February, the Imperial Guards began assaulting the positions held by the 27th Brigade, concentrating on those held by the 2/26th Battalion.[92] During the initial assault, the Japanese suffered severe casualties from Australian mortars and machine-guns and from burning oil which had been sluiced into the water following the demolition of several oil tanks by the Australians.[93] Some of the Guards reached the shore and maintained a tenuous beachhead; at the height of the assault, it is reported that the Guards commander, Nishimura, requested permission to cancel the attack due to the many casualties his troops had suffered from the fire but Yamashita ordered them to press on.[94]

Communication problems caused further cracks in the Commonwealth defence. Maxwell knew that the 22nd Brigade was under increasing pressure but was unable to contact Taylor and was wary of encirclement.[95] As parties of Japanese troops began to infiltrate the brigade's positions from the west, exploiting the gap formed by the Kranji River, the 2/26th Battalion was forced to withdraw to a position east of the Bukit Timah Road; this move precipitated a sympathetic move by the 2/30th away from the causeway.[90] The authority for this withdrawal would later be the subject of debate, with Bennett stating that he had not given Maxwell authorisation to do so.[95] The result was that the Allies lost control of the beaches adjoining the west side of the causeway, the high ground overlooking the causeway and the left flank of the 11th Indian Division was exposed.[96] The Japanese were given a firm foothold to "build up their force unopposed".[85]

Japanese breakthrough

The opening at Kranji made it possible for Imperial Guards armoured units to land there unopposed, after which they were able to begin ferrying across their artillery and armour.[97][66] After finding his left flank exposed by the withdrawal of the 27th Brigade, the commander of the 11th Indian Infantry Division, Key, dispatched the 8th Indian Infantry Brigade from reserve, to retake the high ground to the south of the Causeway.[98] Throughout 10 February further fighting took place around along the Jurong Line, as orders were formulated to establish a secondary defensive line to the west of the Reformatory Road, with troops not then employed in the Jurong Line; misinterpretation of these orders resulted in Taylor, the commander of the 22nd Brigade, prematurely withdrawing his troops to the east, where they were joined by a 200-strong ad hoc battalion of Australian reinforcements, known as X Battalion. The Jurong Line eventually collapsed after the 12th Indian Brigade was withdrawn by its commander, Brigadier Archie Paris, to the road junction near Bukit Panjang, after he lost contact with the 27th Brigade on his right; the commander of the 44th Indian Brigade, Ballantine, commanding the extreme left of the line, also misinterpreted the orders in the same manner that Taylor had and withdrew.[99] On the evening of 10 February, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, cabled Wavell

I think you ought to realise the way we view the situation in Singapore. It was reported to Cabinet by the CIGS [Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Alan Brooke] that Percival has over 100,000 [sic] men, of whom 33,000 are British and 17,000 Australian. It is doubtful whether the Japanese have as many in the whole Malay Peninsula ... In these circumstances the defenders must greatly outnumber Japanese forces who have crossed the straits, and in a well-contested battle they should destroy them. There must at this stage be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population. The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs. The 18th Division has a chance to make its name in history. Commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and of the British Army is at stake. I rely on you to show no mercy to weakness in any form. With the Russians fighting as they are and the Americans so stubborn at Luzon, the whole reputation of our country and our race is involved. It is expected that every unit will be brought into close contact with the enemy and fight it out.[100]

In the early afternoon of 10 February, on learning of the collapse of the Jurong Line, Wavell ordered Percival to launch a counter-attack to retake it.[101] This order was passed on to Bennett, who allocated X Battalion. Percival made plans of his own for the counter-attack, detailing a three-phased operation that involved the majority of the 22nd Brigade, and he subsequently passed this on to Bennett, who began implementing the plan, but forgot to call X Battalion back. The battalion, consisting of poorly trained and equipped replacements, advanced to an assembly area near Bukit Timah.[102] In the early hours of 11 February, the Japanese, who had concentrated significant forces around the Tengah airfield and on the Jurong Road, began further offensive operations: the 5th Division aimed its advance towards Bukit Panjang, while the 18th Division struck out towards Bukit Timah. They fell upon X Battalion, which had camped in its assembly area while waiting to launch its counter-attack, and two-thirds of the battalion was killed or wounded.[103] After brushing aside elements of the 6th/15th Indian Brigade, the Japanese again began attacking the 22nd Australian Brigade around the Reformatory Road.[104]

Later on 11 February, with Japanese supplies running low, Yamashita attempted to bluff Percival, calling on him to "give up this meaningless and desperate resistance".[105][106] The fighting strength of the 22nd Brigade—which had borne the brunt of the Japanese attacks—had been reduced to a few hundred men and the Japanese had captured the Bukit Timah area, including the main food and fuel depots of the garrison.[107] Wavell told Percival that the garrison was to fight on to the end and that there should not be a general surrender in Singapore.[108][109][110] With the vital water supply of the reservoirs in the centre of the island threatened, the 27th Australian Brigade was later ordered to recapture Bukit Panjang as a preliminary move in retaking Bukit Timah.[111] The counter-attack was repulsed by the Imperial Guards and the 27th Australian Brigade was split in half on either side of the Bukit Timah Road with elements spread as far as the Pierce Reservoir.[112]

My attack on Singapore was a bluff—a bluff that worked. I had 30,000 men and was outnumbered more than three to one. I knew that if I had to fight for long for Singapore, I would be beaten. That is why the surrender had to be at once. I was very frightened all the time that the British would discover our numerical weakness and lack of supplies and force me into disastrous street fighting.

The next day, as the situation worsened for the Commonwealth, they sought to consolidate their defences; during the night of 12/13 February, the order was given for a 28 mi (45 km) perimeter to be established around Singapore City at the eastern end of the island. This was achieved by moving the defending forces from the beaches along the northern shore and from around Changi, with the 18th Infantry Division being tasked to maintain control of the vital reservoirs and effecting a link up with Simmons' Southern Area forces.[114] The withdrawing troops received harassing attacks all the way back.[115] Elsewhere, the 22nd Brigade continued to hold a position west of the Holland Road until late in the evening when it was pulled back to Holland Village.[116]

On 13 February, Japanese engineers repaired the road over the causeway and more tanks were pushed across.[117] With the Commonwealth still losing ground, senior officers advised Percival to surrender in the interest of minimising civilian casualties. Percival refused but tried to get authority from Wavell for greater discretion as to when resistance might cease.[118][119] The Japanese captured the water reservoirs that supplied the town but did not cut off the supply.[120] That day, military police executed Captain Patrick Heenan for espionage.[121] An Air Liaison Officer with the British Indian Army, Heenan had been recruited by Japanese military intelligence and had used a radio to assist them in attacking Commonwealth airfields in northern Malaya. He had been arrested on 10 December and court-martialled in January. Heenan was shot at Keppel Harbour, on the southern side of Singapore and his body was thrown into the sea.[122][123]

The Australians occupied a perimeter of their own to the north-west around Tanglin Barracks, in which they maintained an all round defence as a precaution. To their right, the 18th Division, the 11th Indian Division and the 2nd Malaya Brigade held the perimeter from the edge of the Farrar Road east to Kallang, while to their left, the 44th Indian Brigade and the 1st Malaya Brigade held the perimeter from Buona Vista to Pasir Panjang.[124] For the most part, there was limited fighting around the perimeter, except around Pasir Panjang Ridge, 1 mi (1.6 km) from Singapore Harbour, where the 1st Malaya Brigade—which consisted of a Malayan infantry battalion, two British infantry battalions and a force of Royal Engineers—fought a stubborn defensive action during the Battle of Pasir Panjang.[124][125] The Japanese largely avoided attacking the Australian perimeter but in the northern area, the British 53rd Infantry Brigade was pushed back by a Japanese assault up the Thompson Road and had to fall back north of Braddell Road in the evening, joining the rest of the 18th Infantry Division in the line. They dug in and throughout the night fierce fighting raged on the northern front.[126]

The following day, the remaining Commonwealth units fought on. Civilian casualties mounted as a million people crowded into the 3 mi (4.8 km) area still held by the Commonwealth and bombing and artillery-fire increased.[127] The civilian authorities began to fear that the water supply would give out; Percival was advised that large amounts of water were being lost due to damaged pipes and that the water supply was on the verge of collapse.[128][i]

Alexandra Hospital massacre

On 14 February 1942, the Japanese renewed their assault on the western part of the Southern Area's defences near the area that the 1st Malayan Brigade had fought desperately to hold the previous day.[129][117] At about 13:00, the Japanese broke through and advanced towards the Alexandra Barracks Hospital. A British lieutenant—acting as an envoy with a white flag—approached Japanese forces but was killed with a bayonet.[130] After Japanese troops entered the hospital, they killed up to 50 soldiers, including some undergoing surgery. Doctors and nurses were also killed.[131] The next day, about 200 male staff members and patients who had been assembled and bound the previous day,[131] many of them walking wounded, were ordered to walk about 400 m (440 yd) to an industrial area. Those who fell on the way were bayoneted. The men were forced into a series of small, badly ventilated rooms where they were held overnight without water. Some died during the night as a result of their treatment.[131] The remainder were bayoneted the following morning.[132][133] Several survivors were identified after the war, some of whom had survived by pretending to be dead. One survivor, Private Arthur Haines from the Wiltshire Regiment, wrote a four-page account of the massacre that was sold by his daughter by private auction in 2008.[134]

Fall of Singapore

Throughout the night of 14/15 February, the Japanese continued to press against the Commonwealth perimeter, and though the line largely held, the military supply situation was rapidly deteriorating. The water system was badly damaged and supply was uncertain, rations were running low, petrol for military vehicles was all but exhausted, and there was little ammunition left for the field artillery and anti-aircraft guns, which were unable to disrupt the Japanese air attacks causing many casualties in the city centre.[135] Little work had been done to build air raid shelters, and looting and desertion by Commonwealth troops further added to the chaos in the area.[136][j] At 09:30, Percival held a conference at Fort Canning with his senior commanders. He proposed two options: an immediate counter-attack to regain the reservoirs and the military food depots around Bukit Timah, or surrender. After a full and frank exchange of views, all present agreed that no counter-attack was possible, and Percival opted for surrender.[139][135] Post-war analysis has shown that a counter-attack might have succeeded. The Japanese were at the limit of their supply line and their artillery units were also running out of ammunition.[140]

A delegation was selected to go to the Japanese headquarters. It consisted of a senior staff officer, the colonial secretary and an interpreter. The three set off in a motor car bearing a Union Jack and a white flag of truce toward the enemy lines to discuss a cessation of hostilities.[141] They returned with orders that Percival himself proceed with staff officers to the Ford Motor Factory, where Yamashita would lay down the terms of surrender. A further requirement was that the Japanese Rising Sun Flag be hoisted over the Cathay Building, the tallest building in Singapore.[142] Percival formally surrendered shortly after 17:15.[120] Earlier that day, Percival had issued orders to destroy all secret and technical equipment, ciphers, codes, secret documents and heavy guns.[143]

Under the terms of the surrender, hostilities were to cease at 20:30 that evening, all military forces in Singapore were to surrender unconditionally, all Commonwealth forces would remain in position and disarm themselves within an hour, and the British were allowed to maintain a force of 1,000 armed men to prevent looting until relieved by the Japanese. Yamashita also accepted full responsibility for the lives of the civilians in the city.[144] Following the surrender, Bennett caused controversy when he decided to escape. After receiving news of the surrender, Bennett handed command of the 8th Australian Division to the divisional artillery commander, Brigadier Cecil Callaghan and—along with some of his staff officers—commandeered a small boat.[145]

Bennett's party eventually made its way back to Australia while between 15,000 and 20,000 Australian soldiers were reportedly captured.[146][147][148] Bennett blamed Percival and the Indian troops for the defeat but Callaghan reluctantly stated that Australian units had been affected, towards the end of the battle, by many desertions.[k][l] The Kappe Report, compiled by Colonels J. H. Thyer and C. H. Kappe, concedes that at most only two-thirds of the Australian troops manned the final perimeter.[149] Many British units were reported to have been similarly affected.[138]

In analysing the campaign, Clifford Kinvig, a senior lecturer at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, blamed the commander of the 27th Infantry Brigade, Brigadier Duncan Maxwell, for his defeatist attitude and not properly defending the sector between the Causeway and the Kranji River.[151][137] Elphick also claims that Australians made up the majority of stragglers.[152] According to another source, Taylor cracked under the pressure.[m] Thompson wrote that the 22nd Australian Brigade was "so heavily outnumbered that defeat was inevitable" and Costello states that Percival's insistence on concentrating the 22nd Australian Brigade at the water's edge had been a serious mistake.[153][136] Yamashita, the Japanese commander, laid the blame on the British "underestimating Japanese military capabilities" and Percival's hesitancy in reinforcing the Australians on the western side of the island.[154]

A classified wartime report by Wavell released in 1992 blamed the Australians for the loss of Singapore.[28] According to John Coates, the report "lacked substance", for though there had undoubtedly been a lack of discipline in the final stages of the campaign—particularly among the poorly trained British, Indian and Australian reinforcements that were hurriedly dispatched as the crisis worsened—the 8th Australian Division had fought well and had gained the respect of the Japanese.[155] At Gemas, Bakri and Jemaluang, "they achieved the few outstanding tactical successes" of the campaign in Malaya and although the Australians made up 13 per cent of the British Empire's ground forces, they suffered 73 per cent of its battle deaths.[156][148] Coates argues that the real reason for the fall of Singapore was the failure of the Singapore strategy, to which Australian policy-makers had contributed in their acquiescence and the lack of military resources allocated to the fighting in Malaya.[155]

Aftermath

Analysis

The Japanese had advanced 650 mi (1,050 km) from Singora, Thailand, to the southern coast of Singapore at an average rate of 9 mi (14 km) a day.[157] While impressed with Japan's quick succession of victories, Adolf Hitler reportedly forbade Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop from issuing a congratulatory communique.[158] Churchill called the fall of Singapore to the Japanese "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history".[159] Churchill's physician Lord Moran wrote:

The fall of Singapore on February 15 stupefied the Prime Minister. How came 100,000 men (half of them of our own race) to hold up their hands to inferior numbers of Japanese? Though his mind had been gradually prepared for its fall, the surrender of the fortress stunned him. He felt it was a disgrace. It left a scar on his mind. One evening, months later, when he was sitting in his bathroom enveloped in a towel, he stopped drying himself and gloomily surveyed the floor: 'I cannot get over Singapore', he said sadly.[160]

The loss of Singapore, along with other defeats in Southeast Asia in 1942, reduced British prestige in the region. According to author Alan Warren, the Fall of Singapore shattered "the British Empire's illusion of permanence ... and strength", ultimately making "European empires in Asia unsustainable beyond the short term" and presaging the end of colonialism in the region in the post war period.[161]

Casualties

Nearly 85,000 British, Indian and Commonwealth troops were captured, in addition to losses during the earlier fighting in Malaya.[157] About 5,000 men were killed or wounded, a majority of whom were Australian.[162][163] Japanese casualties during the fighting in Singapore amounted to 1,714 killed and 3,378 wounded. During the 70-day campaign in Malaya and Singapore, total Commonwealth casualties amounted to 8,708 killed or wounded and 130,000 captured (38,496 United Kingdom, 18,490 Australian of whom 1,789 were killed and 1,306 wounded, 67,340 Indian and 14,382 local volunteer troops), against 9,824 Japanese casualties.[157]

Subsequent events

The Japanese occupation of Singapore started after the British surrender. Japanese newspapers triumphantly declared the victory as deciding the general situation of the war.[164] The city was renamed Syonan-to (昭南島 Shōnan-tō; literally: 'Southern Island gained in the age of Shōwa', or 'Light of the South').[165][166] Curtin compared the loss of Singapore to the Battle of Dunkirk. The Battle of Britain occurred after Dunkirk; "the fall of Singapore opens the Battle for Australia", Curtin said, which threatened the Commonwealth, the United States, and the entire English-speaking world.[167]

The Japanese sought vengeance against the Chinese and anyone who held anti-Japanese sentiments. The Japanese authorities were suspicious of the Chinese because of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and murdered thousands of citizen "undesirables" (mostly ethnic Chinese) in the Sook Ching massacre.[168][169] The other ethnic groups of Singapore—such as the Malays and Indians—were not spared. Residents suffered great hardships under Japanese rule over the following three-and-a-half years.[170] Numerous British and Australian soldiers taken prisoner remained in Singapore's Changi Prison and many died in captivity. Thousands of others were transported by sea to other parts of Asia, including Japan, to be used as forced labour on projects such as the Siam–Burma Death Railway and Sandakan airfield in North Borneo. Many of those aboard the ships perished.[171][172]

An Indian revolutionary, Rash Behari Bose, formed the pro-independence Indian National Army (INA) with the help of the Japanese, who were highly successful in recruiting Indian prisoners of war. In February 1942, out of approximately 40,000 Indian personnel in Singapore, about 30,000 joined the INA, of which about 7,000 fought Commonwealth forces in the Burma Campaign and in the northeast Indian regions of Kohima and Imphal; others became POW camp guards at Changi.[173] An unknown number were taken to Japanese-occupied areas in the South Pacific as forced labour. Many of them suffered severe hardships and brutality similar to that experienced by other prisoners held by Japan during the war. About 6,000 survived until they could be liberated by Australian and US forces in 1943–1945, as the war in the Pacific turned in favour of the Allies.[174]

A day after the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, the 25th Army crossed the Singapore Strait and landed on Batam Island without resistance. The Dutch KNIL garrisons stationed on Batam had already abandoned the island on 14 February 1942, after hearing reports of the impending total collapse of Singapore across the strait. Six days after the fall of Singapore, Japanese forces captured Tanjungpinang, marking the complete fall of the Riau Islands under Japanese control.[175]

Commando raids were carried out against Japanese shipping in Singapore Harbour in Operation Jaywick (1943) and Operation Rimau (1944) to varying success.[176] British forces had planned to reconquer Singapore in Operation Mailfist in 1945, but the war ended before it could be carried out. The island was re-occupied in Operation Tiderace by British, Indian and Australian forces following the surrender of Japan in September.[177] Yamashita was tried by a US military commission for war crimes but not for crimes committed by his troops in Malaya or Singapore. He was convicted and hanged in the Philippines on 23 February 1946.[178]

Commemoration

Since 1998, Singapore has observed Total Defence Day on 15 February each year, marking the anniversary of the surrender of Singapore.[179] The concept of Total Defence as a national defence strategy was first introduced in 1984, which serves as a significant reminder that only Singaporeans with a stake in the country can effectively defend Singapore from future threats.[180] Yearly observances on that day include:

- Since 1967, a memorial service is held at the War Memorial Park to recognise civilians who had lost their lives during the Japanese occupation;

- Since 1998, sirens on the Public Warning System are sounded throughout the country (initially at 12.05 p.m.), with the Singapore Civil Defence Force broadcasting an Important Message Signal through the sirens as well as local radio stations; and Singaporean schools conducting emergency preparedness drills, including food and electricity rationing exercises; and

- Since 2015, the timing for the sounding of the sirens has been shifted to 6.20 p.m., corresponding with the actual time of the surrender of Singapore in 1942.[181]

See also

- Fall of the Riau Islands — Continuation of the Battle of Singapore

- British Far East Command

- Japanese order of battle during the Malayan campaign

- Far East prisoners of war

Notes

- ^ On Singapore, the Japanese captured 300 field guns, 180 mortars, 100 anti-aircraft guns, 54 fortress guns, and 108 1-pounder guns, as well as 200 armoured vehicles (Universal Carriers and armoured cars) and 1,800 lorries.[1]

- ^ Blackburn and Hack give a total of 226 for British artillery pieces captured during the siege of Singapore itself, including fortress guns (172 without them),[2] but this appears to exclude 3.7 to 4.5-inch howitzers and 75 mm field guns.[3]

- ^ Chinese: 新加坡戰役;

Malay: Pertempuran Singapura;

Tamil: சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி;

Japanese: シンガポールの戦い - ^ Two brigades from the 8th Australian Division had been dispatched to Singapore and then Malaya in February 1941, while its third brigade had been dispersed to garrison Rabaul, Timor and Ambon.[26]

- ^ The number of Japanese killed and wounded is disputed.[28]

- ^ The war establishment, the paper strength, of an infantry division from 1941 to 1944, was 17,298 men.[40]

- ^ Military analysts later estimated that if the guns had been well supplied with HE shells the Japanese attackers would have suffered heavy casualties but the invasion could not have been prevented by this means alone.[55]

- ^ 64 Sentai lost three Ki-43s and claimed five Hurricanes.[76]

- ^ See the article on David Murnane for a discussion of his role as the Singapore Municipal Water Engineer in assessing the condition of the water supply.

- ^ During this time a number of witnesses claim that Australian deserters were involved in widespread looting, while others were alleged to have pushed women off the gangways to get aboard the departing ships evacuating the civilians.[137] Thompson argues that the identity of these troops is disputed, recounting that around this time some British troops had broken into some of the Australian equipment stores and stolen Australian slouch hats and that further investigations had found that the offending soldiers had worn the black boots issued to British troops, rather than the brown boots worn by Australians.[138]

- ^ "Bennett singled out Indian troops but did not confine his remarks to them. He admitted that towards the end it was all but impossible to return men to their units ... Callaghan recommended that on any clash Percival's report be accepted as more reliable ... Regarding the many reports of Australians hiding in town or trying to escape, Callaghan bluntly admitted "there is a certain amount of truth in both these statements ... This temporary lapse of the Australian on the island and the criticism it has invoked has caused me a lot of uneasiness"."[149]

- ^ According to Woodburn-Kirby the majority of deserters were from administrative units or were men who had only recently arrived in Malaya and were inadequately trained.[150]

- ^ In the 2002 documentary No Prisoners, Major John Wyett, an 8th Australian Division staff officer, claimed the commander of the 22nd Australian Brigade cracked under the pressure, stating, "Taylor was wandering around rather like a man in a sleep walk. He was utterly, utterly, you know, shell-shocked and not able to do very much".[137]

Footnotes

- ^ Allen 2013, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Blackburn & Hack 2004, p. 74.

- ^ Blackburn & Hack 2004, p. 193.

- ^ a b Allen 2013, p. 169.

- ^ Toland 2003, p. 272.

- ^ Warren 2002, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 6–7.

- ^ Keogh 1965, p. 68.

- ^ Costello 2009, p. 71.

- ^ Drea 1991, p. 204.

- ^ Drea 1991, pp. 202, 203.

- ^ a b Keogh 1965, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Costello 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Brayley 2002, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Farrell & Pratten 2011, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Keogh 1962, pp. 62–65.

- ^ Moreman 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Brayley 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Mant 1995, p. 23.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 2001, p. 198.

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 196, 204–205.

- ^ a b Dennis 2008, p. 115.

- ^ Farrell & Pratten 2011, pp. 30, 98, 101.

- ^ Hall 1983, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 67.

- ^ Powell 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 2001, p. 197.

- ^ a b Murdoch 2012.

- ^ Morgan 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 2001, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Wigmore 1986, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 262, 267.

- ^ Moreman 2005, p. 34.

- ^ "2/18th Australian Infantry Battalion". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Keogh 1962, p. 154.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 103–130.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 289.

- ^ Joslen 2003, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 289–290.

- ^ Joslen 2003, p. 60.

- ^ a b Wigmore 1957, p. 290.

- ^ Coello, Terry. "The Malayan Campaign 1941". Orbat.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2005. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ^ a b c Legg 1965, p. 230.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 261.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 262.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 308.

- ^ Lee 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Reid, Richard. "War for the Empire: Malaya and Singapore, Dec 1941 to Feb 1942". Australia-Japan Research Project. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ Thompson 2008, p. 239.

- ^ Smith 2006, pp. 442–443, 527.

- ^ Kirby 1954, p. 361.

- ^ Chung 2011, pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b Coulthard-Clark 2001, p. 202.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 285.

- ^ a b c Thompson 2008, p. 240.

- ^ Felton 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Murfett et al 2011, p. 177.

- ^ Keogh 1962, p. 157.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 163.

- ^ Hall 1983, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Thompson 2008, pp. 286–287, 240.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 308–310.

- ^ a b Costello 2009, p. 199.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 288.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 291.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 297.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 292, 240, 293–295.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 296–300.

- ^ Legg 1965, p. 235.

- ^ Regan 1992, p. 189.

- ^ Shores et al 1992, pp. 276–288.

- ^ Perry 2012, p. 105.

- ^ a b Cull & Sortehaug 2004, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Shores et al 1992, p. 350.

- ^ Grehan & Mace 2015, p. 442.

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Boyne 2002, p. 391.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 273.

- ^ Owen 2001, p. 176.

- ^ Richards & Saunders 1954, p. 40.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 302–303.

- ^ a b c Legg 1965, p. 237.

- ^ Percival's dispatches published in "No. 38215". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 February 1948. pp. 1245–1346. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021.

- ^ Owen 2001, p. 183.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 325.

- ^ a b Wigmore 1957, p. 324.

- ^ a b Legg 1965, p. 236.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 305.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 331.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 333.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 307–309.

- ^ a b Wigmore 1957, p. 329.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 309.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 310.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Leasor 2001, p. 246.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 312.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 314.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 348–350.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 179.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 66.

- ^ Perry 2012, p. 104.

- ^ Smith 2006, p. 509.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 316.

- ^ Kirby 1954, p. 410.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 354.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 180.

- ^ Shores et al 1992, p. 383.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 183.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 323.

- ^ a b Hall 1983, p. 184.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Keogh 1962, p. 170.

- ^ a b Keogh 1962, p. 171.

- ^ Elphick, Peter (2002). "Viewpoint: Cover-ups and the Singapore Traitor Affair". Four Corners Special: No Prisoners. Australian Broadcasting Commission. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- ^ Smith 2006, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Elphick 1995, p. 353.

- ^ a b Wigmore 1957, p. 369.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 331–333.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 332.

- ^ Perry 2012, p. 95.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 375.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 333.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 333–334.

- ^ a b c Thompson 2005, p. 334.

- ^ Partridge, Jeff. "Alexandra Massacre". National Ex-Services Association United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 18 October 2005. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ^ Perry 2012, p. 107.

- ^ "Soldier's account of Japanese World War Two massacre to be auctioned". The Telegraph. 11 August 2008. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ a b Wigmore 1957, p. 377.

- ^ a b Costello 2009, p. 198.

- ^ a b c "Transcript". Four Corners Special: No Prisoners. Australian Broadcasting Commission. 2002. Archived from the original on 26 February 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ a b Thompson 2008, p. 241.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 356.

- ^ Smith 2006.

- ^ Hall 1983, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 378.

- ^ Hall 1983, p. 193.

- ^ "Lieutenant General Henry Gordon Bennett, CB, CMG, DSO". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Legg 1965, pp. 255–263.

- ^ Hopkins 2008, p. 96.

- ^ a b Morgan 2013, p. 13.

- ^ a b Murfett et al 2011, p. 360.

- ^ Kirby 1954, p. 401.

- ^ Murfett et al 2011, p. 350.

- ^ Elphick 1995, p. 352.

- ^ Thompson 2005, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 355.

- ^ a b Dennis 2008, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 2001, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Wigmore 1957, p. 382.

- ^ Hauner 2005, pp. 173–179.

- ^ Churchill 2002, p. 518.

- ^ Moran 1966, p. 29.

- ^ Warren 2002, p. 295.

- ^ "Battle of Singapore". World History Group. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ Legg 1965, p. 248.

- ^ Toland 1970, p. 277.

- ^ Abshire 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Blackburn & Hack 2004, p. 132.

- ^ Hasluck, Paul (1970). The Government and the People 1942–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 4 – Civil. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 70–71. 6429367X.

- ^ Hall 1983, pp. 211–212.

- ^ WaiKeng Essay Archived 1 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine 'Justice Done? Criminal and Moral Responsibility Issues in the Chinese Massacres Trial Singapore, 1947' Genocide Studies Program. Working Paper No. 18, 2001. Wai Keng Kwok, Branford College/ Yale university

- ^ Church 2012, Chapter 9: Singapore.

- ^ Dennis 2008, pp. 126, 431–434.

- ^ Kinvig 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Warren 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Brayley 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Jan A. Krancher, ed. (2010), The Defining Years of the Dutch East Indies, 1942-1949, McFarland, ISBN 978-0786481064, retrieved 22 February 2021

- ^ Horner 1989, p. 26.

- ^ Bose 2010, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Smith 2006, pp. 556–557.

- ^ "Sirens". The New Paper. 14 February 1998.

On Sunday at noon, the sirens of the Public Warning System will sound island-wide for one minute. This is in conjunction with total defence day, to mark the fall of Singapore to the Japanese during World War II.

- ^ Jacob, Paul; Wai, Ronnie (6 January 1984). "Your say in our defence Our defence must be total — Chok Tong". The Straits Times. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Cheong, Danson (11 February 2015). "Public Warning System sirens to broadcast message on Sunday | The Straits Times". The Straits Times. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

References

Books

- Abshire, Jean (2011). The History of Singapore. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37743-3. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Allen, Louis (2013). Singapore 1941–1942 (2nd rev. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-19425-3.

- Blackburn, Kevin; Hack, Karl (2004). Did Singapore Have to Fall? Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress. London: Routledge. ISBN 0203404408. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Bose, Romen (2010). The End of the War: Singapore's Liberation and the Aftermath of the Second World War. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-9-81-443547-5.

- Boyne, Walter (2002). Air Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-729-0.

- Brayley, Martin (2002). The British Army 1939–45: The Far East. Men at Arms. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-238-8.

- Cull, Brian; Sortehaug, Paul (2004). Hurricanes Over Singapore: RAF, RNZAF and NEI Fighters in Action Against the Japanese Over the Island and the Netherlands East Indies, 1942. London: Grub Street Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904010-80-7.

- Church, Peter, ed. (2012). A Short History of South-East Asia (5th ed.). Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-35044-7.

- Chung, Ong Chit (2011). Operation Matador: World War II—Britain's Attempt to Foil the Japanese Invasion of Malaya and Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-9-81-443544-4.

- Churchill, Winston (2002) [1959]. The Second World War (Abridged ed.). London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6702-9.

- Corrigan, Gordon (2010). The Second World War: A Military History. New York: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-0-85789-135-8.

- Costello, John (2009) [1982]. The Pacific War 1941–1945. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-688-01620-3.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (2nd ed.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-634-7.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin; Bou, Jean (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Elphick, Peter (1995). Singapore: The Pregnable Fortress. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-64990-9.

- Farrell, Brian; Pratten, Garth (2011) [2009]. Malaya 1942. Australian Army Campaigns Series–5. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Army History Unit. ISBN 978-0-9805674-4-1.

- Felton, Mark (2008). The Coolie Generals. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-767-9.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Vol. I. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Grehan, John; Mace, Martin (2015). Disaster in the Far East 1940–1942. Havertown: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-5305-8.

- Hall, Timothy (1983). The Fall of Singapore 1942. North Ryde, New South Wales: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-454-00433-5.

- Hauner, Milan (2005). Hitler: A Chronology of his Life and Time. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-58449-5.

- Hopkins, William B. (2008). The Pacific War: The Strategy, Politics, and Players that Won the War. Minneapolis: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-3435-5.

- Horner, David (1989). SAS: Phantoms of the Jungle. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86373-007-5.

- Joslen, H. F. (2003) [1960]. Orders of Battle: Second World War, 1939–1945. Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-474-1.

- Keogh, Eustace (1962). Malaya 1941–42. Melbourne: Printmaster. OCLC 6213748.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne: Grayflower. OCLC 7185705.

- Kinvig, Clifford (2005). River Kwai Railway: The Story of the Burma-Siam Railroad. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-021-0.

- Kirby, Stanley Woodburn (1954). War Against Japan: The Loss of Singapore. History of the Second World War. Vol. I. HMSO. OCLC 58958687.

- Leasor, James (2001) [1968]. Singapore: The Battle That Changed The World. London: House of Stratus. ISBN 978-0-7551-0039-2. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Lee, Edwin (2008). Singapore: The Unexpected Nation. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. OCLC 474265624.

- Legg, Frank (1965). The Gordon Bennett Story: From Gallipoli to Singapore. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 3193299.

- Lloyd, Stu (2012). The Missing Years: A POW's Story from Changi to Hellfire Pass. Dural, New South Wales: Rosenberg. ISBN 978-1-921719-20-2.

- Lodge, A.B. (1986). The Fall of General Gordon Bennett. Sydney, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 0-86861-882-9.

- Mant, Gilbert (1995). Massacre at Parit Sulong. Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 978-0-86417-732-2.

- Moran, Charles (1966). Churchill Taken from the Diaries of Lord Moran: The Struggle for Survival 1940–1965. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 1132505204.

- Moreman, Tim (2005). The Jungle, The Japanese and the British Commonwealth Armies at War, 1941–45: Fighting Methods, Doctrine and Training for Jungle Warfare. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-4970-2.

- Murfett, Malcolm H.; Miksic, John; Farell, Brian; Shun, Chiang Ming (2011). Between Two Oceans: A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971 (2nd ed.). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia. OCLC 847617007.

- Owen, Frank (2001). The Fall of Singapore. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-139133-5.

- Perry, Roland (2012). Pacific 360: Australia's Battle for Survival in World War II. Sydney, New South Wales: Hachette Australia. ISBN 978-0-7336-2704-0.

- Powell, Alan (2003). The Third Force: ANGAU's New Guinea War, 1942–46. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551639-5.

- Rai, Rajesh (2014). Indians in Singapore, 1819–1945: Diaspora in the Colonial Port City. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-809929-1.

- Regan, Geoffrey (1992). The Guinness Book of Military Anecdotes. Enfield: Guinness. ISBN 978-0-85112-519-0.

- Richards, Dennis; Saunders, Hilary St. George (1954). The Fight Avails. Royal Air Force 1939–1945. Vol. II. London: HMSO. OCLC 64981538. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- Shores, Christopher F.; Cull, Brian; Izawa, Yasuho (1992). Bloody Shambles: The First Comprehensive Account of the Air Operations over South-East Asia December 1941 – April 1942: Drift to War to the Fall of Singapore. Vol. I. London: Grub Street Press. ISBN 978-0-948817-50-2.

- Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-101036-6.

- Thompson, Peter (2005). The Battle for Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II. London: Portrait Books. ISBN 0-7499-5099-4.

- Thompson, Peter (2008). Pacific Fury: How Australia and Her Allies Defeated the Japanese Scourge. North Sydney: William Heinemann. ISBN 978-1-74166-708-0.

- Toland, John (1970). The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-44311-9.

- Toland, John (2003). The Rising Sun. New York: The Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-8129-6858-3.

- Toye, Hugh; Mason, Philip (2006). Subhash Chandra Bose, (The Springing Tiger): A Study of a Revolution (Thirteenth Jaico impression ed.). Mumbai. ISBN 81-7224-401-0. OCLC 320977356.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Warren, Alan (2007) [2002]. Britain's Greatest Defeat: Singapore 1942. London: Hambeldon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-597-0.

- Warren, Alan (2002). Singapore: Britain's Greatest Defeat. South Yarra, Victoria: Hardie Grant. ISBN 981-0453-205.

- Wigmore, Lionel, ed. (1986). They Dared Mightily (2nd ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 978-0-642-99471-4.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Vol. IV. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134219. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

Journals

- Drea, Edward (April 1991). "Reading Each Other's Mail: Japanese Communication Intelligence, 1920–1941". The Journal of Military History. 55 (2): 185–206. doi:10.2307/1985894. ISSN 1543-7795. JSTOR 1985894.

- Morgan, Joseph (2013). "A Burning Legacy: The Broken 8th Division". Sabretache. LIV (3, September). Military Historical Society of Australia: 4–14. ISSN 0048-8933.

Newspapers

- Murdoch, Lindsay (15 February 2012). "The Day The Empire Died in Shame". The Sydney Morning Herald. ISSN 0312-6315. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

Further reading

- Afflerbach, Holger; Strachan, Hew (2012). How Fighting Ends: A History of Surrender. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199693627.

- Bose, Romen (2005). Secrets of the Battlebox: The History and Role of Britain's Command HQ during the Malayan Campaign. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9789812610645.

- Bose, Romen (2006). Kranji: The Commonwealth War Cemetery and the Politics of the Dead. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9789812612755.

- Burton, John (2006). Fortnight of Infamy: The Collapse of Allied Airpower West of Pearl Harbor. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-096-X. OCLC 69104264. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- Cawood, Ian (2013). Britain in the Twentieth Century. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781136406812.

- Cull, Brian (2008). Buffaloes over Singapore: RAF, RAAF, RNZAF and Dutch Brewster Fighters in Action Over Malaya and the East Indies 1941–1942. Grub Street Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904010-32-6.

- Dixon, Norman (1976). On the Psychology of Military Incompetence. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465052530.

- Farrell, Brian (2005). The Defence and Fall of Singapore 1940–1942. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 9780752434780.

- Kelly, Terence (2008). Hurricanes Versus Zeros: Air Battles over Singapore, Sumatra and Java. South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-622-1.

- Kinvig, Clifford (1996). Scapegoat: General Percival of Singapore. London: Brassey's. ISBN 9781857531718.

- Percival, Lieutenant-General A.E. (1948). Operations of Malaya Command from 8th December 1941 to 15th February 1942. London: UK Secretary of State for War. OCLC 64932352.

- Seki, Eiji (2006). Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940. London: Global Oriental. ISBN 1-905246-28-5. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Smyth, John George (1971). Percival and the Tragedy of Singapore. London: MacDonald and Company. OCLC 213438.

- Tsuji, Masanobu (1960). Japan's Greatest Victory, Britain's Worst Defeat: The Capture of Singapore, 1942. Singapore: The Japanese Version. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Uhr, Janet (1998). Against the Sun: The AIF in Malaya, 1941–42. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781864485400.

- Woodburn Kirby, S.; Addis, C. T.; Meiklejohn, J. F.; Wards, G. T.; Desoer, N. L. (2004) [1957]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War Against Japan: The Loss of Singapore. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (facs. pbk. repr. Naval & Military Press, Ukfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-060-3.

External links

- Bicycle Blitzkrieg – The Japanese Conquest of Malaya and Singapore 1941–1942

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Second World War – the Far East

- The diary of one British POW, Frederick George Pye of the Royal Engineers