Cachao

Cachao | |

|---|---|

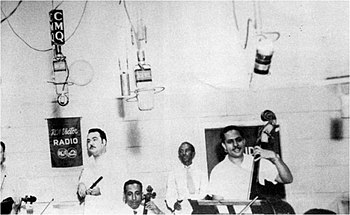

Cachao in Havana, 1960 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Israel López Valdés[1] |

| Born | September 14, 1918 Habana Vieja, La Habana, Cuba |

| Died | March 22, 2008 (aged 89) Coral Gables, Florida, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument | Double bass |

| Years active | 1926–2008 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | www.israelcachaolopez.com |

Israel López Valdés (September 14, 1918 – March 22, 2008), better known as Cachao (/kəˈtʃaʊ/ kə-CHOW), was a Cuban double bassist and composer. Cachao is widely known as the co-creator of the mambo and a master of the descarga (improvised jam sessions).[2] Throughout his career he also performed and recorded in a variety of music styles ranging from classical music to salsa. An exile in the United States since the 1960s, he only achieved international fame following a career revival in the 1990s.

Born into a family of musicians in Havana, Cachao and his older brother Orestes were the driving force behind one of Cuba's most prolific charangas, Arcaño y sus Maravillas. As members of the Maravillas, Cachao and Orestes pioneered a new form of ballroom music derived from the danzón, the danzón-mambo, which subsequently developed into an international genre, mambo. In the 1950s, Cachao became famous for popularizing improvised jam sessions known as descargas. He emigrated to Spain in 1962, and moved to the United States in 1963, starting a career as a session and live musician for a variety of bands in New York during the rise of boogaloo, and later, salsa.

In the 1970s, Cachao fell into obscurity after moving to Las Vegas and later Miami, releasing albums sporadically as a leader. In the 1990s, he was re-discovered by actor Andy García, who brought him back to the forefront of the Latin music scene with the release of a documentary and several albums. Before his death in 2008, Cachao had earned a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and several Grammy Awards. He is ranked number 24 on Bass Player magazine's list of "The 100 Greatest Bass Players of All Time".[3]

Biography

Early life and career

Cachao was born on September 14, 1918, in Belén, a neighbourhood in Old Havana, into a family of musicians, many of them bassists—around 40 or more in his extended family.[4][5] He was born and raised in the same house in which José Martí was born.[6][7] His nickname and stage name Cachao was given to him by his grandfather Aurelio López,[6][8] from the Spanish word "cachondeo" (banter).[7][9]

Cachao began his musical career in 1926, taught by his father, Pedro López, and his older brother, multi-instrumentalist Orestes López, nicknamed "Macho".[6] As an 8-year-old bongo player, he joined a children's son cubano septet directed by a 14-year old Roberto Faz.[6] A year later, already on double bass, he provided music for silent movies in his neighborhood theater, in the company of a pianist who would become a true superstar, cabaret performer Ignacio Villa, known as Bola de Nieve.[10] Work at the cinema ended in 1930 when talkies began to be shown in Cuba.[11]

His parents made sure he was classically trained, first at home and then at a conservatory. In his early teens he was already playing contrabass with the Orquesta Filarmónica de La Habana (of which Orestes was a founding member), under the baton of guest conductors such as Herbert von Karajan, Igor Stravinsky and Heitor Villa-Lobos.[9] He played with the orchestra from 1930 to 1960.[4]

Las Maravillas and the origin of mambo

Cachao's and Orestes' rise to fame came with the charanga Arcaño y sus Maravillas, founded by flautist Antonio Arcaño. As members of the group they composed literally thousands of danzones together and were a major influence on Cuban music from the 1930s to the 1950s. They introduced the nuevo ritmo ("new rhythm") in the late 1930s, which transformed the danzón by introducing a syncopated final section open to the improvisation of the players and dancers. This section, known as the mambo, was named after the danzón "Mambo", co-written by Cachao and Orestes, which—according to Cachao—referred to the word for "story or tale" used by Kongos and Lucumís in Cuba.[7][9] In the words of Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante, it was the "mother of all mambos".[12] In their vast repertoire were also compositions by other songwriters such as "Isora Club", written by their sister Coralia López, as well as arrangements of standards such as "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" and songs by George Gershwin and Jelly Roll Morton.[6] The Maravillas, or La Radiofónica as they were popularly known, became a radio sensation in the mid-1940s, having their own program and expanding their lineup to 14 musicians in 1944.[13] The need to constantly write music sheets for each member of the band was one of the reasons why Cachao left the group in 1949.[14] He then joined Blanquita Theater orchestra, whose fifty members played in Broadway-style revues. The Maravillas went on for another ten years.[14] Their swan song, released in 1957, was "Chanchullo", composed by Cachao himself, who organized the session. The song became a hit in the United States as the basis for Tito Puente's "Oye cómo va", although Puente denied copying Cachao's composition.

Descargas at Panart studios

One day in 1957, Cachao gathered a group of musicians in the early hours of the morning (from 4 to 9 AM), energized from playing gigs at Havana's popular nightclubs, to jam in front of the mics of a recording studio.[6] The resulting descargas, known to music aficionados worldwide as Cuban jam sessions, revolutionized Afro-Cuban popular music. Under Cachao's direction, these masters improvised freely in the manner of jazz, but their vocabulary was Cuba's popular music. These descargas were released in 1957 by the Panart label under the title Cuban Jam Sessions in Miniature,[15] which followed the longer descargas by Julio Gutiérrez (Cuban Jam Sessions Vol. 1 and 2), released also by Panart. They have been named by many critics as one of the most essential Cuban records of the 1950s, including being cited by the book 1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die. Between 1957 and 1959 he recorded many more descargas at Panart studios. These recordings were released in the following years by Kubaney and Maype, and re-released by EGREM. He also recorded descargas with Tojo's orchestra and Chico O'Farrill's All-Stars Cubano amongst other ensembles. He worked alongside Peruchín, Tata Güines and Alejandro "El Negro" Vivar.

Exile

In 1958, at the height of the Cuban Revolution, Cachao's wife left Cuba for New Jersey, and in 1962, three years into Fidel Castro's communist regime, Cachao crossed the Atlantic on a ship along with 13 other musicians.[7][11] After 21 days, they reached the Canary Islands. Cachao settled in Madrid, where he joined Ernesto Duarte as a member of his orchestra, Orquesta Sabor Cubano.[7][11] In Madrid, Cachao also performed with other artists such as Pérez Prado.[7][9] One year later, in 1963, Cachao reunited with his wife in New York, where he played with Charlie Palmieri, José Fajardo, Tito Rodríguez, Tito Puente and Machito, among others.[7] Cachao was one of the most in-demand bassists in New York, along with Alfonso "El Panameño" Joseph and Bobby "Big Daddy" Rodríguez. Joseph and Cachao substituted for each other over a span of five years, performing at nightclubs and venues such as the Palladium Ballroom, the Roseland, the Birdland, Havana San Juan and Havana Madrid. While Cachao was performing with Machito's orchestra in New York, Joseph was recording and performing with Cuban conga player Cándido Camero. When Joseph left Cándido's band to work with Charlie Rodríguez and Johnny Pacheco, it was Cachao who took his place in Cándido's band.

After a decade in New York, Cachao moved to Las Vegas, where he played in Pupi Campo's band at the casinos and as a pianist at a piano bar.[7] In 1977, Cachao recorded with drummers Louis Bellson and Walfredo de los Reyes the experimental album Ecué, where he played piano on the title track. Most significantly, he was brought back into the recording studio by musicologist René López to record two albums as a leader (Cachao y su Descarga 77 and Dos), his first in 15 years. These LPs constituted a sort of "rediscovery" of Cachao for the incipient salsa scene in New York. In 1978, Cachao moved to Miami,[16] where he played at events such as baptisms, comuniones, quinceañeras and weddings. Despite his lower profile, Cachao recorded several albums with pianist Paquito Hechevarría for the Tania record label, including one as a leader in 1986, Maestro de Maestros: Cachao y su Descarga '86.

Late career

In 1989, actor Andy García contacted Cachao at the San Francisco Jazz Festival, where he was playing with John Santos and Carlos Santana.[17] García asked him if he would be interested in a tribute concert and documentary film being made in his honor, which Cachao proudly accepted.[7][11] The concert took place in Miami on July 31, 1992, and it was the centerpiece of the four-day 16 mm shoot that yielded Cachao... como su ritmo no hay dos, García's film, released the following year.[18][19] The success of the concert and film spurred the recording of two new albums, Master Sessions Vol. 1 (1994) and Vol. 2 (1995), as well as international tours.[2] This led to a second "rediscovery" of Cachao, as well as numerous accolades, including several Grammy and Hall of Fame awards.

As a leader, Cachao recorded two more albums to critical acclaim, Cuba linda (2000) and Ahora sí (2004). In 2000, he recorded with Bebo Valdés for Fernando Trueba's concert film Calle 54 and for the album El arte del sabor. He made his last studio recordings as a sideman for Gloria Estefan on 90 Millas (2007).[20] His last concert took place in Miami in September 2007 and was released as a posthumous live album, The Last Mambo, by Sony Music in 2011. In February 2008, Cachao signed a contract with Penguin Books to write a book about his life,[11] which never materialized due to his passing one month later. At the time, Cachao was preparing to record another album[11] and had eight concerts in Europe scheduled for 2008.[21]

Death

Cachao died on the morning of March 22, 2008, in Coral Gables, Florida, at the age of 89.[20] He died from complications resulting from kidney failure. On March 26 and 27, a public open-casket funeral, led by Alberto Cutié, was held at St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church in Miami.[21][22] On March 27, he was buried at Vista Memorial Gardens in Miami Lakes.[21][23]

Family

Cachao was part of a large musical family which at one time had "35 bassists" across multiple generations, although many played other instruments as well.[7][11] Cachao's older brother, Orestes, played 12 instruments, including bass, cello, harp and piano, and Cachao himself played bass, piano, bongos, tres and trumpet.[7][11] His sister Coralia was also a bassist and bandleader, but is perhaps best known as a songwriter for her danzón "Isora Club", a standard of the genre. Orestes' son, Orlando, was nicknamed Cachaíto after his uncle Cachao. He was a prolific bassist as well and one of the mainstays of the famed Buena Vista Social Club group, named after one of Cachao's danzones, "Social Club Buenavista". In 2001, Cachaíto recorded his only album as a leader, featuring two songs composed by Cachao.

Cachao was married to Ester Buenaventura from 1946 until her death in May 2005.[17] They were survived by their only daughter, María Elena.[22]

Awards and recognition

Honors

In 1994, Cachao was inducted into Billboard's Latin Music Hall of Fame.[24] He was a recipient of a 1995 National Heritage Fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which is the highest honor in the folk and traditional arts in the United States.[25] In 1999, Cachao was inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame.[26] He also received a Lifetime Achievement Award a year later.[27] In 2003, Cachao was awarded the 2,219th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[17] On June 11, 2006, he was honored by Union City, New Jersey with a star on the Walk of Fame at Union City's Celia Cruz Park.[28] On November 7, 2006, Cachao received an Honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music during Berklee's Latin Culture Celebration.[29] At the time of his death, the University of New Haven had also decided to award an Honorary Doctorate to Cachao.[21]

Grammy Awards

Cachao has won several Grammy Awards for both his own work and his contributions on albums by Latin music stars, including Gloria Estefan. In 1994, he won a Grammy for Master Sessions Volume 1. In 2003, he won a Latin Grammy for Best Traditional Tropical Latin Album together with Bebo Valdés and Carlos "Patato" Valdés for El arte del sabor. Cachao won a further Grammy in 2005 for his album ¡Ahora Sí!. In 2012, his posthumous live album The Last Mambo won the Grammy Award in the Best Tropical Latin album category.

Tributes

Cachao has received numerous tributes in the form of dedicated concerts, compositions and recordings from other musicians. The first notable tribute concert to Cachao was organized by musicologist René López and held at Avery Fisher Hall in New York City in 1976.[6][30] Although the event gathered many of the major exponents of Afro-Cuban music in the country, it received little attention from the press.[6][30]

In 1987, a tribute concert was held at the Hunter College auditorium in New York City in honor of Cachao. The ensemble was directed by pianist Charlie Palmieri and featured Alfredo "Chocolate" Armenteros, Orlando "Puntilla" Ríos, Pupi Legarreta, Tito Puente, as well as Cachao himself.[31]

In 1993, the Puerto Rican salsa supergroup Descarga Boricua recorded the track "Homenaje a Cachao" for the album ¡Esta sí va!, while pianist Hilario Durán recorded a different piece with the same name for his 2001 album Havana Remembered. Bebo Valdés composed and recorded the piece "Cachao, creador del mambo" in 2004, and re-recorded a segment of the song for the film Chico & Rita in 2010.

In November 2005, a tribute performance dedicated to Cachao took place during the 6th Annual Latin Grammy Awards. It was presented by Andy García and featured Bebo Valdés, Generoso Jiménez, Arturo Sandoval, Johnny Pacheco, as well Cachao himself.[32]

In February 2008, Paquito D'Rivera premiered Conversaciones con Cachao, a symphonic suite dedicated to Cachao, during the Festival de Música de Canarias (Canary Islands Music Festival). The orchestra was directed by Pablo Zinger.[33]

A month after Cachao's death, a second documentary film by Andy García was released; Cachao: Uno más premiered in April 2008 at the San Francisco International Film Festival.[34] The inspiration for Cachao: Uno más, made by San Francisco State University's DOC Film Institute, came largely from a concert Cachao played at Bimbo's 365 Club in San Francisco in 2005. The film's premiere was followed by a tribute concert with the John Santos Band at Yoshi's Jazz Club SF.

After Cachao's death, his backing band continued to perform as Cachao's Mambo All-Stars and they recorded an album in his honour, Como siempre.[35]

On March 15, 2019, a concert titled Mambo: 100 Years of the Master - Cachao was held in Miami, 100 years after Cachao's birth. It featured 97-year-old Cándido Camero and 89-year-old Juanito Márquez, among others. The latter arranged some of the songs Cachao was preparing to record in 2008 at the time of his passing, which were performed for the first time 11 years later at the concert.[36][37]

Discography

As leader

Singles

|

As sidemanWith All-Stars Cubano

With Arcaño y sus Maravillas

With Joe Cain

With Charanga Caribe

With Conjunto Yumurí

With Kako

With Chano Montes y su Conjunto

With Carlos Montiel

With Orquesta Oriental

With Patato & Totico

With Eddie Palmieri

With Tito Rodríguez

With The Salsa All Stars

With Bebo Valdés

|

Filmography

- Cachao... como su ritmo no hay dos (1993)

- Cachao: Uno más (2008)

References

- ^ Davis, John S. (2020). "Cachao". Historical Dictionary of Jazz. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-5381-2815-2.

- ^ a b Ankeny, Jason. "Cachao - Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Bass Players". bassplayer.com. NewBay Media. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Pareles, Jon, New York Times: "Cachao, Mambo’s Inventor, Dies at 89", The New York Times, March 24, 2008.

- ^ Orovio, Helio, "Cuban Music from A to Z", Duke University Press, 2003. Cf. pp 125-126 for article on Israel López.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pagano, César (February–March 2007). "¡Cómo Cachao no hay dos!" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2017-04-30. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Entrevista con Israel López "Cachao". 2003.

- ^ Tamargo, Luis (August 1, 2004). "Cachao: a conversation with the godfather of the Cuban bass". Latin Beat Magazine. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Entrevista a Cachao por Eloy Cepero (II). February 28, 2008.

- ^ "Israel ‘Cachao’ López: Cuban double-bassist and composer who, with his brother, invented the Cuban dance style of mambo in the late 1930s", The Times (London), March 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Entrevista a Cachao por Eloy Cepero (I). February 28, 2008.

- ^ Cahill, Greg. "Interview with Cachao[permanent dead link]", String Magazine, March 2005.

- ^ Fernández-Larrea, Ramón (2007). Kabiosiles: los músicos de Cuba (in Spanish). Barcelona, Spain: Linkgua. p. 53. ISBN 9788498166194.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Padura Fuentes, Leonardo (1999). "Cachao: Mi idioma es un contrabajo". La Gaceta de Cuba, no. 5 (in Spanish). La Jiribilla. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ 1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die. Tom Moon, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7611-3963-8]

- ^ Martín, Lydia (22 March 2008). "The life of the legendary Cachao". Miami Herald. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Mauleón, Rebecca (March 7, 2008). "Cachao!". Bass Player. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (15 September 1993). "'Cachao' an Infectious, Graceful Concert Film". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Gómez, Lourdes (21 November 1993). "Andy Garcia alivia sus penas con la música". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Fallece Cachao, legendario contrabajista cubano". El País (in Spanish). 22 March 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Con música darán el último adiós a Israel López "Cachao" en Miami". Excelsior California (in Mexican Spanish). March 25, 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Mis pastelitos de Guayaba con el creador del Mambo". Proceso Digital (in Spanish). October 14, 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Clary, Mike (March 28, 2008). "Goodbye, mambo king". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Lannert, John (May 21, 1994). "First Latin Music Awards Recognize Range of Talent". Billboard. Vol. 106, no. 32. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. LM-52. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- ^ "NEA National Heritage Fellowships 1995". www.arts.gov. National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ de Fontenay, Sounni (7 December 1998). "International Latin Music Hall of Fame". Latin American Rhythm Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "International Latin Music Hall of Fame Announces Year 2000 Inductees". 1 March 2000. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Rosero, Jessica. "Viva la comunidad Cubano North Hudson celebrates at the annual Cuban Day Parade" Archived 2017-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Hudson Reporter June 18, 2006

- ^ Dorbu, Mitzi (December 1, 2006). "Mambo maestro "Cachao" receives honorary doctorate during Berklee's Latin Culture Celebration". Latin Beat Magazine. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Fernández, Raúl A. (2006). From Afro-Cuban Rhythms to Latin Jazz. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780520939448.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (26 November 1987). "Jazz: Tribute to Lopez". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Tribute to Cachao - Latin Grammys". Archive.org. National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. 3 November 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ García Saleh, Alberto (18 February 2008). "Paquito D'Rivera: "Se ha perdido espontaneidad"". La Provincia (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Rose, Roger (June 3, 2008). "Cuban Maestro: Sizzles at SF Film Fest". CineSource Magazine. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Cachao's Mambo All Stars Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Tempest Entertainment.

- ^ Cantor-Navas, Judy (5 February 2019). "Seven New Compositions by Cachao to be Performed at Miami Tribute Concert: Exclusive". Billboard. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Cantor-Navas, Judy (19 March 2019). "Nonagenarian Cándido Camero Takes Center Stage at Cachao Tribute Concert". Billboard. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

External links

- Moore, Robin (2001). "Cachao". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- "Cachao". Encyclopedia Britannica. March 18, 2020. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Cachao, Rate Your Music.

- Cachao, Discogs.

- Cachao at IMDb

- Cuba's Cachao is king of Tumbao

- Cachao gets star on Walk of Fame

- "Cachao: Uno Más"