Intramuros

Intramuros | |

|---|---|

District | |

Clockwise, from top left: Plaza Moriones, Baluarte de San Diego, Ayuntamiento de Manila, San Agustin Church, Plaza San Luís Complex, Fort Santiago | |

| Nicknames: Old Manila; the Walled City | |

| Motto(s): Insigne y siempre leal Distinguished and ever loyal | |

| |

| Coordinates: 14°35′29″N 120°58′25″E / 14.59147°N 120.97356°E | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | National Capital Region |

| City | Manila |

| Congressional District | 5th District of Manila |

| Barangays | 5 |

| Settled | June 12, 1571 |

| Founded by | Miguel López de Legazpi |

| Government | |

| • Administrator of Intramuros | Atty. Joan M. Padilla |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.67 km2 (0.26 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

• Total | 6,103 |

| • Density | 9,100/km2 (24,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (Philippine Standard Time) |

| Zip codes | 1002 |

| Area codes | 2 |

| Website | intramuros |

Intramuros (lit. 'within the walls' or 'inside the walls') is the 0.67-square-kilometer (0.26 sq mi) historic walled area within the city of Manila, the capital of the Philippines. It is administered by the Intramuros Administration with the help of the city government of Manila.[2]

Intramuros comprises a centuries-old historic district, entirely surrounded by fortifications, that was considered at the time of the Spanish Empire to be the entire City of Manila. Other towns and arrabales (suburbs) located beyond the walls that are now districts of Manila were referred to as extramuros, Spanish for "outside the walls",[3][4] and were independent towns that were only incorporated into the city of Manila during the early 20th century.

Intramuros served as the seat of government of the Captaincy General of the Philippines, a component realm of the Spanish Empire, housing the colony's governor-general from its founding in 1571 until 1865, and the Real Audiencia of Manila until the end of Spanish rule during the Philippine Revolution of 1898. The walled city was also considered the religious and educational center of the Spanish East Indies.[5] Intramuros was also an economic center as the Asian hub of the Manila galleon trade, carrying goods to and from Acapulco in what is now Mexico.

During the early 20th century, under the administration of American colonial authorities, land reclamation and the construction of the Manila South Port subsequently moved the coastline westward and obscured the walls and fort from the bay, while the moat surrounding the fortifications was drained and turned into a recreational golf course. The Battle of Manila in 1945 during World War II entirely flattened Intramuros. Though reconstruction efforts began immediately after the war, many of its original landmarks are still lost today; under the Intramuros Administration, Intramuros is still in the process of postwar reconstruction and revival of its cultural heritage.

While Intramuros is no longer the seat of the contemporary Philippine government, several Philippine government agencies are headquartered in Intramuros. Moreover, Intramuros remains a significant educational center as part of the city's University Belt. Several offices of the Philippine Catholic Church are also found in the district.

Intramuros was designated a National Historical Landmark in 1951. The fortifications of Intramuros were declared National Cultural Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines, owing to its historic and cultural significance.[6] San Agustín Church, one of four UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the entry Baroque Churches of the Philippines, is located within the walled district. Intramuros and other historical sites in Manila are currently being proposed by the UNESCO Philippine National Commission to the country's tentative list for future UNESCO World Heritage Site inscription as The Walled City and Historic Monuments of Manila.[7]

History

Pre-Hispanic period

The strategic location of Manila along the bay and at the mouth of the Pasig River made it an ideal location for the Tagalog tribes and kingdoms to trade with merchants from what would be today's China, India, Borneo, and Indonesia. The prehistoric polity of Maynila was located where Intramuros would be built.

In 1564, Spanish explorers led by Miguel López de Legazpi sailed from New Spain, now Mexico, and arrived on the island of Cebu on February 13, 1565, establishing the first Spanish capitania in the Philippines. Having heard from the natives about the rich resources in Maynila, Legazpi dispatched two of his lieutenant-commanders, Martín de Goiti and Juan de Salcedo, to explore the island of Luzon.

The Spaniards arrived on the island of Luzon in 1570. After quarrels and misunderstandings between the Muslim natives and the Spaniards, they fought for control of the land and settlements. After several months of warfare the natives were defeated, and the Spaniards made a peace pact with the councils of Rajah Sulaiman III, Lakan Dula, and Rajah Matanda who handed over the city to the Spaniards.

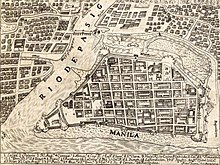

Spanish colonial period (1571–1898)

Legazpi declared the area of Manila as the new capital of the Spanish colony on June 24, 1571, because of its strategic location and rich resources. He also proclaimed the sovereignty of the Monarchy of Spain over the whole archipelago. King Philip II of Spain delighted at the new conquest achieved by Legazpi and his men, awarding the city a coat of arms and declaring it as: Ciudad Insigne y Siempre Leal (English: "Distinguished and Ever Loyal City"). It was settled and became the political, military, and religious center of the Spanish Empire in Asia.

The city was in constant danger of natural and man-made disasters and worse, attacks from foreign invaders. In 1574, a fleet of Chinese pirates led by Limahong attacked the city and destroyed it before the Spaniards drove them away. The colony had to be rebuilt again by the survivors.[8] These attacks prompted the construction of the wall.

The city of stone began during the rule of Governor-General Santiago de Vera.[9] The city was planned and executed by Jesuit Priest Antonio Sedeno[8] in accordance with the Laws of the Indies and was approved by King Philip II's Royal Ordinance that was issued in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain. The succeeding governor-general, Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas brought with him from Spain the royal instructions to carry into effect the said decree stating that "to enclose the city with stone and erect a suitable fort at the junction of the sea and river". Leonardo Iturriano, a Spanish military engineer specializing in fortifications, headed the project. Chinese and Filipino workers built the walls.

Fort Santiago was rebuilt and a circular fort, known as Nuestra Senora de Guia, was erected to defend the land and sea on the southwestern side of the city. Funds came from a monopoly on playing cards and fines imposed on its excessive play. Chinese goods were taxed for two years. Designed by Geronimo Tongco and Pedro Jusepe,[10] construction of the walls began on 1590 and continued under many governor-generals until 1872. By the middle of 1592, Dasmarinas wrote the King about the satisfactory development of the new walls and fortification.[11] Since the construction was carried on during different periods and often far apart, the walls were not built according to any uniform plan.[9]

Improvements continued during the terms of the succeeding Governor-Generals. Governor-General Juan de Silva executed certain work on the fortifications in 1609 which was improved by Juan Niño de Tabora in 1626, and by Diego Fajardo Chacón in 1644. The erection of the Baluarte de San Diego was also completed that year, replacing the Nuestra Senora de Guia.[12] This bastion, shaped like an "ace of spades" is the southernmost point of the wall and the first of the large bastions added to the encircling walls, then of no great height nor of finished construction.[13] Ravelins and reductos were added to strengthen weak areas and serve as outer defenses. A moat was built around the city with the Pasig River serving as a natural barrier on one side. By the 18th century, the city was totally enclosed. The last construction works were completed by the start of the 19th century.[11]

Inside colonial Intramuros

The main square of the city of Manila was Plaza Mayor (later known as Plaza McKinley then Plaza de Roma) in front of the Manila Cathedral. East of the plaza was the Ayuntamiento (City Hall) and facing it was the Palacio del Gobernador, the official residence of the Spanish viceroyalties to the Philippines. An earthquake on June 3, 1863, destroyed the three buildings and much of the city. The residence of the Governor-General was moved to Malacañang Palace located about 3 km (1.9 mi) up on the Pasig River. The two previous buildings were later rebuilt but not the Governor's Palace.

Inside the walls were other Roman Catholic churches, the oldest being San Agustin Church (Augustinians) built in 1607. The other churches built by the different religious orders – San Nicolas de Tolentino Church (Recollects), San Francisco Church (Franciscans), Third Venerable Order Church (Third Order of St. Francis), Santo Domingo Church (Dominican), Lourdes Church (Capuchins), and the San Ignacio Church (Jesuits) – has made the small walled city the City of Churches. Intramuros was the center of large educational institutions in the Philippines.[3]

Convents and church-run schools were established by the different religious orders. The Dominicans established the Universidad de Santo Tomás in 1611 and the Colegio de San Juan de Letrán in 1620. The Jesuits established the Universidad de San Ignacio in 1590, the first university in the Philippines. It closed in 1768, following the expulsion of the Jesuits in the Philippines. After the Jesuits were allowed to return to the Philippines, they established the Ateneo Municipal de Manila in 1859.[14] In the initial period of colonization, there were a total of 1,200 Spanish families living in the vicinity of Intramuros, 600 Spanish families within the walls and another 600 living in the suburbs outside Intramuros. In addition to this were about 400 Spanish soldiers garrisoned at the walled city.[15]

American period (1898–1946)

After the end of the Spanish–American War, Spain surrendered the Philippines and several other territories to the United States as part of the terms of the Treaty of Paris for $20 million. The American flag was raised at Fort Santiago on August 13, 1898, indicating the start of American rule over the city. The Ayuntamiento became the seat of the Philippine Commission of the United States in 1901. Fort Santiago became the headquarters of the Philippine Division of the United States Army.

The Americans made drastic changes to Manila, such as in 1903, when the walls from the Santo Domingo Gate up to the Almacenes Gate were removed as the wharf on the southern bank of the Pasig River was improved. The stones removed were used for other construction happening around the city.

The walls were breached in four areas to ease access to the city: the southwestern end of Calle Aduana (now Andres Soriano Jr. Ave.); the eastern end of Calle Anda; the northeastern end of Calle Victoria (previously known as Calle de la Escuela); and the southeastern end of Calle Palacio (now General Luna Street). The double moats that surrounded Intramuros were deemed unsanitary and were filled in with mud dredged from Manila Bay, where the present Port of Manila is now located. The moats were transformed into a municipal golf course by the city.

Reclamations for the construction of the Port of Manila, the Manila Hotel, and Rizal Park obscured the old walls and skyline of the city from Manila Bay.[16] The Americans also founded the first school under the new government, the Manila High School, on June 11, 1906, along Victoria Street.[17]

In 1936, Commonwealth Act No. 171 was passed requiring that all future buildings to be constructed in Intramuros adopt Spanish colonial type architecture.

World War II and Japanese occupation

In December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army invaded the Philippines. The first casualties in Intramuros were the destruction of Santo Domingo Church and the original University of Santo Tomas campus during an assault. The whole city of Manila was declared by General Douglas MacArthur as an open city as Manila was indefensible.

In January 1945, the battle for the liberation of Manila began when American troops returned. Intense urban fighting occurred between the combined American and Filipino troops under the United States Army and Philippine Commonwealth Army including recognized guerrillas, against the 30,000 Japanese defenders. As the battle continued, both sides inflicted heavy damage on the city culminating with the Manila massacre by Japanese troops.[18]

The Imperial Japanese Army was pushed back, eventually retreating into the Intramuros district. General MacArthur, though opposed to the bombing of the walled city, approved heavy shelling, which resulted in deaths of over 16,665 Japanese within Intramuros.[18] Two of the eight gates of Intramuros were badly damaged by American tanks. The bombings levelled most of Intramuros, leaving only 5% of the city structures. 40% of the walls were destroyed in the bombings.[19][20] Over 100,000 Filipino men, women and children died from February 3 to March 3, 1945, during the Battle of Manila.

At the end of World War II, all of the buildings and structures in Intramuros were destroyed, with only the damaged San Agustin Church still standing.[20][21][22]

Contemporary period (1946–present)

In 1951, Intramuros was declared a historical monument and Fort Santiago, a national shrine with Republic Act 597, with the policy of restoring, reconstructing, and urban planning of Intramuros. In 1956, Republic Act 1607 declared Intramuros a "commercial, residential and educational district", opening up the district to development disregarding the historicity of the area. The same law also repealed Commonwealth Act No. 171 and Republic Act No. 597. Several laws and decrees also followed but results were deemed unsatisfactory due to limited funds.[23]

In 1979, the Intramuros Administration (IA) was created by virtue of Presidential Decree No. 1616, signed by President Ferdinand Marcos on April 10 of that year.[24]

Since then, the IA has been slowly restoring the walls, the sub-features of the fortification, and the city within. The remaining five original gates have been restored or rebuilt: Isabel II Gate, Parian Gate, Real Gate, Santa Lucía Gate and the Postigo Gate. The entrances made by the Americans by breaching the walls at four locations are now spanned by walkways thereby creating a connection, seamless in design and character to the original walls. Buildings destroyed during the war were subsequently rebuilt: Manila Cathedral was rebuilt and was opened to the public in 1958, Ayuntamiento de Manila was rebuilt in 2013, while the San Ignacio Church and Convent is currently being reconstructed as the Museo de Intramuros.

In January 2015, during Pope Francis's visit to the Philippines, he led a mass at the Manila Cathedral that was attended by an estimated 2,000 bishops, priests and religious leaders of the Philippine Catholic Church.[25] Anthology, an annual 3-day festival about architecture and design, was first launched in June 2016 at Intramuros. Since then, it has been renting Fort Santiago as a venue where seminars and other activities were held, with guest speakers from local and international people from the field of architecture and design.[26] It is made possible through the partnership of WTA Architecture + Design Studio and the Intramuros Administration, who are also responsible for the critically acclaimed the Book Stop Intramuros located in Plaza Roma.

The Department of Tourism along with the Intramuros Administration launched the first major project of the newly created Faith Sector that focuses on the historic and cultural religious wealth of the Walled City. For the 2018 lenten season, seven religious destinations can be visited. For the first time since World War II, Visita Iglesia is once again possible in Intramuros. The seven destinations are the Manila Cathedral, San Agustin Church, San Ignacio Church, Guadalupe Shrine in Fort Santiago, Knights of Columbus Fr. Willman Chapel, Lyceum of the Philippines University Chapel, and the Mapua University Chapel. The event pays homage to the original seven churches during the prewar Intramuros.[27][28] The 2018 lenten season event draws over 1 million people from both foreign and local tourists in Intramuros.[29][30] The Intramuros Administration, together with the Royal Danish Embassy in Manila, and Felta Multimedia, Inc., opened the iMake History Fortress at the Baluarte de Santa Barbara in Fort Santiago last March 19, 2018. The facility is the first history-based Lego education center in the world.[31]

The COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 caused the Intramuros Administration to temporarily close several sites within Intramuros including Fort Santiago, Museo de Intramuros, and Casa Manila.[32]

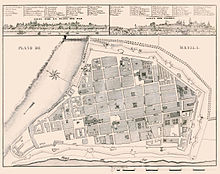

City walls

The stone outline of the defensive wall of Intramuros is irregular in shape, following the contours of Manila Bay and the curvature of the Pasig River. The Muralla walls covered an area of 64 hectares (160 acres) of land, surrounded by 8 feet (2.4 m) thick stones and high walls that rise to 22 feet (6.7 m). The walls stretched to an estimated 3-5 kilometers in length. An inner moat (foso) surrounds the perimeter of the wall and an outer moat (contrafoso) surrounds the walls that face the city.

Defense structures

Several bulwarks (baluarte), ravelins (ravellin) and redoubts (reductos) are strategically located along the massive walls of Intramuros following the design of medieval fortifications. The seven bastions (clockwise, from Fort Santiago) are the Bastions of Tenerias, Aduana, San Gabriel, San Lorenzo, San Andres, San Diego, and Plano.[33] The bastions were constructed at different periods of time, the reason for the differences in style. The oldest bastion is the Bastion de San Diego, which was built in 1587.

The fortifications of Intramuros comprises several parts, the front facing the sea and the river, which were less elaborate and complex, and the three-sided land front with its corresponding bastions. Fort Santiago was built at the northwest tip where the sea and river converge, and this functioned as a citadel. Fort Santiago has significantly served as military headquarters of Spanish, British, United States and Japan during different eras throughout the Philippine history.

In Fort Santiago, there are bastions on each corner of the triangular fort. The Baluarte de Santa Bárbara faces the bay and Pasig River; Baluarte de San Miguel, faces the bay; and the Medio Baluarte de San Francisco, which faces the Pasig River.[34]

Gates

Before the American Era, entrance to the city was through eight gates or Puertas. They were, clockwise, from Fort Santiago, Puerta Almacenes, Puerta de la Aduana, Puerta de Santo Domingo, Puerta Isabel II, Puerta del Parian, Puerta Real, Puerta Sta. Lucia, and Puerta del Postigo.[35] Three of the gates were destroyed. Two of them, the Almacenes Gate and the Santo Domingo/Customs Gate, were destroyed by American engineers when they open up the northern part of the walls to the wharves.[33]

The Banderas Gate was destroyed during an earthquake and was never rebuilt. Formerly, drawbridges were raised and the city was closed and under the watch of sentinels from 11:00 pm until 4:00 am. It continued so until 1852, when, in consequence of the earthquake of that year, it was decreed that the gates should remain open night and day.[33]

Present day Intramuros

Intramuros is the only district of Manila where old Spanish-era influences are still plentiful. Fort Santiago is now a well-maintained park and popular tourist destination. Adjacent to Fort Santiago is the reconstructed Maestranza Wall, which was removed by the Americans in 1903 to widen the wharves thus opening the city to Pasig River. One of the future plans of the Intramuros Administration is to complete the perimeter walls that surround the city making it completely circumnavigable from the walkway on top of the walls.[36]

There has been minimal commercialization occurring within the district, despite restoration efforts. A few fast food establishments set up shop at the turn of the 21st century, catering mostly to the student population within Intramuros. Shipping companies have also set up offices inside the district. Concerts, tours and exhibitions are frequently held within Intramuros to draw both local and foreign tourists.

Register of Styles

The Intramuros Register of Styles is the main architectural code of Intramuros, the historic core of the City of Manila, Philippines. It became part of Presidential Decree No. 1616, as amended, when it was gazetted by the Official Gazette of the Philippines on June 17, 2022.[37] The Intramuros Administration is the agency of the Philippine Government responsible for the implementation of the Register of Styles.

Intramuros in Manila is the only locality in the Philippines where, for cultural reasons, the use, height, scale, and aesthetics of all new constructions and development are pre-determined and strictly regulated under the force of a national law. The Register of Styles, as an integral part of Presidential Decree No. 1616, is the main legal document prescribing and guiding the implementation of pre-war architectural colonial styles in Intramuros.[38][39]

The Register of Styles is the first document to detail the historical styles of Intramuros. It was authored by Rancho Arcilla, who was then the Archivist of the Intramural Administration, and under the initiative of Guiller Asido, the former Administrator of Intramuros.[38] Being an integral part of Presidential Decree No. 1616, the Register of Styles is the only architectural stylebook in the Philippines with the force and potency of a national law.

By form, the urban landscape of Intramuros mostly lacked setbacks, with buildings that were mostly terraced (rowhouses). Courtyards or backyards were exceptionally well adapted to the climate. By style Intramuros was described as both vernacular and cosmopolitan. While its Church and State buildings were European in orientation, albeit adapted and localized, most of the buildings enclaved within its walls embraced tropical vernacular constructions as exemplified by the Bahay na bato. Churches, fortifications, and palaces fashioned in European styles, though few, became icons and objects of popular imagination. In contrast, the vernacular Bahay na Bato, which was adopted in majority of buildings, prevailed in terms of number of constructions. Except in certain instances, the Register of Styles prescribes tha Bahay na bato as the default style for new constructions in Intramuros.[39]

The Register of Styles prescribes the Bahay na bato as the default style for new constructions in Intramuros. It explicitly recognized the Bahay na Bato as the dominant architectural typology of Intramuros during the Spanish colonial era until the destruction of the Walled City in 1945 during the Second World War. Pursuant to the Intramuros Register of Styles, new constructions in Intramuros that do not follow the Bahay na Bato typology may only be allowed only in specific locations where a Non-Bahay na Bato structure (e.g. a Neoclassical building) was known to exist. Otherwise, new constructions are required to follow the Bahay na Bato type.[39]

Education

The center of education since the colonial period, Manila — particularly Intramuros — is home to several Philippine universities and colleges as well as its oldest ones. It served as the home of the University of Santo Tomas (1611), Colegio de San Juan de Letran (1620), Ateneo de Manila University (1859), Lyceum of the Philippines University and Mapúa University. The University of Santo Tomas transferred to a new campus at Sampaloc in 1927, and Ateneo left Intramuros for Loyola Heights, Quezon City (while still retaining "de Manila" in its name) in 1952.

New non-sectarian schools were established and built over the ruins after the war. The Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, established in 1965 by the city government of Manila, was built at the site of the old Cuartel España (Spanish Barracks). The Lyceum of the Philippines University, a private university founded in 1952 by Philippine President Jose P. Laurel, was built over the lot of San Juan de Dios Hospital. The hospital moved out to Roxas Boulevard in Pasay.

The Mapúa University, which was founded in 1925 in Quiapo, Manila moved in Intramuros after the war. Its postwar campus was built on the location of the destroyed San Francisco Church and the Third Venerable Order Church at the corner of San Francisco and Solana Streets. The three new educational institutions, along with Colegio de San Juan de Letran formed an academic cooperation called the Intramuros Consortium.

Churches

Intramuros, as the seat of religious and political power during the colonial period, was the home to eight grand churches built by different religious orders. All but one of these churches were destroyed in the Battle of Manila. Only San Agustin Church, the oldest building in existence in Manila completed in 1607, was the only structure inside the Walled City not to be destroyed during the war. The Manila Cathedral, the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila, was reconstructed in 1958.

The other religious orders reconstructed their churches outside Intramuros after the war. The Dominicans rebuilt Santo Domingo Church on Quezon Avenue in Quezon City. The Augustinian Recollects moved to their other church, the San Sebastian Church (now Basilica), 2.5-kilometer (1.6 mi) northeast of the Muralla, walled city. The Capuchins moved the Lourdes Church in 1951 to the corner of Kanlaon St. and Retiro St. (now Amoranto Ave.) in Quezon City. It was declared a National Shrine in 1997. The Order of Saint John of God moved to Roxas while the Order of Poor Clares in Aurora Boulevard. The San Ignacio Church and Convent is now currently being reconstructed as Museo de Intramuros, an ecclesiastical museum.

Monuments and statues

World War II, along with various disasters, has led to the destruction of numerous historical monuments and statues. However, several monuments have managed to withstand and the ones that remain can still be visited today in Intramuros. Other statues and monuments have been added as a testament to the area's rich history.

| Name | Image | Location | Designers | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolfo López Mateos Statue | Plaza Mexico 14°35′39″N 120°58′28″E / 14.59417°N 120.97444°E |

Luis A. Sanguino- Sculptor | Statue of a seated Adolfo López Mateos was the President of Mexico from 1958 to 1964. | ||

| Anda Monument |

|

Anda Circle | 1871 | Originally located at Plaza Maestranza near Fort Santiago. In 1957, the whole monument was transferred outside Intramuros to Bonifacio Drive, where it now stands in Anda Circle. In recent years it has been painted over, with the lower level vandalized with graffiti. | |

| Benavides Monument | Plaza Santo Tomas | Tony Noël | 1889 | Replica; the undamaged original statue was transferred in 1946 to the Sampaloc Campus of the University of Santo Tomas, now fronting the Main Building. Its original marble pedestal had been completely obliterated during the Battle of Manila in 1945. | |

| Carlos IV monument |

|

Plaza de Roma 14°35′32″N 120°58′23″E / 14.59222°N 120.97306°E |

Monument to Charles IV | ||

| King Philip II Statue |  |

Plaza de España 14°35′36″N 120°58′28″E / 14.59333°N 120.97444°E |

Monument to Philip II, where the Philippines is named after | ||

| Legazpi-Urdaneta Monument |

|

Bonifacio Drive opposite the Manila Hotel | Agustí Querol Subirats | 1929 | In 2012, some of its metal ornaments had been stolen and unscrupulously sold as scrap metal. |

| Memorare – Manila 1945 Memorial (Shrine of Freedom) |  |

Plazuela de Santa Isabel | 1995 | The inscription for the memorial was penned by National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin. | |

| Queen Isabel II Statue |

|

Puerta Isabel II | Ponciano Ponzano | 1860 | Formerly located at Plaza Rajah Sulayman in front of Malate Church. The statue was transferred in 1975 at the front of Puerta Isabel II during the visit of the then Prince Juan Carlos of Spain. |

| Rizal Statue |  |

Rizal Shrine | Depicts Jose Rizal, National Hero of the Philippines | ||

| Rizal sa loob ng piitan |  |

Rizal Shrine | Depicts Jose Rizal, National Hero of the Philippines |

Structures before and after World War II

| Structure | Image | Current structure | Image | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Churches | ||||

| Lourdes Church (1892-1945) |

|

El Amanecer Building |

|

|

| San Francisco Church (1739-1945) |

|

Mapúa University (Since 1956) |

|

|

| San Ignacio Church and Convent (1899-1945) |

|

Museo de Intramuros (Since 2018) |

|

The church and convent is being reconstructed as the Museo de Intramuros. |

| Recoletos Church (1739-1945) |

|

Manila Bulletin Headquarters |

|

|

| Santo Domingo Church (1868-1945) |

|

Bank of the Philippine Islands, Benlife Building, and Tuazon Building |

|

|

| Third Venerable Order Church (1733-1945) |

|

Mapúa University |

|

|

| Schools and Convents | ||||

| Ateneo de Manila University (1859-1932) |

|

Tent |

|

Transferred to its Padre Faura Campus (now Robinsons Manila) after a fire destroyed its Intramuros Campus in 1932. The school again transferred to its Loyola Heights Campus in 1976–77. |

| Beaterio de la Compania | Light and Sound Museum | Rebuilt as the Light and Sound Museum | ||

| Beaterio-Colegio de Santa Catalina | Colegio de San Juan de Letrán Campus |

|

The school and convent transferred to its new campus in Legarda Street, Sampaloc. Its Intramuros lot was acquired by the Colegio de San Juan de Letran to expand its postwar campus. | |

| Colegio de Santa Isabel (1632-1945) |

Vacant Lot, and Plazuela de Santa Isabel | Colegio de Santa Isabel transferred to its new postwar campus on Taft Avenue just outside the city walls. | ||

| Real Colegio de Santa Potenciana |

|

National Commission for Culture and the Arts, Philippine Red Cross (Manila Chapter), Philippine Veterans Building, and the Insurance Center Building | ||

| Santa Clara Monastery | Vacant Lot | |||

| University of Santo Tomas |

|

BF Condominiums |

|

UST transferred to its Sampaloc Campus in 1927. The College of Law remained at Intramuros. However, after the war, the university decided not to rebuild its Intramuros Campus. |

| Other Buildings | ||||

| Cuartel de España (Spanish Barracks) |

University of the City of Manila |

|

||

| Hospital de San Juan de Dios | Lyceum of the Philippines University |

|

||

| Palacio de Santa Potenciana | Philippine Red Cross |

|

||

Administration

Intramuros Administration

The Intramuros Administration (IA) is an agency of the Department of Tourism that is mandated to orderly restore, administer, and develop the historic walled area of Intramuros that is situated within the modern City of Manila as well as to insure that the 16th to 19th century Philippine-Spanish architecture remains the general architectural style of the walled area.[40] The Intramuros Administration oversee the day-to-day administration of the district, including the issuance of building permits, traffic re-routing, among others. Its office is located at Palacio del Gobernador in Plaza Roma.[41]

Barangays

Intramuros is composed of five barangays numbered 654 to 658. These five barangays only serve the welfare of the city's constituents because they neither have executive nor legislative powers.

Barangays 654, 655, and 656 are part of Zone 69 of the City of Manila, while barangays 657 and 658 are part of Zone 70.

| Zone | Barangay | Land area (km2) | Population (2020 census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 69 | Barangay 654 | 0.08678 km2 | 1,042 |

| Barangay 655 | 0.2001 km2 | 1,067 | |

| Barangay 656 | 0.3210 km2 | 364 | |

| Zone 70 | Barangay 657 | 0.3264 km2 | 982 |

| Barangay 658 | 0.2482 km2 | 2,108 |

See also

References

Citations

- ^ "2020 Census of Population and Housing Results" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. August 16, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Presidential Decree No. 1616 (April 10, 1979), Creating the "Intramuros Administration" for Purposes of Restoring and Administering the Development of Intramuros, The Official Gazette, retrieved July 12, 2017

- ^ a b Journal of American Folklore, Volumes 17-18. United States: American Folklore Society. 1904. p. 283. ISBN 1248746058. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ O'Connell, Daniel (1908). Manila, the Pearl of the Orient. Manila Merchants' Association. p. 20. ISBN 0217014798. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ "SCHOOLS - INTRAMUROS JOURNEY". discoverintramuros.weebly.com. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Sembrano, Edgar Allan M. (October 8, 2018). "Intramuros, Fort San Antonio Abad declared National Cultural Treasures". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ Pending Philippine UNESCO Nominations or Applications

- ^ a b Torres, Jose Victor (2005). Ciudad Murada, A Walk Through Historic Intramuros. Vibal Publishing House. p. 5. ISBN 971-07-2276-X.

- ^ a b U.S. War Department 1903, p. 435.

- ^ "Escolta Maestros: 6 Filipino architects who shaped the old CBD". April 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Torres, Jose Victor (2005). Ciudad Murada, A Walk Through Historic Intramuros. Vibal Publishing House. p. 6. ISBN 971-07-2276-X.

- ^ "Baluarte de San Diego". Intramuros, the Walled City. Retrieved on November 13, 2011.

- ^ U.S. War Department 1903, p. 436.

- ^ "History". Ateneo de Manila University. Retrieved on October 11, 2012.

- ^ Barrows, David (2014). "A History of the Philippines". Guttenburg Free Online E-books. 1: 179.

Within the walls, there were some six hundred houses of a private nature, most of them built of stone and tile, and an equal number outside in the suburbs, or "arrabales," all occupied by Spaniards ("todos son vivienda y poblacion de los Españoles"). This gives some twelve hundred Spanish families or establishments, exclusive of the religious, who in Manila numbered at least one hundred and fifty, the garrison, at certain times, about four hundred trained Spanish soldiers who had seen service in Holland and the Low Countries, and the official classes.

- ^ City of Manila. "Annual Report of the City of Manila, 1905", p.71. Manila Bureau of Printing.

- ^ "Manila High School" Archived August 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved on October 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Ramsey, Russell Wilcox (1993). "On Law & Country", pg. 41. Braden Publishing Company, Boston.

- ^ Esperanza Bunag Gatbonton. "A SHORT HISTORY AND GUIDE TO INTRAMUROS" (PDF). Philippine Academic Consortium for Latin American Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Sack of Manila". The Battling Bastards of Bataan (battlingbastardsbataan.com). Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ Bernad, Miguel A. "Genocide in Manila". California, USA: Philippine American Literary House (palhbooks.com). PALH Book. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ Quezon III, Manuel L. (February 7, 2007). "The Warsaw of Asia: How Manila was Flattened in WWII". Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Arab News Online (archive.arabnews.com). Opinion. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ "History of Intramuros". Intramuros, the Walled City. Retrieved on September 14, 2011.

- ^ "Presidential Decree no. 1616". The LawPhil Project. Retrieved on April 4, 2012.

- ^ Pedrasa, Ira (December 6, 2014). "Manila Cathedral: The basilica of popes". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ "Anthology: Stories About Architecture". WTA Architecture + Design Studio. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ Tantiangco, Aya (March 16, 2018). "Seven stops for Visita Iglesia in Intramuros open for the first time since WWII". GMA News. GMA News Online. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Rocamora, Joyce Ann L. (March 15, 2018). "3 big Lenten events lined up in Intramuros". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Arnaldo, Ma. Stella F. (April 3, 2018). "Intramuros welcomed 1 million Catholic faithful during Holy Week". BusinessMirror. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "Faith tourism: 1 million people visited Intramuros during Holy Week". ABS-CBN News. April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "iMake History Fortress LEGO Education Center opens in Intramuros". Intramuros Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ "Rizal Park, Intramuros sites temporarily closed amid COVID-19 spread". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c U.S. War Department 1903, p.443.

- ^ "Intramuros Walkthrough". Intramuros, the Walled City. Retrieved on October 1, 2011.

- ^ "IA Trivia - Eight main gates of Intramuros". Intramuros, the Walled City. Retrieved on September 14, 2011.

- ^ philstarcom (June 18, 2010). "Maestranza Wall Restoration". YouTube.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-18.

- ^ Intramuros Administration Website. Rules and Regulations in Intramuros May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Intramuros Register of Styles. Intramuros Register of Styles May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c Lawphil. Lawphil Intramuros Register of Styles May 1, 2023.

- ^ FY OPIF 2009 (PDF). Department of Budget and Management. 2009. p. 494. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "Contact Us". Intramuros Administration. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

Sources

- U.S. War Department (1903). "Annual Reports of the War Department, 1903 Vol. III". Washington Government Printing Office, 1901.

External links

- Intramuros Administration – Official website

Geographic data related to Intramuros at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Intramuros at OpenStreetMap