Ichthyostega

| Ichthyostega Temporal range: Late Devonian (Famennian), | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton in Moscow Paleontological Museum | |

| Skeletal reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Sarcopterygii |

| Clade: | Tetrapodomorpha |

| Clade: | Stegocephali |

| Family: | †Ichthyostegidae Säve-Söderbergh, 1932 |

| Genus: | †Ichthyostega Säve-Söderbergh, 1932 |

| Type species | |

| †Ichthyostega stensioei Säve-Söderbergh, 1932 | |

| Other species[1][2] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Genus synonymy

Species synonymy

| |

Ichthyostega (from Greek: ἰχθῦς ikhthûs, 'fish' and Greek: στέγη stégē, 'roof') is an extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian of what is now Greenland. It was among the earliest four-limbed vertebrates ever in the fossil record and was one of the first with weight-bearing adaptations for terrestrial locomotion. Ichthyostega possessed lungs and limbs that helped it navigate through shallow water in swamps. Although Ichthyostega is often labelled a 'tetrapod' because of its limbs and fingers, it evolved long before true crown group tetrapods and could more accurately be referred to as a stegocephalian or stem tetrapod. Likewise, while undoubtedly of amphibian build and habit, it is not a true member of the group in the narrow sense, as the first modern amphibians (members of the group Lissamphibia) appeared in the Triassic Period. Until finds of other early stegocephalians and closely related fishes in the late 20th century, Ichthyostega stood alone as a transitional fossil between fish and tetrapods, combining fish and tetrapod features. Newer research has shown that it had an unusual anatomy, functioning more akin to a seal than a salamander, as previously assumed.[3]

History

In 1932 Gunnar Säve-Söderbergh described four Ichthyostega species from the Late Devonian of East Greenland and one species belonging to the genus Ichthyostegopsis, I. wimani. These species could be synonymous (in which case only I. stensioei would remain), because their morphological differences are not very pronounced. The species differ in skull proportions, skull punctuation and skull bone patterns. The comparisons were done on 14 specimens collected in 1931 by the Danish East Greenland Expedition. Additional specimens were collected between 1933 and 1955.[4]

Description

Ichthyostega was a fairly large animal for its time, as it was broadly built and about 1.5 m (4.9 ft) long. The skull was low, with dorsally placed eyes and large labyrinthodont teeth. The posterior margin of the skull formed an operculum covering the gills. The spiracle was situated in an otic notch behind each eye. Computed tomography has revealed that Ichthyostega had a specialized ear, including a stapes with a unique morphology compared to other tetrapods or to any fish hyomandibula[5].

Postcranial skeleton

The legs were large compared to contemporary relatives. It had seven digits on each hind leg, along with a peculiar, poorly ossified mass which lies anteriorly adjacent to the digits.[6] The exact number of digits on the forelimb is not yet known, since fossils of the hand have not been found.[7] While in water, the foot would have functioned like a fleshy paddle more than a fin.[8]

The vertebral column and ribcage of Ichthyostega was unusual and highly specialized relative to both its contemporaries and later tetrapods. The thoracic vertebrae at the front of the trunk and the short neck have tall neural spines that lean backwards. They attach to pointed ribs which increase in size and acquire prominent overlapping flanges. Past the sixth or seventh flanged rib, the ribs abruptly decrease in size and lose their flanges. The lumbar vertebrae at the back of the trunk have strong muscle scars and neural spines which are bent forwards and decrease in size towards the hips. The sacral vertebrae above the hips have fan-shaped neural spines that transition from forward-leaning to backward-leaning as they approach the tail. The vertebrae right behind the hips have unusually large ribs similar to those of the thoracic region. The caudal vertebrae have slender spines that lean backwards.[8] The tail of Ichthyostega retained a low fin supported by bony lepidotrichia (fin rays). The tail fin was not as deep as in Acanthostega, and would have been less useful for swimming.[4]

Ichthyostega is related to Acanthostega gunnari, which is also from what is now East Greenland. Ichthyostega's skull seems more fish-like than that of Acanthostega, but its pelvic girdle morphology seems stronger and better adapted to life on land. Ichthyostega also had more supportive ribs and stronger vertebrae with more developed zygapophyses. Whether or not these traits were independently evolved in Ichthyostega is debated. It does, however, show that Ichthyostega may have ventured onto land on occasions, unlike contemporaneous limbed vertebrates, such as Elginerpeton and Obruchevichthys.[citation needed]

Classification

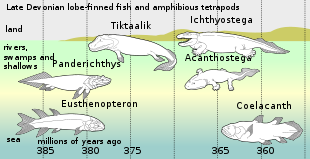

- Panderichthys, suited to muddy shallows;not on land

- Tiktaalik with limb-like fins that could take it onto land;

- Fully limbed vertebrates in weed-filled swamps, such as:

- Acanthostega which had feet with eight digits,

- Ichthyostega, with an oval-shaped neck and limbs.

Traditionally, Ichthyostega was considered part of an order named for it, the "Ichthyostegalia". However, this group represents a paraphyletic grade of primitive stem-tetrapods and is not used by many modern researchers. Phylogenetic analysis has shown Ichthyostega is intermediate between other primitive stegocephalian stem-tetrapods. The evolutionary tree of early stegocephalians below follows the results of one such analysis performed by Swartz in 2012.[9]

Paleobiology

Early limbed vertebrates like Ichthyostega and Acanthostega differed from earlier tetrapodomorphs such as Eusthenopteron or Panderichthys in their increased adaptations for life on land. Though tetrapodomorphs possessed lungs, they used gills as their primary means of discharging carbon dioxide. Tetrapodomorphs used their bodies and tails for locomotion and their fins for steering and braking; Ichthyostega may have used its forelimbs for locomotion on land and its tail for swimming.

Its massive ribcage was made up of overlapping ribs and the animal possessed a stronger skeletal structure, a largely fishlike spine, and forelimbs apparently powerful enough to pull the body from the water. These anatomical modifications may have evolved to handle the lack of buoyancy experienced on land. The hindlimbs were smaller than the forelimbs and unlikely to have borne full weight in an adult, while the broad, overlapping ribs would have inhibited side-to-side movements.[10] The forelimbs had the required range of movement to push the body up and forward, probably allowing the animal to drag itself across flat land by synchronous (rather than alternate) "crutching" movements, much like that of a mudskipper[3] or a seal.[11][12] It was incapable of typical quadrupedal gaits as the forelimbs lacked the necessary rotary motion range.[3]

See also

- Evolutionary history of life

- Hynerpeton

- List of transitional fossils

- List of prehistoric amphibians

- Ymeria

References

- ^ Haaramo, Mikko. "Taxonomic history of the genus †Ichthyostega Säve-Söderbergh, 1932". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive. Blom, 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ "Ichthyostega". Paleofile. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Stephanie E. Pierce; Jennifer A. Clack; John R. Hutchinson (2012). "Three-dimensional limb joint mobility in the early tetrapod Ichthyostega". Nature. 486 (7404): 524–527. Bibcode:2012Natur.486..523P. doi:10.1038/nature11124. PMID 22722854. S2CID 3127857.

- ^ a b Jarvik, Erik (15 April 1996). "The Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega" (PDF). Fossils and Strata. 40: 1–206. doi:10.18261/8200376605-1996-01. ISBN 8200376605.

- ^ Clack, J. A.; Ahlberg, P. E.; Finney, S. M.; Dominguez Alonso, P.; Robinson, J.; Ketcham, R. A. (2003). "A uniquely specialized ear in a very early tetrapod". Nature. 425 (6953): 65–69. doi:10.1038/nature01904. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Coates, M. I.; Clack, J. A. (1990). "Polydactyly in the earliest known tetrapod limbs". Nature. 347 (6288): 66–69. doi:10.1038/347066a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Evolutionary developmental biology, by Brian Keith Hall, 1998, ISBN 0-412-78580-3, p. 262

- ^ a b Ahlberg, Per Erik; Clack, Jennifer A.; Blom, Henning (2005). "The axial skeleton of the Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega". Nature. 437 (7055): 137–140. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..137A. doi:10.1038/nature03893. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 16136143. S2CID 4370488.

- ^ Swartz, B. (2012). "A marine stem-tetrapod from the Devonian of Western North America". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e33683. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...733683S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033683. PMC 3308997. PMID 22448265.

- ^ "Devonian Times – Tetrapods Answer". Archived from the original on 2021-07-26. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- ^ Williams, James J. (May 24, 2012). "Ichthyostega, one of the first creatures to step on land, could not have walked on four legs, say scientists". BelleNews. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ Mosher, Dave (May 23, 2012). "Evolutionary Flop: Early 4-Footed Land Animal Was No Walker?". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

Further reading

- Blom, H (2005). "Taxonomic Revision Of The Late Devonian Tetrapod Ichthyostega from East Greenland". Palaeontology. 48 (1): 111–134. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2004.00435.x.

- Westenberg, K (1999). "— From Fins to Feet". National Geographic. 195 (5): 114–127.

- Clack, J.A. (2012). Gaining ground: the origin and evolution of tetrapods (2nd ed.). Bloomington, Indiana, USA.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253356758.

External links

- Tree of Life Site on early tetrapods

- Getting a Leg Up on Land Scientific American Nov. 21, 2005, article by Jennifer A. Clack.

- BBC News: Ancient walking mystery deepens

- 3D computer model, forelimb maximal joint range, and hindlimb maximal joint range of Icthyostega on YouTube, videos by Stephanie E. Pierce, Jennifer A. Clack, & John R. Hutchinson