Henri, Count of Chambord

| Henri | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of Chambord Duke of Bordeaux | |||||

Photograph c. 1870 | |||||

| Legitimist pretender to the French throne as Henri V | |||||

| Pretence | 3 June 1844 – 24 August 1883 | ||||

| Predecessor | Louis XIX | ||||

| Successor | Philippe VII or Jean III | ||||

| Born | 29 September 1820 Tuileries Palace, Paris, France | ||||

| Died | 24 August 1883 (aged 62) Schloss Frohsdorf, Frohsdorf, Austria-Hungary | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Prince Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry | ||||

| Mother | Princess Maria Carolina of Naples and Sicily | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

Henri, Count of Chambord and Duke of Bordeaux (French: Henri Charles Ferdinand Marie Dieudonné d'Artois, duc de Bordeaux, comte de Chambord; 29 September 1820 – 24 August 1883)[1] was the Legitimist pretender to the throne of France as Henri V from 1844 until his death in 1883.

Henri was the only son of Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, born after his father's death, by his wife, Princess Carolina of Naples and Sicily, daughter of King Francis I of the Two Sicilies. The Duke himself was the younger son of Charles X. As the grandson of Charles X, Henri was a Petit-Fils de France. He was the last legitimate descendant of Louis XV of France in the male line.

Early life

Henri d'Artois was born on 29 September 1820, in the Pavillon de Marsan, a portion of the Tuileries Palace that still survives in the compound of the Louvre Palace in Paris. His father, the duc de Berry, had been assassinated seven months before Henri's birth.

At birth, Henri was given the title of duc de Bordeaux. Because of his birth after his father's death, when the senior male line of the House of Bourbon was on the verge of extinction, one of his middle names was Dieudonné (French for "God-given"). Royalists called him "the miracle child". Louis XVIII was overjoyed, bestowing 35 royal orders to mark the occasion. Henri's birth was a major setback for the Duke of Orleans' ambitions to ascend the French throne. During his customary visit to congratulate the newborn's mother, the duke made such offensive remarks about the baby's appearance that the lady holding him was brought to tears.[2]

Titular King

On 2 August 1830, in response to the July Revolution, Henri's grandfather, Charles X, abdicated, and twenty minutes later Charles' elder son Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême, himself renounced his rights, in favour of the young Duke of Bordeaux. Charles X urged his cousin Louis Philippe of Orléans, as Lieutenant général du royaume, to proclaim Henri as Henry V, King of France. Louis Philippe requested the Duke of Bordeaux to be brought to Paris to have his rights recognised. The duchess of Berry was forbidden to escort her son; therefore, both the grandfather and the mother refused to leave the child in France.[4] As a consequence, after seven days, a period in which legitimist monarchists considered that Henri had been the rightful monarch of France, the Chamber of Deputies decreed that the throne should pass to Louis Philippe, who was proclaimed King of the French on 9 August.[5]

Henri and his family left France and went into exile on 16 August 1830. While some French monarchists recognised him as their sovereign, others disputed the validity of the abdications of his grandfather and of his uncle.[citation needed] Still others recognised the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe. With the deaths of his 79-year-old grandfather in 1836 and of his uncle in 1844, young Henri became the genealogically senior claimant to the French throne. His supporters were called Legitimists, to distinguish them from the Orléanists, the supporters of the family of Louis Philippe.

Henri, who preferred the courtesy title of Count of Chambord (from the château de Chambord, which had been presented to him by the Restoration government, and which was the only significant piece of personal property of which he was allowed to retain ownership upon his exile), continued his claim to the throne throughout the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe, the Second Republic and Empire of Napoléon III, and the early years of the Third Republic.

In November 1846, the Count of Chambord married his second cousin Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria-Este, daughter of Duke Francis IV of Modena and Princess Maria Beatrice of Savoy. The couple had no children.

Hope of a restoration

In 1870, as the Second Empire collapsed following its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War at the battle of Sedan on 2 September 1870, the royalists became a majority in the National Assembly. The Orléanists agreed to support the Count of Chambord's claim to the throne, with the expectation that upon his death, with him lacking any sons, he would be succeeded by their own claimant, Philippe d'Orléans, Count of Paris. With Henri backed by both Legitimists and Orléanists, the restoration of monarchy in France seemed a likely possibility. However, he insisted that he would accept the crown only on condition that France abandon its tricolour flag (associated with the French Revolution) and return to the use of the fleur de lys flag,[7] comprising the historic royal arms of France. He rejected a compromise whereby the fleur-de-lys would be the new king's personal standard, and the tricolour would remain the national flag. Pope Pius IX, upon hearing Henri's decision, notably remarked "And all that, all that for a napkin!"[8]

In 1873 another attempt to restore the monarchy failed for the same reasons. Henri traveled to Paris and tried to negotiate with the government, to no avail; and on 20 November, the National Assembly confirmed Marshal The 1st Duke of Magenta as Chief of State of France for the next seven years.[9]

Defeat

The Third Republic was established (with then Chief of State, the Duke of Magenta, as President of the Republic) to wait for Henri's death and his replacement by his distant cousin, the more liberal Count of Paris, of the Orléanist branch of the House of Bourbon. Initially, the monarchist majority in Parliament believed this to be temporary, until such time as the Count of Paris could return to the throne. However, by the time this occurred in 1883, public opinion had swung behind the Republic as the form of government which, in the words of the former President Adolphe Thiers, "divides us least". Thus, Henri could mockingly be hailed by republicans such as Georges Clemenceau as "the French Washington" – the one man without whom the Republic could not have been founded.

Henri died on 24 August 1883 at his residence in Frohsdorf, Austria, at the age of 62, bringing the male line of Louis XV to an end. He was buried in the crypt of his grandfather Charles X, in the church of the Franciscan Kostanjevica Monastery in Gorizia, Austria (now Slovenia). His personal property, including the Château de Chambord, was left to his nephew Robert I, Duke of Parma, son of Henri's late sister.

Henri's death left the Legitimist line of succession distinctly confused. On the one hand, Henri himself had accepted that the head of the House of France (as distinguished from the House of Bourbon) would be the head of the Orléans line, i.e. Prince Philippe, Count of Paris. This was accepted by many Legitimists, and was the default on legal grounds; the only surviving Bourbon male line more senior was the branch of the Kings of Spain, descended from King Philip V, which had however renounced its right to inherit the throne of France as a condition of the Treaty of Utrecht. However, several of Henri's supporters, including his widow, chose to disregard his statements and the Treaty, arguing that no one had the right to deny that the senior direct male-line Bourbon was the head of the House of France and thus the legitimate King of France; the renunciation of the Spanish branch would be, under this interpretation, illegitimate and therefore void. Thus the Blancs d'Espagne, as they would come to be known, settled on Infante Juan, Count of Montizón, the former Carlist pretender to the Spanish throne,[10] as their claimant to the French crown.

Gallery

- The Duchess of Berry and her children by François Gérard, 1822

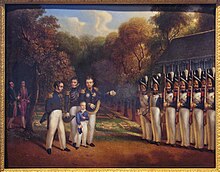

- The young Duke of Bordeaux in a military uniform, by Alexandre-Jean Dubois-Drahonet, 1828

- The Duchess of Berry and her son by François Gérard, 1828

- Detail of portrait, c. 1830

- Portrait, c. 1833

Honours

House of Bourbon: Grand Master and Grand Croix of the Order of the Holy Spirit

House of Bourbon: Grand Master and Grand Croix of the Order of the Holy Spirit Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (1823)[11]

Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (1823)[11]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Henri, Count of Chambord |

|---|

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 822–823.

- ^ Bernard, J.F. (1973). Talleyrand: A Biography. New York: Putnam. p. 495. ISBN 0-399-11022-4.

- ^ Castelot, André (1988). Charles X. Paris: Perrin. p. 492. ISBN 978-2-262-00545-0.

- ^ Garnier, J. (1968). "Louis-Philippe et le Duc de Bordeaux (avec des documents inédits)". Revue Des Deux Mondes (1829–1971), 38–52. Retrieved May 26, 2020. JSTOR 44593301

- ^ Price, Munro (2007). The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions. London: Macmillan. pp. 177, 181–182, 185. ISBN 978-1-4050-4082-2.

- ^ Smith, Whitney (1975). Flags: Through the Ages and Across the World. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-07-059093-9.

- ^ D. W. Brogan, The Development of Modern France (1870–1939) (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1945), pp. 83–84.

- ^ "The Humour of Pope Pius IX". EWTN.

- ^ Gabriel de Broglie, Mac Mahon, Paris, Perrin, 2000, pp. 247–251.

- ^ The Semi-Salic law of succession instituted by Philip V in 1713 had been suspended in Spain by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830. Therefore, the actual king of Spain, Alfonso XII, was not the senior descendant of Hugh Capet in the male line.

- ^ "Toison Espagnole (Spanish Fleece) – 19th century" (in French), Chevaliers de la Toison D'or. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

Further reading

- Brown, Marvin Luther. The Comte de Chambord :The Third Republic's Uncompromising King. Durham, N.C.:, Duke University Press, 1967.

- Delorme, Philippe. Henri, comte de Chambord, Journal (1846–1883), Carnets inédits. Paris: Guibert, 2009.

- Lucien Edward Henry (1882). "The Royal Family of France". The Royal Family of France: 49–51. Wikidata Q107258956.

- "The Death of the comte de Chambord", British Medical Journal 2, no. 1186 (September 22, 1883): 600–601.