Helical scan

Helical recording method. As the tape moves horizontally, the drum rotates and the heads in the drum create or write diagonal tracks with signals. | |

| Media type | magnetic tape |

|---|---|

| Usage | recording high-frequency signals |

Helical scan is a method of recording high-frequency signals on magnetic tape, used in open-reel video tape recorders, video cassette recorders, digital audio tape recorders, and some computer tape drives.

With this technique, magnetic tape heads (or head chips) are placed on a rotating head drum,[1] which moves the chips at high speed by due to its high angular velocity. The speed of the head chips must be higher than the linear speed of the tape. The tape is wrapped tightly around the drum. The drum[2] and/or the tape is tilted at an angle that allows the head chips to read the tape diagonally. The linear speed of the tape is slower than the speed of the head chips, allowing high frequency signals to be read or recorded, such as video. As the tape moves linearly or length-wise, the head chips move across the width of the tape in a diagonal path. Due to geometry, this allows for high head chip speeds, known as writing speeds, to be achieved in spite of the low linear speed of the tape. The high writing speed allows for high frequency signals to be recorded.[3][4][5] As each head chip enters into contact with the tape, it creates or reads long and narrow areas with information recorded magnetically known as tracks. In Helical scan, these tracks are positioned diagonally, relative to the length of the tape. The diagonal tracks read or written using this method are known as helical tracks.[2]

Types

There are several types of helical scan. These include:

- Alpha wrap (α), in which the tape is wrapped around the drum in a full, 360 degree fashion.[6][7]

- Omega wrap (Ω), in which the tape is wrapped almost fully around the drum similar to the Greek letter Omega. Used in Type-C videotape recorders. The tape is wrapped 346 degrees around the drum with 270 degrees used for recording. Because of this, the vertical blanking interval of the video signal is lost and to prevent this a secondary head in a "1 1/2 head" configuration must record the interval when the video head is not reading the tape. A full frame of video with two fields can be recorded in a single revolution of the drum with a single head creating a single diagonal track on the tape.[8][9][10][11]

- C wrap, where the tape is wrapped around the head drum in the shape of a backwards C, used in the Betacam format, uses a wrap of 200 to 300 degrees where 180 to 270 degrees are active or used for recording, similar to the U wrap which is reminiscent of an U laid on its side and is used in the U-matic format. Because the tape is not wrapped around the drum as much as with the omega wrap, two heads creating two diagonal tracks must be used to record a video frame, one field for every track and head.[12][13][10][14]

- M wrap, used in VHS and the D-1 (Sony) and D-2 (video) digital videotape formats, wraps the tape around the head drum in a pattern or in a tape path reminiscent of the letter M, around the left and right side of the head drum, 250 to 300 degrees around it where 180 to 270 degrees are active or used for recording, with two heads if 180 degrees are used.[15][16][10][17]

- Half wrap, used to denominate any type of wrap where the tape covers approximately 180 degrees, or half of the circumference of the drum. To record a full frame of video it requires at least two video heads, each recording a video field, of which two are necessary to record a video frame.[18][19]

Many helical scan cassette formats such as VHS and Betacam use a head drum with heads that use azimuth recording, in which the heads in the head drum have a gap that is tilted at an angle, and opposing heads have their gaps tilted so as to oppose each other.[20][21] This eliminates the need for guard bands between the helical tracks allowing for a higher density of information on the tape.[22][23][24]

History

Earl Edgar Masterson from RCA patented the first helical scan method in 1950.[25][26] German engineer Eduard Schüller developed a helical scan method of recording in 1953 while working at AEG.[27][28] With the advent of television broadcasting in Japan in the early 1950s, they saw the need for magnetic television signal recording. Dr. Kenichi Sawazaki developed a prototype helical scan recorder in 1954.[29] Helical scan machines were demonstrated by Toshiba in 1959 and since they recorded one field of video per track, they were the first to allow video to be paused and played back at speeds other than real time. Helical scan type B and type C videotape began to be used in 1976.[30]

Gallery

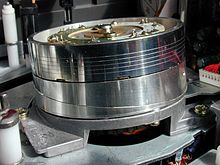

- Type B videotape video scanner head

- Rotary head visible in a VXA computer tape drive

- VXA tape drive, alternate view of rotary head and loading mechanism

See also

- Azimuth recording, used in many helical scan video formats

- Type A videotape

- 1 inch type B videotape

- 1 inch type C videotape

- IVC videotape format about the IVC 2-inch helical VTR, Model 9000

- Video tape recorder (VTR)

- Vision Electronic Recording Apparatus

- Ampex 2 inch helical VTR

- Symmetric Phase Recording

References

- ^ "Rotary magnetic head drum with fluid bearing and with head chips mounted together in parallel".

- ^ a b Tozer, E. P. J. (November 12, 2012). Broadcast Engineer's Reference Book. CRC Press. ISBN 9781136024184 – via Google Books.

- ^ Capelo, Gregory; Brenner, Robert C. (June 26, 1998). VCR Troubleshooting and Repair. Newnes. ISBN 9780750699402 – via Google Books.

- ^ Daniel, Eric D.; Mee, C. Denis; Clark, Mark H. (August 31, 1998). Magnetic Recording: The First 100 Years. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780780347090 – via Google Books.

- ^ "New Scientist". Reed Business Information. December 1, 1983 – via Google Books.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Abramson, Albert (September 15, 2007). The History of Television, 1942 to 2000. McFarland. ISBN 9780786432431 – via Google Books.

- ^ Watkinson, John (April 17, 1996). Television Fundamentals. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136027543 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gulati, R. R. (December 2005). Monochrome and Colour Television. New Age International. ISBN 978-81-224-1776-0.

- ^ Daniel, Eric D.; Mee, C. Denis; Clark, Mark H. (August 31, 1998). Magnetic Recording: The First 100 Years. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780780347090 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Tozer, E. P. J. (November 12, 2012). Broadcast Engineer's Reference Book. CRC Press. ISBN 9781136024184 – via Google Books.

- ^ Magnetic Recording Handbook. Springer Science & Business Media. December 6, 2012. ISBN 9789401094689 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mellor, David (July 18, 2013). Sound Person's Guide to Video. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136120787 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brenner, Robert; Capelo, Gregory (August 26, 1998). VCR Troubleshooting and Repair. Elsevier. ISBN 9780080520476 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jackson, K. G.; Townsend, G. B. (2014-05-15). TV & Video Engineer's Reference Book. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-9375-5.

- ^ Brenner, Robert; Capelo, Gregory (August 26, 1998). VCR Troubleshooting and Repair. Elsevier. ISBN 9780080520476 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brenner, Robert; Capelo, Gregory (August 26, 1998). VCR Troubleshooting and Repair. Elsevier. ISBN 9780080520476 – via Google Books.

- ^ Trundle, Eugene (June 11, 2001). Newnes Guide to Television and Video Technology. Newnes. ISBN 9780750648103 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bali, S. P. Bali, Rajeev. "Audio Video Systems". Khanna Publishing House – via Google Books.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mellor, David (July 18, 2013). Sound Person's Guide to Video. Taylor & Francis. p. 24. ISBN 9781136120787 – via Google Books.

- ^ Goldwasser, Sam (January 2000). "VCRs". Poptronics. Vol. 1, no. 1. pp. 77–79. ISSN 1526-3681.

- ^ Tozer, E. P. J. (November 12, 2012). Broadcast Engineer's Reference Book. CRC Press. ISBN 9781136024184 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tozer, E. P. J. (November 12, 2012). Broadcast Engineer's Reference Book. CRC Press. ISBN 9781136024184 – via Google Books.

- ^ Capelo, Gregory; Brenner, Robert C. (June 26, 1998). VCR Troubleshooting and Repair. Newnes. ISBN 9780750699402 – via Google Books.

- ^ Trundle, Eugene (May 12, 2014). Newnes Guide to TV and Video Technology. Elsevier. ISBN 9781483183169 – via Google Books.

- ^ Patent US2773120

- ^ "Magnetic Videotape Recording". April 2019.

- ^ SMPTE Journal: Publication of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, Volume 96, Issues 1-6; Volume 96, page 256, Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers

- ^ "Schüller, Eduard - Deutsche Biographie". www.deutsche-biographie.de (in German). Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ "Toshiba Science Museum : World's First Helical Scan Video Tape Recorder". toshiba-mirai-kagakukan.jp. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Montaña, Ricardo Cedeño (August 21, 2017). Portable Moving Images: A Media History of Storage Formats. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9783110553925 – via Google Books.

External links

- Sony U.S. patent for U-matic videotape cassette, filed 1971.

- Sony U.S. patent for design of U-matic deck, filed 1971.

- Video Preservation Equipment Museum

- The History of Television, 1942 to 2000, by Albert Abramson, page 93.

- Ampex page in the Experimental TV Center