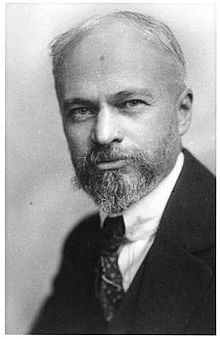

Harrison Gray Dyar Jr.

Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 14, 1866 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | January 21, 1929 (aged 62) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (B.S.) Columbia University (M.A.) Columbia University (Ph.D.) |

| Years active | 1889–1929 |

| Known for | Scientist, entomologist |

| Parent(s) | Harrison Gray Dyar, Eleonora Rosella Hunt |

| Relatives | Harrison Gray Otis (second cousin) |

Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. (February 14, 1866 – January 21, 1929) was an American entomologist. Dyar's Law, a pattern of geometric progression in the growth of insect parts, is named after him. He was also noted for eccentric pursuits which included digging tunnels under his home. He had a complicated personal life and along with his second wife he adopted the Baháʼí Faith.

Early life

Dyar was born in Linwood Hill, Rhinebeck, New York, to Harrison Gray Dyar and his wife Eleonora Rosella (née Hannum).[1][2] His father made a fortune as a chemist and inventor, and upon his death in 1875, left Dyar and the family financially independent.[3] He wrote ghost stories for his sister Perle while his mother took a keen interest in spiritualism. The household also included Lucy Hudson, a homeopath who had a relative, George Henry Hudson (1855-1934) who inculcated Dyar with an interest in natural history. He also learned music and playing the piano from the Hudson family.

In 1880 the family moved to Boston and he attended Roxbury Latin School. Dyar went to DeGarmo Institute around 1882, founded by James M. DeGarmo who also maintained a large collection of butterflies. Dyar passed the entrance to Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and chose the latter. He graduated from MIT in 1889 with a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry. He had begun to study insects as a young teenager,[1][4] and soon after his graduation from college began publishing scientific papers about them, in particular moths of the family Limacodidae,[1] starting a lifelong interest in entomology.

He joined a course in embryology at the Woods Hole Biological Station in 1893,[5] and subsequently Columbia University where he trained under Henry Fairfield Osborn, and where he was influenced in eugenics. He was awarded a Master of Arts degree in biology from Columbia University in 1894, with his thesis on the classification of Lepidoptera, and a doctorate in 1895, with his dissertation on airborne bacteria in New York City under the supervision of Theophil Mitchell Prudden.[1][6] He was also encouraged by his sister Perle's husband S. Adophus Knopf as careers in insect taxonomy were rare. After his PhD he worked on the classification of Lepidoptera based on caterpillar morphology.

Taxonomy

Dyar's lepidoptera collecting brought him in contact with Ferdinand Heinrich Herman Strecker and the Boston Society of Natural History where he was in contact with Joseph Albert Lintner and Charles H. Fernald. Dyar's early studies involved rearing caterpillars. After his major field collecting trips he began to work more intently as a taxonomist and published extensively on moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera).

Dyar's most notable work was on the number of molts of larvae published in Psyche in 1890. Dyar's Law, the biological rule named for him in recognition of his original observations on the geometric progression in head capsule widths during the larval development of Lepidoptera, is a standard approach for identifying the stage of immature insects or to predict the number of molts.[1] His training in maths and chemistry made him organize the information in a tabular form.[7] An earlier publication in 1886 by W.K. Brooks independently described the same phenomenon in crustaceans,[8][9] and therefore the term "Brooks-Dyar Law" (or "Brooks Rule" or "Brooks-Dyar Rule") also commonly appears in the literature.[10]

His first job was as assistant bacteriologist of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University from 1895 to 1897.[6] From 1897 until his death he was honorary custodian of Lepidoptera at the U.S. National Museum, Washington, D.C.[6] The position, though unsalaried, had been made possible by Leland Ossian Howard. He collaborated with Emily L. Morton to describe the life-histories of north American Limacodidae. His later studies were mainly on mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae), and sawflies (Hymenoptera: Symphyta).[6] Dyar was independently wealthy and for a major part of his 31 years at the USNM he worked without compensation; his independence also made it possible for him to travel and collect extensively within North America.[6]

Dyar was editor of the Journal of the New York Entomological Society from 1904 to 1907 and of the Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington from 1909 to 1912; from 1913 to 1926 he published and edited his own taxonomic journal, Insecutor Inscitiae Menstruus.[6] Dyar and Frederick Knab were primarily responsible for the taxonomic portions of The Mosquitoes of North and Central America and the West Indies, published, with co-author L. O. Howard, in four volumes from 1912–1917.[6]

Dyar was also noted for his intellectual and at times acerbic exchanges with fellow entomologists, for example, in correspondence with Clara Southmayd Ludlow,[11] he engaged in a "protracted, spectacularly belligerent feud with fellow entomologists".[12] Another feud was with John Bernhardt Smith who was not careful in his application of taxonomic principles. A myth was born from the feud with Smith that the latter had named a genus of moth as Dyaria (to pun with diarrhoea). The genus was in fact erected by Dyar's friend, the amateur entomologist Berthold Neumoegen and was not in any way derogatory.[13][14]

In 1924, Dyar was commissioned a captain in the Sanitary Department of the U.S. Army Reserve Officers Corps because of his background in the study of mosquitoes.[15]

Personal life

Dyar married Zella M. Peabody of Los Angeles, a music teacher in 1889. They had two children.[1] He went on a "collecting honeymoon" for fifteen months with his wife around the country, making long trips by train and collecting insects from various localities. Dyar was discovered later to be a bigamist, "for fourteen years he was married to two women, maintaining two families with five children in all."[1][12] His marriage to Peabody ended in 1920.[12] But in 1906, using the alias of Wilfred P. Allen, Dyar had married Wellesca Pollock.[12] In 1921, now divorced from Peabody, Dyar legally married Pollock; they had three sons.[1]

Pollock was an educator and ardent disciple of the Baháʼí Faith.[1] After his legal marriage to Pollock, Dyar became active in the Baháʼí Faith, and edited an independent Baháʼí journal, Reality, from 1922 until his death.[1]

During the 1920s, Dyar's hobby of tunnel building was discovered when a truck broke through into a labyrinth of tunnels near his former home at 1512 21st Street NW in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C.[1][2][12][16]

Dyar was a second cousin of American Civil War soldier and publisher Harrison Gray Otis.[17]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pamela M. Henson: Dyar, Harrison Gray Jr., Baháʼí Library Online, http://bahai-library.com/henson_harrison_dyar. Retrieved Nov 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Marc E. Epstein and Pamela M. Henson. 1992. Digging for Dyar, The Man Behind the Myth. American Entomologist 38:148–169.

- ^ Mallis 1971 p. 324

- ^ Frank E. Dyer: Dyer Families of New England, Descendants of Thomas Dyer of Weymouth, Mass, http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~dyer/. Retrieved Nov 5, 2010.

- ^ Epstein:34-35.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kenneth L. Knight & Ruth B. Pugh. 1974. A Bibliography of Mosquito Writings of H. G. Dyar and Frederick Knab. Mosquito Systematics 6(1): 11–26.

- ^ Epstein:21-25.

- ^ Brooks WK 1886. Report on the Stomatopoda collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76. In: The voyage of H.M.S. Challenger, report 45, vol.16

- ^ Crosby, T.K. 1973 Dyar's rule predated by Brooks' rule. New Zealand Entomologist: 5 (2):175-176

- ^ Daly, H.V. 1985 Insect morphometrics. Annual Review of Entomology 30: 415-438

- ^ Ronald R. Ward. 1987. Biography of Clara Southmayd Ludlow 1852–1924. Mosquito Systematics 19(3): 251–258, edited reprinting of information first published by James B. Kitzmiller: Anopheline Names, Their Derivations and Histories, The Thomas Say Foundation, Vol. VIII, 1982, pp. 316–321.

- ^ a b c d e Foster, William (January 14, 2016). Campbell, Philip (ed.). "A life of insects and ire". Nature. 529 (7585). London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd.: 152–3. doi:10.1038/529152a. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Neumoegen, B. (1893). "Description of a peculiar new Liparid genus from Maine". Canadian Entomologist. 25 (9): 213–215. doi:10.4039/S0008347X00177776.

- ^ Epstein:36-37.

- ^ Terry L. Carpenter and Terry A. Klein. 2011. 2011 AMCA Memorial Lecture Honoree: Dr. Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 27(3):336–343.

- ^ ghostsofdc (November 9, 2023). "Harrison Dyar: The Scientist Who Dug Secret Tunnels Under D.C." Ghosts of DC. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ Harrison Gray Dyar Jr.: A Preliminary Genealogy of the Dyar Family, Gibson Bros., Printers, Washington, D.C., 1903, p. 16.

Further reading

- Epstein, Marc (2016). Moths, Myths, and Mosquitoes: The Eccentric Life of Harrison Dyar Jr. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190215279.

- Mallis, Arnold (1971). American Entomologists. Rutgers University Press. pp. 323–326.

External links

- "Tunnel Digging as a Hobby" Archived February 18, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Modern Mechanix (1932) featuring a diagram of one of Dyar's tunnels

- The Bizarre Tale of the Tunnels, Trysts and Taxa of a Smithsonian Entomologist