Furniture

Furniture refers to objects intended to support various human activities such as seating (e.g., stools, chairs, and sofas), eating (tables), storing items, working, and sleeping (e.g., beds and hammocks). Furniture is also used to hold objects at a convenient height for work (as horizontal surfaces above the ground, such as tables and desks), or to store things (e.g., cupboards, shelves, and drawers). Furniture can be a product of design and can be considered a form of decorative art. In addition to furniture's functional role, it can serve a symbolic or religious purpose. It can be made from a vast multitude of materials, including metal, plastic, and wood. Furniture can be made using a variety of woodworking joints which often reflects the local culture.

People have been using natural objects, such as tree stumps, rocks and moss, as furniture since the beginning of human civilization and continues today in some households/campsites. Archaeological research shows that from around 30,000 years ago, people started to construct and carve their own furniture, using wood, stone, and animal bones. Early furniture from this period is known from artwork such as a Venus figurine found in Russia, depicting the goddess on a throne. The first surviving extant furniture is in the homes of Skara Brae in Scotland, and includes cupboards, dressers and beds all constructed from stone. Complex construction techniques such as joinery began in the early dynastic period of ancient Egypt. This era saw constructed wooden pieces, including stools and tables, sometimes decorated with valuable metals or ivory. The evolution of furniture design continued in ancient Greece and ancient Rome, with thrones being commonplace as well as the klinai, multipurpose couches used for relaxing, eating, and sleeping. The furniture of the Middle Ages was usually heavy, oak, and ornamented. Furniture design expanded during the Italian Renaissance of the fourteenth and fifteenth century. The seventeenth century, in both Southern and Northern Europe, was characterized by opulent, often gilded Baroque designs. The nineteenth century is usually defined by revival styles. The first three-quarters of the twentieth century are often seen as the march towards Modernism. One unique outgrowth of post-modern furniture design is a return to natural shapes and textures.[1]

Etymology

The English word furniture is derived from the French word fourniture,[2] the noun form of fournir, which means to supply or provide.[3] Thus fourniture in French means supplies or provisions.[4] The English usage, referring specifically to household objects, is specific to that language;[5] French and other Romance languages as well as German use variants of the word meubles, which derives from Latin mobilia, meaning "moveable goods".[6]

History

Prehistory

The practice of using natural objects as rudimentary pieces of furniture likely dates to the beginning of human civilization.[7] Early humans are likely to have used tree stumps as seats, rocks as rudimentary tables, and mossy areas for sleeping.[7] During the late Paleolithic or early Neolithic period, from around 30,000 years ago, people began constructing and carving their own furniture, using wood, stone and animal bones.[8] The earliest evidence for the existence of constructed furniture is a Venus figurine found at the Gagarino site in Russia, which depicts the goddess in a sitting position, on a throne.[9] A similar statue of a seated woman was found in Çatalhöyük in Turkey, dating to between 6000 and 5500 BCE.[7] The inclusion of such a seat in the figurines implies that these were already common artefacts of that age.[9]

A range of unique stone furniture has been excavated in Skara Brae, a Neolithic village in Orkney, Scotland The site dates from 3100 to 2500 BCE and due to a shortage of wood in Orkney, the people of Skara Brae were forced to build with stone, a readily available material that could be worked easily and turned into items for use within the household. Each house shows a high degree of sophistication and was equipped with an extensive assortment of stone furniture, ranging from cupboards, dressers, and beds to shelves, stone seats, and limpet tanks. The stone dresser was regarded as the most important as it symbolically faces the entrance in each house and is therefore the first item seen when entering, perhaps displaying symbolic objects, including decorative artwork such as several Neolithic carved stone balls also found at the site.

- The Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük, a figurine discovered in Turkey and dated to approximately 6000 BC, is evidence that furniture already existed by that point.

- A dresser with shelves furnishes a house in Skara Brae, a settlement in what is now Scotland that was occupied from about 3180–2500 BC

- Cucuteni ritualic figurines sitting on miniature chairs; 4900–4750 BC; painted ceramic; Archaeology Museum Piatra Neamț (Piatra Neamț, Romania)

- Cucuteni figurine staying on a miniature chair; 4750–4700 BC; ceramic; discovered at Târpești (modern-day Romania); Archaeology Museum Piatra Neamț

Antiquity

Ancient furniture has been excavated from the 8th-century BCE Phrygian tumulus, the Midas Mound, in Gordion, Turkey. Pieces found here include tables and inlaid serving stands. There are also surviving works from the 9th–8th-century BCE Assyrian palace of Nimrud. The earliest surviving carpet, the Pazyryk Carpet was discovered in a frozen tomb in Siberia and has been dated between the 6th and 3rd century BCE.

Ancient Egypt

Civilization in ancient Egypt began with the clearance and irrigation of land along the banks of the River Nile,[10] which began in about 6000 BCE. By that time, society in the Nile Valley was already engaged in organized agriculture and the construction of large buildings.[11] At this period, Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and also constructing large buildings. Mortar was in use by around 4000 BCE The inhabitants of the Nile Valley and delta were self-sufficient and were raising barley and emmer (an early variety of wheat) and stored it in pits lined with reed mats.[12] They raised cattle, goats and pigs and they wove linens and baskets.[12] Evidence of furniture from the predynastic period is scarce, but samples from First Dynasty tombs indicate an already advanced use of furnishings in the houses of the age.[13]

During the Dynastic Period, which began in around 3200 BCE, Egyptian art developed significantly, and this included furniture design.[14] Egyptian furniture was primarily constructed using wood, but other materials were sometimes used, such as leather,[15] and pieces were often adorned with gold, silver, ivory and ebony, for decoration.[15] Wood found in Egypt was not suitable for furniture construction, so it had to be imported into the country from other places,[14] particularly Phoenicia.[16] The scarcity of wood necessitated innovation in construction techniques. The use of scarf joints to join two shorter pieces together and form a longer beam was one example of this,[17] as well as construction of veneers in which low quality cheap wood was used as the main building material, with a thin layer of expensive wood on the surface.[18]

The earliest used seating furniture in the dynastic period was the stool, which was used throughout Egyptian society, from the royal family down to ordinary citizens.[19] Various different designs were used, including stools with four vertical legs, and others with crossed splayed legs; almost all had rectangular seats, however.[19] Examples include the workman's stool, a simple three legged structure with a concave seat, designed for comfort during labour,[20] and the much more ornate folding stool, with crossed folding legs,[21] which were decorated with carved duck heads and ivory,[21] and had hinges made of bronze.[19] Full chairs were much rarer in early Egypt, being limited to only wealthy and high ranking people, and seen as a status symbol; they did not reach ordinary households until the 18th dynasty.[22] Early examples were formed by adding a straight back to a stool, while later chairs had an inclined back.[22] Other furniture types in ancient Egypt include tables, which are heavily represented in art, but almost nonexistent as preserved items – perhaps because they were placed outside tombs rather than within,[23] as well as beds and storage chests.[24][25]

- Stool with woven seat; 1991–1450 BC; wood & reed; height: 13 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Jewelry chest of Sithathoryunet; 1887–1813 BC; ebony, ivory, gold, carnelian, blue faience and silver; height: 36.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Chair of Hatnefer; 1492–1473 BC; boxwood, cypress, ebony & linen cord; height: 53 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Throne of Tutankhamun; 1336–1327 BC; wood covered with sheets of gold, silver, semi-precious and other stones, faience, glass and bronze; height: 1 m; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

Ancient Greece

Historical knowledge of Greek furniture is derived from various sources, including literature, terracotta, sculptures, statuettes, and painted vases.[26] Some pieces survive to this day, primarily those constructed from metals, including bronze, or marble.[26] Wood was an important and common material in Greek furniture, both domestic and imported.[26] A common technique was to construct the main sections of the furniture with cheap solid wood, then apply a veneer using an expensive wood, such as maple or ebony.[26] Greek furniture construction also made use of dowels and tenons for joining the wooden parts of a piece together.[26] Wood was shaped by carving, steam treatment, and the lathe, and furniture is known to have been decorated with ivory, tortoise shell, glass, gold or other precious materials.[27]

The modern word "throne" is derived from the ancient Greek thronos (Greek singular: θρόνος), which was a seat designated for deities or individuals of high status/hierarchy or honor.[28] The colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia, constructed by Phidias and lost in antiquity, featured the god Zeus seated on an elaborate throne, which was decorated with gold, precious stones, ebony and ivory, according to Pausanias.[29] Other Greek seats included the klismos, an elegant Greek chair with a curved backrest and legs whose form was copied by the Romans and is now part of the vocabulary of furniture design,[30] the backless stool (diphros), which existed in most Greek homes,[31] and folding stool.[32] The kline, used from the late seventh century BCE,[33] was a multipurpose piece used as a bed, but also as a sofa and for reclining during meals.[34] It was rectangular and supported on four legs, two of which could be longer than the other, providing support for an armrest or headboard.[35] Mattresses, rugs, and blankets may have been used, but there is no evidence for sheets.[34]

In general, Greek tables were low and often appear in depictions alongside klinai.[36] The most common type of Greek table had a rectangular top supported on three legs, although numerous configurations exist, including trapezoid and circular.[37] Tables in ancient Greece were used mostly for dining purposes – in depictions of banquets, it appears as though each participant would have used a single table, rather than a collective use of a larger piece.[38] Tables also figured prominently in religious contexts, as indicated in vase paintings, for example, the wine vessel associated with Dionysus, dating to around 450 BCE and now housed at the Art Institute of Chicago.[39] Chests were used for storage of clothes and personal items and were usually rectangular with hinged lids.[37] Chests depicted in terracotta show elaborate patterns and design, including the Greek fret.[34]

- Foot in the form of a sphinx; circa 600 BC; bronze; overall: 27.6 x 20.3 x 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

- Rod tripod stand; early 6th century BC; bronze; overall: 75.2 x 44.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Pelike which depicts a boy carrying furniture for a symposium (drinking party), in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford, UK)

- Funerary stele in which appears somebody staying on a klismos, from circa 410–400 BC, in the National Archaeological Museum (Athens, Greece)

Ancient Rome

Roman furniture was based heavily on Greek furniture, in style and construction. Rome gradually superseded Greece as the foremost culture of Europe, leading eventually to Greece becoming a province of Rome in 146 BC. Rome thus took over production and distribution of Greek furniture, and the boundary between the two is blurred. The Romans did have some limited innovation outside of Greek influence, and styles distinctly their own.[40]

Roman furniture was constructed principally using wood, metal and stone, with marble and limestone used for outside furniture. Very little wooden furniture survives intact, but there is evidence that a variety of woods were used, including maple, citron, beech, oak, and holly. Some imported wood such as satinwood was used for decoration. The most commonly used metal was bronze, of which numerous examples have survived, for example, headrests for couches and metal stools. Similar to the Greeks, Romans used tenons, dowels, nails, and glue to join wooden pieces together, and also practised veneering.[40]

The 1738 and 1748 excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii revealed Roman furniture, preserved in the ashes of the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius.

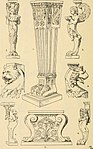

- Illustration of Roman furniture details, from 1900, very similar with Empire style furniture

- Tripod base; circa 100 BC; bronze; overall: 77 x 32.3 x 28 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

- Treasure chest with a sacrifice of Jupiter depicted on it; 1st century AD; wood, iron and bronze, with ageminature; from Pompeii; Naples National Archaeological Museum (Naples, Italy)

- Couch and footstool with bone carvings and glass inlays; 1st–2nd century AD; wood, bone and glass; couch: 105.4 × 76.2 × 214.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Middle Ages

In contrast to the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, and Rome, there is comparatively little evidence of furniture from the 5th to the 15th century.[41] Very few extant pieces survive, and evidence in literature is also scarce.[41] It is likely that the style of furniture prevalent in late antiquity persisted throughout the Middle Ages.[41] For example, a throne similar to that of Zeus is depicted in a sixth-century diptych,[41] while the Bayeux tapestry shows Edward the Confessor and Harold seated on seats similar to the Roman sella curulis.[42] The furniture of the Middle Ages was usually heavy, oak, and ornamented with carved designs.

The Hellenistic influence upon Byzantine furniture can be seen through the use of acanthus leaves, palmettes, bay and olive leaves as ornaments. Oriental influences manifest through rosettes, arabesques and the geometric stylisation of certain vegetal motifs. Christianity brings symbols in Byzantine ornamentation: the pigeon, fishes, the lamb and vines.[43] The furniture from Byzantine houses and palaces was usually luxurious, highly decorated and finely ornamented. Stone, marble, metal, wood and ivory are used. Surfaces and ornaments are gilded, painted plychrome, plated with sheets of gold, emailed in bright colors, and covered in precious stones. The variety of Byzantine furniture is pretty big: tables with square, rectangle or round top, sumptuous decorated, made of wood sometimes inlaid, with bronze, ivory or silver ornaments; chairs with high backs and with wool blankets or animal furs, with coloured pillows, and then banks and stools; wardrobes were used only for storing books; cloths and valuable objects were kept in chests, with iron locks; the form of beds imitated the Roman ones, but have different designs of legs.[44]

The main ornament of Gothic furniture and all applied arts is the ogive. The geometric rosette accompanies the ogive many times, having a big variety of forms. Architectural elements are used at furniture, at the beginning with purely decorative reasons, but later as structure elements. Besides the ogive, the main ornaments are: acanthus leaves, ivy, oak leaves, haulms, clovers, fleurs-de-lis, knights with shields, heads with crowns and characters from the Bible. Chests are the main type of Gothic furniture used by the majority of the population. Usually, the locks and escutcheon of chests have also an ornamental scope, being finely made.[45]

- Throne of Dagobert; 19th and 12th centuries (backrest); gilt bronze; unknown dimensions; Cabinet des Médailles (Paris)[46]

- Gothic coffret (Minnekästchen); circa 1325–1350; oak, inlay, tempera, wrought-iron mounts; overall: 12.1 x 27.3 x 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

- Gothic chest; late 15th century; wood; 30.2 x 29.2 x 39.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gothic chest; late 15th century; walnut and iron; overall: 47 x 38.7 x 75.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Romanian analogion; second quarter of the 16th century; carved, openwork and champlevé wood; 115 x 58 x 65 cm; from the Probota Monastery (Suceava County); National Museum of Art of Romania (Bucharest)[47]

- Russian Monomakhov throne, 1551, wood, unknown dimensions, Dormition Cathedral, Moscow

Renaissance

Along with the other arts, the Italian Renaissance of the fourteenth and fifteenth century marked a rebirth in design, often inspired by the Greco-Roman tradition. A similar explosion of design, and renaissance of culture in general occurred in Northern Europe, starting in the fifteenth century.

- Wardrobe; c.1530; carved walnut; height: 230 cm; Château d'Écouen[49]

- Cassone (chest); c.1550–1560; carved and partially gilded walnut; 86.4 x 181.9 x 67.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

- Cupboard; c.1570; wood; height: 246 cm; Château d'Écouen[50]

- Cupboard; c. 1580; walnut and oak, partially gilded and painted; height: 2.06 m, width: 1.50 m; Louvre[51]

17th and 18th centuries

The 17th century, in both Southern and Northern Europe, was characterized by opulent, often gilded Baroque designs that frequently incorporated a profusion of vegetal and scrolling ornament. Starting in the eighteenth century, furniture designs began to develop more rapidly. Although there were some styles that belonged primarily to one nation, such as Palladianism in Great Britain or Louis Quinze in French furniture, others, such as the Rococo and Neoclassicism were perpetuated throughout Western Europe.

During the 18th century, the fashion was set in England by the French art. In the beginning of the century Boulle cabinets were at the peak of their popularity and Louis XIV was reigning in France. In this era, most of the furniture had metal and enamelled decorations in it and some of the furniture was covered in inlays of marbles lapis lazuli, and porphyry and other stones. By mid-century this Baroque style was displaced by the graceful curves, shining ormolu, and intricate marquetry of the Rococo style, which in turn gave way around 1770 to the more severe lines of Neoclassicism, modeled after the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome.[52] Creating a mass market for furniture, the distinguished London cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director (1754) is regarded as the "first comprehensive trade catalogue of its kind".[53]

There is something so distinct in the development of taste in French furniture, marked out by the three styles to which the three monarchs have given the name of "Louis Quatorze", "Louis Quinze", and "Louis Seize". This will be evident to anyone who will visit, first the Palace of Versailles, then the Grand Trianon, and afterwards the Petit Trianon.[54]

- Baroque pier table; 1685–1690; carved, gessoed, and gilded wood, with a marble top; 83.6 × 128.6 × 71.6 cm; Art Institute of Chicago (US)[56]

- Baroque cupboard; by André Charles Boulle; c.1700; ebony and amaranth veneering, polychrome woods, brass, tin, shell, and horn marquetry on an oak frame, gilt-bronze; 255.5 x 157.5 cm; Louvre[57]

- Baroque commode; by André Charles Boulle; c.1710-1732; walnut veneered with ebony and marquetry of engraved brass and tortoiseshell, gilt-bronze mounts, antique marble top; 87.6 x 128.3 x 62.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)[58]

- Baroque slant-front desk; by Heinrich Ludwig Rohde or Ferdinand Plitzner; c.1715–1725; marquetry with maple, amaranth, mahogany, and walnut on spruce and oak; 90 × 84 × 44.5 cm; Art Institute of Chicago[59]

- Rococo console table; 18th century; carved and gilded wood, marble top; 63.2 × 60 × 25.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rococo commode; by Charles Cressent; c.1745–1749; pine and oak veneered with amaranth and bois satiné, walnut, oak, pine; gilt-bronze, portoro marble top; 87.6 x 139.7 x 57.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rococo slant-top desk; c.1750; oak, kingwood marquetry, amaranth wood, satiné, gilt bronze; unknown dimensions; Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris)[60]

- Rococo side table (commode en console); by Bernard II van Risamburgh; c.1755-1760; Japanese lacquer, gilt-bronze and Sarrancolin marble top; height: 90.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Bureau du Roi (Rococo); by Jean-François Oeben and Jean Henri Riesener; 1760–1769; bronze, marquetry of a variety of fine woods and Sèvres porcelain; 147.3 x 192.5 x 105; Palace of Versailles (Versailles, France)[61]

- Louis XVI style commode of Madame du Barry; by Martin Carlin (attribution); 1772; oak base veneered with pearwood, rosewood and amaranth, soft-paste Sèvres porcelain, bronze gilt, white marble; 87 x 119 cm; Louvre[62]

- Louis XVI style roll-top desk of Marie-Antoinette; by Jean-Henri Riesener; 1784; oak and pine frame, sycamore, amaranth and rosewood veneer, bronze gilt; 103.6 x 113.4 cm; Louvre[63]

- Louis XVI style writing table of Marie-Antoinette; by Adam Weisweiler; 1784; oak, ebony and sycamore veneer, Japanese lacquer, steel, bronze gilt; 73.7 x 81. 2 cm; Louvre[63]

- Louis XVI style folding stool (pliant); 1786; carved and painted beechwood, covered in pink silk; 46.4 × 68.6 × 51.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Louis XVI style armchair (fauteuil) from Louis XVI's Salon des Jeux at Saint Cloud; 1788; carved and gilded walnut, gold brocaded silk (not original); overall: 100 × 74.9 × 65.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

19th century

The nineteenth century is usually defined by concurrent revival styles, including Gothic, Neoclassicism, and Rococo. The design reforms of the late century introduced the Aesthetic movement and the Arts and Crafts movement. Art Nouveau was influenced by both of these movements. Shaker-style furniture became popular during this time in North America as well.

- Empire desk chair; c.1805–1808; mahogany, gilt bronze and satin-velvet upholstery; 87.6 × 59.7 × 64.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

- Empire console table; 1804–1814; mahogany, gilded bronze, chiseled gilded bronze and fossil gray marble; 91.5 x 154 x 73.5 cm; Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris)[64]

- Empire throne; by Bernard Poyet and François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter; 1805; carved and gilded wood, covered in red velvet with silver embroidery; 160 x 110 x 82 cm; Musée des Arts Décoratifs[65]

- Egyptian Revival coin cabinet; 1809–1819; mahogany (probably Swietenia mahagoni), with applied and inlaid silver; 90.2 x 50.2 x 37.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- King of Rome's Cradle (Empire); by Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, Henri Victor Roguier, Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot and Pierre-Philippe Thomire; 1811; wood, silver gilt, mother-of-pearl, sheets of copper covered with velvet, silk and tulle, decorated with silver and gold thread; height: 216 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)[66]

- Chair (one of a pair) from the Gothic Cabinet of the Osmond Countess; by François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter; before 1817–1820; gilt wood; unknown dimensions; Petit Palais (Paris)

- Gothic Revival Chair; 1845–1865; walnut frame with upholstered seat and back; unknown dimensions; Huntington Museum of Art (Huntington, West Virginia, USA)

- tête-à-tête (Second Empire); 1850–1860; rosewood, ash, pine and walnut; 113 x 132.1 x 109.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

- Desk; designed by Frank Furness, made by Daniel Pabst; 1870–1871; walnut, walnut veneer, rosewood (knobs), brass, iron, steel and glass; 196.9 × 157.5 × 81.9 cm; Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia, USA)[67]

- Table (Rococo Revival); c.1880; wood, ormolu and lacquer; 68.9 x 26.99 x 38.42 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles, USA)

- Chair (Art Nouveau); by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo; c.1883; mahogany; 97.79 x 49.53 x 49.53 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Desk (Art Nouveau), presented at the 1900 Paris Exposition; by Émile Gallé; 1900; molded and carved oak, with chiseled and patinated bronze; height: 108.5 cm; Musée d'Orsay (Paris)[68]

Early North American

This design was in many ways rooted in necessity and emphasizes both form and materials. Early British Colonial American[vague] chairs and tables are often constructed with turned spindles and chair backs often constructed with steaming to bend the wood. Wood choices tend to be deciduous hardwoods with a particular emphasis on the wood of edible or fruit bearing trees such as cherry or walnut.[citation needed]

Mid-Century Modern

The first three-quarters of the 20th century is seen as the march towards Modernism. The furniture designers of Art Deco, De Stijl, Bauhaus, Jugendstil, Wiener Werkstätte, and Vienna Secession all worked to some degree within the Modernist motto.

Born from the Bauhaus and Streamline Moderne came the post-World War II style "Mid-Century Modern". Mid-Century Modern materials developed during the war including laminated plywood, plastics, and fiberglass. Prime examples include furniture designed by George Nelson Associates, Charles and Ray Eames, Paul McCobb, Florence Knoll, Harry Bertoia, Eero Saarinen, Harvey Probber, Vladimir Kagan and Danish modern designers including Finn Juhl and Arne Jacobsen.

Contemporary

Industrialisation, Post-Modernism, and the Internet have allowed furniture design to become more accessible to a wider range of people than ever before. There are many modern styles of furniture design, each with roots in Classical, Modernist, and Post-Modern design and art movements. The growth of Maker Culture across the Western sphere of influence has encouraged higher participation and development of new, more accessible furniture design techniques. One unique outgrowth of this post-modern furniture design trajectory is Live Edge, which incorporates the natural surface of a tree as part of a furniture object, heralding a resurgence of these natural shapes and textures within the home.[1] Additionally, the use of Epoxy Resin has become more prevalent in DIY furniture styles.

Ecodesign

Great efforts from individuals, governments, and companies has led to the manufacturing of products with higher sustainability known as Ecodesign. This new line of furniture is based on environmentally friendly design. Its use and popularity are increasing each year.[69]

Postmodernism

Postmodern design, intersecting the Pop art movement, gained steam in the 1960s and 70s, promoted in the 80s by groups such as the Italy-based Memphis movement. Transitional furniture is intended to fill a place between Traditional and Modern tastes.[citation needed]

Asian history

Asian furniture has a quite distinct history. The traditions out of India, China, Korea, Pakistan, Indonesia (Bali and Java) and Japan are some of the best known, but places such as Mongolia, and the countries of South East Asia have unique facets of their own.

Far Eastern

The use of uncarved wood and bamboo and the use of heavy lacquers are well known Chinese styles. It is worth noting that Chinese furniture varies dramatically from one dynasty to the next. Chinese ornamentation is highly inspired by paintings, with floral and plant life motifs including bamboo trees, chrysanthemums, waterlilies, irises, magnolias, flowers and branches of cherry, apple, apricot and plum, or elongated bamboo leaves; animal ornaments include lions, bulls, ducks, peacocks, parrots, pheasants, roosters, ibises and butterflies. The dragon is the symbol of earth fertility, and of the power and wisdom of the emperor. Lacquers are mostly populated with princesses, various Chinese people, soldiers, children, ritually and daily scenes. Architectural features tend toward geometric ornaments, like meanders and labyrinths. The interior of a Chinese house was simple and sober. All Chinese furniture is made of wood, usually ebony, teak, or rosewood for heavier furniture (chairs, tables and benches) and bamboo, pine and larch for lighter furniture (stools and small chairs).[70]

Traditional Japanese furniture is well known for its minimalist style, extensive use of wood, high-quality craftsmanship and reliance on wood grain instead of painting or thick lacquer. Japanese chests are known as Tansu, known for elaborate decorative iron work, and are some of the most sought-after of Japanese antiques. The antiques available generally date back to the Tokugawa and Meiji periods. Both the technique of lacquering and the specific lacquer (resin of Rhus vernicifera) originated in China, but the lacquer tree also grows well in Japan. The recipes of preparation are original to Japan: resin is mixed with wheat flour, clay or pottery powder, turpentine, iron powder or wood coal. In ornamentation, the chrysanthemum, known as kiku, the national flower, is a very popular ornament, including the 16-petal chrysanthemum symbolizing the Emperor. Cherry and apple flowers are used for decorating screens, vases and shōji. Common animal ornaments include dragons, carps, cranes, gooses, tigers, horses and monkeys; representations of architecture such as houses, pavilions, towers, torii gates, bridges and temples are also common. The furniture of a Japanese house consists of tables, shelves, wardrobes, small holders for flowers, bonsais or for bonkei, boxes, lanterns with wooden frames and translucent paper, neck and elbow holders, and jardinieres.[71]

- Chinese low-back armchair; late 16th-18th century (late Ming dynasty to Qing dynasty); huanghuali rosewood; Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Washington D.C.)

- Japanese incense guessing game; 1615–1868; lacquer; overall: 23 x 25.4 x 16.6 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

- Chinese pedestal desk; 1644–1911; huanghuali wood (yellow flowering pear) with brass fittings; Portland Art Museum (Portland, Oregon, USA)

- Japanese chest with cartouche showing figures on donkeys in a landscape; 1750–1800; carved red lacquer on wood core with metal fittings and jade lock; 30.64 x 30.16 x 12.7 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

- Japanese tiered food Box with stand; late 18th century; red lacquer over a wood core, with litharge painting and engraved gold designs; overall: 53 x 68 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

- Chinese moon-gate bed; circa 1876; satinwood (huang lu), other Asian woods and ivory; Peabody Essex Museum (Salem, Massachusetts, USA)

- Chinese canopy bed; late 19th or early 20th century; carved lacquered and gilded wood; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal, Canada)

- Japanese writing table; early 20th century; lacquered wood with silver fittings and various other materials; height: 12.3 cm, length: 60.96 cm, width: 36.83 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Types

For sitting

Seating is amongst the oldest known furniture types, and authors including Encyclopædia Britannica regard it as the most important.[2] In addition to the functional design, seating has had an important decorative element from ancient times to the present day. This includes carved and sculpted pieces intended as works of art, as well as the styling of seats to indicate social importance, with senior figures or leaders granted the use of specially designed seats.[2]

The simplest form of seat is the chair,[72] which is a piece of furniture designed to allow a single person to sit down, which has a back and legs, as well as a platform for sitting.[73] Chairs often feature cushions made from various fabrics.[74]

- Ancient Egyptian armchair of Tutankhamun; 1336–1326 BC; wood, ebony, ivory and gold leaf; height: 71 cm; Exposition of Tutankhamun Treasure in Paris (2019)

- Neoclassical chair; circa 1772; mahogany, covered in modern red Morocco leather; height: 97.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

- Louis XVI armchair (Fauteuil à la reine); 1780–1785; carved and gilded walnut, and embroidered silk satin; height: 102.2 cm, width: 74.9 cm, depth: 77.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Louis XVI settee; designed in circa 1786, woven 1790–91, settee frame from the second half 19th century; carved and gilded wood, with wool and silk; 107.3 × 191.5 × 71.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Types of wood used

All different types of woods have unique signature marks that can help in easy identification of the type. Hardwood and softwood are the two main categories for wood. Both hardwoods and softwoods are used in furniture manufacturing, and each has its own specific uses. Deciduous trees, which have broad leaves that change color periodically throughout the year, are the source of hardwood. Coniferous trees, also known as cone-bearing trees, have small leaves or needles that stay on the tree throughout the year.[75][76] Common softwoods used include pine, redwood and yew. Higher quality furniture tends to be made out of hardwood, including oak, maple, mahogany, teak, walnut, cherry and birch. Highest quality wood will have been air dried to rid it of its moisture.[77]

Cherry

A popular furniture hardwood is American black cherry. Cherry is a light reddish brown to brown color that intensifies into a rich color as it ages, and grows mostly in the eastern United States. Cherry has a tighter grain than birch and is softer. Much cherry lumber is narrow, and it has been utilized to make many lovely classic furniture pieces.[75]

Birch

Birch is a sturdy, durable, even-textured hardwood that is common in the United States and Canada. The wood appears white or creamy yellow to light brown with a crimson tinge in its natural state. Birch is frequently stained to complement other types of wood in furniture. Birch is used to make a lot of transparent, cabinet-grade plywood because it absorbs stain well and finishes beautifully. Birch is frequently used to construct interior doors and cupboards in addition to furniture.[75]

Restoration of furniture

Restoring a piece of furniture may imply attempting to repair and revive the original finish in some way. More often than not, this entails removing the existing treatment and preparing the raw wood for a new finish. Methods for repair depend on what kind of wood it is: solid or veneered, hardwood or softwood, open grained or closed grained. These variables can sometimes decide if a piece of furniture is worth repairing, as well as the type of repairs and finish it will require if it is restored. The 3 methods of restoring furniture are rejuvenate, repair, and refinish.

Rejuvenate The piece can easily be restored by just cleaning and waxing the surface while preserving the current finish. It works on wooden furniture that is still in good shape and is the simplest way to clean it.

Repair This process can fix dents and cracks by touching up some worn-out areas without removing the surface with this technique, the finish can be maintained while repairing the object with specialized products.

Refinish Remove anything that is left for example any paint with a finish-stripper product or lightly sanding the area down and then applying wood finish like oil wax in order to protect the secure the wood.[75]

Cleaning Remove dirt, dust, and grime from the furniture using a mild soap or specialized furniture cleaner.

Standards for design, functionality and safety

- EN 527 Office furniture – Work tables and desks: This European standard specifies requirements and test methods for office work tables and desks, ensuring their functionality and safety.

- EN 1335 Office furniture – Office work chair: This European standard sets requirements for office chairs, focusing on ergonomics and comfort to promote user well-being and productivity.

- ANSI/BIFMA X 5.1 Office Seating: This American National Standard, published by the Business and Institutional Furniture Manufacturers Association (BIFMA), provides requirements for the performance and durability of office seating.

- DIN 4551 Office furniture; revolving office chair: This German standard covers revolving office chairs with adjustable backrests, armrests, and height, ensuring their quality and safety.

- EN 581 Outdoor furniture – Seating and tables for camping, domestic and contract use: This European standard specifies the requirements for outdoor seating and tables used in various settings, including camping and domestic use.

- EN 1728:2014 Furniture – Seating – Test methods for the determination of strength and durability: This European standard outlines test methods to assess the strength and durability of seating furniture, last updated in 2014.

- EN 1730:2012 Furniture – Test methods for the determination of stability, strength, and durability: This European standard provides test methods to evaluate the stability, strength, and durability of various types of furniture.

- BS 4875 Furniture. Strength and stability of furniture: This British Standard focuses on determining the stability of non-domestic storage furniture, helping ensure its safety and reliability.

- EN 747 Furniture – Bunk beds and high beds – Test methods for the determination of stability, strength, and durability: This European standard sets test methods to assess the stability, strength, and durability of bunk beds and high beds.

- EN 13150 Workbenches for laboratories – Safety requirements and test methods: This European standard specifies safety requirements and test methods for laboratory workbenches to ensure safe working conditions.

- EN 1729 Educational furniture, chairs, and tables for educational institutions: This European standard outlines requirements for educational furniture, including chairs and tables, to support comfort and ergonomics in educational settings.

- RAL-GZ 430 Furniture standard from Germany: RAL is a German standardization organization, and RAL-GZ 430 provides guidelines and standards for various types of furniture in Germany.

- NEN 1812 Furniture standard from the Netherlands: NEN is the Dutch Institute for Standardization, and NEN 1812 sets standards for furniture in the Netherlands.

- GB 28007-2011 Children's furniture – General technical requirements for children's furniture: This Chinese standard specifies technical requirements for children's furniture designed and manufactured for children aged 3 to 14.

- BS 5852: 2006 Methods of test for assessment of the ignitability of upholstered seating: This British Standard outlines test methods to assess the ignitability of upholstered seating, both by smoldering and flaming ignition sources.

- BS 7176: This British Standard specifies requirements for the resistance to ignition of upholstered furniture used in non-domestic settings through composite testing. These standards help ensure the quality, safety, and performance of various types of furniture in different regions and applications. Manufacturers and consumers often use these standards as guidelines to meet specific requirements and ensure product reliability.

See also

- Casters which make some furniture moveable

- Furniture designer

- Furniture museum

- Furniture repair

- Metal furniture

- Multifunctional furniture

Notes

- ^ a b Gray, Channing. "Haute and cool: Fine Furnishings show branches out in 10th year with a bigger spread of classic and cutting-edge pieces". The Providence Journal.

- ^ a b c "Furniture". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 February 2016. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "English Translation of "fournir"". Collins French-English Dictionary.

- ^ "English Translation of "fourniture"". Collins French-English Dictionary.

- ^ Weekley 2013, pp. 609–610.

- ^ Solodow 2010, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Smardzewski 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Smardzewski 2015, p. 1.

- ^ a b Smardzewski 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Roebuck 1966, p. 51.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 6.

- ^ a b Roebuck 1966, p. 52.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art 1999, p. 117.

- ^ a b Blakemore 2006, p. 1.

- ^ a b Blakemore 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Gadalla 2007, p. 243.

- ^ Smardzewski 2015, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Smardzewski 2015, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Blakemore 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Litchfield 2011, p. 6.

- ^ a b Litchfield 2011, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Blakemore 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Blakemore 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Blakemore 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Blakemore 2006, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Blakemore 2006, p. 39.

- ^ Richter 1966, p. 125.

- ^ Richter 1966, p. 13.

- ^ Richter 1966, pp. 14, NH 5.11.2ff.

- ^ Linda Maria Gigante, "Funerary Art," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Vol. 1, ed. Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 246.

- ^ Guhl, E.; Koner, W. (1989). Everyday Life in Greek and Roman Times. New York: Crescent. p. 133.

- ^ Wanscher 1980, p. 83.

- ^ Simpson, 253.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Blakemore 2006, p. 43.

- ^ Andrianou, 36.[full citation needed]

- ^ Richter 1966, p. 63.

- ^ a b Blakemore 2006, p. 42.

- ^ Richter 1966, p. 66.

- ^ Chicago Painter. "Stamnos (Mixing Jar)". Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ a b Blakemore 2006, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d Lucie-Smith 1979, p. 33.

- ^ Lucie-Smith 1979, p. 35.

- ^ Bucătaru 1991, p. 172.

- ^ Bucătaru 1991, p. 174.

- ^ Bucătaru 1991, pp. 206, 207, 209, 210 & 211.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Vazaca, Marina (1999). Muzeul Național de Artă al României Ghidul Colecțiilor (in Romanian). Muzeul Național de Artă al României. p. 70. ISBN 2-7118-3840-4.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ unknown (18 September 2013) [before 1923]. A history of feminine fashion. Nabu Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-289-62694-5.

- ^ Houghton Mifflin Company (2003). The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 317. ISBN 978-0618252107.

- ^ Litchfield 2011, p. 211.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ "Pier Table". The Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Bailey 2012, p. 287.

- ^ "Slant-Front Desk". The Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ a b Jacquemart, Albert (2012). Decorative Art. Parkstone. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-84484-899-7.

- ^ Odile, Nouvel-Kammerer (2007). Symbols of Power • Napoleon and the Art of the Empire Style • 1800–1815. Abrams. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8109-9345-7.

- ^ Odile, Nouvel-Kammerer (2007). Symbols of Power • Napoleon and the Art of the Empire Style • 1800–1815. Abrams. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8109-9345-7.

- ^ Odile, Nouvel-Kammerer (2007). Symbols of Power • Napoleon and the Art of the Empire Style • 1800–1815. Abrams. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8109-9345-7.

- ^ "Desk". philamuseum.org. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Paris et l'Art Nouveau". Nº281 Dossier de l'Art (in French). Éditions Faton. 2020.

- ^ "Ecodesign Report – The Results of a survey Amongst Australian Industrial Design Consultancies". Big's Furniture. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Bucătaru 1991, pp. 152, 153, 154 & 156.

- ^ Bucătaru 1991, p. 164, 165 & 166.

- ^ "Physique of office chair". Foss Alborg. 15 August 2016. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ "Definition of CHAIR". www.merriam-webster.com. 3 June 2023.

- ^ Jefferys, Chris (2006). Soft Furnishings. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84330-903-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Types of Wood". Hoove Designs. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Abbas, Abe. "Judge Quality in Wood Furniture". About.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

References

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2012). Baroque & Rococo. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-5742-8.

- Blakemore, Robbie G. (2006). History of interior design & furniture: from ancient Egypt to nineteenth-century Europe. J. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-46433-4.

- Bucătaru, Marina (1991). Stiluri și Ornamente la Mobilier (in Romanian). Editura Didactică și Pedagogică. ISBN 973-30-1079-0.

- Gadalla, Moustafa (2007). The Ancient Egyptian Culture Revealed. Tehuti Research Foundation. ISBN 978-1-931446-27-3.

- Litchfield, Frederick (2011). Illustrated History of Furniture. Arcturus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84837-803-2.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1979). Furniture: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-18173-7.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-907-9.

- Richter, G.M.A. (1966). The Furniture of the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans. Phaidon.

- Roebuck, Carl (1966). The World of Ancient Times. New York: Charles Schribner's Sons Publishing.

- Smardzewski, Jerzy (2015). Furniture Design. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-19533-9.

- Solodow, Joseph B. (2010). Latin Alive: The Survival of Latin in English and the Romance Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48471-8.

- Weekley, Ernest (2013). An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-12287-8.

- Wanscher, Ole (1980). Sella Curulis: The Folding Stool, an Ancient Symbol of Dignity. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger.

External links

- Images of online furniture design available from the Visual Arts Data Service (VADS) – including images from the Design Council Slide Collection.

- History of Furniture Timeline Archived 14 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine From Maltwood Art Museum and Gallery, University of Victoria

- Illustrated History Of Furniture

- Home Economics Archive: Tradition, Research, History (HEARTH)

An e-book collection of over 1,000 books on home economics spanning 1850 to 1950, created by Cornell University's Mann Library. Includes several hundred works on the furniture and interior design in this period, itemized in a specific bibliography. - American Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a fully digitized 2 volume exhibition catalog

![Throne of Dagobert; 19th and 12th centuries (backrest); gilt bronze; unknown dimensions; Cabinet des Médailles (Paris)[46]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Paris_Mus%C3%A9e_Cluny_Tr%C3%B4ne_de_Dagobert_135.jpg/100px-Paris_Mus%C3%A9e_Cluny_Tr%C3%B4ne_de_Dagobert_135.jpg)

![Romanian analogion; second quarter of the 16th century; carved, openwork and champlevé wood; 115 x 58 x 65 cm; from the Probota Monastery (Suceava County); National Museum of Art of Romania (Bucharest)[47]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dd/Analogion_MNaR_11162_%281%29.jpg/84px-Analogion_MNaR_11162_%281%29.jpg)

![Sideboard; c.1524; wood; height: 144 cm; Château d'Écouen (Écouen, France)[48]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/%C3%89couen_%2895%29%2C_ch%C3%A2teau%2C_%C3%A9tage%2C_appt_du_conn%C3%A9table_8.jpg/112px-%C3%89couen_%2895%29%2C_ch%C3%A2teau%2C_%C3%A9tage%2C_appt_du_conn%C3%A9table_8.jpg)

![Wardrobe; c.1530; carved walnut; height: 230 cm; Château d'Écouen[49]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1d/%C3%89couen_%2895%29%2C_ch%C3%A2teau%2C_%C3%A9tage%2C_appt_du_conn%C3%A9table_2.jpg/150px-%C3%89couen_%2895%29%2C_ch%C3%A2teau%2C_%C3%A9tage%2C_appt_du_conn%C3%A9table_2.jpg)

![Cupboard; c.1570; wood; height: 246 cm; Château d'Écouen[50]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/%C3%89couen_Ch%C3%A2teau_d%27%C3%89couen_Innen_Mus%C3%A9e_national_de_la_Renaissance_Schrank_1.jpg/88px-%C3%89couen_Ch%C3%A2teau_d%27%C3%89couen_Innen_Mus%C3%A9e_national_de_la_Renaissance_Schrank_1.jpg)

![Cupboard; c. 1580; walnut and oak, partially gilded and painted; height: 2.06 m, width: 1.50 m; Louvre[51]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Armoire_Louvre_OA_6968.jpg/116px-Armoire_Louvre_OA_6968.jpg)

![Baroque four-poster bed from the Château d'Effiat; c.1650; natural walnut, chiselled Genoa silk velvet and embroidered silks; 295 cm; Louvre[55]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Decorative_arts_in_the_Louvre_-_Room_32_D201903_%28cropped%29.jpg/116px-Decorative_arts_in_the_Louvre_-_Room_32_D201903_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![Baroque pier table; 1685–1690; carved, gessoed, and gilded wood, with a marble top; 83.6 × 128.6 × 71.6 cm; Art Institute of Chicago (US)[56]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Francia%2C_tavolo_da_parete%2C_1685-90_ca.jpg/150px-Francia%2C_tavolo_da_parete%2C_1685-90_ca.jpg)

![Baroque cupboard; by André Charles Boulle; c.1700; ebony and amaranth veneering, polychrome woods, brass, tin, shell, and horn marquetry on an oak frame, gilt-bronze; 255.5 x 157.5 cm; Louvre[57]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/Armoire_aux_perroquets_du_Louvre.jpg/100px-Armoire_aux_perroquets_du_Louvre.jpg)

![Baroque commode; by André Charles Boulle; c.1710-1732; walnut veneered with ebony and marquetry of engraved brass and tortoiseshell, gilt-bronze mounts, antique marble top; 87.6 x 128.3 x 62.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)[58]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/97/Commode_MET_DP108742.jpg/150px-Commode_MET_DP108742.jpg)

![Baroque slant-front desk; by Heinrich Ludwig Rohde or Ferdinand Plitzner; c.1715–1725; marquetry with maple, amaranth, mahogany, and walnut on spruce and oak; 90 × 84 × 44.5 cm; Art Institute of Chicago[59]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/51/Heinrich_ludwig_rohde_o_ferdinand_plitzner_%28attr.%29%2C_scrittoio_a_ribalta%2C_magonza_1720_ca.jpg/139px-Heinrich_ludwig_rohde_o_ferdinand_plitzner_%28attr.%29%2C_scrittoio_a_ribalta%2C_magonza_1720_ca.jpg)

![Rococo slant-top desk; c.1750; oak, kingwood marquetry, amaranth wood, satiné, gilt bronze; unknown dimensions; Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris)[60]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/Secr%C3%A9taire_en_pente_Paris_1745_-_Mus%C3%A9e_des_arts_d%C3%A9coratifs_%28Paris%29_20210629_152741.jpg/147px-Secr%C3%A9taire_en_pente_Paris_1745_-_Mus%C3%A9e_des_arts_d%C3%A9coratifs_%28Paris%29_20210629_152741.jpg)

![Bureau du Roi (Rococo); by Jean-François Oeben and Jean Henri Riesener; 1760–1769; bronze, marquetry of a variety of fine woods and Sèvres porcelain; 147.3 x 192.5 x 105; Palace of Versailles (Versailles, France)[61]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Bureau_du_Roi_vue_de_face_avec_pi%C3%A8ce.jpg/150px-Bureau_du_Roi_vue_de_face_avec_pi%C3%A8ce.jpg)

![Louis XVI style commode of Madame du Barry; by Martin Carlin (attribution); 1772; oak base veneered with pearwood, rosewood and amaranth, soft-paste Sèvres porcelain, bronze gilt, white marble; 87 x 119 cm; Louvre[62]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Commode_de_la_comtesse_du_Barry_%28Louvre%2C_OA_11293%29.jpg/150px-Commode_de_la_comtesse_du_Barry_%28Louvre%2C_OA_11293%29.jpg)

![Louis XVI style roll-top desk of Marie-Antoinette; by Jean-Henri Riesener; 1784; oak and pine frame, sycamore, amaranth and rosewood veneer, bronze gilt; 103.6 x 113.4 cm; Louvre[63]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/Secr%C3%A9taire_%C3%A0_cylindre_de_Marie-Antoinette_%28Louvre%2C_OA_5226%29.jpg/150px-Secr%C3%A9taire_%C3%A0_cylindre_de_Marie-Antoinette_%28Louvre%2C_OA_5226%29.jpg)

![Louis XVI style writing table of Marie-Antoinette; by Adam Weisweiler; 1784; oak, ebony and sycamore veneer, Japanese lacquer, steel, bronze gilt; 73.7 x 81. 2 cm; Louvre[63]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Table_%C3%A0_%C3%A9crire_%C3%A0_pupitre_de_Marie-Antoinette_%28Louvre%2C_OA_5509%29.jpg/112px-Table_%C3%A0_%C3%A9crire_%C3%A0_pupitre_de_Marie-Antoinette_%28Louvre%2C_OA_5509%29.jpg)

![Empire console table; 1804–1814; mahogany, gilded bronze, chiseled gilded bronze and fossil gray marble; 91.5 x 154 x 73.5 cm; Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris)[64]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1e/Console_%28France%2C_premier_Empire_1804-1814%29_-_Mus%C3%A9e_des_arts_d%C3%A9coratifs_%28Paris%29_20210629_154120.jpg/150px-Console_%28France%2C_premier_Empire_1804-1814%29_-_Mus%C3%A9e_des_arts_d%C3%A9coratifs_%28Paris%29_20210629_154120.jpg)

![Empire throne; by Bernard Poyet and François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter; 1805; carved and gilded wood, covered in red velvet with silver embroidery; 160 x 110 x 82 cm; Musée des Arts Décoratifs[65]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Tr%C3%B4ne_de_Napol%C3%A9on_1er_en_provenance_du_Corps_l%C3%A9gislatif_-_Exposition_Versailles.jpg/99px-Tr%C3%B4ne_de_Napol%C3%A9on_1er_en_provenance_du_Corps_l%C3%A9gislatif_-_Exposition_Versailles.jpg)

![King of Rome's Cradle (Empire); by Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, Henri Victor Roguier, Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot and Pierre-Philippe Thomire; 1811; wood, silver gilt, mother-of-pearl, sheets of copper covered with velvet, silk and tulle, decorated with silver and gold thread; height: 216 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)[66]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Austria-03324_-_Cradle_of_Napoleon%27s_Son_%2832936041295%29.jpg/100px-Austria-03324_-_Cradle_of_Napoleon%27s_Son_%2832936041295%29.jpg)

![Desk; designed by Frank Furness, made by Daniel Pabst; 1870–1871; walnut, walnut veneer, rosewood (knobs), brass, iron, steel and glass; 196.9 × 157.5 × 81.9 cm; Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia, USA)[67]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/Desk%2C_designed_by_Frank_Furness%2C_1870-71%2C_Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art.jpg/123px-Desk%2C_designed_by_Frank_Furness%2C_1870-71%2C_Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

![Desk (Art Nouveau), presented at the 1900 Paris Exposition; by Émile Gallé; 1900; molded and carved oak, with chiseled and patinated bronze; height: 108.5 cm; Musée d'Orsay (Paris)[68]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/%C3%89mile_gall%C3%A9%2C_bureau_%27foresta_lorenese%27%2C_1900.JPG/118px-%C3%89mile_gall%C3%A9%2C_bureau_%27foresta_lorenese%27%2C_1900.JPG)