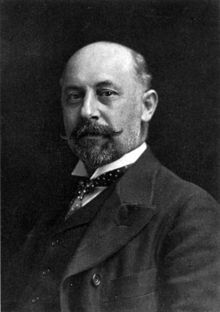

Frederick Ruckstull

Frederick Ruckstull | |

|---|---|

c. 1902 | |

| Born | Frederick Wellington Ruckstull May 22, 1853 Breitenbach-Haut-Rhin, France |

| Died | May 26, 1942 (aged 89) New York, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Frederick Wellington Ruckstull (German: Friedrich Ruckstuhl; May 22, 1853 – May 26, 1942) was a French-born American sculptor and art critic.

Life and career

Born Ruckstuhl in Breitenbach, Alsace, France, his family moved to St. Louis, Missouri,[1] in 1855. He worked at a variety of unsatisfying jobs until his early twenties when an art exhibition in St. Louis inspired him to become a sculptor. He studied art locally, visited Paris and then worked for years as a toy store clerk to save enough to study in Paris for three years. In 1885, Ruckstull entered the Académie Julian, and studied under Gustave Boulanger, Camille Lefèvre, Jean Dampt and Antonin Mercié. He considered studying with Auguste Rodin, but claimed to be disgusted with his style.

On returning to U.S. in 1892, Ruckstull opened a studio in New York City. His work Evening won the grand medal for sculpture at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. As a result of this national exposure, he was commissioned to make an equestrian statue of Major-General John F. Hartranft for the Pennsylvania State University. In 1893, Ruckstull was appointed to teach modeling and marble carving at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Schools in New York City.[2]

He was also deeply involved with creating Confederate memorial sculpture, forging a sculptural iconography for the Southern ideology of the Lost Cause.[3]

Ruckstull was a founding member of the National Sculpture Society as well as the editor of the conservative magazine Art World, where he wrote under the pseudonym Petronius Arbiter, a reference to the Satyricon. In the spring of 1917, he wrote a manifesto inveighing against degenerate modernist art, where he attacked both the artworks and the artists, using racist tropes and the quasi-medical language of physiognomy to attack them.[3]

In 1925 he wrote the book Great Works of Art and What Makes Them Great, a collection of essays he had published previously, which has recently been reprinted. His sculpture was in the figurative Beaux-Arts style, with its realism, and detailed modeling. He and other prominent sculptors of the era such as Daniel Chester French championed the French style of studio system teaching, art societies, and exhibitions. Following the Armory Show of 1913, he continued to represent the old guard of academic sculpture, a perspective clearly expressed in his book.

Ruckstull married in 1896 and had one son. He died at his home in New York on May 26, 1942, four days after his 89th birthday, and was cremated.[4]

Works

- Evening, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument, also known as Victory or the Peace Monument, in Major John Mark Park, Jamaica, Queens, New York City (1896)

- Statue of Wade Hampton III, National Statuary Hall Collection, United States Capitol (1929)

- Wade Hampton, equestrian statue South Carolina State House grounds (1906)

- Solon, Reading Room, Library of Congress

- Wisdom and Force, Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State

- Altar to Liberty: Minerva, Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY (1920)

- Dongan Oak Monument, Battle Pass, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, NY (1922)

- Busts, front portico, Library of Congress

- Uriah Milton Rose, National Statuary Hall Collection United States Capitol

- John F. Hartranft, Pa. Capitol, Harrisburg

- Confederate Monument, Baltimore, Maryland

- Phoenicia New York Custom House

- Defense of the Flag, Little Rock, Arkansas

- Angels of the Confederacy, Columbia, South Carolina.

- John C. Calhoun, National Statuary Hall Collection United States Capitol

- Soldiers' Monument, Stafford Springs, Connecticut

- Charles Duncan McIver[permanent dead link], University of North Carolina at Greensboro, dedicated to the school on October 5, 1912, an anniversary of the school's founding

- Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Baltimore, Maryland, dedicated on May 2, 1903[5]

References

Notes

- ^ Ruckstull, F. W. (1925). Great Works of Art and what Makes Them Great: 175 Illustrations, p. 517. Garden City Publ. ISBN 0-7661-7108-6. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Finding aid for Schools of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Records (1879–1895). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ a b Lobel, Michael (June 27, 2020). "American Degeneracy".

- ^ "Frederick Wellington Ruckstull, Sculptor of Monuments Here". Brooklyn Eagle. May 27, 1942. p. 11. Retrieved May 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ kelly, Cindy (May 3, 2011). Outdoor Sculpture in Baltimore: A Historical Guide to Public Art in the Monumental City. JHU Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780801897221.

External links

- National Sculpture Society

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Frederick Ruckstull in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website