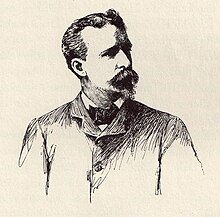

Frank T. Merrill

Frank Thayer Merrill | |

|---|---|

Frank T. Merrill, self-portrait | |

| Born | December 14, 1848 Roxbury, Massachusetts, US |

| Died | October 12, 1936 (aged 87) Dorchester, Massachusetts, US |

| Known for | Book illustration |

| Notable work |

|

| Years active | 1870s–1920s |

| Signature | |

| |

Frank Thayer Merrill (December 14, 1848 – October 12, 1936)[1] was an American artist and illustrator. He is best known for his drawings for the first illustrated edition of Louisa May Alcott's novel Little Women, published in 1880. Over a five-decade career, he illustrated a wide variety of works for adults and children.

Early life and education

Frank Thayer Merrill was born on December 14, 1848, to George William Merrill (1824–1879) and Sarah Rose Merrill (née Alden, 1822–1895) in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Both parents were natives of Westbrook, Maine. His father was descended from Nathaniel Merrill, who emigrated from England to Massachusetts in 1635.[2] His mother was a direct descendant of John Alden, of the Mayflower crew.[a]

He attended local public schools, graduating from either Roxbury High School[3] or Boston Latin School[4] — sources disagree. (The 1865 state census lists the 16-year-old Merrill's occupation as "clerk" rather than "student".[5]) His mother "greatly encouraged Merrill's artistic development and from her much of his talent is said to have come".[4] Merrill participated in the free drawing program at the Lowell Institute from 1864 to 1875, and entered the school of drawing and painting at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1875.[6]

Career

In 1870, Merrill established a studio in Roxbury[b] where he dedicated himself to a career as an illustrator as well as painting in watercolor and oil. He traveled to Europe in 1884, painting and sketching in France, Switzerland, Belgium, The Netherlands and England.[6]

He drew on his observations of Parisian life along the Seine river to write a story titled Through the Heart of Paris. It appeared in the January 1886 issue of the children's magazine Wide Awake[7] and was included in a collection of Wide Awake travel articles, Sights Worth Seeing by Those Who Saw Them, also published in 1886.

"On the right bank of the river, near the Pont de la Concorde and opposite the bathhouse where we have taken our refreshing dip, is another bathing place. But here the bathers pay no fees, wear no bathing dresses, have no absinthe or cigarettes. [...] It is a lively scene, very picturesque. Some of the horses are ridden into the water by men whose red caps show them to be soldiers, others have been taken from between the shafts of wagons and carts in the street above, and their drivers in blouses, or shirts, or naked to the waist, ride them splashing and floundering about, men and horses equally wet."

Collaboration with Louisa May Alcott

Merrill's first major commission was to illustrate a new edition of Little Women.[8] Originally released in two volumes in 1868 and 1869, a single-volume revised edition was published in 1880 to capitalize on the book's popularity and to deter copyright violators.[9] Merrill created over two hundred pen-and-ink drawings for the new edition.

In 2002, the Concord Museum in Concord, Massachusetts, mounted an exhibition of sixty-five of Merrill's original drawings for Little Women, some with annotations by the author giving both praise and editorial direction.[10]

Alcott was pleased with the final drawings, writing to her publisher:

The drawings are all capital, and we had great fun over them down here this rainy day.... Mr. Merrill certainly deserves a good penny for his work. Such a fertile fancy and quick hand as his should be well paid, and I shall not begrudge him his well-earned compensation, nor the praise I am sure these illustrations will earn.

— Letter to Thomas Niles of Roberts Brothers, July 20, 1880[11]

Merrill also illustrated some of Alcott's books re-issued after her death, including: An Old-Fashioned Girl (1898 Roberts Brothers edition) and Little Men (1904 Little, Brown & Co. edition).

Mark Twain and The Prince and the Pauper

Shortly after Little Women was published, Merrill was asked to supply illustrations for the first edition of The Prince and the Pauper (1881) by Mark Twain. He shared credit with John J. Harley and Ludvig Sandöe Ipsen for the 192 illustrations.

Twain commented favorably on Merrill's drawings in letters to his publisher:

As to the pictures, they clear surpass my highest expectations. They are as dainty and rich as etching.

— Letter to Benjamin Ticknor, August 1, 1881[12]

Other work

Over the course of his career, Merrill created thousands of illustrations for a wide variety of fiction and non-fiction for children and adults. Some of his earliest work appears in a history titled Pioneers in the Settlement of America published in 1877.[13] He went on to illustrate a number of other histories, primarily for children, sharing his deep interest in American history, particularly the colonial and revolutionary eras.[14] These include:

- Legends of ye Province House (1890) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- The American History Story Book (1911) and Heroic Deeds of American Sailors (1917) by Albert F. Blaisdell and Francis K. Ball

- In the Days of Thomas Jefferson (1900) by Hezekiah Butterworth

- The Knitting of the Souls: A Tale of 17th Century Boston (1904) by Maude Clark Gay

- Prisoners of the Pirates: A Tale of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (1913) by Ruel Perley Smith

Many of the works Merrill contributed to were reissues of American and English classics:

- Rip van Winkle (1888) and Tales of a Traveller (1897) by Washington Irving

- The Courtship of Miles Standish (1883) by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

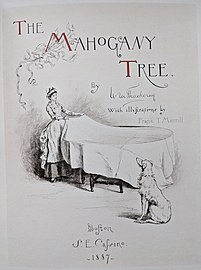

- Vanity Fair (1893) and The Mahogany Tree (1887) by William Makepeace Thackeray

- The Man without a Country (1900) by Edward Everett Hale

- Lorna Doone (1892) by R. D. Blackmore

- Adam Bede (1893) by George Eliot

- The Count of Monte Cristo (1915) and a number of other romances by Alexandre Dumas.

He also supplied illustrations for contemporary, or popular, fiction:

- The Mysteries of Paris (1903) by Eugene Sue

- Love Me Little, Love Me Long (1910) by Charles Reade

- Hope Loring (1902) by Lillian Bell

- Omar, the Tentmaker (1922) by Nathan Haskell Dole

- The Yellow God, an Idol of Africa (1908) by H. Rider Haggard

Merrill specialized in children's books, or what might be called Young Adult fiction. Many were entries in multi-book series for which he provided illustrations for one or more volumes.[15]

- Lynx-hunting (The Camping-Out series, vol IV) (1872) by Charles Asbury Stephens

- Captain January (1892) and Star Bright (1927) by Laura E. Richards

- A Boy's Adventure, or, The Strange Adventures of Ben Baker (1898) by Horatio Alger Jr.

- An Annapolis Plebe (1907) by Edward L. Beach Sr., the first in a series about naval life.

- The Six Little Pennypackers (1911) by Sophie Swett

- Mary Ware in Texas (1919) by Annie Fellowes Johnston

- The Young Wireless Operator with the Oyster Fleet (1922) by Lewis E. Theiss. Merrill illustrated nine of ten entries in the Wireless Patrol series.

- Lonely O'Malley (1924) by Arthur Stringer

- Merrylips (1925) by Beulah Marie Dix

Merrill displayed considerable skill as a calligrapher. His editions of two Christmas poems, Thackeray's The Mahogany Tree[16] and A Christmas Carroll, written in 1622 by George Wither,[17] are entirely rendered with full-page drawings, decorative elements and hand-lettered text.

- The Mahogany Tree (1887), title page

- The Mahogany Tree (1887), "Christmas is here"

- A Christmas Carroll (1907), title page

- A Christmas Carroll (1907), frontispiece

- A Christmas Carroll (1907), dedication by Merrill to his wife

- A Christmas Carroll (1907), page 27, "Weele bury't in a Christmas Pye

And evermore be merry."

Exhibitions

Merrill exhibited in a number of art galleries, including the Salmagundi Club in New York City.[18] A Boston newspaper reviewed an 1885 exhibition of watercolors at Chase's Art Gallery. (The Bromley Arms, which became the Donnithorne Arms in George Eliot's novel Adam Bede, was painted by Merrill when he was in England.)

The first twelve have a double interest, being sketches from the scene of "Adam Bede", and to the readers of this immortal book they will prove very interesting. "The Bromley Arms" is very delicate in handling, and the color is quiet and cool; the grays are soft but rather ordinary; there is a lack of fine feeling for minute gradation. The perspective is more than good; the tottering stone wall in the left foreground is particularly well managed; the geese are cleverly drawn and with considerable character.

— Art Notes, Boston Evening Transcript, April 30, 1885[19]

Another newspaper review of a 1905 exhibition at Walter Rowland's galleries was also complimentary.

The artist had a desirable opportunity opened to him when he was commissioned to illustrate new editions of the poems of Keats and Shelley, and, with the opportunity, a severe test was imposed. [...] We all know how much more beautiful are the pictures which have never been painted than any pictures that actually exist. [...] it must be said the Mr. Merrill has acquitted himself of his task very creditably indeed. Among the thirty illustrations [...] are many which are most interesting and sympathetic. Not less so are the drawings made to illustrate Dumas's romances.

— Mr. Merrill's Exhibition, Boston Evening Transcript, March 1, 1905[20]

Crime in the book business

In 1914, Merrill appeared as a witness in a case of "larceny and conspiracy" regarding the sale of a collection of books.[21] When asked his opinion of the illustrations in one of the books, he replied, "It's not a very gracious thing for one artist to criticize another but as I see this I will say it doesn't appeal to me". Merrill also stated that he was paid "a little in excess of $1,900" for illustrations made for editions of the collected works of Keats and Shelley, which were among the books involved in the lawsuit. He added that he was paid $60 for each of four drawings for books by Mark Twain, probably referring to a commission for four full-page illustrations for a new edition of The Prince and the Pauper which was published in 1899.[22]

Personal life

Merrill married Jessie S. Aldrich (1858–1936) of Boston on December 14, 1881, at the Walnut Avenue (now Eliot) Congregational Church in Roxbury.[23] The couple lived in Roxbury until 1886 when they moved to a newly built house and studio on Tremlett St. in the Codman Square neighborhood of Dorchester. Merrill worked out of this studio for the rest of his life.[24]

The Merrills had four sons:

- Alden (1882–1957) SB in chemistry, MIT, 1906. Married Emeline L. Cook in Torrington, Connecticut, 1910.[25]

- Paul A. (1888–1891) Died of pneumonia and influenza.[26]

- Philip Aldrich (1893–1972)[27][28] Married Marion C. Hill (1897–1972)[29]

- Roger (1894–1952)[30]

A life-long resident of Boston, Merrill was active in the community. He gave talks to local groups on illustration and historic costuming, drawing on his experience collecting and restoring American antiques.[14][32] In 1886, a charity event, "Music of the Centuries", was staged for the New England Conservatory. Merrill was credited for work on two tableaux: as artist for "Court of Charlemagne (A.D. 800)" and as artist and manager for "Cavaliers and Roundheads (A.D. 1645)".[33] A Republican, he served as an inspector of elections for his city precinct. He was elected vice-president of the Corporation of Mount Pleasant Home for Aged Men and Women in 1908. Mrs. Merrill was also on the executive committee.

On December 14, 1931, Jessie and Frank Merrill celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary (which was also Frank's birthday) at the home where they had resided for 45 years, in the company of friends, and their three sons.[34] Jessie died a few years later,[35] followed by Frank within three months.[36] Both were interred in the family plot at Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

Gallery

- "North Bridge, Concord, Massachusetts, April 19, 1775", 1909

- Sir Gawain seized his lance and bade them farewell. A Knight of King Arthur's Court by John H. Cox, 1910

- "I'll try—I'll try to make you happy". The King's Mirror by Anthony Hope, 1899

- Frontispiece, Half a Dozen Boys by Anna Chapin Ray, 1895

- Chapter head, Half a Dozen Boys by Anna Chapin Ray, 1895

- "Why ain't you a-gittin' some schoolin'?", Lonely O'Malley by Arthur Stringer, 1905

- A Legend of the Old Elm, Isaac McLellan, Jr., "The Money-Digger", 1884

- "This, I suppose, is the work of M. Cabrion.", The Mysteries of Paris by Eugène Sue, c. 1900

- Rip Van Winkle by Washington Irving (1888) Title page

- "A company of odd-looking personages", Rip Van Winkle, 1888

- "He used to tell his story to every stranger", Rip Van Winkle, 1888

- "In old tattered slippers", The Cane-bottom'd Chair by Thackeray, 1891

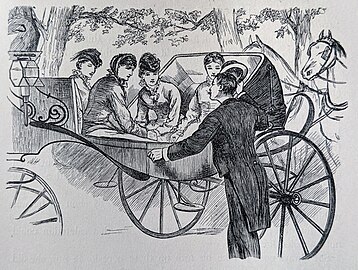

- Little Women (1880) "He put the sisters into the carriage."

Notes and References

Notes

References

- ^ "Obituaries". The Boston Globe. October 14, 1936. p. 34. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Merrill 1983, p. 430

- ^ Robinson 1888, p. 133

- ^ a b Merrill 1966, p. 15

- ^ "Massachusetts State Census, 1865", database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MQCT-J3P : 22 February 2021), Frank Merrill in entry for George W Merrill, 1865.

- ^ a b

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Frank Thayer Merrill". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Boston: American Biographical Society.

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Frank Thayer Merrill". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Boston: American Biographical Society.

- ^ Merrill, Frank T. (January 1866). "Through the Heart of Paris". Wide Awake. Vol. 22, no. 2. Boston, Massachusetts: D. Lothrop and Company. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/27106 Little Women at Project Gutenberg

- ^ Gowen 2010, p. 12

- ^ https://concordmuseum.org/events/illustrating-little-women-louisa-may-alcott-and-frank-thayer-merrill/ Illustrating Little Women at the Concord Museum

- ^ Alcott 1898, p. 334

- ^ Twain 1967, p. 138

- ^ Crafts, William A. (1877). Pioneers in the Settlement of America. Boston: Samuel Walker and Company. OCLC 1050799404.

- ^ a b Merrill 1966, p. 16

- ^ Gowen 2010, pp. 13–15 List of serials illustrated by Merrill

- ^ The Mahogany Tree at the HathiTrust Digital Library

- ^ A Christmas Carroll at the HathiTrust Digital Library

- ^ Robinson 1888, p. 136

- ^ "Art Notes". Boston Evening Transcript. April 30, 1885. p. 6. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ "Mr. Merrill's Exhibition". Boston Evening Transcript. March 1, 1905. p. 14. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ "Paid $1900 for Illustrating, Merrill a Witness at 'De Luxe' Book Trial". The Boston Globe. March 25, 1914. p. 3. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ http://www.twainquotes.com/UniformEds/UniformEdsCh18.html History of the 1881 edition of The Prince and the Pauper

- ^ "Massachusetts, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1626-2001," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FH8P-CXG : 10 November 2020), Frank Merrill, 14 Dec 1881; citing Marriage, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, United States, Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth, Boston; FHL microfilm 004276983.

- ^ Robinson 1888, p. 138

- ^ Who's Who in Engineering, p. 867, at Google Books

- ^ "Massachusetts Deaths, 1841-1915, 1921-1924," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NWSN-QYD : 2 March 2021), Paul A. Merrill, 26 Dec 1891; citing Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, v 420 p 446, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 961,505.

- ^ "Massachusetts, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1626-2001," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F42D-XQP : 21 October 2020), Philip A./Merrill, 28 Jul 1893; citing Birth, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth, Boston; FHL microfilm 004276278.

- ^ "Massachusetts Death Index, 1970-2003", database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VZTH-QKC : 13 June 2019), Philip A Merrill, 1972.

- ^ "Massachusetts Marriages, 1841-1915," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q28K-7D61 : 10 March 2021), Frank T Merrill in entry for Philip A Merrill and Marion C Hill, 6 Oct 1922; citing Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, United States, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 830,689.

- ^ "United States, Enlisted and Officer Muster Rolls and Rosters, 1916-1939", database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6DMM-TBML : 28 January 2022), Roger Merrill, 1916.

- ^ Merrill 1983, pp. 107–116 "A Few Questions of Heraldry"

- ^ "Dorchester Women's Club". Boston Evening Transcript. March 7, 1914. p. 24.

- ^ "Music of the Centuries". The Boston Globe. April 26, 1886. p. 7. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ "Mr and Mrs F. T. Merrill Mark Golden Wedding". The Boston Globe. December 15, 1931. p. 2. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ "Obituaries". The Boston Globe. July 15, 1936. p. 26. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ "Obituaries". The Boston Globe. October 14, 1936. p. 36. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

Sources

- Alcott, Louisa May (1898). Cheney, Ednah D. (ed.). Louisa May Alcott: Her Life, Letters and Journals. Boston: Little, Brown & Company. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- Gowen, William R. (November–December 2010). "Master of his craft: Frank Thayer Merrill as children's book illustrator" (PDF). Newsboy. Richmond: Horatio Alger Society (published 2010). Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Merrill, John Alden Jr. (Summer 1966). "Frank Thayer Merrill's Boston Sketches". Old-Time New England. Vol. 56, no. 1. Boston, Massachusetts: The Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

- Merrill, Samuel (1983) [Originally published 1917–1928]. A Merrill Memorial. Newburyport, Massachusetts: Parker River Researchers. OCLC 1036672066. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Robinson, Frank Torrey (1888). Living New England Artists. Boston, Massachusetts: S. E. Cassino. LCCN 13016209. OCLC 1048799502. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- Twain, Mark (1967). Hill, Hamlin Lewis (ed.). Mark Twain's Letters to his Publishers, 1867-1894. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-00560-0. OCLC 272071. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

External links

- Works by Frank T. Merrill at Open Library

- Works by Frank T. Merrill at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Frank T. Merrill at the Internet Archive

- Works illustrated by Frank T. Merrill at HathiTrust

- Frank Thayer Merrill at the Dorchester Atheneum

- List of Merrill illustrations for Little Women held by the Concord Free Public Library