Firestorm

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

A firestorm is a conflagration which attains such intensity that it creates and sustains its own wind system. It is most commonly a natural phenomenon, created during some of the largest bushfires and wildfires. Although the term has been used to describe certain large fires,[1] the phenomenon's determining characteristic is a fire with its own storm-force winds from every point of the compass towards the storm's center, where the air is heated and then ascends.[2][3]

The Black Saturday bushfires, the 2021 British Columbia wildfires, and the Great Peshtigo Fire are possible examples of forest fires with some portion of combustion due to a firestorm, as is the Great Hinckley Fire. Firestorms have also occurred in cities, usually due to targeted explosives, such as in the aerial firebombings of London, Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Mechanism

A firestorm is created as a result of the stack effect as the heat of the original fire draws in more and more of the surrounding air. This draft can be quickly increased if a low-level jet stream exists over or near the fire. As the updraft mushrooms, strong inwardly-directed gusty winds develop around the fire, supplying it with additional air. This would seem to prevent the firestorm from spreading on the wind, but the tremendous turbulence created may also cause the strong surface inflow winds to change direction erratically. Firestorms resulting from the bombardment of urban areas in the Second World War were generally confined to the areas initially seeded with incendiary devices, and the firestorm did not appreciably spread outward.[4]

A firestorm may also develop into a mesocyclone and induce true tornadoes/fire whirls. This occurred with the 2002 Durango fire,[5] and probably with the much greater Peshtigo Fire.[6][7] The greater draft of a firestorm draws in greater quantities of oxygen, which significantly increases combustion, thereby also substantially increasing the production of heat. The intense heat of a firestorm manifests largely as radiated heat (infrared radiation), which may ignite flammable material at a distance ahead of the fire itself.[8][9][failed verification] This also serves to expand the area and the intensity of the firestorm.[failed verification] Violent, erratic wind drafts suck movables into the fire and as is observed with all intense conflagrations, radiated heat from the fire can melt some metals, glass, and turn street tarmac into flammable hot liquid. The very high temperatures ignite anything that might possibly burn, until the firestorm runs low on fuel.

A firestorm does not appreciably ignite material at a distance ahead of itself; more accurately, the heat desiccates those materials and makes them more vulnerable to ignition by embers or firebrands, increasing the rate of fire spotting. During the formation of a firestorm many fires merge to form a single convective column of hot gases rising from the burning area and strong, fire-induced, radial (inwardly directed) winds are associated with the convective column. Thus the fire front is essentially stationary and the outward spread of fire is prevented by the in-rushing wind.[10]

Characterization of a firestorm

A firestorm is characterized by strong to gale-force winds blowing toward the fire, everywhere around the fire perimeter, an effect which is caused by the buoyancy of the rising column of hot gases over the intense mass fire, drawing in cool air from the periphery. These winds from the perimeter blow the fire brands into the burning area and tend to cool the unignited fuel outside the fire area so that ignition of material outside the periphery by radiated heat and fire embers is more difficult, thus limiting fire spread.[4] At Hiroshima, this inrushing to feed the fire is said to have prevented the firestorm perimeter from expanding, and thus the firestorm was confined to the area of the city damaged by the blast.[11]

Large wildfire conflagrations are distinct from firestorms if they have moving fire fronts which are driven by the ambient wind and do not develop their own wind system like true firestorms. (This does not mean that a firestorm must be stationary; as with any other convective storm, the circulation may follow surrounding pressure gradients and winds, if those lead it onto fresh fuel sources.) Furthermore, non-firestorm conflagrations can develop from a single ignition, whereas firestorms have only been observed where large numbers of fires are burning simultaneously over a relatively large area,[13] with the important caveat that the density of simultaneously burning fires needs to be above a critical threshold for a firestorm to form (a notable example of large numbers of fires burning simultaneously over a large area without a firestorm developing was the Kuwaiti oil fires of 1991, where the distance between individual fires was too large).

The high temperatures within the firestorm zone ignite most everything that might possibly burn, until a tipping point is reached, that is, upon running low on fuel, which occurs after the firestorm has consumed so much of the available fuel within the firestorm zone that the necessary fuel density required to keep the firestorm's wind system active drops below the threshold level, at which time the firestorm breaks up into isolated conflagrations.

In Australia, the prevalence of eucalyptus trees that have oil in their leaves results in forest fires that are noted for their extremely tall and intense flame front. Hence the bush fires appear more as a firestorm than a simple forest fire. Sometimes, emission of combustible gases from swamps (e.g., methane) has a similar effect. For instance, methane explosions enforced the Peshtigo Fire.[6][14]

Weather and climate effects

Firestorms will produce hot buoyant smoke clouds of primarily water vapor that will form condensation clouds as it enters the cooler upper atmosphere, generating what is known as pyrocumulus clouds ("fire clouds") or, if large enough, pyrocumulonimbus ("fire storm") clouds. For example, the black rain that began to fall approximately 20 minutes after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima produced in total 5–10 cm of black soot-filled rain in a 1–3 hour period.[15] Moreover, if the conditions are right, a large pyrocumulus can grow into a pyrocumulonimbus and produce lightning, which could potentially set off further fires. Apart from city and forest fires, pyrocumulus clouds can also be produced by volcanic eruptions due to the comparable amounts of hot buoyant material formed.

On a more continental and global extent, away from the direct vicinity of the fire, wildfire firestorms that produce pyrocumulonimbus cloud events have been found to "surprisingly frequently" generate minor "nuclear winter" effects.[16][12][17][18] These are analogous to minor volcanic winters, with each mass addition of volcanic gases additive in increasing the depth of the "winter" cooling, from near-imperceptible to "year without a summer" levels.

Pyro-cumulonimbus and atmospheric effects (in wildfires)

A very important but poorly understood aspect of wildfire behavior are pyrocumulonimbus (pyroCb) firestorm dynamics and their atmospheric impact. These are well illustrated in the Black Saturday case study below. The "pyroCb" is a fire-started or fire-augmented thunderstorm that in its most extreme manifestation injects huge abundances of smoke and other biomass-burning emissions into the lower stratosphere. The observed hemispheric spread of smoke and other biomass-burning emissions has known important climate consequences. Direct attribution of the stratospheric aerosols to pyroCbs only occurred in the last decade.[19]

Such an extreme injection by thunderstorms was previously judged to be unlikely because the extratropical tropopause is considered to be a strong barrier to convection. Two recurring themes have developed as pyroCb research unfolds. First, puzzling stratospheric aerosol-layer observations—and other layers reported as volcanic aerosol can now be explained in terms of pyroconvection. Second, pyroCb events occur surprisingly frequently, and they are likely a relevant aspect of several historic wildfires.[19]

On an intraseasonal level it is established that pyroCbs occur with surprising frequency. In 2002, at least 17 pyroCbs erupted in North America alone. Still to be determined is how often this process occurred in the boreal forests of Asia in 2002. However, it is now established that this most extreme form of pyroconvection, along with more frequent pyrocumulus convection, was widespread and persisted for at least two months. The characteristic injection height of pyroCb emissions is the upper troposphere, and a subset of these storms pollutes the lower stratosphere. Thus, a new appreciation for the role of extreme wildfire behavior and its atmospheric ramifications is now coming into focus.[19]

Black Saturday firestorm (Wildfire case study)

Background

The Black Saturday bushfires are some of Australia's most destructive and deadly fires that fall under the category of a "firestorm" due to the extreme fire behavior and relationship with atmospheric responses that occurred during the fires. This major wildfire event led to a number of distinct electrified pyrocumulonimbus plume clusters ranging roughly 15 km high. These plumes were proven susceptible to striking new spot fires ahead of the main fire front. The newly ignited fires by this pyrogenic lightning further highlight the feedback loops of influence between the atmosphere and fire behavior on Black Saturday associated with these pyroconvective processes.[20]

Role that pyroCbs have on fire in case study

The examinations presented here for Black Saturday demonstrate that fires ignited by lightning generated within the fire plume can occur at much larger distances ahead of the main fire front—of up to 100 km. In comparison to fires ignited by burning debris transported by the fire plume, these only go ahead of the fire front up to about 33 km, noting that this also has implications in relation to understanding the maximum rate of spread of a wildfire. This finding is important for the understanding and modeling of future firestorms and the large scale areas that can be affected by this phenomenon.[20]

As the individual spot fires grow together, they will begin to interact. This interaction will increase the burning rates, heat release rates, and flame height until the distance between them reaches a critical level. At the critical separation distance, the flames will begin to merge and burn with the maximum rate and flame height. As these spot fires continue to grow together, the burning and heat release rates will finally start to decrease but remain at a much elevated level compared to the independent spot fire. The flame height is not expected to change significantly. The more spot fires, the bigger the increase in burning rate and flame height.[21]

Importance for continued study of these firestorms

Black Saturday is just one of many varieties of firestorms with these pyroconvective processes and they are still being widely studied and compared. In addition to indicating this strong coupling on Black Saturday between the atmosphere and the fire activity, the lightning observations also suggest considerable differences in pyroCb characteristics between Black Saturday and the Canberra fire event. Differences between pyroCb events, such as for the Black Saturday and Canberra cases, indicate considerable potential for improved understanding of pyroconvection based on combining different data sets as presented in the research of the Black Saturday pyroCb's (including in relation to lightning, radar, precipitation, and satellite observations).[20]

A greater understanding of pyroCb activity is important, given that fire-atmosphere feedback processes can exacerbate the conditions associated with dangerous fire behavior. Additionally, understanding the combined effects of heat, moisture, and aerosols on cloud microphysics is important for a range of weather and climate processes, including in relation to improved modeling and prediction capabilities. It is essential to fully explore events such as these to properly characterize the fire behavior, pyroCb dynamics, and resultant influence on conditions in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere (UTLS). It is also important to accurately characterize this transport process so that cloud, chemistry, and climate models have a firm basis on which to evaluate the pyrogenic source term, pathway from the boundary layer through cumulus cloud, and exhaust from the convective column.[20]

Since the discovery of smoke in the stratosphere and the pyroCb, only a small number of individual case studies and modeling experiments have been performed. Hence, there is still much to be learned about the pyroCb and its importance. With this work scientists have attempted to reduce the unknowns by revealing several additional occasions when pyroCbs were either a significant or sole cause for the type of stratospheric pollution usually attributed to volcanic injections.[19]

City firestorms

The same underlying combustion physics can also apply to man-made structures such as cities during war or natural disaster.

Firestorms are thought to have been part of the mechanism of large urban fires, such as accompanied the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. Genuine firestorms are occurring more frequently in California wildfires, such as the 1991 wildfire disaster in Oakland, California, and the October 2017 Tubbs Fire in Santa Rosa, California.[22]

During the July–August 2018 Carr Fire, a deadly fire vortex equivalent in size and strength to an EF-3 tornado spawned during the firestorm in Redding, California and caused tornado-like wind damage.[23][24] Another wildfire which may be characterized as a firestorm was the Camp Fire, which at one point travelled at a speed of up to 76 acres per minute, completely destroying the town of Paradise, California within 24 hours on November 8, 2018.[25]

Firestorms were also created by the firebombing raids of World War II in cities like Hamburg and Dresden.[26] Of the two nuclear weapons used in combat, only Hiroshima resulted in a firestorm.[27] In contrast, experts suggest that due to the nature of modern U.S. city design and construction, a firestorm is unlikely after a nuclear detonation.[28]

| City / event | Date of the firestorm | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bombing of Hamburg in World War II (Germany)[26] | 27 July 1943 | 46,000 dead.[29] A firestorm area of approximately 4.5 square miles (12 km2) was reported at Hamburg.[30] |

| Bombing of Kassel in World War II (Germany) | 22 October 1943 | 9,000 dead. 24,000 dwellings destroyed. Area burned 23 square miles (60 km2); the percentage of this area which was destroyed by conventional conflagration and that destroyed by firestorm is unspecified.[31] Although a much larger area was destroyed by fire in Kassel than even Tokyo and Hamburg, the city fire caused a smaller less extensive firestorm than that at Hamburg.[32] |

| Bombing of Darmstadt in World War II (Germany) | 11 September 1944 | 8,000 dead. Area destroyed by fire 4 square miles (10 km2). Again the percentage of this which was done by firestorm remains unspecified. 20,000 dwellings and one chemical works destroyed and industrial production reduced.[31] |

| Bombing of Dresden in World War II (Germany)[26] | 13–15 February 1945 | From 22,700[33] to 25,000 people[34] were killed. A firestorm area of approximately 8 square miles (21 km2) was reported at Dresden.[30] The attack was centered on the readily identifiable Ostragehege sports stadium.[35] |

| Bombing of Tokyo in World War II (Japan) | 9–10 March 1945 | The firebombing of Tokyo started many fires which converged into a devastating conflagration covering 16 square miles (41 km2). Although often described as a firestorm event,[36][37] the conflagration did not generate a firestorm as the high prevailing surface winds gusting at 17 to 28 mph (27 to 45 km/h) at the time of the fire overrode the fire's ability to form its own wind system.[38] These high winds increased by about 50% the damage done by the incendiary bombs.[39] There were 267,171 buildings destroyed, and between 83,793[40] and 100,000 killed,[41] making this the most lethal air raid in history, with destruction to life and property greater than that caused by the use of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[42][43] Prior to the attack, the city had the highest population density of any industrial city in the world.[44] |

| Bombing of Ube, Yamaguchi in World War II (Japan) | 1 July 1945 | A momentary firestorm of about 0.5 square miles (1.3 km2) was reported at Ube, Japan.[30] The reports that the Ube bombing produced a firestorm, along with computer modelling,[citation needed] have set one of the four physical conditions which a city fire must meet to have the potential of developing true firestorm effects, as the size of the Ube firestorm is the smallest ever confirmed. Glasstone and Dolan:

|

| Atomic bombing of Hiroshima in World War II (Japan) | 6 August 1945 | Firestorm covering 4.4 square miles (11 km2).[46] No estimate can be given of the number of fire deaths, for the fire area was largely within the blast damage region.[47] |

Firebombing

Firebombing is a technique designed to damage a target, generally an urban area, through the use of fire, caused by incendiary devices, rather than from the blast effect of large bombs. Such raids often employ both incendiary devices and high explosives. The high explosive destroys roofs, making it easier for the incendiary devices to penetrate the structures and cause fires. The high explosives also disrupt the ability of firefighters to douse the fires.[26]

Although incendiary bombs have been used to destroy buildings since the start of gunpowder warfare, World War II saw the first use of strategic bombing from the air to destroy the ability of the enemy to wage war. London, Coventry, and many other British cities were firebombed during the Blitz. Most large German cities were extensively firebombed starting in 1942, and almost all large Japanese cities were firebombed during the last six months of World War II. As Sir Arthur Harris, the officer commanding RAF Bomber Command from 1942 through to the end of the war in Europe, pointed out in his post-war analysis, although many attempts were made to create deliberate man-made firestorms during World War II, few attempts succeeded:

"The Germans again and again missed their chance, ...of setting our cities ablaze by a concentrated attack. Coventry was adequately concentrated in point of space, but all the same there was little concentration in point of time, and nothing like the fire tornadoes of Hamburg or Dresden ever occurred in this country. But they did do us enough damage to teach us the principle of concentration, the principle of starting so many fires at the same time that no fire fighting services, however efficiently and quickly they were reinforced by the fire brigades of other towns could get them under control."

— Arthur Harris, [26]

According to physicist David Hafemeister, firestorms occurred after about 5% of all fire-bombing raids during World War II (but he does not explain if this is a percentage based on both Allied and Axis raids, or combined Allied raids, or U.S. raids alone).[48] In 2005, the American National Fire Protection Association stated in a report that three major firestorms resulted from Allied conventional bombing campaigns during World War II: Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo.[36] They do not include the comparatively minor firestorms at Kassel, Darmstadt or even Ube into their major firestorm category. Despite later quoting and corroborating Glasstone and Dolan and data collected from these smaller firestorms:

based on World War II experience with mass fires resulting from air raids on Germany and Japan, the minimum requirements for a firestorm to develop are considered by some authorities to be the following: (1) at least 8 pounds of combustibles per square foot of fire area (40 kg per square meter), (2) at least half of the structures in the area on fire simultaneously, (3) a wind of less than 8 miles per hour at the time, and (4) a minimum burning area of about half a square mile.

— Glasstone and Dolan (1977).[10]

21st-century cities in comparison to World War II cities

| City | Population in 1939 | American tonnage | British tonnage | Total tonnage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berlin | 4,339,000 | 22,090 | 45,517 | 67,607 |

| Hamburg | 1,129,000 | 17,104 | 22,583 | 39,687 |

| Munich | 841,000 | 11,471 | 7,858 | 19,329 |

| Cologne | 772,000 | 10,211 | 34,712 | 44,923 |

| Leipzig | 707,000 | 5,410 | 6,206 | 11,616 |

| Essen | 667,000 | 1,518 | 36,420 | 37,938 |

| Dresden | 642,000 | 4,441 | 2,659 | 7,100 |

Unlike the highly combustible World War II cities that firestormed from conventional and nuclear weapons, a FEMA report suggests that due to the nature of modern U.S. city design and construction, a firestorm is unlikely to occur even after a nuclear detonation[28] because highrise buildings do not lend themselves to the formation of firestorms because of the baffle effect of the structures,[27] and firestorms are unlikely in areas whose modern buildings have totally collapsed, with the exceptions of Tokyo and Hiroshima, because of the nature of their densely-packed "flimsy" wooden buildings in World War II.[47][50]

There is also a sizable difference between the fuel loading of World War II cities that firestormed and that of modern cities, where the quantity of combustibles per square meter in the fire area in the latter is below the necessary requirement for a firestorm to form (40 kg/m2).[51][52] Therefore, firestorms are not to be expected in modern North American cities after a nuclear detonation, and are expected to be unlikely in modern European cities.[53]

Similarly, one reason for the lack of success in creating a true firestorm in the bombing of Berlin in World War II was that the building density in Berlin was too low to support easy fire spread from building to building. Another reason was that much of the building construction was newer and better than in most of the old German city centers. Modern building practices in the Berlin of World War II led to more effective firewalls and fire-resistant construction. Mass firestorms never proved to be possible in Berlin. No matter how heavy the raid or what kinds of firebombs were dropped, no true firestorm ever developed.[54]

Nuclear weapons in comparison to conventional weapons

The incendiary effects of a nuclear explosion do not present any especially characteristic features. In principle, the same overall result with respect to destruction of life and property can be achieved by the use of conventional incendiary and high-explosive bombs.[55] It has been estimated, for example, that the same fire ferocity and damage produced at Hiroshima by one 16-kiloton nuclear bomb from a single B-29 could have instead been produced by about 1,200 tons/1.2 kilotons of incendiary bombs from 220 B-29s distributed over the city; for Nagasaki, a single 21 kiloton nuclear bomb dropped on the city could have been estimated to be caused by 1,200 tons of incendiary bombs from 125 B-29s.[55][56][57]

It may seem counterintuitive that the same amount of fire damage caused by a nuclear weapon could have instead been produced by smaller total yield of thousands of incendiary bombs; however, World War II experience supports this assertion. For example, although not a perfect clone of the city of Hiroshima in 1945, in the conventional bombing of Dresden, the combined Royal Air Force (RAF) and United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) dropped a total of 3441.3 tons (approximately 3.4 kilotons) of ordnance (about half of which was incendiary bombs) on the night of 13–14 February 1945, and this resulted in "more than" 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2) of the city being destroyed by fire and firestorm effects according to one authoritative source,[58] or approximately 8 square miles (21 km2) by another.[30]

In total about 4.5 kilotons of conventional ordnance was dropped on the city over a number of months during 1945 and this resulted in approximately 15 square miles (39 km2) of the city being destroyed by blast and fire effects.[59] During the Operation MeetingHouse firebombing of Tokyo on 9–10 March 1945, 279 of the 334 B-29s dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary and high-explosive bombs on the city, resulting in the destruction of over 10,000 acres of buildings—16 square miles (41 km2), a quarter of the city.[60][61]

In contrast to these raids, when a single 16-kiloton nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, 4.5 square miles (12 km2) of the city was destroyed by blast, fire, and firestorm effects.[47] Similarly, Major Cortez F. Enloe, a surgeon in the USAAF who worked with the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS), said that the 21-kiloton nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki did not do as much fire damage as the extended conventional airstrikes on Hamburg.[62]

- Hiroshima after the bombing and firestorm.

- Wind blowing the smoke plume inland during the 26 May 1945 firebombing raid on Tokyo

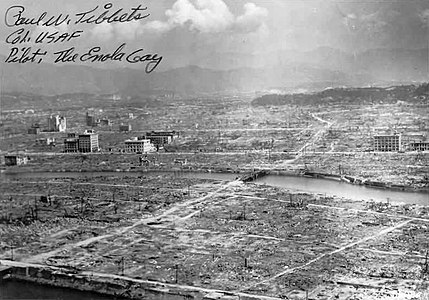

- Hiroshima aftermath. Despite a true firestorm developing, reinforced concrete buildings, as in Tokyo, similarly remained standing. Signed by the Enola Gay pilot, Paul W. Tibbets.

- This Tokyo residential section was virtually destroyed. All that remained standing were concrete buildings in this photograph.

American historian Gabriel Kolko also echoed this sentiment:

During November 1944 American B-29's began their first incendiary bomb raids on Tokyo, and on 9 March 1945, wave upon wave dropped masses of small incendiaries containing an early version of napalm on the city's population....Soon small fires spread, connected, grew into a vast firestorm that sucked the oxygen out of the lower atmosphere. The bomb raid was a 'success' for the Americans; they killed 125,000 Japanese in one attack. The Allies bombed Hamburg and Dresden in the same manner, and Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, and Tokyo again on May 24....in fact the atomic bomb used against Hiroshima was less lethal than massive fire bombing....Only its technique was novel—nothing more....There was another difficulty posed by mass conventional bombing, and that was its very success, a success that made the two modes of human destruction qualitatively identical in fact and in the minds of the American military. "I was a little fearful", [Secretary of War] Stimson told [President] Truman, "that before we could get ready the Air Force might have Japan so thoroughly bombed out that the new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength." To this the President "laughed and said he understood."[63]

This break from the linear expectation of more fire damage to occur after greater explosive yield is dropped can be easily explained by two major factors. First, the order of blast and thermal events during a nuclear explosion is not ideal for the creation of fires. In an incendiary bombing raid, incendiary weapons followed after high-explosive blast weapons were dropped, in a manner designed to create the greatest probability of fires from a limited quantity of explosive and incendiary weapons. The so-called two-ton "cookies",[35] also known as "blockbusters", were dropped first and were intended to rupture water mains, as well as to blow off roofs, doors, and windows, creating an air flow that would feed the fires caused by the incendiaries that would then follow and be dropped, ideally, into holes created by the prior blast weapons, such as into attic and roof spaces.[64][65][66]

On the other hand, nuclear weapons produce effects that are in the reverse order, with thermal effects and "flash" occurring first, which are then followed by the slower blast wave. It is for this reason that conventional incendiary bombing raids are considered to be a great deal more efficient at causing mass fires than nuclear weapons of comparable yield. It is likely this led the nuclear weapon effects experts Franklin D'Olier, Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan to state that the same fire damage suffered at Hiroshima could have instead been produced by about 1 kiloton/1,000 tons of incendiary bombs.[55][56]

The second factor explaining the non-intuitive break in the expected results of greater explosive yield producing greater city fire damage is that city fire damage is largely dependent not on the yield of the weapons used, but on the conditions in and around the city itself, with the fuel loading per square meter value of the city being one of the major factors. A few hundred strategically placed incendiary devices would be sufficient to start a firestorm in a city if the conditions for a firestorm, namely high fuel loading, are already inherent to the city (see Bat bomb).

The Great Fire of London in 1666, although not forming a firestorm due to the single point of ignition, serves as an example that, given a densely packed and predominantly wooden and thatch building construction in the urban area, a mass fire is conceivable from the mere incendiary power of no more than a domestic fireplace. On the other hand, the largest nuclear weapon conceivable (more than a gigaton blast yield)[67] will be incapable of igniting a city into a firestorm if the city's properties, namely its fuel density, are not conducive to one developing. It's worth remembering that such a device would still destroy any city in the world today from its shockwave alone, as well as irradiate the ruins to the point of uninhabitability. A device so large could even vaporize the city (and the crust beneath) all at once without such damage qualifying as a "firestorm".[68]

Despite the disadvantage of nuclear weapons when compared to conventional weapons of lower or comparable yield in terms of effectiveness at starting fires, for the reasons discussed above, one undeniable advantage of nuclear weapons over conventional weapons when it comes to creating fires is that nuclear weapons undoubtedly produce all their thermal and explosive effects in a very short period of time. That is, to use Arthur Harris's terminology, they are the epitome of an air raid guaranteed to be concentrated in "point in time".

In contrast, early in World War II, the ability to achieve conventional air raids concentrated in "point of time" depended largely upon the skill of pilots to remain in formation, and their ability to hit the target whilst at times also being under heavy fire from anti-aircraft fire from the cities below. Nuclear weapons largely remove these uncertain variables. Therefore, nuclear weapons reduce the question of whether a city will firestorm or not to a smaller number of variables, to the point of becoming entirely reliant on the intrinsic properties of the city, such as fuel loading, and predictable atmospheric conditions, such as wind speed, in and around the city, and less reliant on the unpredictable possibility of hundreds of bomber crews acting together successfully as a single unit.

See also

Potential firestorms

Portions of the following fires are often described as firestorms, but that has not been corroborated by any reliable references:

- Great Fire of Rome (64 AD)

- Great Fire of London (1666)

- Great Chicago Fire (1871)

- Peshtigo Fire (1871)

- San Francisco earthquake (1906)

- Great Kantō earthquake (1923)

- Tillamook Burn (1933–1951)

- Second Great Fire of London (1940)

- Ash Wednesday bushfires (1983)

- Yellowstone fires (1988)

- Canberra bushfires (2003)

- Okanagan Mountain Park Fire (2003)

- Black Saturday bushfires (2009)

- Fort McMurray wildfire (2016)

- Predrógâo Grande wildfire (2017)

- Carr Fire (2018)

- 2021 British Columbia wildfires (2021)

References

- ^ Scawthorn, Charles, ed. (2005). Fire following earthquake. Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering monograph. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7844-0739-4.

- ^ Alexander Mckee's Dresden 1945: The Devil's Tinderbox

- ^ "Problems of Fire in Nuclear Warfare (1961)" (PDF). Dtic.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

A fire storm is characterized by strong to gale force winds blowing toward the fire everywhere around the fire perimeter and results from the rising column of hot gases over an intense, mass fire drawing in the cool air from the periphery. These winds blow the fire brands into the burning area and tend to cool the unignited fuel outside so that ignition by radiated heat is more difficult, thus limiting fire spread.

- ^ a b "Problems of fire in Nuclear Warfare 1961" (PDF). Dtic.mil. pp. 8 & 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Weaver & Biko 2002.

- ^ a b Gess & Lutz 2003, p. 234

- ^ Hemphill, Stephanie (27 November 2002). "Peshtigo: A Tornado of Fire Revisited". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

The town was at the center of a tornado of flame. The fire was coming from all directions at once, and the winds were roaring at 100 mph.

- ^ James Killus (16 August 2007). "Unintentional Irony: Firestorms". Unintentional-irony.blogspot.no. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Chris Cavanagh. "Thermal Radiation Damage". Holbert.faculty.asu.edu. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 299, 300, ¶ 7.58.

- ^ "Direct Effects of Nuclear Detonations" (PDF). Dge.stanford.edu. 11 May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ a b Michael Finneran (19 October 2010). "Fire-Breathing Storm Systems". NASA. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 299, 300, ¶ 7.59.

- ^ Kartman & Brown 1971, p. 48.

- ^ "Atmospheric Processes : Chapter=4" (PDF). Globalecology.stanford.edu. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Fromm, M.; Stocks, B.; Servranckx, R.; et al. (2006). "Smoke in the Stratosphere: What Wildfires have Taught Us About Nuclear Winter". Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 87 (52 Fall Meet. Suppl): Abstract U14A–04. Bibcode:2006AGUFM.U14A..04F. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Fromm, M.; Tupper, A.; Rosenfeld, D.; Servranckx, R.; McRae, R. (2006). "Violent pyro-convective storm devastates Australia's capital and pollutes the stratosphere". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (5): L05815. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..33.5815F. doi:10.1029/2005GL025161. S2CID 128709657.

- ^ Riebeek, Holli (31 August 2010). "Russian Firestorm: Finding a Fire Cloud from Space: Feature Articles". Earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d Fromm, Michael; Lindsey, Daniel T.; Servranckx, René; Yue, Glenn; Trickl, Thomas; Sica, Robert; Doucet, Paul; Godin-Beekmann, Sophie (2010). "The Untold Story of Pyrocumulonimbus". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 91 (9): 1193–1210. Bibcode:2010BAMS...91.1193F. doi:10.1175/2010bams3004.1.

- ^ a b c d Dowdy, Andrew J.; Fromm, Michael D.; McCarthy, Nicholas (27 July 2017). "Pyrocumulonimbus lightning and fire ignition on Black Saturday in southeast Australia". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 122 (14): 2017JD026577. Bibcode:2017JGRD..122.7342D. doi:10.1002/2017jd026577. ISSN 2169-8996. S2CID 134053333.

- ^ Werth, Paul; et al. (March 2016). "Specific Effects of Fire Interaction" (PDF). Synthesis of Knowledge of Extreme Fire Behavior. 2: 88–97.

- ^ Peter Fimrite (19 October 2017). "'Like a blowtorch': Powerful winds fueled tornadoes of flame in Tubbs Fire". SFGate.

- ^ "How a weird fire vortex sparked a meteorological mystery". www.nationalgeographic.com. 19 December 2018. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019.

- ^ Jennifer Calfas (16 August 2018). "New Horrifying Details Released About Fire Tornado That Killed California Firefighter". Time.

- ^ "The California Report: Report Details Injuries to 5 Firefighters in Camp Fire, Compares Blaze's Ferocity to WWII Attack". KQED News. 14 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 2005, p. 83

- ^ a b American National Fire Protection Association 2005, p. 68.

- ^ a b "Page 24 of Planning Guidance for response to a nuclear detonation. Written with the collaboration of FEMA & NASA to name a few agencies" (PDF). Hps.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Frankland & Webster 1961, pp. 260–261.

- ^ a b c d "Exploratory Analysis of Fire storms". Dtic.mil. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b The Cold War Who won? pp. 82–88 Chapter 18 https://www.scribd.com/doc/49221078/18-Fire-in-WW-II

- ^ "Campaign Diary October 1943". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- ^ Shortnews staff (14 April 2010), Alliierte Bombenangriffe auf Dresden 1945: Zahl der Todesopfer korrigiert (in German), archived from the original on 21 February 2014

- ^ Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Schönherr, Nicole; Widera, Thomas, eds. (2010), Die Zerstörung Dresdens: 13. bis 15. Februar 1945. Gutachten und Ergebnisse der Dresdner Historikerkommission zur Ermittlung der Opferzahlen. (in German), V&R Unipress, pp. 48, ISBN 978-3899717730

- ^ a b De Bruhl (2006), pp. 209.

- ^ a b American National Fire Protection Association 2005, p. 24.

- ^ David McNeill (10 March 2005). "The night hell fell from the sky (Korean translation available)". Japan Focus. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Rodden, Robert M.; John, Floyd I.; Laurino, Richard (May 1965). Exploratory analysis of Firestorms., Stanford Research Institute, pp. 39–40, 53–54. Office of Civil Defense, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Werrell, Kenneth P (1996). Blankets of Fire. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-56098-665-2.

- ^ Michael D. Gordin (2007). Five days in August: how World War II became a nuclear war. Princeton University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-691-12818-4.

- ^ Technical Sergeant Steven Wilson (25 February 2010). "This month in history: The firebombing of Dresden". Ellsworth Air Force Base. United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II: Combat Chronology. March 1945. Archived 2 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Historical Studies Office. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ^ Freeman Dyson. (1 November 2006). "Part I: A Failure of Intelligence". Technology Review. MIT. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Mark Selden. A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from the Pacific War to Iraq. Japan Focus, 2 May 2007 Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 299, 200, ¶ 7.58.

- ^ McRaney & McGahan 1980, p. 24.

- ^ a b c "Exploratory Analysis of Fire Storms". Dtic.mil. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Hafemeister 1991, p. 24 (¶ 2nd to last).

- ^ Angell (1953)

- ^ Oughterson, A. W.; Leroy, G. V.; Liebow, A. A.; Hammond, E. C.; Barnett, H. L.; Rosenbaum, J. D.; Schneider, B. A. (19 April 1951). "Medical Effects Of Atomic Bombs The Report Of The Joint Commission For The Investigation Of The Effects Of The Atomic Bomb In Japan Volume 1". Osti.gov. doi:10.2172/4421057.

- ^ "On page 31 of Exploratory analysis of Firestorms. It was reported that the weight of fuel per acre in several California cities is 70 to 100 tons per acre. This amounts to about 3.5 to 5 pounds per square foot of fire area (~20 kg per square meter)". Dtic.mil. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "Canadian cities fuel loading from Validation of Methodologies to Determine Fire Load for Use in Structural Fire Protection" (PDF). Nfpa.org. 2011. p. 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

The mean fire load density in buildings, from the most accurate weighing method, was found to be 530 MJ/m^2. The fire load density of a building can be directly converted into building fuel load density as outlined in the document with Wood having a specific energy of ~18 MJ/kg. Thus 530/18 = 29 kg/m^2 of building fuel loading. This, again, is below the necessary 40kg/m^2 needed for a firestorm, even before the open spaces between buildings are included/before the corrective builtupness factor is applied and the all-important fire area fuel loading is found

- ^ "Determining Design Fires for Design-level and Extreme Events, SFPE 6th International Conference on Performance-Based Codes and Fire Safety Design Methods" (PDF). Fire.nist.gov. 14 June 2006. p. 3. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

The .90 fractile of buildings in Switzerland (that is 90% of buildings surveyed fall under the stated fire loading figure) had 'fuel loadings below the crucial 8 lb/sqft or 40 kg/m^2 density'. The .90 fractile is found by multiplying the mean value found by 1.65. Keep in mind, none of these figures even take the builtupness factor into consideration, thus the all-important fire area fuel loading is not presented, that is, the area including the open spaces between buildings. Unless otherwise stated within the publications, the data presented is individual building fuel loadings and not the essential fire area fuel loadings. As a point of example, a city with buildings of a mean fuel loading of 40kg/m^2 but with a builtupness factor of 70%, with the rest of the city area covered by pavements, etc., would have a fire area fuel loading of 0.7*40kg/m^2 present, or 28 kg/m^2 of fuel loading in the fire area. As the fuel load density publications generally do not specify the builtupness factor of the metropolis where the buildings were surveyed, one can safely assume that the fire area fuel loading would be some factor less if builtupness was taken into account

- ^ "'The Cold War: Who won? This ebook cites the firebombing reported in Horatio Bond's book Fire in the Air War National Fire Protection Association, 1946, p. 125 – Why didn't Berlin suffer a mass fire? The table on pg 88 of Cold War: Who Won? was sourced from the same 1946 book by Horatio Bond Fire in the Air War pp. 87, 598". Scribd.com. ASIN B000I30O32. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 299, 300, ¶ 7.61.

- ^ a b D'Olier, Franklin, ed. (1946). United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report (Pacific War). Washington: United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ "United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report". Marshall.csu.edu.au. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

'+would have required 220 B-29s carrying 1,200 tons of incendiary bombs, 400 tons of high-explosive bombs, and 500 tons of anti-personnel fragmentation bombs, if conventional weapons, rather than an atomic bomb, had been used. One hundred and twenty-five B-29s carrying 1,200 tons of bombs (p. 25 ) would have been required to approximate the damage and casualties at Nagasaki. This estimate pre-supposed bombing under conditions similar to those existing when the atomic bombs were dropped and bombing accuracy equal to the average attained by the Twentieth Air Force during the last 3 months of the war

- ^

- Angell (1953) The number of bombers and tonnage of bombs are taken from a USAF document written in 1953 and classified secret until 1978.

- Bomber Command Arthur Harris's report, "Extract from the official account of Bomber Command by Arthur Harris, 1945" Archived 3 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, National Archives, Catalogue ref: AIR 16/487, which states that more than 1,600 acres (6.5 km2) were destroyed.

- ^ Angell (1953) The number of bombers and tonnage of bombs are taken from a USAF document written in 1953 and classified secret until 1978. Also see Taylor (2005), front flap, which gives the figures 1,100 heavy bombers and 4,500 tons.

- ^ Laurence M. Vance (14 August 2009). "Bombings Worse than Nagasaki and Hiroshima". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Joseph Coleman (10 March 2005). "1945 Tokyo Firebombing Left Legacy of Terror, Pain". CommonDreams.org. Associated Press. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ "News in Brief". Flight: 33. 10 January 1946.

- ^ Kolko, Gabriel (1990) [1968]. The Politics of War: The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1943–1945. Pantheon Books. pp. 539–540. ISBN 9780679727576.

- ^ De Bruhl (2006), pp. 210–211.

- ^ Taylor, Bloomsbury 2005, pp. 287, 296, 365.

- ^ Longmate (1983), pp. 162–164.

- ^ "In Search of a Bigger Boom". Nuclear Secrecy Blog. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Kurzgesagt: What If We Detonated All Nuclear Bombs at Once?". YouTube. 31 March 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

Further reading

- American National Fire Protection Association (2005). Scawthorn, Charles; Eidinger, John M.; Schiff, Anshel J. (eds.). Fire Following Earthquake (Technical report). Issue 26 of Monograph (American Society of Civil Engineers. Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering), American Society of Civil Engineers Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering (illustrated ed.). ASCE Publications. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7844-0739-4.

- De Bruhl, Marshall (2006). Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden. Random House. ISBN 978-0679435341.

- Gess, Denise; Lutz, William (2003) [2002]. Firestorm at Peshtigo: A Town, Its People, and the Deadliest Fire in American History. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-7293-8.

- Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip J., eds. (1977). "Chapter VII: Thermal Radiation and Its Effects" (PDF). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons (Third ed.). United States Department of Defense and the Energy Research and Development Administration. pp. 299, 300, § "Mass Fires" ¶7.58, 7.59 and § "The Nuclear Bomb as an Incendiary Weapon" ¶7.61.

- Frankland, Noble; Webster, Charles (1961). The Strategic Air Offensive Against Germany, 1939–1945, Volume II: Endeavour, Part 4. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 260–261.

- Hafemeister, David W, ed. (1991). Physics and Nuclear Arms Today. Issue 4 of Readings from Physics Today (Illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-88318-640-4.

- Harris, Arthur (2005). Bomber Offensive (First, Collins 1947 ed.). Pen & Sword military classics. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-84415-210-0.

- Kartman, Ben; Brown, Leonard (1971). Disaster!. Essay Index Reprint Series. Ayer Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8369-2280-6.

- McRaney, W.; McGahan, J. (6 August 1980). Radiation dose reconstruction U.S. occupation forces in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, 1945–1946 (DNA 5512F) – Final Report for Period 7 March 1980 – 6 August 1980 (PDF) (Technical report). Science Applications, Inc. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2006.

- Neutzner, Matthias; Schönherr, Nicole; von Plato, Alexander; Schnatz, Helmut (2010). Abschlussbericht der Historikerkommission zu den Luftangriffen auf Dresden zwischen dem 13. und 15. Februar 1945 (PDF) (Report). Landeshauptstadt Dresden. p. 70. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- Pyne, Stephen J. (2001). Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910. Viking-Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0-670-89990-6.

- Weaver, John; Biko, Dan (2002). "Firestorm Induced Tornado". Retrieved 3 February 2012.