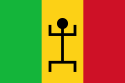

Mali Federation

Mali Federation Fédération du Mali (French) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959–1960 | |||||||||||||

| Motto: Un Peuple, Un But, Une Foi | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: National Anthem of The Mali Federation | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Status | Territory of France (1959–1960) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Dakar | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic, French | ||||||||||||

| Government | Federal republic within French Community (until 20 June 1960) | ||||||||||||

| High Commissioner | |||||||||||||

• 1959–1960 | Jean Charles Sicurani | ||||||||||||

| Premier and President (after 20 June 1960) | |||||||||||||

• 1959–1960 | Modibo Keïta | ||||||||||||

| Vice Premier | |||||||||||||

• 1959–1960 | Mamadou Dia | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Federal assembly[1] | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Decolonization of Africa | ||||||||||||

| 4 April 1959 | |||||||||||||

| 20 June 1960 | |||||||||||||

| 20 August 1960[2] | |||||||||||||

| Currency | CFA franc | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Mali Senegal | ||||||||||||

The Mali Federation (Arabic: اتحاد مالي) was a federation in West Africa linking the French colonies of Senegal and the Sudanese Republic (or French Sudan) for two months in 1960.[2] It was founded on 4 April 1959 as a territory with self-rule within the French Community and became independent after negotiations with France on 20 June 1960. Two months later, on 19 August 1960, the Sudanese Republic leaders in the Mali Federation mobilized the army, and Senegal leaders in the federation retaliated by mobilizing the gendarmerie (national police); this resulted in a tense stand-off, and led to the withdrawal from the federation by Senegal the next day. The Sudanese Republic officials resisted this dissolution, cut off diplomatic relations with Senegal, and defiantly changed the name of their country to Mali. For the brief existence of the Mali Federation, the premier was Modibo Keïta, who would later become the first President of Mali, and its government was based in Dakar, the eventual capital of Senegal.

President and Prime Minister

| Name

(Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel Ouezzin Coulibaly | 1958 | 1958 | |

| Modibo Keïta | 1958 | 1963 | |

| Kwame Nkrumah | 23 November 1958 | 1958 | |

| Ahmed Sékou Touré | 1958 | 1958 | |

| Auguste Denise | 1958 | 1958 | |

| Félix Houphouët-Boigny | 1958 | 1958 | |

| Modibo Keïta | 1958 | 1960 | |

| Mamadou Dia | 1960 | 1960 | |

| Léopold Sédar Senghor | 1960 | 1960 | |

| Maurice Yaméogo | 1960 | 1960 | |

| Sourou-Migan Apithy | 1960 | 1960 | |

| Hubert Maga | 1960 | 1960 |

Background

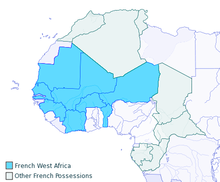

After World War II, the colonies of French West Africa began pushing significantly for increased self-determination and to redefine their colonial relationships with France. Following the May 1958 crisis, the colonies of French West Africa were given the chance to vote for immediate independence or to join a reorganized French Community (an arrangement which would grant the colonies some self-determination while maintaining ties to France). Only Guinea voted for full independence and the other colonies of French West Africa voted to join the French Community.[3]

In the 1958 election to decide the issue of independence, two major parties split the countries of west Africa: the African Democratic Rally (French: Rassemblement Démocratique Africain, commonly known as the RDA) and the African Regroupment Party (French: Parti du Regroupement Africain, commonly known as the PRA). The two regional groupings of parties struggled against one another on the issue of independence and the extent of ties with France. The RDA was the governing party in the Ivory Coast colony, the French Sudan colony, and Guinea while the PRA was a major governing party in Senegal and had sizable majorities in many countries. The two parties also were part of coalition governments in French Upper Volta, Niger, and French Dahomey. Both two parties struggled with each other to shape the political future of the region, Mauritania often became a neutral party that would break any deadlocks. The vote of 1958 revealed a number of divisions within the parties.[4] The RDA held a congress on 15 November 1958 to discuss the recent election results and the division became clear with Modibo Keïta from French Sudan and Doudou Gueye from Senegal arguing for primary federation, which would include France and the colonies in a unified system, and Félix Houphouët-Boigny of the Ivory Coast dismissing that idea. The resulting deadlock was so severe that the meeting was officially said to have never taken place.[5]

Formation

In late November 1958, French Sudan, Senegal, Upper Volta and Dahomey all declared the intention to join the French Community and form a federation linking the four colonies together. French Sudan and Senegal, despite longstanding divisions between their main political parties,[6] were the most enthusiastic pushers for the federation, while Dahomey and Upper Volta were more hesitant in their desire to join the federation.[7] French Sudan called for representatives of each of the four countries (and Mauritania as an observer) to Bamako on 28 to 30 December to discuss the formation of the federation.[8] French Sudan and Senegal were the leaders at the congress with Modibo Keïta named the president of the meeting and Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal being the key leader on many issues, including developing the name Mali Federation for the proposed union.[9]

Although Upper Volta and Dahomey declared formal support for the federation, and Upper Volta even approved the Mali Federation Constitution on 28 January 1959, political pressure from France and the Ivory Coast, both of which opposed the federation although for very different reasons, resulted in neither ratifying a constitution that would include them within the federation.[3][10] The result is that only the colonies of French Sudan (now called the Sudanese Republic) and Senegal were engaged in the discussions of the formation of the federation by 1959.[6]

Elections in March 1959 in both French Sudan and Senegal cemented the power of the major parties pushing for the formation of a federation. Keïta's Union Soudanaise-Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (US-RDA) won 76% of the votes in French Sudan and all of the seats in the territorial assembly. Senghor's Union Progressiste Sénégalaise (UPS) won 81% of the vote and all of the seats in Senegal's territorial assembly.[11] Although Senghor won the elections by a large margin, some conservative Islamist marabouts supported the candidacy of Cheikh Tidjane Sy. That challenge to Senghor's party showed some of the weakness in Senghor's domestic political base and required a complex system of alliances with various domestic constituencies, both of which would become important as the federation progressed. Sy was arrested on election day because of some rioting, which was blamed on his party.[11]

After the elections, the assemblies of Senegal and French Sudan approved the federation and began the process of constructing a political system to unite the two colonies. That involved three different political projects with the principle of parity (even representation from both colonies) enshrined in each' a federal government, united social movements (a labour and youth movement) and a shared political party for both countries.[12] The federal government would have a federal assembly composed of 20 members from each of the colonies (40 in total), a President (set to be elected in August 1960) and six federal ministers (with 3 from each colony). Until a president was elected, the premier of the Mali Federation was to be Keïta and the vice-premier (and the person in charge of the armed forces) was to be Mamadou Dia from Senegal.[12][13][6] Furthermore, as part of the parity principle, any legislative initiatives required a signature by both the premier (then later the president) and the minister responsible for that issue.[12] The colonies were to share the import and export taxes raised in the port of Dakar between them to the advantage of French Sudan, which had almost a third of its 1959 budget provided by that tax income.[14]

At the same time, the Mali federation sought to create unified social organisations to facilitate the union between the countries. That involved creating labour movements and youth movements to operate at both the federal and national levels and a unified political party.[12] The political party was the major project as the ruling parties in both colonies combined to form the Parti de la Fédération Africaine (PFA). It was organised separately from the federal government but with many of the same members and leaders. Senghor was the party president and Keïta was the secretary general. In addition, to have a regional influence, Djibo Bakary of Niger and Emile Zinsou of Dahomey were named the vice-presidents of the party.[15] As articulated at the first PFA congress in July 1959 by Senghor, it would be the single political party in the country and aim to unite across the different ethnic groups in the territory.[16]

In December 1959, France and the Mali Federation began negotiations regarding independence and sovereignty of the federation. The negotiations were formally started when French President Charles de Gaulle visited Bamako on 13 December 1959, and lasted until March 1960. Although the French had resisted the Mali Federation, but after the two countries showed willingness to remain within the French Community and the franc zone and to keep the French military bases within its territory, the French supported the formation of the federation. The negotiations agreed upon 20 June 1960 for the formal independence day of the Mali Federation.[17]

Political tension and dissolution

Tensions quickly arose within the Mali Federation as planning for the implementation of the federation began in 1959 and early 1960. Unlike some other areas of French West Africa, French Sudan and Senegal did not have significant amounts of migration or intercultural movement during the colonial period (although they were linked together in French economic policy and linked by a key railway).[18] More serious than ethnic or linguistic differences, however, were some of the results of the design of the federation. While the parity principle allowed both countries to join together without fears of losing their sovereignty, it also resulted in political spillover, as political disputes moved from one arena to another.[19] Similarly, the PFA tried to combine two political parties, which were in very different situations with the French Sudan political party, having achieved political dominance, but the Senegal party needed an elaborate and complex arrangement of alliances to maintain authority.[20] In addition, some of the aspects left vague in the first discussions became key issues of debate between the political leaders of Senegal and French Sudan as their articulation became more important, including armed forces, development of an indigenous bureaucracy, the strength of the federal government and the precise relationship with France.[13][21] Finally, different visions for the colony between Senghor and Keïta proved very difficult to mediate: Keïta, after the dissolution of the federation, claimed that he pursued socialism, but Senghor pushed a bourgeoisie agenda.[2]

The disagreements remained manageable until April 1960 after negotiations with France for recognition of independence had finished. French Sudan began to push for a single executive in the federation with significant independent authority. Senegal preferred to maintain the parity principle as it had been developed in 1959 and to restrain the power of any president.[22] When a PFA congress to decide the issue ended in a deadlock, its members from outside the federation were called in to mediate and they recommended the creation of a single executive to be appointed by an equal number of representatives from Senegal and French Sudan but also that the taxation would no longer be widely shared between the two colonies (a key Senegal position).[23] Although that issue was resolved to the agreement of both parties, a series of misunderstandings quickly followed. When French Sudan attempted to remove a single military base within its territories, it was interpreted as an attempt to eject the French from the entire territory, which was viewed with suspicion by both Senegal and France.[24]

Tensions hit their high point in August 1960 in preparation for the election of the President of the Mali Federation. Cheikh Tidjane Sy, who had been released from prison and became a member of Senghor's political party, approached Senghor and said that he had been approached by representatives from Sudan who had expressed a preference for a Muslim president of the Mali Federation (like Sy) rather than a Catholic president (like Senghor).[25] An investigation by Senghor's political allies found evidence that French Sudan emissaries had visited Sy's uncle, who was a Muslim political leader.[26] About the same time, Keïta, as Premier of the Mali Federation, began meeting formally with many of the Muslim political leaders of Senegal although there is no evidence of any discussion of undermining Senghor's leadership.[26] On 15 August, Senghor, Dia, and other political leaders of Senegal began to work on how to get Senegal out of the federation.[26] Mamadou Dia, as the vice-premier and person in charge of national defense, began surveying the readiness of various military units in case the political situation were to become hostile. Those questions to the various military units resulted in panic by Keïta and the French Sudanese politicians. On 19 August, with reports of Senegalese peasants arming in Dakar, Keïta dismissed Dia as the defense minister, declared a state of emergency, and mobilized the armed forces. Senghor and Dia were able to get a political ally in the military to demobilize the military and then had the national gendarmerie which surrounded Keïta's house and the government offices.[13][27][28]

Senegal declared independence from the Mali Federation at a midnight session on 20 August. There was little violence and the French Sudan officials were sent on a sealed train back to Bamako on 22 August.[29] The federation may have been salvageable in spite of the crisis but by sending Keïta and the others back on a hot, sealed train during August, rather than a plane, led Keïta to declare that the railroad be destroyed at the border after the trip.[30] Independent nations of Senegal and the Republic of Mali were recognized by most countries by mid-September and accepted into the United Nations in late September 1960.[29]

Legacy

Although the Mali Federation existed in name only in Bamako for another month, France and most other nations recognized the two colonies as separate independent countries on 12 September 1960.[31] The Sudanese Union – African Democratic Rally party in French Sudan adopted the slogan "Le Mali Continue" and at a meeting on 22 September the party decided to rename the country Mali and to sever ties with the French Community.[32] The admission to the United Nations for both countries was delayed until late September as a result of the Mali Federation dispute.

Senghor and Keïta both ruled their countries at the time of the split from the Mali Federation and for a number of years: Senghor was president of Senegal from 1960 until 1980 and Keïta from 1960 until 1968. Senghor suffered some domestic challenges after the split from the Mali Federation but after an armed fight between his supporters and those of Mamadou Dia's supporters in 1962, he had largely consolidated his rule.[31] Senghor became very wary of unification efforts after the failed experiment and despite attempts to create other federations in West Africa and with Senegal's neighbours, Senghor often restrained these efforts and they only progressed after his rule.[33] In addition, as the first failed unification experiment in Africa, the Mali Federation served as a lesson in future attempts at unification throughout the continent.[34] Keïta became more assertive with pushing his ideology after the collapse of the federation and refused diplomatic relations with Senegal for many years.[31] Nonetheless, Mali under Keïta still pursued the goal of West African unity but did so in a variety of different international connections.[35] The railroad was reopened on 22 June 1963 and Senghor and Keïta embraced at the border.[36]

See also

References

- ^ World Trade Information Service 1960.

- ^ a b c Hodgkin & Morgenthau 1964, p. 243.

- ^ a b Kurtz 1970, p. 405.

- ^ Foltz 1965, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Hodgkin & Morgenthau 1964, p. 242.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 99.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 100.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 104.

- ^ Foltz 1965, pp. 109–111.

- ^ a b Foltz 1965, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d Foltz 1965, p. 162.

- ^ a b c Imperato 1989, p. 54.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 156.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 165.

- ^ Zolberg 1966, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 168.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 148.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 163.

- ^ Hodgkin & Morgenthau 1964, p. 244.

- ^ Foltz 1965, pp. 169–172.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 169.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 170.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 175.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Foltz 1965, p. 180.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 182.

- ^ Pedler 1979, p. 164.

- ^ a b Foltz 1965, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Pedler 1979, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Foltz 1965, p. 183.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 184.

- ^ Welch 1966, p. 265.

- ^ Kurtz 1970, p. 406.

- ^ Hodgkin & Morgenthau 1964, p. 245.

- ^ Foltz 1965, p. 185.

Bibliography

- Foltz, William J. (1965). From French West Africa to the Mali Federation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hodgkin, Thomas; Morgenthau, Ruth Schacter (1964). "Mali". In James Scott Coleman (ed.). Political Parties and National Integration in Tropical Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 216–258.

- Imperato, Pascal Jame (1989). Mali: A Search for Direction. Boulder, CO.: Westview Press.

- Kurtz, Donn M. (1970). "Political Integration in Africa: The Mali Federation". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 8 (3): 405–424. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00019923. S2CID 154671339.

- Pedler, Frederick (1979). Main Currents of West African History 1940–1978. London: MacMillan Press.

- Welch, Claude E. Jr. (1966). Dream of Unity, Pan-Africanism and Political Unification in West Africa. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- World Trade Information Service. Washington, D.C.: United States Bureau of Foreign Commerce, U.S. Government Printing Office. August 23, 1960. OCLC 29828501 – via Google Books.

- Zolberg, Aristide R. (1966). Creating Political Order: The Party-States of West Africa. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company.