Farm Sanctuary

| |

| Formation | 1986 |

|---|---|

| Founders | Gene Baur and Lorri Houston |

| 51-0292919 | |

| Legal status | 501(c)(3) |

| Purpose | Animal protection |

| Location | |

| Website | www |

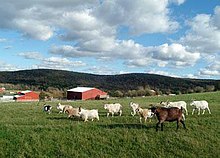

Farm Sanctuary is an American animal protection organization, founded in 1986 as an advocate for farmed animals. It was America's first shelter for farmed animals.[3] It promotes laws and policies that support animal welfare, animal protection, and veganism through rescue, education, and advocacy. Farm Sanctuary houses over 800 cows, chickens, ducks, geese, turkeys, pigs, sheep, and goats at a 300+ acre animal sanctuary in Watkins Glen, New York, and more than 100 animals at its location in Acton, California, near Los Angeles.[4]

The original version of the documentary film Peaceable Kingdom featured Farm Sanctuary and people that work or visit there. The most recent version of the film no longer includes Farm Sanctuary footage. The documentary The Ghosts in Our Machine (2014) has a scene in which Jo-Anne McArthur visits the farm in order to escape the stresses of her work photographing factory farms.

History

Farm Sanctuary was founded in 1986 by Gene Baur and Lorri Houston (then known as Gene and Lorri Bauston). It was originally funded by sales of vegetarian hot dogs at Grateful Dead concerts.[5] The first animal rescued was a sheep named Hilda, who was rescued from a pile of dead animals behind a stockyard.[6][7]

Farm Sanctuary's budget exceeds five million dollars, with funding coming from, among other sources, a donor club named after Hilda.[6] In March 2008, Baur released the book Farm Sanctuary: Changing Hearts and Minds About Animals and Food, documenting the history of the organization.[8] The book reached the Los Angeles Times and Boston Globe bestseller lists.[9] Baur's second book, Living the Farm Sanctuary Life: The Ultimate Guide to Eating Mindfully, Living Longer, and Feeling Better Every Day, coauthored with Gene Stone (author of Forks Over Knives), was published in April 2015 and includes 100 vegan recipes selected by chefs and celebrities.[10] It appeared on Publishers Weekly's bestsellers list.[11]

Legislation and advocacy

Confinement systems

Farm Sanctuary has successfully banned various confinement systems of farm animals by supporting voter referendums. In 2002, Farm Sanctuary was part of a coalition of groups that comprised Floridians for Humane Farms, which sponsored the initiative that amended the Florida Constitution to limit the "cruel and inhumane confinement of pigs during pregnancy." The measure, which passed with 55 percent approval, outlaws caging pigs in gestation stalls, which are metal enclosures that measure two feet across and prevent sows from turning around freely.[citation needed]

In 2006, Arizona residents voted on Proposition 204, which requires that pregnant pigs and calves raised for veal be kept in enclosures large enough that they can turn around and fully extend their limbs by December 31, 2012.[12] A majority of voters, 62 percent, approved the measure, known as the Humane Treatment of Farm Animals Act, which received funding from Farm Sanctuary.[13]

In 2008, Californians voted on Proposition 2, which requires California farmers to provide egg-laying hens, veal calves, and pregnant pigs with housing that gives them enough room to move around beginning January 1, 2015. The law would mostly impact the state's 18 million egg-laying hens.[14] Current[when?] industry standards call for caged hens to get at least 67 square inches of space each, a little less than a regular-size sheet of paper (a sheet of paper is 93.5 square inches), and hens are typically caged in groups of two to eight. Proposition 2 grew into the most expensive animal welfare ballot measure ever, with both sides raising nearly $8 million each.[15] The measure passed with 63.2 percent of the vote.[16][relevant?]

Foie gras

Farm Sanctuary achieved a legislative victory in California when, in September 2004, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed into law Senate Bill 1520, sponsored in part by Farm Sanctuary, which bans the force-feeding of ducks and geese in the production of foie gras and the sale of the product when made from force-fed birds. Both provisions took effect in 2012.[17]

Farm Sanctuary was a vocal supporter of a 2006 Chicago ordinance banning the sale of foie gras.[18] Some establishments found loopholes around the ban, with enforcement proving to be a challenge, as city officials issued warnings to some restaurants and stores, but not fines.[19] A repeal ordinance was later introduced and referred to the Rules Committee – bypassing a Health Committee that had approved the foie gras ban – and was moved to the Council floor without a hearing. The ban was repealed in 2008.[20]

In 2007, Farm Sanctuary launched its "NYC No Foie Gras" campaign, opened a Manhattan office, and hired a full-time development coordinator.[21] Gene Baur said: "New York's a big foodie town, and the restaurant people are pretty well entrenched there, so there's a fair amount of energy that's going to be required in New York."[22] In 2008, Farm Sanctuary said in an official release that three Westside Markets in New York City signed pledges to not sell foie gras, joining more than 50 New York City establishments, 1000 restaurants nationwide, and grocery chains Whole Foods Market and Trader Joe's, all of which have pledged not to sell foie gras.[23] Stephen Starr, owner of 11 restaurants in Philadelphia, removed foie gras from his menus in that city due to what he has called "incredible amount of protest."[24]

Cloning

Farm Sanctuary has been active in the opposition against the United States Food and Drug Administration approval of cloned animals for food. Their opposition is based on health problems in the cloned animals and problems that the maternal carrier has while pregnant with the cloned animal. Farm Sanctuary claims increased rates of hydrops fetalis, Large Offspring Syndrome, and other systemic abnormalities.[25]

Litigation

Farm Sanctuary member Michael Baur, a professor at the Fordham University School of Law, filed an unsuccessful petition in 1998 with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) claiming the consumption of downed animals created a serious risk of transmission of some progressive neurological diseases, including bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or mad cow disease. The subsequent lawsuit, Baur v. Veneman, claimed then-current USDA regulations on downed livestock violated the Federal Meat Inspection Act. Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald of the Southern District of New York dismissed the case for lack of standing in 2002, but the 2nd Circuit reversed Buchwald's decision on December 16, 2003.[26] The 2nd Circuit found it significant that: "the USDA itself as well as other government agencies have recognized that downed cattle are especially susceptible to BSE infection."[27] On December 30, 2003, six days after the USDA announced the first case of mad cow disease in the United States, the agency announced an interim policy against downed cattle entering the food supply (made permanent in 2007), and with the interim policy in place, the case was soon settled.[28] In March 2009, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack announced a final rule to amend federal meat inspection regulations, requiring a complete ban on the slaughter of cattle that become "non-ambulatory disabled" at any point.[29]

Farm Sanctuary was part of a coalition of groups that challenged the New Jersey Department of Agriculture's standards governing the raising, keeping, and marketing of domestic livestock. The case went to the New Jersey Supreme Court, which in its July 30, 2008, ruling unanimously said the Department of Agriculture failed, in part, to carry out its mandate in setting humane standards. The Court further rejected agency regulations that certain mutilations of farmed animals such as castration, debeaking, and toe-trimming are "humane" as long as they are carried out by a "knowledgeable individual" "in a way to minimize pain."[30]

Influence on business

Farm Sanctuary prompted Burger King franchise owner David Kessler to bring a veggie burger to customers in western New York in 1993. Mr. Kessler said that getting corporate approval for his request to test market the Griller "was like turning the RMS Queen Mary around in a bathtub", but that he was able to prove that the veggie burger was very popular.[31] In March 2002, Burger King announced it was adding a veggie burger nationwide to its permanent menu, with Morningstar Farms as its sole supplier.[32]

In March 2007, Wolfgang Puck Companies announced that, with "advice from Farm Sanctuary" they were rolling out a nine-point program aimed at "stopping the worst practices associated with factory farming" at all their ventures, including 14 full-service restaurants and 80 fast casual units. This included only using eggs from cage-free hens not confined to battery cages, and serving all-natural or organic crate-free pork and veal.[33]

In 2007, Farm Sanctuary partnered with Turtle Mountain, a dairy-free ice cream company, and vegan cartoon artist Dan Piraro to promote So Delicious Dairy Free Kidz and the Farm Sanctuary Kidz Club.[34]

Rescue, rehabilitation, and shelter

Farm Sanctuary was one of four animal welfare groups that responded to the Iowa Department of Agriculture's call to help pigs after severe flooding hit the state in the summer of 2008. Iowa is the leading pork-producing state in the U.S. More than 60 pigs ended up at Farm Sanctuary's Watkins Glen, New York shelter.[35] Farm Sanctuary documented the relief efforts in a blog entitled "2008 Midwest Flood Pig Rescue."[36]

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Farm Sanctuary rescued more than 700 chickens from a broiler factory in Mississippi that had been hit by a tornado. Susie Coston, the shelter director in Watkins Glen, New York, said: "The animals at these facilities are raised in warehouses and many farms have over 500,000 birds at one time. When they were hit by storms, the majority of the birds were bulldozed, some alive, into mass graves." In addition to factory farms, the Watkins Glen sanctuary receives animals from neglect cases, starvation cases, and New York City markets.[37] The facility holds tours May through October, and there are three vegan bed-and-breakfast cabins for overnight visitors.[38] It also has an "Adopt-a-Farm Animal" program where sponsors can pay for the food and care of an animal without taking him/her home.[39] Farm Sanctuary also adopts out turkeys into private homes.[40]

On January 26, 2009, Farm Sanctuary launched "Sanctuary Tails", a blog authored by national shelter director Susie Coston and California shelter director Leanne Cronquist, about the organization's efforts to rescue, rehabilitate, and provide daily care for farm animals.[41]

Since 1993, Farm Sanctuary had maintained a shelter in Orland, California, where it housed farm animals and provided tours, but the Orland shelter closed in 2018.[42] On September 14, 2011, Farm Sanctuary took over administration of the Animal Acres farm animal shelter in Acton, California. Animal Acres, which had been founded by Farm Sanctuary co-founder Lorri Houston, had come under financial pressures caused by the soft economy and consequent reduced donations. Farm Sanctuary had been providing volunteers to assist at Animal Acres since April 2011.[43] Bufflehead Farm, a 12-acre (4.9 ha) sanctuary farm in Middletown, New Jersey, owned by Jon Stewart, is affiliated with Farm Sanctuary.[44]

Controversy

In 1993, Farm Sanctuary was listed as an organization that has "claimed to have perpetrated acts of extremism in the United States" in the Report to Congress on the Extent and Effects of Domestic and International Terrorism on Animal Enterprises.[45] The Department of Justice later retracted the inclusion of Farm Sanctuary in this list. Future editions of the report were printed with a cover letter identifying this mistake, and a letter of apology was sent to Farm Sanctuary.[46]

See also

- Factory farming

- Animal welfare

- Animal rights

- The Humane Society of the United States

- List of animal rights groups

People

References

- ^ "New York Shelter". Farm Sanctuary. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Southern California Shelter". Farm Sanctuary. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Hall Of Fame". Animal Rights National Conference. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ^ Sweet, Joni (September 14, 2011). "Farm Sanctuary Grows". VegNews. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012.

- ^ McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (January 2, 2004). "Where the Cows Come Home; Sanctuary Farm Applauds Ban on Butchering of Sick Animals". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Severson, Kim (July 25, 2007). "Bringing Moos and Oinks Into the Food Debate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Hilda: The First Animal Rescued by Farm Sanctuary". Farm Sanctuary. September 25, 2000. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Baur, Gene (2008). Farm Sanctuary: Changing Hearts and Minds About Animals and Food. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743291590. LCCN 2008297873.

- ^ Voerding, Brian (June 6, 2008). "Farm Sanctuary founder in town to talk vegan". MinnPost. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011.

- ^ Baur, Gene; Stone, Gene (2015). Living the Farm Sanctuary Life: The Ultimate Guide to Eating Mindfully, Living Longer, and Feeling Better Every Day. Rodale Books. ISBN 978-1623364892. LCCN 2015008598.

- ^ "This Week's Bestsellers: April 20, 2015". Publishers Weekly. April 17, 2015. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020.

- ^ Crawford, Amanda J. (October 28, 2006). "Hog industry realities color Prop. 204 debate". The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011 – via the University of Arizona.

- ^ Lovley, Erika (November 10, 2006). "Pigs Win Bigger Pens in Arizona Ballot Fight". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020.

- ^ Rojas, Aurelio (September 27, 2008). "2008 Ballot Watch: Proposition 2: Standards for confining farm animals". The Sacramento Bee. p. A3.

- ^ Schmit, Julie (November 3, 2008). "Agribusiness fights California proposal that expands animal rights". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019.

- ^ "Election Results 2008 – California". The New York Times. December 9, 2008. Archived from the original on August 9, 2019.

- ^ Milionis, Allison (January 20, 2005). "Protests target Wolfgang Puck's Spago in effort to reform farm animal conditions". LA CityBeat.

- ^ Paulson, Amanda (December 13, 2005). "A ban on foie gras? Could this really be Chicago?". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Chicago servers and stores ignore foie gras ban". CBC News. January 10, 2007. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (May 15, 2008). "City repeals foie gras ban". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Cohen, Aleriella (February 17, 2007). "Fowl play: Fairway ducks foie gras flap". The Brooklyn Paper. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020.

- ^ Mooney, Jake (March 4, 2007). "Praise for Foie Gras Fortifies Its Critics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015.

- ^ "Westside Market Takes Stand Against Animal Cruelty, Signs Farm Sanctuary's "No Foie Gras" Pledge" (Press release). Farm Sanctuary. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ^ Dave, Shruti (January 12, 2007). "Craving foie gras? Look beyond Stephen Starr". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Archived from the original on July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Animal Clones Approved for Human Food". Environmental News Service. January 15, 2008. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ Hamblett, Mark (December 30, 2003). "Challenge to U.S. Meat Inspections Moves Forward". New York Law Journal. Archived from the original on January 3, 2004.

- ^ United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, Baur v. Veneman, AltLaw, December 16, 2003

- ^ Baur, Gene (2008). Farm Sanctuary: Changing Hearts and Minds About Animals and Food. Simon & Schuster. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0743291590. LCCN 2008297873.

- ^ Yoder, Michael (March 19, 2009). "It started at the stockyards: Banning downed cattle". Intelligencer Journal. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012.

- ^ New Jersey Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, et al. v. New Jersey Department of Agriculture, et al. (A-27-07)Rutgers School of Law, Camden, Law Library Archived July 17, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Burger King Says No to Soy Patties in Berkeley". The New York Times. May 15, 1994. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018.

- ^ Zunitch, Victoria (May 14, 2002). "Burger King serves up veggie burger". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016.

- ^ Krummert, Bob (March 30, 2007). "Going All-Natural One Better". Restaurant Hospitality. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020.

- ^ "A Not So Bizarro Trio Announces Partnership: Turtle Mountain, Farm Sanctuary & Syndicated Cartoonist Dan Piraro" (PDF) (Press release). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ Short, Alice (September 9, 2008). "Pigging out at Farm Sanctuary". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012.

- ^ 2008 Midwest Flood Pig Rescue

- ^ "Coston '87 Enjoys Labor of Love on the Farm", West Virginia Wesleyan College Campus News, August 2, 2007

- ^ Sachs, Andrea (June 15, 2008). "I Love Moo: Tales From A N.Y. Animal Sanctuary". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015.

- ^ Longley, Rick (February 15, 2008). "Farm Sanctuary Provides Haven". Orland Press-Register.

- ^ Severson, Kim (November 22, 2007). "In Some Households, Every Day Is Turkey Day". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018.

- ^ Sanctuary Tails

- ^ Rodriguez, Leila (April 23, 2018). "More room to roam: Orland Farm Sanctuary bids farewell". Chico Enterprise-Record. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Farm Sanctuary Adds Animal Acres' Southern California Shelter to Its National Program" (Press release). Animal Acres. September 14, 2011. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011.

- ^ Greenwood, Arin (October 26, 2015). "Jon Stewart Makes His Post-'Daily Show' Plans Official". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015.

- ^ United States Department of Justice, Report to Congress on the Extent and Effects of Domestic and International Terrorism on Animal Enterprises, Appendix 1

- ^ Anthony, Sheila F. (November 10, 1993). "DOJ Letter" (PDF). Office of Legislative Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2008 – via Farm Sanctuary.

External links

- Official website

- Gene Baur talks about his book "Farm Sanctuary" in mp3 recorded July 25, 2008 in Sacramento, California

- A Haven From the Animal Holocaust. Chris Hedges, August 2, 2015.