Electronic evidence

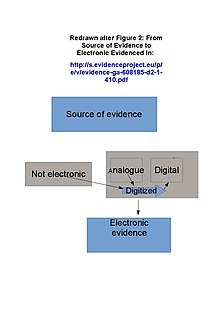

Electronic evidence consists of these two sub-forms:

- analog (no longer so prevalent, but still existent in some sound recordings e.g), and

- digital evidence (see longer article)

This rather complex relationship can be depicted graphically as shown in this part of an EU-funded project on the topic embedded here at the right. Chapter 10 of the associated 2018 book goes into more detail,[1] as does the website, http://www.evidenceproject.eu/categorization

Electronic evidence can be abbreviated as e-evidence; this shorter term is gaining in acceptance in Continental Europe. This page covers mainly activity there and on the international level.[2]

Access to electronic evidence

Access is the area where much of the current activity on the international level is taking place. A network called the Internet & Jurisdiction Policy Network holds global conferences on the topic at various locations.[3] Here are six key supranational developments in Geneva, New York, Strasbourg, Paris and Brussels. In February 2022 an authoritative report was published covering worldwide developments.[4]

Global Privacy Assembly

The GPA of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners "unsurprisingly places greater emphasis on individuals’ privacy rights than did the OECD draft" of 2021.[5] In 2021 GPA developed a document summing up its concerns. [6]

There is an international forensic standard issued by ISO with the International Electrical Commission ISO/IEC 27037.[7]

Late in 2019 Russia and China initiated a move to consider drafting a global cybercrime convention. Western democracies are conspicuously absent from the sponsoring parties.[8] Many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have issued a protest letter claiming the Russian initiative would potentially infringe upon human rights.[9] The General Assembly, to the surprise of many observers, approved both the proposals of the United States and Russia. [10]

Council of Europe

The Convention on Cybercrime (“Budapest Convention”) is "the first international treaty on crimes committed via the Internet".[11]

The CoE is currently drafting an update in the form of a second additional protocol to the Convention. An international group of national data protection authorities with a secretariat in Germany called the International Working Group on Data Protection in Telecommunications is monitoring the Council of Europe Cybercrime Convention holding 60-some meetings on the access problem, most recently to address events in Brazil, Belgium and China in addition to the Microsoft Ireland case.[12]

The draft protocol has proven quite controversial.[13] Two joint civil society statements have been submitted.[14] [15] "The Cybercrime Convention Committee had extended the negotiations of the protocol to December 2020." [16] Meanwhile there are the guidelines from 2019. [17]

OECD

In 2021 deliberations began at the OECD to develop common principles among member countries. There are two major methods of access: compelled (or obliged) access and direct (including covert) access. The EU wants to address both, whereas the United States is hesitant to include covert access. [18]

European Union

The European Commission (as the only body holding the right of initiative) has made two legislative proposals (a Directive on establishing a legal representative,[19] and a Regulation on access to evidence for criminal investigations).[20] Taken together, these proposals comprise a "package". The legislators, i.e. the Parliament and the Council, have meanwhile found positions in regard to that Commission proposal. The Council calls its position a "general approach".

The committees in the Parliament have different competences, which are sometimes not easily distinguished, so sometimes there are competence disputes. LIBE has received "the lead", or lead competence working on the proposals, and has subsequently produced a report. The rapporteur Birgit Sippel MEP proposed changes to the versions of the Commission and the Council. The report has given rise to both a summary [21] and a more detailed commentary analysing its provisions for their efficiency and protection of human rights.[22] Agreement has been reached in the Parliament on how to enter the trilogue negotiations (EP+CoU+COM). [23] The differences in the two versions prepared by the Council and Parliament respectively are shown in a couple of documents [24]

In what can be seen as an accelerated procedure as opposed to the ordinary first reading/second reading procedure, the report was only voted on in LIBE. The EP Plenary then mandated the committee to take up negotiations with the Council, while the Commission formally played a neutral advisory role. Formally, the first reading will not be closed until the trilogue has reached an agreement. Then the plenary will vote on the trilogue negotiation outcome as its first reading position, and effectively also allow it to become law. There could also be a situation where no agreement can be reached, in which case the Parliament would vote on the unchanged LIBE report to finalise the first reading and make it the Parliament position, before entering into a second reading. In July 2022 there has been movement in the negotiations. [25]

Authoritative texts can be found on the eur-lex website. [26]

In February 2019, the European Commission recommended "engaging in two international negotiations on cross-border rules to obtain electronic evidence," one involving the USA [27] and one at the CoE.[28] Indeed, the USA/EU axis and the CoE are the scenes of work on these issues, as described and compared in a 2019 paper advocating a revamping of the Mutual legal assistance treaty, page 17.[29]

The reason for the above development was given as due to the fact that "[i]n the offline world, authorities can request and obtain documents necessary to investigate a crime within their own country, but electronic evidence is stored online by service providers often based in a different country than [sic] the investigator, even if the crime is only in one country." The Commission then gave data supporting this decision.[30] Indeed, this is the reason for treating electronic evidence differently from the ways that other evidence is treated. Moreover, it may expedite convergence or some form of reconciliation between the world's two main legal systems, i.e. common law and civil law, at least as regards this use case. Negotiations are set to begin.[31] However, there are questions as to how the two different systems might converge in a common agreement. [32] A deadlock may exist in Europe. [33]

The core instruments to handle cross-border requests are: a European Production Order (EPOC) and a European Preservation Order (EPOC-PR). The framework for those instruments is the European evidence warrant.[34]

Separately from the above, a dedicated convention has been drafted by a British barrister.[35]

United Kingdom

The UK government announced that the new "UK-US Bilateral Data Access Agreement will dramatically speed up investigations and prosecutions by enabling law enforcement, with appropriate authorisation, to go directly to the tech companies to access data, rather than through governments, which can take years."

"It gives effect to the Crime (Overseas Production Orders) Act 2019, which received Royal Assent in February this year and was facilitated by the CLOUD Act in America, passed last year."

"The Agreement does not change anything about the way companies can use encryption and does not stop companies from encrypting data." On encryption, the US, UK and Australia are contacting Facebook directly [36]

The agreement means that UK officials can now apply to the US via the Crime (Overseas Production Orders) Act 2019.[37]

United States

The basis for obtaining cross-border access is the Stored Communications Act as amended by the CLOUD Act. A new agreement with the UK was negotiated and it "will enter into force following a six-month Congressional review period mandated by the CLOUD Act, and the related review by UK’s Parliament."[38]

Controversy

One of the most controversial cases brought yet to a court has been the 2013 Microsoft Corp. v. United States case.

Potential conflicts between the EU regime and the US CLOUD Act have led legal scholars Jennifer Daskal and Peter Swire to propose a US/EU agreement.[39] Those authors have also assembled a set of FAQ seeking to address questions specifically that have arisen from the European Union in connection with the CLOUD Act.[40]

Highlighting differences from the status quo, the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs commissioned a study and held a hearing; the study is available.[41]

Europeans discussing ‘Co-operating in the Digital Age’ in the Internet Governance Forum have been critical of the EU's proposals, fearing that "companies and businesses [might] implement stronger filtering and blocking mechanisms in order to avoid sanctions or reputational damages."[42] Later in November at the Internet Governance Forum 2019 in Berlin panelists described new initiatives in Brazil and Russia respectively. [43]

Some problems quite different from those in the Microsoft case alluded to above have been found and described in an article in the German weekly ZEIT dated 19 December 2018 with 167 comments on the proposed direct access tracks described above under "European Union"; the journalist Martin Klingst entitled it "Nackt per Gesetz" (Naked by Law, meaning exposed to foreign observation by domestic law).[44]

Klingst is appalled at the thought that an EU member state like Hungary might demand his data. Apparently Katharina Barley, German Federal Minister of Justice, agrees. Germany has protections against infringements on one's "informational self-determination" that are the strongest of any EU member state. The European Arrest Warrant is another example of the national limits placed on EU rights in some conditions.

Besides, Klingst sees a contradiction between having Internet companies be the guardians of right and wrong, whereas in a new draft German law they might be punished themselves. Would other MSs respect Germany's interpretation of who maintains confidentiality? he asks rhetorically.

E-evidence could become the first case, Klingst predicts, testing whether Germany's top judges have reserved enough room for the most basic protections.

Much evidence is plain text; but some evidence is encrypted. In 2015 and 2016, another chapter was added to the long-standing encryption controversy with the FBI-Apple encryption dispute. That controversy continues in 2019 with multiple nation-states pressuring Facebook to put a backdoor in its messenger service.[45]

References

- ^ Handling and Exchanging Electronic Evidence Across Europe. Maria Angela Biasiotti, Jeanne Pia Mifsud Bonnici, Joe Cannataci, Fabrizio Turchi (editors)

- ^ "Evidence" itself is a contested term. Before being accepted in a court of law, the thing under question is merely "information" or "data," at best potential evidence. Carrera, Sergio; Stefan, Marco; Mitsilegas, Valsamis. "Cross-border data access in criminal proceedings and the future of digital justice, Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), Brussels, October 2020" (PDF). Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ especially its Data and Jurisdiction Work Plan on pp. 6 ff. of its 2018 Ottawa Roadmap "Towards Policy Coherence and Joint Action. Summary by the Secretariat of the Internet and Jurisdiction Policy Network and Ottawa Roadmap" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ United Nations Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate (CTED). "The state of international cooperation for lawful access to digital evidence, Jan. 2022" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Christakis, Theodore; Propp, Kenneth; Swire, Peter (20 December 2021). "Towards OECD Principles for Government Access to Data: Can Democracies Show the Way?". Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Adopted resolution on Government Access to Data, Privacy and the Rule of Law: Principles for Governmental Access to Personal Data held by the Private Sector for National Security and Public Safety Purposes, 43rd Closed Session of the Global Privacy Assembly, October 2021" (PDF). Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Forensics Standards (ISO/IEC 27037 ISO/IEC 27037:2012 information technology -- Security techniques -- Guidelines for identification, collection, acquisition and preservation of digital evidence". Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly. "Seventy-fourth session, Third Committee, Agenda item 107, Countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes". Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ 38 NGOs under the leadership of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC). "Open letter to UN General Assembly: Proposed international convention on cybercrime poses a threat to human rights online". Retrieved 1 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Alex Grigsby. "The United Nations Doubles Its Workload on Cyber Norms, and Not Everyone Is Pleased". Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Council of Europe. "Details of Treaty No.185, Convention on Cybercrime". Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ "Working paper on Standards for data protection and personal privacy in cross-border data requests for criminal law enforcement purposes 63rd meeting, 9-10 April 2018, Budapest (Hungary)" (PDF). Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Rodriguez, Katitza (2019-02-21). "What's the Emergency? Keeping International Requests for Law Enforcement Access Secure and Safe for Internet Users, Electronic Freedom Foundation". Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ "Joint Civil Society Response to the provisional draft text of the Second Additional Protocol to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime" (PDF). Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), European Digital Rights (EDRi), IT-Pol Denmark, Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC). Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ "Privacy & Human Rights in Cross-Border Law Enforcement, Ver 2, Electronic Freedom Foundation, European Digital Rights (EDRi), IT-Pol Denmark, Fundacion Karisma" (PDF). August 9, 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Daskal, Jennifer; Kennedy-Mayo, DeBrae (2 July 2020). "Budapest Convention: What is it and How is it Being Updated? July 2, 2020". Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Council of Europe. "Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on electronic evidence in civil and administrative proceedings, January 2019". Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Christakis, Theodore; Propp, Kenneth; Swire, Peter (20 December 2021). "Towards OECD Principles for Government Access to Data: Can Democracies Show the Way?". Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ See Parliament's document repository for the Directive: "2018/0107(COD) Appointment of legal representatives for the purpose of gathering evidence in criminal proceedings". Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ See Parliament's document repository for the Regulation: "2018/0108(COD) European production and preservation orders for electronic evidence in criminal matters".

- ^ Christakis, Théodore (21 January 2020). "E-Evidence in the EU Parliament: Basic Features of Birgit Sippel's Draft Report". European Law Blog. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Christakis, Théodore (7 January 2020). "Lost in Notification? Protective Logic as Compared to Efficiency in the European Parliament's E-Evidence Draft Report". Cross-Border Data Forum. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "MEPs want legally sound solutions for obtaining e-evidence in cross border cases, Press Release". European Parliament. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "EU: Secret negotiations on e-evidence: Council and Parliament positions side-by-side". Statewatch. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "E-evidence will bring a major paradigm shift in police, justice and service provider cooperation in the EU, Press Release". Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists & Democrats in the European Parliament. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "EU law - EUR-Lex".

- ^ Christakis, Theodore (2019-01-14). "E-Evidence in a Nutshell: Developments in 2018, Relations with the Cloud Act and the Bumpy Road Ahead". Cross-Border Data Forum. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ European Commission. "European Commission - Press release. Security Union: Commission recommends negotiating international rules for obtaining electronic evidence, Brussels, 5 February 2019". Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Hohmann, Mirko; Barnett, Sophie. "System Upgrade: Improving Cross-Border Access to Electronic Evidence, Global Public Policy Institute, January 2019" (PDF). Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ European Commission. "European Commission - Fact Sheet Questions and Answers: Mandate for the EU-U.S. cooperation on electronic evidence". Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ European Commission. "Criminal justice: Joint statement on the launch of EU-U.S. negotiations to facilitate access to electronic evidence, Washington, DC, 26 September 2019". Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ Christakis, Theodore; Terpan, Fabien (12 February 2021). "EU-US Negotiations on Law Enforcement Access to Data: Divergences, Challenges and EU Law Procedures and Options, Open Access". International Data Privacy Law. 11 (2). Oxford University Press: 81–106. doi:10.1093/idpl/ipaa022. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Propp, Kenneth (2 June 2022). "Has the Time for an EU-U.S. Agreement on E-Evidence Come and Gone? Open Access". Lawfare blogs. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Williams, Charles (2006). "The European evidence warrant". Revue Internationale de Droit Pénal. 77 (1): 155–162. doi:10.3917/ridp.771.0155. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Electronic Evidence, Draft Convention on (2016). "Draft Convention on Electronic Evidence". Digital Evidence and Electronic Signature Law Review. 13. doi:10.14296/deeslr.v13i0.2321.

- ^ "UK and US sign landmark Data Access Agreement, October 3, 2019". UK Government, Crime, justice and law. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ The Act is here, and Explanatory Notes to the Act are available from a tab. "Crime (Overseas Production Orders) Act 2019, 3 October 2019". UK Government, Legislation. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "U.S. And UK Sign Landmark Cross-Border Data Access Agreement to Combat Criminals and Terrorists Online, October 3, 2019". Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 3 October 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Daskal, Jennifer; Swire, Peter (21 May 2018). "A Possible US-EU Agreement on Law Enforcement Access to Data? May 21, 2018 [also cross-posted on Lawfare]". Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Swire, Peter; Daskal, Jennifer (April 16, 2019). "Frequently Asked Questions about the U.S. CLOUD Act". Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Boese, Martin. "An assessment of the Commission's proposals on electronic evidence, research paper requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs and commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizen's Rights and Constitutional Affairs". Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Amon, Cedric. "EuroDIG 2019: Highlights from The Hague, 2019". Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Maciel, Marilla. "Solutions for Law Enforcement to Access Data Across Borders, Report, Internet Governance Forum, Berlin, Workshop 288 (26 Nov 2019, 11:30 to 13:00)". Diplo Foundation. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Klingst, Martin (19 December 2018). "Nackt per Gesetz" (Naked by Law)".

- ^ "US, UK and Australia urge Facebook to create backdoor access to encrypted messages". The Guardian. 3 October 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

Further reading

Journals

- Digital Evidence and Electronic Signature Law Review (open access), http://journals.sas.ac.uk/deeslr/

- Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law (open access), https://commons.erau.edu/jdfsl/

Books

- Paul, George L.: Foundations of Digital Evidence (American Bar Association, 2008)

- Scanlan, Daniel M.: Digital Evidence in Criminal Law (Thomson Reuters Canada Limited, 2011)

- Scheindlin Shira A. and The Sedona Conference (2016): Electronic Discovery and Digital Evidence in a Nutshell, Second Edition, West Academic Publishing, ISBN 978 1 63459 748 7