East York Militia

| East Riding Trained Bands East York Militia 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Battalion |

| Part of | East Yorkshire Regiment |

| Garrison/HQ | Victoria Barracks, Beverley |

| Nickname(s) | 'Beverley Buffs' 'Yorkshire Buffs' |

| Battle honours | South Arica 1902 |

The East York Militia was a part time home defence force in the East Riding of Yorkshire. The Militia and its predecessors had always been important in Yorkshire, and from its formal creation in 1759 the regiment served in home defence in all Britain's major wars until 1919. It became a battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment, and its role during World War I was to train thousands of reinforcements for the regiment's battalions serving overseas.

Early history

The English Militia was descended from the Anglo-Saxon Fyrd, the military force raised from the able-bodied freemen of the shires under command of their Sheriffs. The three Ridings of Yorkshire and adjacent counties provided the bulk of the fyrdmen who fought against Harald Hardrada at the Battles of Fulford and Stamford Bridge in 1066.[1][2] The Shire levy continued under the Norman and Plantagenet kings: Yorkshire levies helped to defeat the Scots army at the Battle of the Standard (1138). The Shire levy was reorganised under the Assizes of Arms of 1181 and 1252, and again by the Statute of Winchester of 1285.[3][4][5] East Riding levies were regularly employed in offensive and defensive campaigns against Scotland, including the battles of Halidon Hill (1333), Neville's Cross (1346), Berwick (1482) and Flodden (1513). They were also seen in domestic conflicts such as the Wars of the Roses: the Mayor of Kingston upon Hull (Hull) was killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1461 at the head of three companies of infantry raised in the town, and East Riding detachments were prominent in the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536.[1]

East Riding Trained Bands

Under the Tudors the legal basis of the militia was updated by two acts of 1557 covering musters (4 & 5 Ph. & M. c. 3) and the maintenance of horses and armour (4 & 5 Ph. & M. c. 2), which placed the county militia under a Lord Lieutenant appointed by the monarch, assisted by the Deputy Lieutenants and Justices of the Peace. The entry into force of these Acts in 1558 is seen as the starting date for the organised county militia in England. Although the militia obligation was universal, it was clearly impractical to train and equip every able-bodied man, so after 1572 the practice was to select a proportion of men for the Trained Bands, who were mustered for regular drills.[6][7][8][9][10][11] During the Armada campaign of 1588, the militia of Yorkshire were assigned to watch Scotland and the East Coast of England.[12] The East Riding Trained Bands mustered 1600 men, of whom 640 were armed with calivers, 560 with pikes, 240 with bills and 160 with bows.[11]

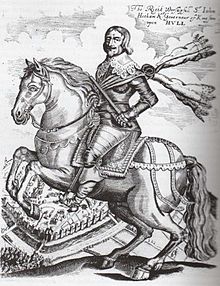

Charles I attempted to bolster the Trained Bands as a national force under royal control. In the Bishops' Wars the East and North Yorkshire Trained Bands were expected to join the King's Army, with deficiencies in their arms made up from the arsenal at Hull, but there was great reluctance throughout the militia to serve outside their own counties, even for pay.[13] Control of the militia was one of the areas of dispute between King Charles I and Parliament that led to the First English Civil War. On 12 February 1641 Parliament appointed the Earl of Essex as a fit person to be entrusted with organising the Trained Bands of Hull and the East Riding.[14] When Charles approached Hull in April 1642, Parliament's governor, Sir John Hotham, called out 800 men of the Trained Bands (illegally, since the position of Lord Lieutenant was vacant) and prevented the king from seizing the arsenal. In response, Charles called out the remainder of the East Riding's men as a regiment under Sir Robert Strickland to join his investing army. In the event, both sides took the Trained Bands' weapons and gave them to paid volunteers who would serve anywhere in the kingdom in permanent regiments.[15][16]

On the Restoration of the Stuarts the Militia was reorganised (though the term 'Trained Band' endured in East Yorkshire until the end of the 17th century). In 1689 the East Riding's contingent consisted of one regiment of foot commanded by the Marquis of Carmarthen as Lord Lieutenant, made up of eight companies with a total strength of 679, and two 64-man Troops of cavalry.[17] In the 1697 returns, the East Riding had one regiment of eight companies of foot totalling 679 men, and two troops of horse with 128 men, under Colonel the Marquis of Carmarthen (son of the Lord Lieutenant, who had been elevated to Duke of Leeds). When mustered they 'appeared to be in very good order'.[14] At the time of the Jacobite rising of 1715 the East Riding Regiment of Militia consisted of about 670 men under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Hildyard. Thereafter the militia was allowed to decline, although when Viscount Irwin became Lord Lieutenant of the East Riding in 1738 he reviewed the state of the militia and began to appoint new officers. Nevertheless when the Jacobite rising of 1745 began he advised against calling out the inefficient militia and instead enrolled volunteer companies for home defence.[17]

East York Militia

Under threat of French invasion during the Seven Years' War a series of Militia Acts from 1757 re-established county militia regiments, the men being conscripted by means of parish ballots (paid substitutes were permitted) to serve for three years. There was a property qualification for officers, who were commissioned by the Lord Lieutenant. Opposition to the ballot led to rioting in some counties, including the East Riding, and organisation of the new force proceeded slowly. In the East Riding the first issue of arms was only made on 3 December 1759; the regiment was embodied at Beverley for service on 8 January 1760 and marched off to Newcastle upon Tyne. The East York Regiment of Militia comprised 33 officers and 460 other ranks, organised into 10 companies, under the command of Colonel Sir Digby Legard, 5th Baronet. The men were known locally as the 'Beverley Buffs' or the 'Yorkshire Buffs' from the colour of their uniform's facings.[14][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

The militia was stood down ('disembodied') at the end of the war, after which their obligation was for 28 days' training each year, but this was often neglected. The East York Militia was embodied again on 3 March 1778 during the War of American Independence when Britain was threatened with invasion by the Americans' allies, France and Spain. The East York Regiment, commanded by Henry Maister, was complimented on its appearance and drill when it was inspected at York before marching south.[20][22][26][27][28] The East York Militia was at Warley Camp in Essex in the summer of 1778 and the following summer at Coxheath Camp near Maidstone in Kent. At these large training camps the Militia were exercised as part of a division alongside Regular troops while providing a reserve in case of French invasion of South East England.The East Yorks along with the North Yorks Militia formed part of the Left Wing at Coxheath. Each battalion had two small field-pieces or 'battalion guns' attached to it, manned by men of the regiment instructed by a Royal Artillery sergeant and two gunners.[25][29][30] The regiment was disembodied in March 1783.[25][22]

Militia training was again neglected during the subsequent peace,[31] but the regiments were embodied for almost continuous service during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars of 1793–1815. On 28 December 1792 the East York Militia was reviewed by the Lord Lieutenant in Beverley Minster (its normal place for parades in the winter) and on 31 December the regiment was embodied, still under Henry Maister (who would remain in command until 1803). In February 1793 the regiment marched to King's Lynn where it was employed in coast defence. Under the Militia Act 1794 a further two companies were raised for the regiment in 1795.[19][25][32][33]

In July 1796 the regiment was part of a militia encampment at Brighton under Maj-Gen Jones.[34] In 1797 the regiment formed part of the force stationed at Sheerness at the time of the Royal Navy Mutiny at the Nore. Sergeant Sutherland with a small detachment repelled a party of mutinous seamen and marines who attempted to land at Minster-in-Sheppey. For this action Sgt Sutherland was granted an Ensign's commission.[14]

During the French Wars the militia were employed anywhere in the country for home defence, manning garrisons, guarding prisoners of war, and for internal security, while the Regular Army regarded them as a source of trained men if they could be persuaded to transfer. Their traditional local defence duties were taken over by the Volunteers. As the invasion threat grew in 1796 the Militia was doubled in size: the East Riding was given an additional quota of 861 men to raise for the East York Supplementary Militia. The supplementary militia was disembodied in October 1799, but a fresh invasion scare in August 1801 led to them being re-embodied. The East York Supplementary Militia were sent to reinforce the main regiment, which at the time was deployed along the coast at Whitby, Scarborough and Bridlington; they were incorporated into the 'Old' East York Militia on 7 September. However, the preliminaries of the Treaty of Amiens were signed in October, and the militia regiments were marched back to their counties to be disembodied.[23][25][33][35][20][36]

The Peace of Amiens quickly broke down, and the militia were called out once more, the East Yorks regiment being embodied on 21 March 1803 under the command of Col Sir Charles Hotham, commissioned on 16 May. However, he was court-martialled on charges of irregularity and drunkenness of duty, and was succeeded by Col Arthur Maister, commissioned on 12 February 1808.[25] After embodiment the regiment was marched to Chelmsford to resume home defence duties, while new volunteer units were formed.[37][38] During the critical invasion summer of 1805, when Napoleon was massing his 'Army of England' at Boulogne for a projected invasion, the East York Militia was stationed at Dover Castle and Dover Western Heights. On 1 September 1805, with 595 men in eight companies under the command of Lt-Col Maister, it was in Dover Barracks as part of Maj-Gen Lord Forbes's militia brigade.[39][40] In 1810 the East York Militia was sent to London to suppress anticipated riots, and was stationed at the Royal Mint on Tower Hill.[14]

In 1807 the volunteer units were virtually abolished and replaced by a new force of Local Militia. These regiments were intended to serve only in their own counties and to be embodied only for short training periods, even in time of war. No substitutes were accepted, and men previously exempt from the Militia Ballot were liable for call-up; service was for four years. Most of the officers came from the old volunteer units. The East Riding organised four battalions of Local Militia:[38][41][42]

- 1st Battalion at Pocklington, 800 men commanded by Lt-Col Robert Dennison

- 2nd Battalion at Bridlington, 800 men commanded by Sir Mark Masterman-Sykes, MP

- 3rd Battalion at Beverley, 800 men commanded by Lt-Col Richard Bethell

- 4th Battalion at Hull, 1000 men commanded by Lt-Col John Wray

The Local Militia mustered for 28 days' training each year from 1808 until the end of the war. They ceased training in 1816, and were abolished in 1836.

The East York Militia was disembodied in 1814 but called out again in June 1815 when Napoleon escaped from Elba, and was finally disembodied in 1816.[25] After the Battle of Waterloo the Militia declined once more: the East York Militia was only mustered for annual training on four occasions between 1817 and 1851 (1820, 1821, 1825 and 1831), though officers were still commissioned into the unit. Lieutenant-Colonel George Hamilton Thompson, former Lieutenant in the 1st King's Dragoon Guards, commanded the regiment from 15 November 1833 until he was appointed Honorary Colonel on 10 May 1871.[43][44][45]

The Militia of the United Kingdom was reformed by the Militia Act 1852, enacted during a period of international tension. As before, units were raised and administered on a county basis, and filled by voluntary enlistment (although conscription by means of the Militia Ballot might be used if the counties failed to meet their quotas). Training was for 56 days on enlistment, then for 21–28 days per year, during which the men received full army pay. Under the Act, Militia units could be embodied by Royal Proclamation for full-time home defence service in three circumstances:[43][46][47][48][49]

- 1. 'Whenever a state of war exists between Her Majesty and any foreign power'.

- 2. 'In all cases of invasion or upon imminent danger thereof'.

- 3. 'In all cases of rebellion or insurrection'.

The 1852 Act introduced Artillery Militia units in addition to the traditional infantry regiments. Their role was to man coastal defences and fortifications, relieving the Royal Artillery for active service.[46][47] In June 1860 the East York Artillery Militia appeared in the Army List, but no officers were appointed to it, and in December 1860 it was announced that it would be joined with the North Riding unit that was also being formed. The East and North York Artillery Militia appeared in the Army List from January 1861; one captain and 257 volunteers were transferred to the new unit from the East York Militia.[43][50][51]

During the Crimean War the East York Militia was embodied from 4 February 1855 to June 1856.[19][14][43] However, once peace returned only 250 out of the 900 men due to turn out for annual training in 1859 actually appeared, and there was a shortage of young officers. This was a year in which there was a new invasion scare, which saw the emergence of a new Volunteer Force. The Volunteers usurped much of the Militia's public support, as well as part of its role in home defence.[43][52]

the Militia Reserve introduced in 1867 consisted of present and former militiamen who undertook to serve overseas in case of war.[53][54][55]

3rd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment

Under the 'Localisation of the Forces' scheme introduced by the Cardwell Reforms of 1872, Militia regiments were grouped into county brigades with their local Regular and Volunteer battalions – for the East York Militia this was with the 15th Foot in Brigade No 6 (East Riding of Yorkshire) in Northern District. A second militia battalion was supposed to have been formed in this brigade, but this never happened. The Militia were now under the War Office rather than their county Lord Lieutenant.[45][56][57] Following the Cardwell Reforms a mobilisation scheme began to appear in the Army List from December 1875. This assigned Regular and Militia units to places in an order of battle of corps, divisions and brigades for the 'Active Army', even though these formations were entirely theoretical, with no staff or services assigned. The East York Militia was assigned to 1st Brigade of 3rd Division, VIII Corps in Scotland. The brigade would have mustered at Melrose in time of war.[45][58]

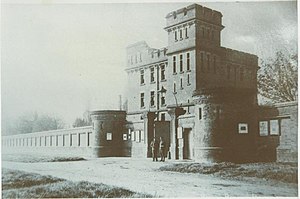

The Childers Reforms of 1881 took Cardwell's reforms further, with the militia formally joining their linked regiments as their 3rd Battalions. The 15th Foot became the East Yorkshire Regiment and the East York Militia became 3rd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, with its cadre of permanent staff sharing the regimental depot built at Victoria Barracks, Beverley, in 1877.[19][14][45][59]

The 3rd Battalion was embodied during the Second Boer War, first from 4 May to 4 December 1900, when it served at home. By then 192 men of the Militia Reserve were serving with the line battalions of the East Yorkshires. The 3rd Battalion then volunteered for service again and was embodied on 17 February 1902. It embarked for South Africa under Lt-Col H. Walker and was largely employed guarding the bridge over the Orange River and section of the railway line near Bethulie. It was disembodied 10 October 1902. The battalion received the Battle Honour South Africa 1902 and the officers and men received the Queen's South Africa Medal with the clasps for 'Cape Colony, 'Orange Free State', and 'South Africa 1902'.[19][14][45]

Special Reserve

After the Boer War, there were moves to reform the Auxiliary Forces (Militia, Yeomanry and Volunteers) to take their place in the six Army Corps proposed by St John Brodrick as Secretary of State for War. However, little of Brodrick's scheme was carried out.[60][61] Under the more sweeping Haldane Reforms in 1908, the Militia was replaced by the Special Reserve, a semi-professional force whose role was to provide reinforcement drafts for Regular units serving overseas in wartime.[62][63] The East York Militia became 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment

World War I

3rd (Reserve) Battalion

On the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914 the battalion was mobilised at Beverley under the command of Lt-Col Francis Strickland-Constable and moved to its war station at Hedon, near Hull, where the men went into billets and battalion headquarters was established at Holyrood House. Intensive training of reservists and recruits began, with musketry courses fired at Hornsea. From Hedon the battalion despatched its first reinforcement draft (one officer and 95 other ranks) on 25 September to the 1st Battalion fighting on the Aisne, and sent five further drafts in October and November.[19][64][65][66] In December the 2nd Battalion returned from service in India and it also went to France in January 1915.[67] The 3rd Battalion began to supply drafts to this battalion as well. As the prewar reservists and special reservists were used up, the drafts were increasingly made up of wartime recruits and returning wounded. In November 1914 the 3rd Battalion used its surplus manpower to form 9th (Reserve) Battalion (see below) to carry out the same role for the 'Kitchener's Army' battalions of the regiment, but by January 1915 the battalion still numbered more than 2000 all ranks[68][69]

On 6 June 1915, Hull was bombed by a German Zeppelin, and there was an outbreak of violence against shops in the city bearing German names. 3rd Battalion was called upon to furnish strong picquets to assist the police in restoring order. The battalion also held a recruiting parade through the city on 9 September.[68][70]

At the end of 1915 the recruit companies moved to South Dalton camp by a route march, and in January two new companies to were formed to meet the influx of men enlisted under the Derby Scheme. These companies consisted of men enlisted for labour and home service only; the labourers were transferred to Bradford in February 1916 as No 1 Works Company, East Yorkshire Regiment. In April 1916 the battalion relinquished its billets and hired buildings in Hedon and moved to a hutted camp at Withernsea, while the recruit companies moved from South Dalton Camp to huts at Hedon. During the winter the battalion stationed a detachment at Pocklington. Lieutenant-Colonel Strickland-Constable handed over command to Lt-Col C. Etheridge (Warwickshire Regiment) on 23 June 1916. (Lt-Col Strickland-Constable died on service on 20 December 1917 and was buried in St Laurence Churchyard, Sigglesthorne.[71][72]) The battalion remained at Withernsea for the rest of the war as part of the Humber Garrison, training thousands of recruits.[64][65][68] The battalion was disembodied on 9 September 1919, with the remaining personnel transferred to the 1st Battalion.[19]

9th (Reserve) Battalion

After Lord Kitchener issued his call for volunteers in August 1914, the battalions of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd New Armies ('K1', 'K2' and 'K3' of 'Kitchener's Army') were quickly formed at the regimental depots. The SR battalions also swelled with new recruits and were soon well above their establishment strength. On 8 October 1914 each SR battalion was ordered to use the surplus to form a service battalion of the 4th New Army ('K4'). Accordingly, the 9th (Service) Bn was formed at York on 7 November from the surplus of the 3rd Battalion at Hedon. Under the command of Lt-Col H.A. Moore of the Indian Army it soon had 10 officers and 1100 other ranks. It trained to be part of 90th Brigade in 30th Division. On 10 April 1915 the War Office decided to convert the K4 battalions into 2nd Reserve units, providing drafts for the K1–K3 battalions in the same way that the SR was doing for the Regular battalions. The battalion became 9th (Reserve) Battalion in 2nd Reserve Brigade. At the end of May the battalion moved into camp outside Harrogate, where Col E.A.F. Carter of the 11th Bn Northumberland Fusiliers arrived to take command. In July the battalion despatched its first reinforcement draft (50 men to the 1st Bn East Yorks); thereafter it sent men principally to the 6th, 7th and 8th (Service) Bns, totalling 945 by the end of the year. On 1 September 1915 the battalion moved to Penkridge Bank Camp at Rugeley, Staffordshire. Between 1 January and 31 August 1916 it despatched another 840 reinforcements overseas. On 1 September 1916 the 2nd Reserve battalions were transferred to the Training Reserve and the battalion was redesignated 7th Training Reserve Bn, still in 2nd Reserve Bde at Rugeley. The training staff retained their East Yorks badges. On 1 December 1917 it became 49th Recruit Distribution Bn (dropping the 'Recruit' on 25 June 1918). It was disbanded at Ripon on 6 June 1919.[19][64][69][65][73][74][75]

Postwar

The SR resumed its old title of Militia in 1921 but like most militia battalions the 3rd East Yorkshires remained in abeyance after World War I (it only had one officer listed by 1939) until it was formally disbanded in April 1953.[19][45]

Uniform and insignia

The two Trained Band companies levied in Beverley were issued with grey coats in 1640.[11] The reorganised regiment in 1758 wore a scarlet coat with buff facings (from which it got the nickname 'Beverley Buffs'[19]) white waistcoats, scarlet breeches and white leggings. The Regimental Colour was buff, with the Union flag in the canton and the Coat of arms of the Lord Lieutenant (Henry, 7th Viscount Irwin) in the centre.[22] At Warley in 1779 the scarlet coat and buff facings were noted, and the grenadiers' black fur caps had a red back.[25][29] Apart from white breeches, the uniform colours were the same in 1792.[33] This uniform was also worn by the Supplementary Militia and, with minor alterations to badges, by the four battalions of Local Militia.[42][38]

In 1850 the officers of the disembodied East Yorkshire Militia wore the 1846 pattern uniform with buff facings and dark blue ('Oxford mixture') trousers with a narrow red welt. The headdress was an 'Albert' pattern Shako, the plate consisting of a gilt Garter star with a crown above and a scroll below carrying the words 'EAST YORK'; the shoulder belt plate bore a Rose of York with the same crown and scroll.[76] The regimental badge was listed in 1860 as being the 'White Rose of York'.[44] The regiment later adopted the white facings of the East Yorkshire Regiment.[45]

Honorary Colonels

The following served as Honorary Colonel of the unit:[14][45]

- George H. Thompson, former commanding officer, appointed 10 May 1871

- William H. Grimston, former commanding officer, appointed 1 November 1890

- Sir George Duncombe, 1st Baronet, former officer in the regiment, appointed 21 February 1903

Notes

- ^ a b Norfolk, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Stenton, pp. 588–91.

- ^ Fortescue, Vol I, p. 12.

- ^ Fissell, pp. 178–80.

- ^ Maitland, pp. 162, 276.

- ^ Beckett, Amateur Tradition, p. 20.

- ^ Boynton, Chapter II.

- ^ Cruickshank, pp. 17, 24–5.

- ^ Fortescue, Vol I, p. 125.

- ^ Maitland, pp. 234–5, 278.

- ^ a b c Norfolk, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Boynton, p. 159.

- ^ Fissell, pp. 195–214.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hay, pp. 284–5.

- ^ Norfolk, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Rogers, pp. 17–9.

- ^ a b Norfolk, pp. 5–9; Appendix I.

- ^ Fortescue, Vol II, pp. 288, 299, 301–2, 521.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Frederick, pp. 181–2.

- ^ a b c Holmes, pp. 94–100.

- ^ Norfolk, pp. 9–11.

- ^ a b c d Norfolk, Appendix II.

- ^ a b Western, Appendices A & B.

- ^ Western, p. 251.

- ^ a b c d e f g h East York Militia at School of Mars.

- ^ Fortescue, Vol III, pp. 173–4.

- ^ Norfolk, p. 11.

- ^ Maister family at Hullwebs.

- ^ a b W.Y. Carman, 'Philip J. de Loutherbourg and the camp at Warley, 1778', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 71, No 288 (Winter 1993), pp. 276–7.

- ^ Brigadier Charles Herbert, 'Coxheath Camp, 1778–1779', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 45, No 183 (Autumn 1967), pp. 129–48.

- ^ Fortescue, Vol III, pp. 530–1.

- ^ Norfolk, pp. 12–3.

- ^ a b c Norfolk, Appendix III.

- ^ Burgoyne, p. 23.

- ^ Norfolk, pp. 13–21.

- ^ Knight, pp. 78–9, 111, 238, 255, 411, 437–47.

- ^ Norfolk, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Norfolk, Appendix IV.

- ^ Brown.

- ^ H. Moyse-Bartlett, 'Dover at War', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 50, No 203 (Autumn 1972), pp. 131–51.

- ^ Norfolk, pp. 33–4.

- ^ a b East Yorkshire Local Militia at School of Mars.

- ^ a b c d e Norfolk, pp. 34–5.

- ^ a b Hart Army List, various dates.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Army List, various dates.

- ^ a b Litchfield, pp. 1–7.

- ^ a b Dunlop, pp. 42–5.

- ^ Grierson, pp. 12, 27–8.

- ^ Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 91–2.

- ^ Litchfield, pp. 145–6.

- ^ Norfolk, Appendix V.

- ^ Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 162–8.

- ^ Dunlop, pp. 42–52.

- ^ Grierson, 84–5, 113, 120.

- ^ Spiers, Late Victorian Army, pp. 97 102, 126–7.

- ^ Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 195–6.

- ^ Spiers, Late Victorian Army, pp. 4, 15, 19.

- ^ Spiers, Late Victorian Army, p. 59.

- ^ Grierson, pp. 33, 84–5, 113.

- ^ Dunlop, pp. 131–40, 158-62.

- ^ Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 243–2, 254.

- ^ Dunlop, pp. 270–2.

- ^ Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 275–7.

- ^ a b c James, p. 59.

- ^ a b c East Yorkshire Regiment at Long, Long Trail.

- ^ Wyrall pp. 19–20.

- ^ Wyrall, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Wyrall, pp. 397–8.

- ^ a b Wyrall, p. 402.

- ^ Bilton, pp. 81–6.

- ^ Burke, 'Strickland-Constable Baronets'.

- ^ CWGC record.

- ^ Becke, Pt 3b, Appendix I.

- ^ James, Appendices II & III.

- ^ Training Reserve at Long, Long Trail.

- ^ Maj H. McK. Annand, 'An Officer of the East York Militia, 1850', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 45, No 184 (Winter, 1967), pp. 231–3.

References

- Maj A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3b: New Army Divisions (30–41) and 63rd (R.N.) Division, London: HM Stationery Office, 1939/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-41-X.

- Ian F.W. Beckett, The Amateur Military Tradition 1558–1945, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-7190-2912-0.

- David Bilton, Hull in the Great War 1914–1919, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2015, ISBN 978-1-47382-314-3.

- Lindsay Boynton, The Elizabethan Militia 1558–1638, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1967.

- Steve Brown, 'Home Guard: The Forces to Meet the Expected French Invasion/1 September 1805' at The Napoleon Series (archived at the Wayback Machine).

- Lt-Col Sir John M. Burgoyne, Bart, Regimental Records of the Bedfordshire Militia 1759–1884, London: W.H. Allen, 1884.

- Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, 100th Edn, London, 1953.

- C.G. Cruickshank, Elizabeth's Army, 2nd Edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Col John K. Dunlop, The Development of the British Army 1899–1914, London: Methuen, 1938.

- Mark Charles Fissell, The Bishops' Wars: Charles I's campaigns against Scotland 1638–1640, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-521-34520-0.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol I, 2nd Edn, London: Macmillan, 1910.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol II, London: Macmillan, 1899.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol III, 2nd Edn, London: Macmillan, 1911.

- J.B.M. Frederick, Lineage Book of British Land Forces 1660–1978, Vol I, Wakefield: Microform Academic, 1984, ISBN 1-85117-007-3.

- Lt-Col James Moncrieff Grierson (Col Peter S. Walton, ed.), Scarlet into Khaki: The British Army on the Eve of the Boer War, London: Sampson Low, 1899/London: Greenhill, 1988, ISBN 0-947898-81-6.

- H.G. Hart, The New Annual Army List (various dates from 1840).

- Col George Jackson Hay, An Epitomized History of the Militia (The Constitutional Force), London:United Service Gazette, 1905/Ray Westlake Military Books, 1987 Archived 11 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 0-9508530-7-0.

- Richard Holmes, Soldiers: Army Lives and Loyalties from Redcoats to Dusty Warriors, London: HarperPress, 2011, ISBN 978-0-00-722570-5.

- Brig E.A. James, British Regiments 1914–18, Samson Books 1978/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2001, ISBN 978-1-84342-197-9.

- Roger Knight, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory 1793–1815', London: Allen Lane, 2013/Penguin, 2014, ISBN 978-0-141-03894-0.

- Norman E.H. Litchfield, The Militia Artillery 1852–1909 (Their Lineage, Uniforms and Badges), Nottingham: Sherwood Press, 1987, ISBN 0-9508205-1-2.

- F.W. Maitland, The Constitutional History of England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1931.

- Col R.W.S. Norfolk, Militia, Yeomanry and Volunteer Forces of the East Riding 1689–1908, York: East Yorkshire Local History Society, 1965.

- Col H.C.B. Rogers, Battles and Generals of the Civil Wars 1642–1651, London: Seeley Service 1968.

- Edward M. Spiers, The Army and Society 1815–1914, London: Longmans, 1980, ISBN 0-582-48565-7.

- Edward M. Spiers, The Late Victorian Army 1868–1902, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992/Sandpiper Books, 1999, ISBN 0-7190-2659-8.

- Everard Wyrall, The East Yorkshire Regiment in the Great War 1914–1918, London: Harrison, 1928/Uckfield: Naval & Military, 2002, ISBN 978-1-84342-211-2.