Don Carlos

| Don Carlos | |

|---|---|

| Grand opera by Giuseppe Verdi | |

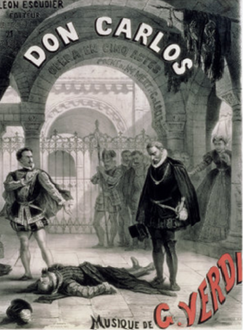

Carlo Cornaglia's depiction of Act IV (the original Act V) in the 1884 La Scala production | |

| Librettist | |

| Language | French, also in Italian translation |

| Based on | Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller (and incidents borrowed from a contemporary play by Eugène Cormon) |

| Premiere | 11 March 1867 Salle Le Peletier (Paris Opéra) |

Don Carlos[1] is an 1867 five-act grand opéra composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle. Its basis is Friedrich Schiller's play Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien, but it borrows from Eugène Cormon's play Philippe II, Roi d'Espagne,[2] as well. It is often performed in Italian translation, as Don Carlo.

The plot recounts conflicts in the life of Carlos, Prince of Asturias (1545–1568). Though he was betrothed to Elisabeth of Valois, part of the peace treaty ending the Italian War of 1551–59 between the Houses of Habsburg and Valois demanded that she be married instead to his father Philip II of Spain. It was commissioned and produced by the Théâtre Impérial de l'Opéra (Paris Opera) and given its premiere at the Salle Le Peletier on 11 March 1867.

The first performance in Italian was given at Covent Garden in London in June 1867. The first performance in Italy was in Bologna in October 1867, also in Italian translation. After some revisions by Verdi, it was performed in Italian in Naples in November/December 1872. Verdi was also responsible for a short four-act "Milan version" in which the first act was removed and the ballet omitted (performed in Milan in January 1884 in Italian translation) but also apparently approved a five-act "Modena version" in which the first act was restored but the ballet still omitted (performed in Modena in December 1886, also in Italian translation). Around 1970, substantial passages of music cut before the premiere were discovered in Paris archives, giving rise to at least one additional version that can be ascribed to Verdi: the version he prepared for the Paris Opera in 1866, before any cuts were made.[3] No other Verdi opera exists in so many authentic versions. At its full length (including the ballet and the cuts made before the first performance), it contains close to four hours of music and is Verdi's longest opera.[4]

Composition history

Pre-première cuts and first published edition

Verdi made a number of cuts in 1866, after finishing the opera but before composing the ballet, simply because the work was becoming too long.[4] These were a duet for Elisabeth and Eboli in Act 4, Scene 1; a duet for Carlos and the King after the death of Posa in Act 4, Scene 2;[5] and an exchange between Elisabeth and Eboli during the insurrection in the same scene.

After the ballet had been composed, it emerged during the 1867 rehearsal period that, without further cuts, the opera would not finish before midnight (the time by which patrons would need to leave in order to catch the last trains to the Paris suburbs). Verdi then authorised some further cuts, which were, firstly, the introduction to Act 1 (with a chorus of woodcutters and their wives, and including the first appearance of Elisabeth); secondly, a short entry solo for Posa (J'étais en Flandres) in Act 2, Scene 1; and, thirdly, part of the dialogue between the King and Posa at the end of Act 2, Scene 2.[6]

The opera was first published as given at the première and consisted of Verdi's original conception, without the music of the above-named cuts, but with the ballet.

In 1969, at a Verdi congress in Verona, the American musicologist David Rosen presented the missing section from the Philip-Posa duet from the end of Act 2, which he had found folded down in the conductor's copy of the score. Other pages with cuts had simply been removed from the autograph score and the conductor's copy. Shortly thereafter, the British music critic Andrew Porter found most of these other cut passages could be reconstructed from the individual parts, in which the pages with the "lost" music had been either "pasted, pinned or stitched down." In all, 21 minutes of missing music was restored.[7] Nearly all of the known music Verdi composed for the opera, including the pre-première cuts and later revisions, can be found in an integral edition prepared by the German musicologist Ursula Günther, first published in 1980[8] and in a second, revised version in 1986.[9]

Performance history

19th century

As Don Carlos in French

After the première and before leaving Paris, Verdi authorised the Opéra authorities to end Act 4, Scene 2 with the death of Posa (thereby omitting the insurrection scene) if they thought fit. This was done, beginning with the second performance on 13 March, after his departure. Further (unauthorised) cuts were apparently made during the remaining performances.[10] Despite a grandiose production designed by scenic artists Charles-Antoine Cambon and Joseph Thierry (Acts I and III), Édouard Desplechin and Jean-Baptiste Lavastre (Acts II and V), and Auguste Alfred Rubé and Philippe Chaperon (Act IV), it appears to have been a "problem opera" for the Opéra—it disappeared from its repertoire after 1869.[11]

- 1867 Paris premiere

- Marie Sasse as Elisabeth

- Costume design for Charles V, act 5

- Poster depicting the death of Rodrigo in the King's presence

As Don Carlo in an Italian translation

It was common practice at the time for most theatres (other than those in French-speaking communities) to perform operas in Italian,[12] and an Italian translation of Don Carlos was prepared in the autumn of 1866 by Achille de Lauzières.[13] On 18 November 1866 Verdi wrote to Giovanni Ricordi, offering the Milan publisher the Italian rights, but insisting that the opera:

- must be performed in its entirety as it will be performed for the first time at the Paris Opéra. Don Carlos is an opera in five acts with ballet: if nevertheless the management of Italian theatres would like to pair it with a different ballet, this must be placed either before or after the uncut opera, never in the middle, following the barbarous custom of our day.[14]

However, the Italian translation was first performed not in Italy but in London at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden on 4 June 1867, where it was produced and conducted by Michael Costa. However, it was not as Verdi desired; the opera was given in a cut and altered form, with the first act being removed, the ballet in Act 3 being omitted, and Carlo's aria Io la vidi (originally in Act 1) being moved to Act 3, just before the terzetto. Additionally, the duet between Philip and the Inquisitor was shortened by four lines, and Elisabeth's aria in Act 5 consisted only of part of the middle section and the reprise. The production was initially considered a success, and Verdi sent a congratulatory note to Costa. Later when he learned of the alterations, Verdi was greatly irritated, but Costa's version anticipated revisions Verdi himself would make a few years later in 1882–83.[15]

The Italian premiere on 27 October 1867 at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna, conducted by Verdi's close friend Angelo Mariani, was an "instant success", and this version, although produced in Verdi's absence, was more complete and included the ballet.[16] For the Rome premiere on 9 February 1868 at the Teatro Apollo, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Papal censor changed the Inquisitor into a Gran Cancelliere (Grand Chancellor) and the Monk/Emperor into a Solitario (Recluse).

This version of the opera was first performed in Milan at La Scala on 25 March 1868, and prestige productions in most other Italian opera houses followed, but it did not become a popular success. The length was a particular problem, and subsequent performances were generally heavily cut. The first production in Naples in 1871 was indisputably a failure.[16][17]

1872 revisions for Naples

Following the unsuccessful performance in Naples in 1871, Verdi was persuaded to visit the city for further performances in November / December 1872,[18] and he made two more modifications to the score: (a) a revision of the closing two-thirds of the Philippe-Rodrigue duet in Act 2, Scene 2 (to Italian verses, almost certainly by Antonio Ghislanzoni[19]), which replaced some of the previously cut material, and (b) the removal of the allegro marziale section of the final Elisabeth-Carlos duet (replaced with an 8-bar patch).[20] These are the only portions of the opera that were composed to an Italian rather than a French text.[19] According to Julian Budden, Verdi "was to regret both modifications".[21] Ricordi incorporated the revisions into later prints of the opera without changing the plate numbers. This subsequently confused some authors, e.g. Francis Toye and Ernest Newman, who dated them to 1883.[22]

1882/83 and 1886 revisions: "Milan version" and "Modena version"

The idea of reducing the scope and scale of Don Carlos had originally come to Verdi in 1875, partly as a result of his having heard reports of productions, such as Costa's, which had removed Act 1 and the ballet and introduced cuts to other parts of the opera. By April 1882, he was in Paris where he was ready to make changes. He was already familiar with the work of Charles-Louis-Étienne Nuitter, who had worked on French translations of Macbeth, La forza del destino and Aida with du Locle, and the three proceeded to spend nine months on major revisions of the French text and the music to create a four-act version. This omitted Act 1 and the ballet, and was completed by March 1883.[23] An Italian translation of this revised French text, re-using much of the original 1866 translation by de Lauzières, was made by Angelo Zanardini. The La Scala première of the 1883 revised version took place on 10 January 1884 in Italian.[24]

Although Verdi had accepted the need to remove the first act, it seems that he changed his mind and allowed a performance which presented the "Fontainebleau" first act along with the revised four-act version. It was given on 29 December 1886 in Modena, and has become known as the "Modena version", which was published by Ricordi as "a new edition in five acts without ballet".[25]

20th century and beyond

In Italian

Performances of Don Carlo in the first half of the twentieth century were rare, but in the post Second World War period it has been regularly performed, particularly in the four-act 1884 "Milan version" in Italian. In 1950, to open Rudolf Bing's first season as director of the Metropolitan Opera, the four-act version was performed without the ballet in a production by Margaret Webster with Jussi Björling in the title role, Delia Rigal as Elizabeth, Robert Merrill as Rodrigo, Fedora Barbieri as Eboli, Cesare Siepi as Philip II and Jerome Hines as the Grand Inquisitor. This version was performed there until 1972.[26][27] The four-act version in Italian continued to be championed by conductors such as Herbert von Karajan (1978 audio recording[28] and 1986 video recording[29]) and Riccardo Muti (1992 video recording[30]).[31]

Also influential was a 1958 staging of the 1886 five-act "Modena version" in Italian by The Royal Opera company, Covent Garden, directed by Luchino Visconti and conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini. The cast included Jon Vickers as Don Carlo, Tito Gobbi as Rodrigo, Boris Christoff as King Phillip and Gré Brouwenstijn as Elizabeth.[32] This version has increasingly been performed elsewhere and has been recorded by, among others, Georg Solti and Giulini.

After the discovery of music cut before the premiere, conductors began performing five-act versions that included some of it. In 1973 at La Fenice, Georges Prêtre conducted a 5-act version in Italian without the ballet that included the discarded woodcutters scene, the first Carlo-Rodrigo duet in a hybrid beginning with the Paris edition but ending with the Milan revision, the discarded Elisabeth-Eboli duet from Act 4, and the Paris finale.[33] In 1975, Charles Mackerras conducted an expanded and modified five-act version (with Verdi's original prelude, the woodcutters' scene and the original Paris ending) in an English translation for English National Opera at the London Coliseum. In 1978, Claudio Abbado mounted an expanded five-act version in Italian at La Scala. The cast included Mirella Freni as Elizabeth, Elena Obraztsova and Viorica Cortez as Eboli, José Carreras in the title role, Piero Cappuccilli as Rodrigo, Nicolai Ghiaurov as King Phillip, and Evgeny Nesterenko as the Grand Inquisitor.[34] On 5 February 1979, James Levine conducted an expanded five-act version in Italian at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The cast included Renata Scotto as Elizabeth, Marilyn Horne as Eboli, Giuseppe Giacomini as Don Carlo, Sherrill Milnes as Rodrigo, Nicolai Ghiaurov as King Philip, and James Morris as the Grand Inquisitor.[35][36][37]

Today, as translated into Italian and presented in four-act and five-act versions, the opera has become part of the standard repertory.

In French

Stagings and broadcasts of five-act French versions of the opera have become more frequent in the later 20th and into the 21st century. Up to 1973, these productions consisted of the revised and abridged four-act score of 1882–83 prefaced by the shortened, revised Act 1 set in Fontainebleau.[7] A radio broadcast by ORTF in France was given in 1967 with a nearly all-French cast, with the exception of the Italian Matteo Manuguerra as Rodrigue. A five-act French version was performed at La Scala Milan in 1970.

On 22 May 1973, the Opera Company of Boston under the direction of Sarah Caldwell presented a nearly complete five-act French version which included the 21 minutes of music cut before the premiere, but not the ballet. The 1867 version was used, since the restored music does not easily fit with the 1886 revised version. The cast included John Alexander in the title role, the French-Canadian Édith Tremblay as Élisabeth, the French singer Michèle Vilma as Princess Eboli, William Dooley as Rodrigue and Donald Gramm as Philippe. According to Andrew Porter, the Boston production was "the first performance, ever, of the immense opera that Verdi prepared in 1867; and in doing so it opened a new chapter in the stage history of the piece."[7][38]

The BBC Concert Orchestra under John Matheson broadcast the opera in June 1973 with the roles of Don Carlos sung by André Turp, Philippe II by Joseph Rouleau, and Rodrigue by Robert Savoie. Julian Budden comments that "this was the first complete performance of what could be called the 1866 conception in French with the addition of the ballet."[39]

Several notable productions of five-act French versions have been mounted more recently. A five-act French version was performed by the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels in 1983.[40] A co-production between the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris and the Royal Opera in London in 1996 used Andrew Porter as a consultant and was a "judicious mixture" of music from the 1866 original and the 1883 revision.[26][41] The production, staged by Luc Bondy, was also shared with the opera houses in Brussels, Nice and Lyon. The performance by the Paris cast (March 1996), was conducted by Antonio Pappano with Roberto Alagna as Don Carlos, Karita Mattila as Elisabeth, Thomas Hampson as Rodrigue, José Van Dam as Philippe II and Waltraud Meier as Eboli. It was recorded on videotape and is now available in a remastered HD video format.[26][42][43]

A Vienna State Opera production, staged by Peter Konwitschny and performed in Vienna in October 2004, included all of the music excised during the Paris rehearsal period plus the ballet. Patrick O'Connor, writing in the Gramophone magazine, reports the ballet was "staged as 'Eboli's Dream'. She and Don Carlos are living in suburban bliss, and have Philip and Elisabeth round for a pizza, delivered by Rodrigo. Musically, the performance, apart from the Auto-da-fé scene, has a lot going for it under the direction of Bertrand de Billy."[44] A DVD video recording is available.[45]

On 17 September 2005 a co-production directed by John Caird of the largely uncut Paris version in French between the Welsh National Opera and the Canadian Opera Company (Toronto) was premiered by the WNO at the Wales Millennium Center. The performance was conducted by Carlo Rizzi with Nuccia Focile as Elizabeth, Paul Charles Clarke as Don Carlos, Scott Hendricks as Rodrigue, Guang Yang as Eboli, Andrea Silvestrelli as Philippe II, and Daniel Sumegi as the Grand Inquisitor. The production was taken on tour to Edinburgh, Oxford, Birmingham, Bristol, Southampton and Liverpool. It was performed by the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto in October/November 2007 with a different cast. The production was performed several times by the Houston Grand Opera from 13 April 2012 until 28 April.[46] The Houston production was conducted by Patrick Summers with Brandon Jovanovich as Don Carlos, Tamara Wilson as Elizabeth, Andrea Silvestrelli as Philippe II, Christine Goerke as Eboli, Scott Hendricks as Rodrigue and Samuel Ramey as the Grand Inquisitor.[47][48][49][50][51]

In 2017, the Opéra National de Paris performed the 1866 French version (before the ballet was composed) in a production staged by Krzysztof Warlikowski at the Bastille. Conducted by Philippe Jordan, the cast included Jonas Kaufmann as Don Carlos, Sonya Yoncheva as Elisabeth, Ludovic Tézier as Rodrigue, Ildar Abdrazakov as Philippe II and Elīna Garanča as Eboli.[52] The Metropolitan Opera presented the opera in French for the first time in 2022 in the Modena version, with tenor Matthew Polenzani in the title role.[53]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast 11 March 1867[54][55] (Conductor: François George-Hainl) |

Revised version Premiere cast 10 January 1884[54] (Conductor: Franco Faccio)[56] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philippe II (Filippo II / Philip II), the King of Spain, son of Charles V and father of Don Carlos | bass | Louis-Henri Obin | Alessandro Silvestri |

| Don Carlos (Don Carlo), Infante of Spain, son and heir to the King | tenor | Jean Morère | Francesco Tamagno |

| Rodrigue (Rodrigo), Marquis of Posa, a friend of the Infante Don Carlos | baritone | Jean-Baptiste Faure | Paul Lhérie |

| Le Grand Inquisiteur (The Grand Inquisitor)[57] | bass | Joseph David | Francesco Navarrini |

| Élisabeth de Valois (Elisabeth of Valois), a French princess initially betrothed to Don Carlos but then married to King Philip | soprano | Marie-Constance Sass | Abigaille Bruschi-Chiatti |

| Princess Eboli, an aristocrat in court | mezzo-soprano | Pauline Guéymard-Lauters | Giuseppina Pasqua |

| A monk, who at the end of Act 5 appears as Charles-Quint (Emperor Charles V), thought to be dead[58] | bass | Armand Castelmary | Leopoldo Cromberg |

| Thibault (Tebaldo), page to Elisabeth | soprano (en travesti) | Leonia Levielly | Amelia Garten |

| A Voice from Heaven | soprano | ||

| The Count of Lerma, a Spanish delegate to France | tenor | Gaspard | Angelo Fiorentini |

| Royal Herald | tenor | Mermant | Angelo Fiorentini |

| Countess of Aremberg, a lady-in-waiting to Elisabeth | silent | Dominique | Angelina Pirola |

| Flemish envoys, Inquisitors, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Spanish Court, the people, Pages, Guards, Monks, Soldiers – chorus | |||

Synopsis

- [This synopsis is based on the original five-act version composed for Paris and completed in 1866. Important changes for subsequent versions are noted in indented brackets. First lines of arias, etc., are given in French and Italian].

Act 1

- [This act was omitted in the 1883 revision]

The Forest of Fontainebleau, France in winter

A prelude and chorus of woodcutters and their wives is heard. They complain of their hard life, made worse by war with Spain. Elisabeth, daughter of the King of France, arrives with her attendants. She reassures the people that her impending marriage to Don Carlos, Infante and son of Philip II, King of Spain, will bring the war to an end, and departs.

- [The preceding prelude and chorus of woodcutters was cut before the Paris première and replaced by a short scene in which Elisabeth crosses the stage and hands out money to the woodcutters; she exits without singing. The prelude and chorus of woodcutters was also omitted when Act 1 was restored in the 1886 five-act Modena version.]

Carlos, coming out from hiding, has seen Elisabeth and fallen in love with her (Aria: "Je l'ai vue" / "Io la vidi"). When she reappears, he initially pretends to be a member of the Count of Lerma's delegation. She asks him about Don Carlos, whom she has not yet met. Before long, Carlos reveals his true identity and his feelings, which she reciprocates (Duet: "De quels transports poignants et doux" / "Di quale amor, di quanto ardor"). A cannon-shot signifies that peace has been declared between Spain and France. Thibault appears and gives Elisabeth the surprising news that her hand is to be claimed not by Carlos but by his father, Philip. When Lerma and his followers confirm this, Elisabeth is devastated but feels bound to accept, in order to consolidate the peace. She departs for Spain, leaving Carlos equally devastated.

Act 2

- [This is Act 1 in the 1883 revision]

Scene 1: The monastery of Saint-Just (San Jerónimo de Yuste) in Spain

The scene takes place soon after King Philip II and Elisabeth have married. Monks pray before the tomb of the former Emperor Charles V ("Carlo Quinto"). The monks' leader proclaims that the Emperor was proud but has been humbled through error.

Don Carlos enters, anguished that the woman he loves is now his stepmother.

- [In the 1883 revision, he sings a revised version of the aria "Je l'ai vue" / "Io la vidi", which was salvaged from the omitted first act but with some different music and different text to reflect his current situation. In the four-act version he already knows that he cannot marry Elisabeth. In the original, when singing the aria, he was still expecting to marry her]

When Carlos pauses in his lament, the leader of the monks proclaims that the turbulence of the world persists even in sacred places; we cannot rest except in Heaven. The sound of his voice frightens Carlos, who thinks it sounds like that of the Emperor Charles V. Carlos further notices that the monk physically resembles the Emperor, and recalls hearing rumors that the Emperor's ghost haunts the monastery.

Carlos' dear friend Rodrigue, Marquis of Posa, who has just arrived from the oppressed land of Flanders, enters. The two greet each other joyfully (Aria: "J'étais en Flandres").

Rodrigue asks for the Infante's aid on behalf of the suffering people there. Carlos reveals that he loves his stepmother. Rodrigue is first shocked, but then sympathetic. He encourages Carlos to leave Spain and go to Flanders, and to forget his pain by focusing on political activity there. The two men swear eternal friendship (Duet: "Dieu, tu semas dans nos âmes" / "Dio, che nell'alma infondere").

King Philip and his new wife, with their attendants, enter also to do homage at Charles V's tomb, while Don Carlos laments his lost love.

Scene 2: A garden near Saint-Just

Princess Eboli sings the Veil Song ("Au palais des fées" / "Nel giardin del bello") about a Moorish King trying to seduce an alluring veiled beauty, who turns out to be his own neglected wife. Elisabeth enters. Rodrigue gives her a letter from France, which covers a secret note from Don Carlos. At his urging (Aria: "L'Infant Carlos, notre espérance" / "Carlo ch'è sol il nostro amore"), Elisabeth agrees to see the Infante alone. Unaware of this relationship, Eboli infers that she, Eboli, is the one Don Carlos loves.

When they are alone, Don Carlos tells Elisabeth that he is miserable, and asks her to request the King to send him to Flanders. She promptly agrees, provoking Carlos to renew his declarations of love, which she piously rejects. Don Carlos exits in a frenzy, shouting that he must be under a curse. The King enters and becomes angry because the Queen is alone and unattended. His suspicions are insulting to her. He orders the lady-in-waiting who was meant to be attending her, the Countess of Aremberg, to return to France, prompting Elizabeth to sing a sorrowful farewell-aria. (Aria: "Oh ma chère compagne" / "Non pianger, mia compagna").

The King now approaches Rodrigue, with whose character and activism he is impressed, and offers to reward him for his loyalty and service. Rodrigue begs the King to stop oppressing the people of Flanders. The King calls Rodrigue's idealism unrealistic and warns that the Grand Inquisitor is watching him. The King confides in Rodrigue, telling him that he fears that Carlos is having an affair with Elisabeth. Rodrigue replies that Carlos is innocent, and offers to watch Elisabeth and to be responsible for her good behavior. The King gratefully accepts this offer, and again warns Rodrigue to beware of the Grand Inquisitor.

- [This dialogue was revised three times by Verdi.]

Act 3

- [This is Act 2 in the 1883 revision]

Scene 1: Evening in the Queen's garden in Madrid

Elisabeth is tired, and wishes to concentrate on the following day's coronation of the King. To avoid the divertissement planned for the evening, she exchanges masks with Eboli, assuming that thereby her absence will not be noticed, and leaves.

- [This scene was omitted from the 1883 revision]

- [In the première, the ballet (choreographed by Lucien Petipa and entitled "La Pérégrina") took place at this point]

At midnight, Don Carlos enters, clutching a note suggesting a tryst in the gardens. Although he thinks this is from Elisabeth, it is really from Eboli. Eboli, who still thinks Don Carlos loves her, enters. Don Carlos mistakes her for Elisabeth in the dark, and passionately declares his love. When he sees Eboli's face, he realizes his error and recoils from her. Eboli guesses his secret—that he was expecting the Queen, whom he loves. She threatens to tell the King that Elisabeth and Carlos are lovers. Carlos, terrified, begs for mercy. Rodrigue enters, and warns her not to cross him; he is the King's confidant. Eboli replies by hinting darkly that she is a formidable and dangerous foe, with power which Rodrigue does not yet know about. (Her power is that she is having an affair with the King, but she does not reveal this yet.) Rodrigue draws his dagger, intending to stab her to death, but reconsiders, spares her, and declares his trust in the Lord. Eboli exits in a vengeful rage. Rodrigue advises Carlos to entrust to him any sensitive, potentially incriminating political documents that he may have and, when Carlos agrees, they reaffirm their friendship.

Scene 2: In front of the Cathedral of Valladolid

Preparations are being made for an auto-da-fé, the public parade and burning of condemned heretics. While the people celebrate, monks drag the condemned to the woodpile. A royal procession follows, and the King addresses the populace, promising to protect them with fire and sword. Don Carlos enters with six Flemish envoys, who plead with the King for their country's freedom. Although the people and the court are sympathetic, the King, supported by the monks, orders his guards to arrest the envoys. Carlos demands that the King grant him authority to govern Flanders; the King scornfully refuses. Enraged, Carlos draws his sword against the King. The King calls for help but the guards will not attack Don Carlos. Rodrigue realizes that actually attacking the King would be disastrous for Carlos. He steps forward and defuses the situation by taking Carlos' sword from him. Carlos, astonished, yields to his friend without resisting. Relieved and grateful, the King raises Rodrigue to the rank of Duke. The guards arrest Carlos, the monks fire the woodpile, and as the flames start to rise, a heavenly voice can be heard promising heavenly peace to the condemned souls.

Act 4

- [This is Act 3 in the 1883 revision]

Scene 1: Dawn in King Philip's study in Madrid

Alone and suffering from insomnia, the King, in a reverie, laments that Elisabeth has never loved him, that his position means that he has to be eternally vigilant and that he will only sleep properly when he is in his tomb in the Escorial (Aria: "Elle ne m'aime pas" / "Ella giammai m'amò"). The blind, ninety-year-old Grand Inquisitor is announced and shuffles into the King's apartment. When the King asks if the Church will object to him putting his own son to death, the Inquisitor replies that the King will be in good company: God sacrificed His own son. In return for his support, the Inquisitor demands that the King have Rodrigue killed. The King refuses at first to kill his friend, whom he admires and likes. However, the Grand Inquisitor reminds the King that the Inquisition can take down any king; he has created and destroyed other rulers before. Frightened and overwhelmed, the King begs the Grand Inquisitor to forget about the past discussion. The latter replies "Peut-être" / "Forse!" – perhaps! – and leaves. The King bitterly muses on his helplessness to oppose the Church.

Elisabeth enters, alarmed at the apparent theft of her jewel casket.[59] However, the King produces it and points to the portrait of Don Carlos which it contains, accusing her of adultery. She protests her innocence but, when the King threatens her, she faints. In response to his calls for help, into the chamber come Eboli and Rodrigue. Their laments of suspicion cause the King to realize that he has been wrong to suspect his wife (Quartet: "Maudit soit le soupçon infâme" / "Ah, sia maledetto, il rio sospetto"[60]). Aside, Rodrigue resolves to save Carlos, though it may mean his own death. Eboli feels remorse for betraying Elisabeth; the latter, recovering, expresses her despair.

- [The quartet was revised by Verdi in 1883 and begins: "Maudit soit, maudit le soupçon infâme" / "Ah! sii maledetto, sospetto fatale".[61]]

Elisabeth and Eboli are left together. Eboli confesses that it was she who told the King that Elisabeth and Carlos were having an affair, for revenge against Carlos for having rejected her. This is followed by the duet "J'ai tout compris". Eboli also confesses that she herself is guilty of that which she accused the Queen, and has become the King's mistress. Elisabeth leaves, and the Count di Lerma orders Eboli to choose between exile or the convent, then leaves.[62]

- [At the premiere, the duet "J'ai tout compris" and Eboli's second confession, of her affair with the king, were omitted. Elisabeth orders Eboli to choose between exile or the convent immediately after Eboli's first confession.[63] In 1883, the duet was omitted, but Eboli's second confession was reinstated in a revised version, and Elisabeth remains on stage to sing the Count di Lerma's lines.[64]]

Eboli, left alone, curses her own beauty and pride, and resolves to make amends by trying to save Carlos from the Inquisition (Aria: "O don fatal" / "O don fatale").[65]

Scene 2: A prison

Don Carlos has been imprisoned. Rodrigue arrives and tells Carlos that he (Rodrigue) has saved Carlos from being executed, by allowing himself (Rodrigue) to be incriminated by the politically sensitive documents which he had obtained from Carlos earlier (Aria, part 1: "C'est mon jour suprême" / "Per me giunto è il dì supremo"). A shadowy figure appears—one of the Grand Inquisitor's assassins—and shoots Rodrigue in the chest. As he dies, Rodrigue tells Carlos that Elisabeth will meet him at Saint-Just the following day. He adds that he is content to die if his friend can save Flanders and rule over a happier Spain (Aria, part 2: "Ah, je meurs, l'âme joyeuse" / "Io morrò, ma lieto in core"). At that moment, the King enters, offering his son freedom, as Rodrigue had arranged. Carlos repulses him for having murdered Rodrigue. The King sees that Rodrigue is dead and cries out in sorrow.

- [Duet: Carlos and the King- "Qui me rendra ce mort ?" /"Chi rende a me quest'uom" It was cut before the première and, following it, Verdi authorized its optional removal. The music was later re-used by Verdi for the Lacrimosa of his Messa da Requiem of 1874]

Bells ring as Elisabeth and Eboli enter. The crowd pushes its way into the prison and threatens the King, demanding the release of Carlos. In the confusion, Eboli escapes with Carlos. The people are brave enough at first in the presence of the King, but they are terrified by the arrival of the Grand Inquisitor, and instantly obey his angry command to quiet down and pay homage to the King.

- [After the première, some productions ended this act with the death of Rodrigue. However, in 1883 Verdi provided a much shortened version of the insurrection, as he felt that otherwise it would not be clear how Eboli had fulfilled her promise to rescue Carlos]

Act 5

- [This is Act 4 in the 1883 revision]

The moonlit monastery of Yuste

Elisabeth kneels before the tomb of Charles V. She is committed to help Don Carlos on his way to fulfill his destiny in Flanders, but she herself longs only for death (Aria: "Toi qui sus le néant" / "Tu che le vanità"). Carlos appears and tells her that he has overcome his desire for her; he now loves her honorably, as a son loves his mother. They say a final farewell, promising to meet again in Heaven (Duet: "Au revoir dans un monde où la vie est meilleure" / "Ma lassù ci vedremo in un mondo migliore").

- [This duet was twice revised by Verdi]

The King and the Grand Inquisitor enter, with several armed guards. The King infers that Carlos and Elisabeth have been lovers and demands that they both be immediately killed in a double sacrifice. The Inquisitor confirms that the Inquisition will do its duty. A short summary trial follows, confirming Carlos's putative culpability.

- [The trial was omitted in 1883 and does not occur on any commercially available audio recording, although it was performed at La Scala in 1978.[citation needed] It was performed in Vienna in 2004 and recorded on video.[45]]

Carlos, cries "Ah, God will avenge me, this tribunal of blood, His hand will crush."[66] Defending himself, Carlos retreats towards the tomb of Charles V. The gate opens, the Monk appears, draws Carlos into his arms, covers him with his coat and sings: "My son, the pains of the earth still follow us in this place, the peace your heart hopes for is found only with God."[67] The King and the Inquisitor recognize the Monk's voice: he is the King's father, Charles V, who was believed dead. As the curtain slowly falls, the Monk leads the distraught Carlos into the cloister to the chanting of monks in the chapel that "Charles V, the august Emperor is naught but ash and dust."[68] The opera concludes softly with pianissimo chords and tremolos played by the strings.[45][69]

- [The ending was revised in 1883, with the Monk singing a tone higher. The score explicitly indicates he is Charles V with royal robe and crown, and the chanting of the monks is no longer sung, but "thundered out as a brass chorale."[70][71]]

Instrumentation

Except as noted, the instrumentation shown here is from the Edizione integrale, second edition, edited by Ursula Günther.[72]

- Woodwinds: 3 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons, contrabassoon

- Brass: 4 horns, 2 cornets, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, ophicleide

- Percussion: timpani, bass drum, triangle, bells, cannon, tambourine, castanets

- Other: harp, harmonium

- Stage band:[73] Offstage horns (left and right) in E-flat and B-flat, D clarinet, 2 clarinets in A, 2 flugelhorns, 2 trumpets in D, 4 horns in D, 2 tubas, 2 trombones, 2 bass tubas

- Strings: violins, violas, cellos, double basses

Recordings

See also

References

Notes

- ^ In the title of the opera and the play, "Don" is used as the Spanish honorific.

- ^ Kimbell 2001, in Holden p. 1002. Budden 1981, pp. 15–16, reinforces this with details of the play.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. XX–XXI.

- ^ a b Budden 1981, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Kimbell 2001, p. 1002, notes that "some of the deleted material from this served as the seed for the 'Lacrymosa' in the Requiem".

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Porter, Andrew. "Musical Events: Proper Bostonian" The New Yorker, 2 June 1973, pp. 102–108.

- ^ Porter 1982.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 25–26.

- ^ Kimbell 2001, in Holden, p. 1003.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 156.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 26; for the Italian translation by Achille de Lauzières, see OCLC 21815071 (vocal score); OCLC 777337258 (libretto).

- ^ Quoted and translated in Budden 1981, p. 27.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 27.

- ^ a b Budden 1981, p. 28.

- ^ Walker 1962, p. 326.

- ^ Walker 1962, p. 417.

- ^ a b Porter 1982, p. 368.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. XX, 263–276 (a), 623 (b). Budden 1981, pp. 28–29. Porter 1982, p. 362.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 29.

- ^ Porter 1982, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Budden 1981, pp. 31–38.

- ^ 1884 Milan version: Notice de spectacle at BnF.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 39.

- ^ a b c David Stevens (6 March 1996). "'Don Carlos,' Early and Late", The New York Times.

- ^ "Don Carlo (6 November 1950) Telecast, Met Opera Archive.

- ^ Don Carlo, Opera in 4 acts; originally in 5, Music CD, OCLC 53213864. #96 at operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- ^ Don Carlos: opera in four acts, DVD video, OCLC 52824860. #120 at operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- ^ The Gramophone Classical Music Guide, 2008, pp. 1133–1134. Don Carlo: dramma lirica in quattro atti, DVD video, OCLC 1048057459. #128 at operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- ^ The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music, 2008, pp. 1460–1461.

- ^ Don Carlos, 9 May 1958, Evening Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Opera House Collections Online, Performance Database, accessed Oct. 1 2013.

- ^ #74 at operadis-opera-discography.org.uk. "Indifferently recorded, frantically conducted".

- ^ Kobbé 1997, p. 901.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (4 February 1979). Music View: 'Don Carlo'—Great But Difficult", The New York Times. The production added the Prelude and Introduction to Act 1, music cut before the 1867 premiere.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (6 February 1979). "Opera: New Production Of ‘Don Carlo’ at the Met", The New York Times.

- ^ Met performance of 5 February 1979 at the Met Opera Archive.

- ^ Kessler 2008, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 155.

- ^ #108 at operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- ^ "Don Carlos". ROH Collections. Archived from the original on 2018-03-27. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ William R. Braun (January 2004), "Recordings, Video. Verdi: Don Carlos, Théâtre du Châtelet"[permanent dead link], Opera News.

- ^ Don Carlos. Kultur Bluray video [2014]. OCLC 880331555.

- ^ Patrick O'Connor (January 2008). "Verdi, Don Carlos. Verdi's music gets respect but visually this 'complete' Carlos is incomplete..." Gramophone, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Don Carlos. TDK, 2007. OCLC 244369432, 1252604603. Arthaus Musik, 2010. OCLC 914649838.

- ^ Archive copy of "Don Carlos, Grand opera in 5 Acts", originally at johncaird.com.

- ^ Everett Evans (17 April 2012), "HGO rises to the occasion with 'Don Carlos'" at chron.com. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ William Burnett (17 April 2012), "Review: Brandon Jovanovich Triumphant in Historic “Don Carlos” Production – Houston Grand Opera, April 13, 2012" at operawarhorses.com. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Gregory Barnett (4/13/12), "Don Carlos, Houston Grand Opera, 4/13/12" Archived 2022-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, Opera News. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Associated Press (23 April 2012), "A less-cut operatic 'Don Carlos' in Houston", Deseret News. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Heidi Waleson (24 April 2012), "Soprano Showdown in Houston", The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Mudge, Stephen J. "Don Carlos". operanews.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ MOoD Detail Page, retrieved 2024-03-04

- ^ a b Budden 1981, p. 4.

- ^ "Don Carlos". Instituto Nazionale di Studi Verdiani. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Don Carlo, 10 January 1884". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ^ Diego, Cardinal de Espinosa at the time, but not mentioned as such in the opera

- ^ See p. 357 of the 1867 Escudier piano-vocal score.

- ^ For the premiere, the second eight measures of the orchestral introduction to Elisabeth's entry were omitted and the first half of the ninth measure slightly revised (Verdi; Günther 1986, p. 454–455). This change was retained in the 1883 revision (Verdi; Günther 1986, p. 504).

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. 467 (letter N) – 468.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. 513–521.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. 479–492.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. 493–497.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. 522–527.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, pp. 498–503. The orchestral introduction to the aria 'O don fatal' was slightly revised in the 1883 version (Verdi; Günther 1986, p. 527). The rest of the aria is essentially unchanged, but printed again (on pp. 527–532 in the 1986 edition), as Andrew Porter mentions in his review of the 1980 edition (Porter 1982, p. 367).

- ^ Don Carlos, 1867 libretto, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, p. 649: "Mon fils, les douleurs de la terre nous suivent encor dans ce lieu, la paix que votre coeur espère ne se trouve qu'auprès de Dieu!" These words differ from those in the printed libretto.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, p. 651: "Charles Quint, l'auguste Empereur n'est plus que cendre et que poussière." These words differ from those in the printed libretto.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, p. 651.

- ^ Budden 1981, p. 152.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, p. 669.

- ^ Verdi; Günther 1986, p. XXXVII.

- ^ The autograph score does not specify the instrumentation of the stage band, and Verdi notated the music at real pitch. For the 1867 Paris premiere, instruments made by Adolphe Sax were used (Verdi; Günther 1986, p. XXXVII). The instrumentation given here is from the Dover reprint (Verdi 2011, p. xii), which states the instrumentation is from the "authoritative Ricordi edition of Don Carlo" but is rarely used in its entirety.

Cited sources

- Budden, Julian (1981), The Operas of Verdi, Volume 3: From Don Carlos to Falstaff. London: Cassell. ISBN 9780304307401.

- Kimbell, David (2001), in Holden, Amanda (Ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam, 2001. ISBN 0-14-029312-4

- Kessler, Daniel (2008), Sarah Caldwell; The First Woman of Opera. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-6110-0.

- Parker, Roger (1998), "Don Carlos", in Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. One. London: Macmillan Publishers, Inc. 1998 ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5.

- Kobbé, Gustav (1997). The New Kobbé's Opera Book, edited by the Earl of Harewood and Antony Peattie. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780399143328.

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (1994), Verdi: A Biography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-313204-4.

- Porter, Andrew (1982), Review of: "Giuseppe Verdi. Don Carlos: Edizione integrale..., edited by Ursula Günther (and Lucian Petazzoni). 1980." Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 35, no. 2 (Summer, 1982), pp. 360–370. JSTOR 831152.

- Verdi, Giuseppe (2011). Don Carlos ("Don Carlo") in Full Score. The classic Italian translation authorized by the composer, published as DON CARLO in a revised five-act restoration, with notations for an alternative four-act version. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2001, 2011. ISBN 9780486413877. Dover states this is an unabridged republication of the work published by G. Ricordi, Milan, undated, as Giuseppe Verdi, Don Carlo—Partitura (Valevole per l'edizione in 4 e 5 atti).

- Verdi, Giuseppe; Ursula Günther, editor (1986), Don Carlos, edizione integrale delle varie versioni in cinque e in quattro atti (comprendente gli inediti verdiani a cura di Ursula Günther). Second revision of the sources, prepared by Ursula Günther and Luciano Petazzoni. Piano-vocal score in two volumes with French and Italian text. Milan: Ricordi. Copyright 1974. OCLC 15625441.

- Walker, Frank (1962), The Man Verdi. New York: Knopf. OCLC 351014. London: Dent. OCLC 2737784. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press (1982 paperback reprint with a new introduction by Philip Gossett). ISBN 978-0-226-87132-5.

Other sources

- Batchelor, Jennifer (ed.) (1992), Don Carlos/Don Carlo, London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun. ISBN 0-7145-4208-3.

- De Van, Gilles (trans. Gilda Roberts) (1998), Verdi's Theater: Creating Drama Through Music. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14369-4 (hardback), ISBN 0-226-14370-8

- Gossett, Philip (2006), Divas and Scholar: Performing Italian Opera, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30482-5

- Martin, George, Verdi: His Music, Life and Times (1983), New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. ISBN 0-396-08196-7

- Osborne, Charles (1969), The Complete Operas of Verdi, New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1969. ISBN 0-306-80072-1

- Parker, Roger (2007), The New Grove Guide to Verdi and His Operas, Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531314-7

- Pistone, Danièle (1995), Nineteenth-Century Italian Opera: From Rossini to Puccini, Portland, OR: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-82-9

- Toye, Francis (1931), Giuseppe Verdi: His Life and Works, New York: Knopf, 1931

- Warrack, John and West, Ewan (1992), The Oxford Dictionary of Opera New York: OUP. ISBN 0-19-869164-5

- Werfel, Franz and Stefan, Paul (1973), Verdi: The Man and His Letters, New York, Vienna House. ISBN 0-8443-0088-8

External links

- Verdi: "The story" and "History" on giuseppeverdi.it

- 1867 French libretto at Google Books

- Libretto (Italian)

- Full musical score and vocal scores (Italian and French, 4-act and 5-act versions): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Visual evidence of the Parisian premiere on Gallica

- Aria list from aria-database.com

- Don Carlo (1960) at IMDb , Metropolitan Opera

- Don Carlos (1965) at IMDb , Deutsche Oper Berlin

- Don Carlo (1983, TV) at IMDb , The Metropolitan Opera Presents

- Don Carlo (1985) at IMDb , The Royal Opera

- Don Carlos (1986) at IMDb , Salzburg Easter Festival

- Don Carlos (1996) at IMDb , Théâtre du Châtelet

- Don Carlo (2010) at IMDb , The Royal Opera