Dixon, California

City of Dixon | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Dixon | |

| Nickname(s): | |

Location of Dixon in Solano County, California | |

| Coordinates: 38°26′57″N 121°49′37″W / 38.44917°N 121.82694°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Solano |

| Incorporated | March 30, 1878[4] |

| Named for | Thomas Dickson |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Steve Bird [5] |

| • city manager | Jim Lindley[6] |

| • State senator | Bill Dodd (D)[7] |

| • Assemblymember | Cecilia Aguiar-Curry (D)[7] |

| • U. S. rep. | Mike Thompson (D)[8] |

| Area | |

• Total | 7.20 sq mi (18.64 km2) |

| • Land | 7.10 sq mi (18.39 km2) |

| • Water | 0.10 sq mi (0.25 km2) 1.36% |

| Elevation | 62 ft (19 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 18,988 |

| • Density | 2,674.37/sq mi (1,032.53/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 95620 |

| Area code | 707 |

| FIPS code | 06-19402 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1655973, 2410343 |

| Website | www |

Dixon is a city in northern Solano County, California, United States, located 23 miles (37 km) from the state capital, Sacramento. It has a hot-summer mediterranean climate on the Köppen climate classification scale. Its population was 18,988 at the 2020 census.[11] Other nearby cities include Vacaville, Winters, Davis, Woodland, and Rio Vista.

History

The first semi-permanent European settlement to develop in the Dixon area emerged during the California Gold Rush of the mid-19th century when the community of Silveyville was founded in 1852 by Elijah Silvey[12] as a halfway point between the Pacific coast and the rich gold fields of Sacramento along a route commonly traveled by miners. In 1868, Central Pacific railroad came through the area and missed Silveyville by a few miles.[13] As a result, local leaders decided to physically relocate Silveyville closer to the tracks in order to enjoy the benefits of commerce and travel. One of the first buildings that still stands in Dixon from the 1871 move is the Dixon Methodist Church located at 209 N. Jefferson Street.[14]

Originally, the city was named "Dicksville" after Thomas Dickson who donated 10 acres of his land for the construction of a railroad depot following the completion of the tracks and subsequent relocation of Silveyville to the now-Dixon area.[12] However, when the first rail shipment of merchandise arrived from San Francisco in 1872, it was mistakenly addressed to "Dixon"—a name that has been used since, mainly out of simplicity.[12][14] Up to now, the urban landscape of the town can be seen to have developed mostly in between the railroad tracks and Interstate-80.

As of 2024 the Dixon city council consists of Steve Bird, Mayor, Kevin Johnson, Vice Mayor, representing District 3, Jim Ernest, representing District 1, Thom Bogue, representing District 2, and Don Hendershot, representing District 4.[15]

The city operates a municipal police and fire department, and water system & wastewater treatment plant.

Geography

Dixon is located at 38°26′57″N 121°49′37″W / 38.44917°N 121.82694°W (38.449108, -121.826872).[16]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.1 square miles (18 km2), of which, 7.0 square miles (18 km2) of it is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) of it (1.36%) is water.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 317 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,082 | — | |

| 1900 | 788 | −27.2% | |

| 1910 | 827 | 4.9% | |

| 1920 | 926 | 12.0% | |

| 1930 | 1,000 | 8.0% | |

| 1940 | 1,108 | 10.8% | |

| 1950 | 1,714 | 54.7% | |

| 1960 | 2,970 | 73.3% | |

| 1970 | 4,432 | 49.2% | |

| 1980 | 7,541 | 70.1% | |

| 1990 | 10,401 | 37.9% | |

| 2000 | 16,103 | 54.8% | |

| 2010 | 18,351 | 14.0% | |

| 2020 | 18,988 | 3.5% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 19,309 | 1.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[17] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[18] reported that Dixon had a population of 18,351. The population density was 2,587.7 inhabitants per square mile (999.1/km2). The racial makeup of Dixon was 13,023 (71.0%) White, 562 (3.1%) African American, 184 (1.0%) Native American, 671 (3.7%) Asian, 58 (0.3%) Pacific Islander, 2,838 (15.5%) from other races, and 1,015 (5.5%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7,426 persons (40.5%).

The Census reported that 100% of the population lived in households.

There were 5,856 households, out of which 2,773 (47.4%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 3,550 (60.6%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 790 (13.5%) had a female householder with no husband present, 339 (5.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 327 (5.6%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 26 (0.4%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 867 households (14.8%) were made up of individuals, and 301 (5.1%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.13. There were 4,679 families (79.9% of all households); the average family size was 3.47.

The population was spread out, with 5,349 people (29.1%) under the age of 18, 1,816 people (9.9%) aged 18 to 24, 5,026 people (27.4%) aged 25 to 44, 4,608 people (25.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 1,552 people (8.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.8 males.

There were 6,172 housing units at an average density of 870.3 units per square mile (336.0 units/km2), of which 3,902 (66.6%) were owner-occupied, and 1,954 (33.4%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.2%. 12,149 people (66.2% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 6,201 people (33.8%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

As of the census[19] of 2000, there were 16,103 people, 5,073 households, and 4,164 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,434.1 inhabitants per square mile (939.8/km2). There were 5,172 housing units at an average density of 781.8 units per square mile (301.9 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 70.51% White, 1.93% Black or African American, 0.99% Native American, 3.11% Asian, 0.30% Pacific Islander, 17.87% from other races, and 5.29% from two or more races. 33.62% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 5,073 households, out of which 47.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 67.0% were married couples living together, 9.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 17.9% were non-families. 13.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.17 and the average family size was 3.45.

In the city, the population is concentrated among adults 25 to 44 (32.2%) and children under age 18 (32%). Only 8.5% of the population is aged 18 to 24; 20.0% from 45 to 64; and 7.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $54,472, and the median income for a family was $58,849. Males had a median income of $42,286 versus $30,378 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,139. About 5.2% of families and 8.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.1% of those under age 18 and 6.6% of those age 65 or over.

Notable sites

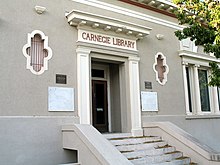

The Jackson Fay Brown House and the Dixon Carnegie library are on the National Register of Historic Places.[20]

As of 2014, Dixon residents Matt and Mark Cooley, owners of Cool Patch Pumpkins, hold the Guinness World Record for "largest maze, temporary corn/crop maze".[21][22] The maze measured 163,853.83 m2 or 40.489 acres.[23] In 2012, Cool Patch Pumpkins broke its own record with a 53-acre maze.[24] In 2014 Cool Patch Pumpkins again broke its own record by growing a 60-acre maze.[25]

A Milk Farm Restaurant sign, measuring 100 feet tall,[3] was built in May 1963[3] and still stands today at the intersection of State Route 113 and Interstate 80.[26]

Dixon is home to the Dixon May Fair, California's oldest fair.[27][28] The fair began in 1885 as a May Day celebration and predates the Solano County Fair which first occurred in 1949.[29] A stage on the fairground was named in honor of country singer Jon Pardi,[30] who grew up in Dixon.

Notable people

- Spencer Webb - was a tight end for the Oregon Ducks[31]

- Jon Pardi - Country music singer and songwriter[32]

- Nick Watney - Professional golfer[33]

- Dave Ball - Professional NFL player[34]

- Espinoza Paz - Mexican musician and composer[35]

- Joe Craven - Professional musician and music educator[36]

Transportation

Interstate 80 and California State Route 113 pass through Dixon.

The Union Pacific Railroad mainline between Oakland and Sacramento also passes through Dixon.[2] This line was owned by Southern Pacific Railroad until its merger with Union Pacific on September 11, 1996. The track was constructed in 1868 by the California Pacific Railroad.

Amtrak Capitol Corridor also passes through Dixon over the UP mainline but the nearest station stops are at Davis and Fairfield–Vacaville. Amtrak's California Zephyr and Coast Starlight also pass through Dixon without stopping.[2]

In 2006, the City of Dixon finished construction on a train station near downtown Dixon.[2] However, there are currently no scheduled stops at the station. The building has, for the time being, been converted to the city's Chamber of Commerce.[2]

The Dixon Readi-Ride is a dial-a-ride shuttlebus service. The Dixon Park & Ride[37] serves Fairfield and Suisun Transit route 30 which runs between Fairfield Transportation Center and downtown Sacramento.[38] The Dixon Readi-Ride a dial-a-ride service also stops here.[39] It has 89 parking spots. The bus service runs approximately 10 hours per day on route 30.[40]

Economy

Top employers

According to the city's 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[41] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dixon Unified School District | 346 |

| 2 | Walmart | 300 |

| 3 | Cardinal Health | 250 |

| 4 | Basalite | 193 |

| 5 | Altec Industries | 190 |

| 6 | Dixon Canning (Campbell's) | 182 |

| 7 | Superior Packing | 164 |

| 8 | City of Dixon | 156 |

| 9 | Gold Star Foods | 99 |

| 10 | First Northern Bank | 74 |

Dixon was the home of the Gymboree Corporation's only distribution center prior to the bankruptcy and closing of the company in 2019.[42]

Media

The Dixon Independent Voice was founded in 1993 (first as The Dixon Newspaper)[43] and is the main paper of circulation today.[44] It is published weekly and is owned by Messenger Publishing Group.[45] The Dixon Tribune newspaper was founded November 14, 1874.,[12] but ceased publication after its January 31, 2024 issue.[46]

Historically, the Voice of America ran a shortwave transmitter site that was formerly owned and operated by NBC. NBC built the site in 1944,[47] and it broadcast under the call signs KNBA, KNBH, KNBI, KNBC, and KNBX.[48] The station was closed between September 2, 1979, and October 1, 1983, and briefly reopened for Spanish language broadcasting until 1988.[48][49] The station served as a relay to both NBC International programming overseas, and as a relay of KNBR and its programming overseas, mostly the Pacific area.[50] There is also a military transmission site, the Dixon Naval Radio Transmitter Facility.[51]

Education

Dixon is served by the Dixon Unified School District, and also has a few private educational institutions.

High schools

- Dixon High School

- Maine Prairie High School (continuation school)

Middle schools

- Dixon Montessori Charter School

- John Knight Middle School (formerly known as C.A. Jacobs Middle School)

- Neighborhood Christian Middle School

Elementary schools

- Silveyville (closed as of 2008)

- Anderson

- Gretchen Higgins

- Tremont

- Neighborhood Christian School

- Dixon Montessori Charter School (now located in Silveyville facility)

- Easter Seals Special Education Center (shares Silveyville facility with DMCS)

References

- ^ "May 13, 2014 City Council Resolution". City of Dixon. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Bizjak, Tony (November 29, 2014). "Dixon's downtown depot: Will the train ever stop here?". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c Lucas, Greg (March 21, 2004). "DIXON / Inventor hopes grand plan to revive venerable I-80 roadside stop will fly / Milk Farm sign lured weary travelers for generations, but it's all that remains of longtime favorite". SFGate. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "City Council". Dixon, CA. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ "City Manager". Dixon, CA. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". Regents of the University of California. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ^ "Statewide Database". Zip Data Maps. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Dixon". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Dixon city, California". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Munro-Fraser, J.P. (1879). History of Solano County...and histories of its cities, towns. Wood, Alley & co. pp. 280–287. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Once-bustling Silveyville a town that disappeared". January 6, 2013.

- ^ a b "Visitors Guide". Dixon Chamber of Commerce online. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ "City Council". City of Dixon. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Dixon city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Ratcheting Up Solano Pride". Benicia magazine. March 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ "Get lost in Cool Patch Pumpkins corn maze, now open". Woodland Daily Democrat. September 22, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Flores, Hilda (October 1, 2021). "Here are some corn mazes in the Sacramento area to explore this fall". KCRA3. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Largest maze, temporary corn/crop maze".

- ^ "Cool Patch Pumpkins Corn Maze". Archived from the original on March 19, 2013.

- ^ Cruzen, Imani (August 4, 2022). "'World's largest' corn maze near St. Cloud features Halloween characters, 110-acres". St. Cloud Times. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Paul, Bil (June 14, 2011). "Dixon Then and Now: The Milk Farm Was Dixon's Nut Tree". Patch. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Spencer, Karen (May 2, 2016). "Dixon May Fair will be buzzing with excitement". Davis Enterprise. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Green, Kevin (March 24, 2015). "Exhibit guidebook outlines Dixon May Fair entries". Fairfield Daily Republic. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Maginnis-Honey, Amy (May 9, 2013). "Dixon May Fair evolved from annual event that began in 1876". Fairfield Daily Republic. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Sestanovich, Nick (December 8, 2021). "Dixon City Council approves naming plaza stage after Jon Pardi". Vacaville Reporter. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Davidson, Joe (July 30, 2022). "Christian Brothers remembers Spencer Webb: He loved life, and that's why this is so hard". The Sacramento Bee.

- ^ Dowling, Marcus K. (September 2, 2022). "Jon Pardi's 'Mr. Saturday Night' reveres honky-tonk heartbreak, 'old school entertainment'". The Tennessean.

- ^ "Dixon's Nick Watney becomes first PGA tour golfer to test positive for coronavirus". ABC10. Associated Press. June 19, 2020.

- ^ "Dave Ball Stats, Position, College, Transactions". Pro Football Archives.

- ^ "Espinoza Paz está de manteles largos". El Sol de Hermosillo (in Spanish). October 29, 2017.

- ^ Curley, Tim (February 26, 2021). "Sonoma musician profile: Joe Craven gets down in the dirt". Sonoma Index-Tribune.

- ^ "1992 Resolutions". City of Dixon, CA. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "Route 30". Fairfield and Suisun Transit. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "Welcome to Dixon Readi-Rde". City of Dixon, CA. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Meeting notice" (PDF). Solano Transportation Authority. January 8, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "Annual Comprehensive Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2022" (PDF). City of Dixon. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ Sestanovich, Nick (February 23, 2019). "Dixon braces for closure of Gymboree distribution center". Vacaville Reporter. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Paul, Bil (March 15, 2015). The Train Never Stops In Dixon (1st ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-5076-1791-5.

- ^ "Dixon Independent Voice". Dixon Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ "About". Dixon Independent Voice. Messenger Publishing Group.

- ^ "Dixon Tribune Closes". Dixon Independent Voice. February 2, 2024. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ Berg, Jerome (2013). The Early Shortwave Stations A Broadcasting History Through 1945. McFarland, Incorporated. ISBN 9780786474110. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Berg, Jerome (October 24, 2008). Broadcasting on the Short Waves 1945 to Today. McFarland. ISBN 9780786451982. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Proposed Closure of VOA Dixon Relay Station ID-79-42". GAO. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Stevenson, Merrill (June 30, 2016). "The Mystery of the Dixon Voice of America Relay Station". eham.net. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- ^ Paul, Bil (May 9, 2013). "Old AT&T Radio Station South of Dixon to Close Down". Patch. Retrieved August 23, 2022.