Transitional period of Sri Lanka

| History of Sri Lanka | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronicles | ||||||||||||||||

| Periods | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| By Topic | ||||||||||||||||

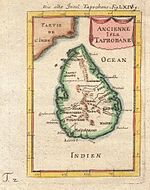

The Transitional period of Sri Lanka spans from the end of the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa, in 1232, to the start of the Kandyan period in 1597. The period is characterised by the succession of capitals that followed the fall of the Polonnaruwa Kingdom and the creation of the Jaffna kingdom and Crisis of the Sixteenth Century.

Overview

Periodization of Sri Lanka history:

| Dates | Period | Period | Span (years) | Subperiod | Span (years) | Main government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300,000 BP–~1000 BC | Prehistoric Sri Lanka | Stone Age | – | 300,000 | Unknown | |

| Bronze Age | – | |||||

| ~1000 BC–543 BC | Iron Age | – | 457 | |||

| 543 BC–437 BC | Ancient Sri Lanka | Pre-Anuradhapura | – | 106 | Monarchy | |

| 437 BC–463 AD | Anuradhapura | 1454 | Early Anuradhapura | 900 | ||

| 463–691 | Middle Anuradhapura | 228 | ||||

| 691–1017 | Post-classical Sri Lanka | Late Anuradhapura | 326 | |||

| 1017–1070 | Polonnaruwa | 215 | Chola conquest | 53 | ||

| 1055–1232 | 177 | |||||

| 1232–1341 | Transitional | 365 | Dambadeniya | 109 | ||

| 1341–1412 | Gampola | 71 | ||||

| 1412–1592 | Early Modern Sri Lanka | Kotte | 180 | |||

| 1592–1739 | Kandyan | 223 | 147 | |||

| 1739–1815 | Nayakkar | 76 | ||||

| 1815–1833 | Modern Sri Lanka | British Ceylon | 133 | Post-Kandyan | 18 | Colonial monarchy |

| 1833–1948 | 115 | |||||

| 1948–1972 | Contemporary Sri Lanka | Sri Lanka since 1948 | 76 | Dominion | 24 | Constitutional monarchy |

| 1972–present | Republic | 52 | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

Political history

Dambadeniya period (1232–1341)

Dambadeniya is an ancient capital of Sri Lanka. Four kings ruled from there, Vijayabâhu III (1220–1236), Parâkkamabâhu II (1236–1270), Vijayabâhu IV (1270–1272), and Bhuvanaikabâhu I (1272–1283). The first king to choose Dambadeniya as his capital was Vijayabâhu III. He was able to bring about unity among the sangha who had scattered due to the hostile invasion of the Kalinga magha. He also succeeded in holding a Buddhist convention in 1226 to bring about peace among the Buddhist clergy. Parâkkamabâhu II inherited the throne from Vijayabâhu III. He was considered a genius who was a great poet and prolific writer. Among the books he wrote are Kausilumina, which is considered a great piece of literature. Unifying the three kingdoms that existed within Sri Lanka at that point in time is regarded as his greatest achievement.

Vijayabâhu, as the eldest son of Parâkkamabâhu II, was crowned in 1270. He was well known for his modest behaviour and for his religious activities. He was killed in the second year of his reign by a minister called Miththa. After the demise of his elder brother Vijayabâhu, king Bhuvanaikabâhu I, as the next in line to the throne, shifted the capital to Yapahuwa for reasons of security. He followed his father's footsteps as a writer and continued with the religious activities started by his brother Vijayabâhu.

Jaffna Kingdom (1215–1624)

The Jaffna kingdom came into existence after the invasion of Magha, who is said to have been from Kalinga, in South India. It was a tribute-paying feudatory region of the Pandyan Empire in modern South India in 1250, but it later became independent with the fragmentation of the Pandyan control. For a brief period, in the early and middle 14th century, it was an ascendant power in the island of Sri Lanka when all regional kingdoms accepted subordination. However, the Jaffna kingdom came under the rule of the south on one occasion; in 1450, following the conquest by Parâkramabâhu VI's adopted son, Prince Sapumal. He ruled the North from 1450 to 1467.[1] It was freed of Kotte control in 1467. Its subsequent rulers directed their energies towards consolidating its economic potential by maximising revenue from pearls and elephant exports and land revenue. It was less feudal than most of other regional kingdoms in the island of the same period. During this period, important local Tamil literature was produced and Hindu temples were built, including an academy for language advancement.

Gampola period (1341–1412)

The capital was moved to Gampola by Buwanekabahu IV, he is said to be the son of Sawulu Vijayabāhu. During this time, a muslim traveller and geographer named Ibn Battuta came to Sri Lanka and wrote a book about it. The Gadaladeniya Viharaya is the main building made in the Gampola Kingdom period. The Lankatilaka Viharaya is also a main building built in Gampola.

Chinese admiral Zheng He and his naval expeditionary force landed at Galle, Sri Lanka in 1409 and got into battle with the local king Vira Alakesvara of Gampola. Zheng He captured King Vira Alakesvara and later released him.[2][3][4] Zheng He erected the Galle Trilingual Inscription, a stone tablet at Galle written in three languages (Chinese, Tamil, and Persian), to commemorate his visit.[5][6]

Kotte period (1412–1597)

By the Sixteenth century the population of the island was approximately 750,000, the majority, 400-450 thousand lived in the Kingdom of Kotte which was the largest and most powerful polity on the island.[7][8] Its boundaries reached from the Malvatu Oya in the North to the Valave River in the South, and from the central highlands to the western coast. The Kotte kings regarded themselves as Chakravartis (Emperors), laying claim to the whole island, after Parakramabahu VI, but actual power was limited to within their own boundaries.[9] Despite areas under its direct jurisdiction changing from time to time, Kotte held the island's lands where trade and agriculture were most developed. The Kotte kings were the largest land owners in the country, with much of the royal income coming from land revenue as opposed to trade. The Gabadāgam (Royal lands) accounted for more than three quarter of the annual royal income, and monetization of the economy in the littoral region began at least as far back as the fifteenth century.[8]

During this time the Portuguese entered into the internal politics of Sri Lanka. Largely by accident, first contact between the two nations was in 1505-06. But it was not until 1517-18 that the Portuguese sought to establish a fortified trading settlement in order to establish control over the island's Cinnamon trade, as opposed to territorial conquest.[10] The building of a fort, near Colombo, had to be given up due popular hostility that was fanned by Moorish traders, who had established themselves on the island and controlled a large portion of its external trade.[10] The Portuguese at no stage established dominance over the politics of South Asia, but sought to do so over its commerce by means of subjugation through naval power. Using their superior technology and sea power at points of weakness or divisions, the Portuguese would attain influence in greater proportions to their actual strength. Portuguese anxiety to establish a Bridgehead in Sri Lanka to control the island's Cinnamon trade drew them further into the politics of Sri Lanka.[11]

Kotte suffered from persistent succession disputes during this time. Though all were subordinate to the emperor of Kotte, brothers of the king would take the title Raja (king) and rule parts of the kingdom. This practice was possibly tolerated to humour princes who had some claim to the throne by giving them positions of responsibility, and the belief that having loyal relatives in outlying districts afforded some security to the king. However this political structure inevitably led to its own weakening in the long run, as those princes, who could, virtually administered the areas they claimed as autonomous principalities.[12]

Crisis of the Sixteenth Century (1521–1597)

In 1521 the Vijayabā Kollaya was one such and the most eventful of succession disputes in the kingdom and would trigger the most chaotic period in the history of Sri Lanka. Vijayabāhu VI, who had four sons by two wives, sought to select his youngest son for the succession of the kingdom. In reaction the three older brothers assassinated their father, with the assistance of the Kandyan ruler, and divided the kingdom among themselves. With this partition the fragmentation of the Sri Lankan polity seemed well beyond the capacity of any statesman to repair.[12] The Kandyan ruler took advantage of the situation in a cynical and shrewd move to aggravate the political instability as an opportunity to assert their independence from the control of Kotte. Kanday ruler Jayavira Bandara (1511–52) readily aided the three princes against their father, and it was clear the decline of the Kingdom of Kotte was necessary for the rise of the Kingdom of Kandy.[10]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Holt 1991, p. 304.

- ^ Wade 2005.

- ^ Voyages of Zheng He 1405–1433 2015.

- ^ Ming Voyages 2015.

- ^ The trilingual inscription of Admiral Zheng 2015.

- ^ Zheng He 2015.

- ^ Pieris 2011.

- ^ a b de Silva 2005, p. 142.

- ^ de Silva 2005, p. 143.

- ^ a b c de Silva 2005, p. 145.

- ^ de Silva 2005, p. 147.

- ^ a b de Silva 2005, p. 144.

Bibliography

- Books

- Holt, John (1991). Buddha in the Crown: Avalokiteśvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195064186.

- de Silva, K. M. (2005). A History of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications. ISBN 9789558095928.

- Web

- "The trilingual inscription of Admiral Zheng He". lankalibrary forum. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- "Zheng He". world heritage site. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- "Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource, Singapore: Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press". Translated by Wade, Geoff. National University of Singapore. 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- News

- Pieris, Kamalika (4 November 2011). "Land tenure in 16th Century Sri Lanka". The Island. Retrieved 23 September 2019.