Creevelea Abbey

Mainistir na Craoibhe Léithe | |

| |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Creevlea Abbey, Creebelea Abbey, Craobhliath, Crowlekale, Crueleach, Carrag Patrice, Petra Patricii, Druim-da-ethair, Baile-ui-ruairc, Ballegruaircy, Cuivelleagh, Killanummery.[1] |

| Order | Third Order of Saint Francis (Order of Penance) |

| Established | 1508 |

| Disestablished | 1837 |

| Diocese | Kilmore |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Eóghan Ó Ruairc |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Inactive |

| Site | |

| Location | Creevelea, Dromahair, County Leitrim |

| Coordinates | 54°13′53″N 8°18′35″W / 54.231291°N 8.309791°W |

| Visible remains | church walls, one or two unstable stairs, the perimeter structure. |

| Public access | yes, as a burial site |

| Official name | Creevelea Abbey |

| Reference no. | 69[2] |

Creevelea Abbey is an early 16th-century Franciscan friary and National Monument located in Dromahair, County Leitrim, Ireland.[3] Although in ruins, Creevelea Abbey is still in use as a grave yard.

Location

Creevelea Abbey is located west of Dromahair, on the west bank of the Bonet River.[4][5]

History

Creevelea Friary was founded in 1508 by Eóghan O'Rourke, Lord of West Bréifne, and his wife Margaret O'Brian, daughter of a King of Thomond, as a daughter foundation of Donegal Abbey. The friary was accidentally burned in 1536, but was rebuilt by Brian Ballach O'Rourke. In 1590, Richard Bingham stabled his horses at Creevelea during his pursuit of Brian O'Rourke, who had sheltered survivors of the Spanish Armada. Dissolved c. 1598.[6]

Sir Tadhg O'Rourke (d. 1605), last King of West Bréifne and Thaddeus Francis O'Rourke (d. 1735), Bishop of Killala are buried here. Another house was built for the friars in 1618 and Creevelea was reoccupied by friars in 1642. The Franciscans were again driven out by the New Model Army during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in the 1650s.[7][8] After the Restoration, the Franciscans returned and continued to live in thatched cabins nearby. During the early 18th-century, pioneering antiquarian and Celticist Charles O'Conor of Bellanagare, a descendant of the local Gaelic nobility of Ireland, received his early education at a hedge school taught by the surviving Friars.[9] Although it was once widely assumed that Gaelic Ireland completely missed Renaissance humanism and the revival of interest in the Classics, O'Conor later recalled that he was taught the Latin language using the grammar of Corderius, and the writings of Ovid, Suetonius, and Erasmus. O'Conor recalled that he was also taught the playing of the Celtic harp, as well as fencing and dancing.[10] According to Tony Nugent, the surviving Franciscans also used a Megalithic tomb site in the nearby townland of Sranagarvanagh, or in Connaught Irish Srath na nGarbhánach, as a Mass rock, also during the 18th-century. A walking track has since been built to the site under a Fás scheme.[11] The Abbey Church remained in use as living quarters until 1837.

Buildings

The remains consist of the church (nave, chancel, transept and choir), chapter house, cloister and domestic buildings. The bell-tower was converted to living quarters in the 17th century. At one point in its history the church was covered with a thatched roof. Carved in the cloister is an image of Saint Francis of Assisi preaching to birds.[12][13] The site also contained, as of 1870, many stone monuments to the local members of the Gaelic nobility of Ireland who lie buried there.[14]

People

- Patrick O'Hely (c.1543 - 1579), Franciscan Friar who did his novitiate and final vows at Creevelea Abbey. After returning to Ireland following his consecration abroad as Bishop of Mayo, he was captured, tortured, and hanged outside the walls of Kilmallock as part of the Elizabethan era religious persecution of the Catholic Church in Ireland. Beatified in 1992 by Pope John Paul II as one of the 24 officially recognized Irish Catholic Martyrs. His feast day is June 20.

Archaeological Preservation

The site is preserved as a national monument.[15]

- Tower

- Window with tracery

- Cloister

- Creevela Abbey 1791

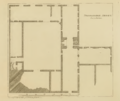

- Floorplan 1791

References and Notes

Notes

Citations

- ^ Sunflower Guides 2004, pp. 10.

- ^ "National Monuments of County Leitrim in State Care" (PDF). heritageireland.ie. National Monument Service. p. 1. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ TripAdvisor.

- ^ Brewer 2008, pp. 365.

- ^ Day 2006, pp. 334.

- ^ Charles Patrick Meehan (1870). The rise and fall of the Irish Franciscan monasteries, and Memoirs of the Irish hierarchy in the seventeenth century. J. Duffy. pp. 77–81.

- ^ megalithicireland.

- ^ Higgins.

- ^ Charles Patrick Meehan (1870). The rise and fall of the Irish Franciscan monasteries, and Memoirs of the Irish hierarchy in the seventeenth century. J. Duffy. pp. 77–81.

- ^ Charles O'Conor, Dictionary of Irish Biography

- ^ Nugent, Tony (2013). Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland. Liffey Press. ISBN 9781908308474. pp. 175-176.

- ^ The Sligo Town Website.

- ^ Manorhamilton.ie 2012.

- ^ Charles Patrick Meehan (1870). The rise and fall of the Irish Franciscan monasteries, and Memoirs of the Irish hierarchy in the seventeenth century. J. Duffy. p. 81.

- ^ National Monuments Service 2009, pp. 1.

Primary sources

- Sunflower Guides (1 March 2004). Ireland. Hunter Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9781856912433 – via Google Books.

- TripAdvisor. "Creevelea Friary (Leitrim, Ireland): Top Tips Before You Go - TripAdvisor". TripAdvisor.

- Brewer, Stephen (29 September 2008). Attraction on Lough Gill. Vol. The Unofficial Guide to Ireland. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470285688 – via Google Books.

- Day, Catharina (1 January 2006). The province of Connacht, Around Drumahair. Vol. Ireland. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781860113277. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- megalithicireland. "Creevelea Abbey". megalithicireland.com.

- Higgins, Gerard. "Creevelea Abbey". sligotours.com.

- "Creevelea Abbey in Dromahair". The Sligo Town Website.

- Manorhamilton.ie (2012). "Creevelea Abbey". manorhamilton.ie. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

Secondary sources

- National Monuments Service (2009). Leitrim (PDF) (Report). Vol. National Monuments in State Care: Ownership & Guardianship. Environment, Heritage and Local Government.