Coldbath Fields riot

The Coldbath Fields riot took place in Clerkenwell, London, on 13 May 1833. The riot occurred as the Metropolitan Police attempted to break up a meeting of the National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC). Figures for the number of police present at the varied between 70 and 600 officers; figures for members of the public who attended varied between 300 and 6,000. Both Commissioners of Police of the Metropolis, Sir Charles Rowan and Sir Richard Mayne, were present and two British Army officers stood by to summon military reinforcements if needed. It is disputed which side started the violence, but Rowan led a number of baton charges that dispersed the crowd, and arrested the NUWC leaders. The crowd were pursued into side streets and a number were trapped in Calthorpe Street. Three police officers were stabbed and one, Constable Robert Culley, was killed. There were few serious injuries inflicted on members of the public.

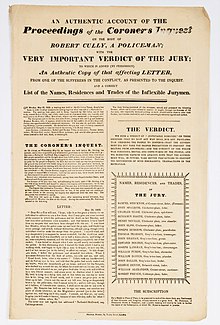

A coroner's jury ruled Culley's death was justifiable homicide as the police had failed to read the Riot Act and been heavy handed in their dispersal of the crowd. This verdict was overturned by a government appeal to the High Court of Justice, but no-one was brought to trial for Culley's murder. George Fursey was charged with the wounding of the other two officers, but was acquitted by a jury at the Old Bailey. The coroner's jury, who had been feted by the Radicals, complained to the House of Commons. A select committee investigated the riot and largely exonerated the police, although it did note that Melbourne's declaration of the meeting as illegal was invalid as the document had not been signed.

Background

The Metropolitan Police had been founded in 1829, replacing a patchwork system of local night watchmen and parish constables who had struggled to maintain order in a rapidly-growing London.[1] Most of the public were highly suspicious of the police, viewing them as an extension of the arm of the state and out of line with traditional English libertarian values.[1][2] The reputation of the Metropolitan Police was affected by discipline issues and a high turnover of constables;[nb 1] Some publications derided the police as "raw lobsters" and "blue devils".[4][nb 2] By August 1830 the first two officers had been killed on duty.[6][7]

The English Radicals regarded the establishment of the police as an infringement of civil liberties, akin to the militarised gendarmerie that existed in Napoleonic France. The British military had previously been used to break up public demonstrations. The Peterloo Massacre of 1819, in which 18 civilians were killed by the British military intervening in a political demonstration, was in recent memory.[1]

The National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC), a political organisation associated with the Southwark-based Rotunda radicals, called a meeting to be held on open ground behind Coldbath Fields Prison on 13 May 1833.[8][9] The aim of the meeting was to call for the extension of the electoral franchise to a wider section of the male public beyond the relatively wealthy.[10] The NUWC had been disappointed by the Reform Act 1832 which had led to a small increase in the franchise.[9]

The NUWC's secretary, John Russell, promoted the meeting in The Poor Man's Guardian and The Working Man's Friend, as well as with numerous handbills and posters in the weeks preceding it.[9][11] Some of the handbills requested that attendees arm themselves.[6] The Home Secretary Lord Melbourne declared the meeting illegal and Prime Minister Lord Grey ordered the Metropolitan Police to arrest the ring leaders should the meeting take place.[11][12] Melbourne ordered the joint Commissioners of Police of the Metropolis, Sir Charles Rowan and Sir Richard Mayne, to break up the meeting. The commissioners queried the legal basis for Melbourne's order and met with him to discuss it.[9] The police posted notices warning that the meeting was illegal and would be dispersed if it went ahead.[11]

Riot

In the lead-up to the riot the police had infiltrated meetings of the NUWC and used the information gained to develop their tactics, but the police in general had little experience in dealing with public demonstrations.[9][11] The occasion was the first major confrontation between the Metropolitan Police and a crowd.[12]

By mid-day some 300 members of the public had assembled for the meeting.[9] It was not until almost 3 pm, around an hour later than publicised, that NUWC leaders began to address the crowd from the backs of open-topped wagons.[11][13][14] By this time there may have been up to 4,000 members of the public at the meeting and up to 600 officers.[nb 3] Besides a contingent of around 200 police from A division (Whitehall) officers had been drafted in from other areas including more than 110 men from F Division (Covent Garden) sent from Bow Street police station and commanded by Superintendent Joseph Sadler Thomas.[14][17] Both Metropolitan Police commissioners were present at the scene as well as two officers from the British Army's 1st Regiment of Life Guards, dressed in civilian clothing but ready to summon a detachment of their unit if needed to assist the police.[9]

The police had orders to wait until the speakers began, before they broke up the crowd, so that the event could be confirmed positively as a NUWC meeting.[11][13] Contemporary reports disagree on whether the police drew their batons before or after being attacked by the crowd.[9] The police reported that the event was attended by "the lowest classes" who had armed themselves with knives, improvised lances, brickbats and cudgels.[6][11] By one contemporary press report many of the police were drunk.[9][11] It is known that Rowan led several baton charges against the crowd who threw stones at the police.[12] Within five minutes of taking action the police had dispersed the crowd and arrested the leaders of the meeting, including James Lee, one of two men who addressed the assembly.[11][14] The police made 21 arrests and a correspondent for the Times estimated that 50 civilians had been wounded.[14]

About 200 of the police force, of the A division, followed by as many of the others, marched up to the railings, with their truncheons, ready for action. The mob gave a little way ... The scene that followed was truly dreadful. The police furiously attacked the multitude with their staves, felling every person indiscriminately before them; even the females did not escape the blows from their batons – men and boys were lying in every direction weltering in their blood and calling for mercy ... A large space of ground within our view was strewed with the wounded, besides others who were less injured who were able to crawl to a surgeon's.

— "The Meeting of the National Union". The Times. No. 15164. 14 May 1833.

The crowd dispersed into nearby streets where the police's actions left some trapped.[11][15] A portion of the crowd on Calthorpe Street attempted to fight their way clear.[13] Around this time three of the police officers were stabbed.[11] Sergeant John Brooks and Constable Henry Redwood were wounded while trying to take a flag from a demonstrator.[9][18] In unknown circumstances Constable Robert Culley was stabbed in the chest. He staggered into the yard of the Calthorpe Arms public house where he collapsed and died.[6][18] Culley had been one of the first men to join the Metropolitan Police, carrying out his first patrol on 21 September 1829, at the age of 23.[13][18] His wife was carrying their first child when he was killed.[18]

Aftermath

Culley's death was subject to a coroner's inquest with a 15-man jury. This met, under Coronor for West Middlesex Thomas Stirling, in the upstairs room of the Calthorpe Arms, in the yard of which Culley had died.[18] The jury were local shopkeepers and household heads, not considered to be Radicals.[13]

At the time magistrates, judges and juries were often biased against the police and the Culley inquest jury is considered to be one example of this.[19] The jury did not accept the evidence presented by the police and ruled that the "conduct of the police was ferocious, brutal, and unprovoked by the people."[9][18] The jury returned a verdict of justifiable homicide on 21 May on the basis that the Riot Act had not been read or the crowd asked to disperse.[18]

This verdict was challenged by the Solicitor General for England and Wales Sir John Campbell and overturned by the King's Bench Division of the High Court of Justice on 30 May, being replaced by a verdict of "wilful murder by a person or persons unknown".[6][18] Despite the new verdict there was no police investigation into Culley's death beyond a police surgeon determining that the knife used to stab Brooks and Redwood had not been used in the killing of Culley.[18] George Fursey was charged with stabbing the other two officers but was acquitted by a jury in a criminal trial at the Old Bailey on 8 July 1833.[9] The British government, for the first time, paid £200 compensation to Culley's widow.[20]

The original jury wrote to parliament to protest the overturning of their verdict, alleging that the King's Bench judgment had cast a slur on their characters.[18] They were supported by William Cobbett, a Radical Member of Parliament (MP), who was a notable critic of the police and alleged that they had used swords and guns, though there was no evidence of this in any injuries suffered by the crowd.[6] In response a House of Commons select committee was established to examine the conduct of the police during the riot. It largely exonerated the police, noting that no "dangerous wound or permanent injury" had been suffered by members of the crowd.[18] It heard from a Hackney magistrate that the police were "the most efficient and least offensive system for the protection of person and property that was ever devised".[21] During the committee's sessions it was found that Melbourne had not signed the public notice outlawing the Coldbath Fields meeting and that meant the notice had no legal effect. Melbourne also told the committee that he had only wanted the ringleaders arrested and not for the crowd to be dispersed. Mayne disproved this as he had kept notes from the commissioners' meeting with Melbourne.[22]

The coroner's jury were feted by the public for their original verdict. Within days of their discharge their foreman, Samuel Stockton, was presented with a set of pewter medallions for all the jury members. These were engraved with the message "In honour of the men who nobly withstood the dictation of the coroner; independent, and conscientious, discharge of their duty; promoted a continued reliance upon the laws under the protection of a British jury".[9] They were cheered in the streets and rewarded, in June, by the Milton Street Committee, a group of wealthy Radicals, with a boat trip along the Thames to Twickenham on the steamer Endeavour.[9] Upon arrival they were met with a cheering crowd and honoured with a gun salute.[13] A year after the riot the Milton Street Committee held a banquet at the Highbury Barn Tavern in honour of the jury. It was hosted by Radical MP Sir Samuel Whalley and attended by 150 people, including at least one other MP. Each juror was presented with a silver cup, after a toast to "The people, the only source of legitimate power"[9][18] - one each of the cups is now on display in the Metropolitan Police's Crime Museum and Police Museum.[23] Stockton continued to be feted into the 1860s, with a dinner being held at the Benevolent Institution just off Haverstock Hill and a 20-guinea clock presented to him.[9]

Police Superintendent Thomas came in for criticism for "high-handedness" during the riot. He was suspended shortly afterwards over a dispute with a pub landlord about a licence application.[8] Thomas left the Metropolitan Police later in 1833 to become deputy constable of Manchester City Police.[24] Grey's Whig government came in for criticism in the Radical press for their actions in the lead-up to the riot. The Radicals accused the Whigs, who positioned themselves as a liberal party, of committing excesses of power comparable to those committed by the Tories at Peterloo.[25]

Legacy

According to policing historian R. I. Mawby the killing of Culley may have caused an increase in public sympathy for the police, which led to their general acceptance of the institution.[26] The riot was the only legal precedent for the police in dealing with public meetings until the 1870s.[22] The police response to riots generally improved and there were few occasions when the military had to be called in.[21] The Metropolitan Police Act 1839 reformed London's police force and increased their numbers.[1]

Culley is one of only three Metropolitan Police officers whose deaths have been caused by rioting, the others being Station Sergeant Thomas Green in the 1919 Epsom riot and Police Constable Keith Blakelock in the 1985 Broadwater Farm riot.[18] No-one was ever convicted of any of the deaths.[27]

Notes

- ^ Turnover of officers in the early Metropolitan Police was over 80% in its first 16 months, with 80% of those leaving being dismissed for drunkenness on duty.[3] It improved a little afterwards but of the 2,800 officers in position in May 1830, only 562 remained in post four years later.[1]

- ^ The "blue lobsters" name came from the Homarus gammarus which was blue when raw and red when cooked. Suggesting that the blue-coated police tended to behave like the red-coated army when threatened.[5]

- ^ Social historian Sarah Wise (2012) gives only 300 members of the crowd while historian of Chartism David Goodway (2002) gives 3-4,000.[8][15] Crime historian Francis Dodsworth (2019) states that there were 70 police officers in attendance while Roy Ingleton, who writes on the history of police forces, gives 600, who he states were outnumbered 10-1, in a 2020 work.[11][6] Robert Gould and Michael Waldren, in a history of armed police in London (1986), state 70 officers were at the meeting, with a further 500 officers stationed in a nearby stables.[16]

References

- ^ a b c d e Moult, Tom (15 March 2012). "The Metropolitan Police in Nineteenth-Century London: A Brief Introduction". New Histories. University of Sheffield. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Emsley, Clive (1986). "Detection and Prevention: The Old English Police and the New 1750-1900". Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung (37): 69–70. ISSN 0172-6404. JSTOR 20755018.

- ^ Smith, Graham (25 August 2020). On the Wrong Side of The Law: Complaints Against Metropolitan Police, 1829-1964. Springer Nature. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-030-48222-0.

- ^ Gould, Robert W.; Waldren, Michael J. (1986). London's Armed Police: 1829 to the Present. London: Arms and Armour PRess. p. 11. ISBN 0-85368-880-X.

- ^ "'Reviewing the blue devils, alias the raw lobsters, alias the bludgeon men' from The Political Drama". British Library. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ingleton, Roy (15 July 2020). Arming the British Police: The Great Debate. Routledge. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-1-000-14411-6.

- ^ Gould, Robert W.; Waldren, Michael J. (1986). London's Armed Police: 1829 to the Present. London: Arms and Armour PRess. p. 12. ISBN 0-85368-880-X.

- ^ a b c Wise, Sarah (31 December 2012). The Italian Boy: Murder and Grave-Robbery in 1830s London. Random House. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-4481-6224-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Public Order: Heavy-Handed Policing: The Killing of Constable Culley". International Centre for the History of Crime, Policing and Justice. Open University. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "Papers relating to the National Union of the Working Classes". British History Online.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dodsworth, Francis (7 May 2019). The Security Society: History, Patriarchy, Protection. Springer. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-137-43383-1.

- ^ a b c Roth, Mitchel P. (2001). Historical Dictionary of Law Enforcement. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-313-30560-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Awcock, Hannah (13 May 2017). "On This Day: The Coldbath Fields Riot, 13th May 1833". Turbulent Isles. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The Meeting of the National Union". The Times. No. 15164. 14 May 1833.

- ^ a b Goodway, David (10 October 2002). London Chartism 1838-1848. Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-521-89364-0.

- ^ Gould, Robert W.; Waldren, Michael J. (1986). London's Armed Police: 1829 to the Present. London: Arms and Armour Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-85368-880-X.

- ^ The Gauntlet. Greenwood Reprint Corporation. 1970. p. 250.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Moore, Tony (27 May 2015). The Killing of Constable Keith Blakelock: The Broadwater Farm Riot. Waterside Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-909976-20-7.

- ^ Heron, F. E. (1969). A Brief History of the Metropolitan Police. p. 15.

- ^ Gould, Robert W.; Waldren, Michael J. (1986). London's Armed Police: 1829 to the Present. London: Arms and Armour PRess. p. 14. ISBN 0-85368-880-X.

- ^ a b Porter, Bernard (29 January 2016). Plots and Paranoia: A History of Political Espionage in Britain 1790-1988. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-317-35636-3.

- ^ a b Keller, Lisa (2009). Triumph of Order: Democracy & Public Space in New York and London. Columbia University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-231-14672-2.

- ^ Alan Moss and Keith Skinner, Scotland Yard's History of Crime in 100 Objects (The History Press Ltd, 2015), pages 20-23

- ^ "Joseph Sadler Thomas". British Museum. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ Lang, Sean (15 July 2005). Parliamentary Reform 1785-1928. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-134-67015-4.

- ^ Mawby, R. I. (15 April 2013). Policing Across the World: Issues for the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-135-36458-8.

- ^ Moore, Tony (27 May 2015). The Killing of Constable Keith Blakelock: The Broadwater Farm Riot. Waterside Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-909976-20-7.

External links

- "Inquest On Culley". Hansard. UK Parliament. House of Commons, Thursday 13 June 1833.