Clive Spash

Clive L. Spash is an ecological economist. He currently holds the Chair of Public Policy and Governance at Vienna University of Economics and Business, appointed in 2010.[1] He is also Editor-in-Chief of the academic journal Environmental Values.[2]

Career

Spash studied economics at the University of Stirling gaining a Bachelor of Arts with Honours. His dissertation was entitled "Sulphur Emission and Deposition in Europe: A Problem of Transfrontier Pollution". He went on to study for a master's degree in interdisciplinary studies at the University of British Columbia with a thesis entitled "Measuring the Tangible Benefits of Environmental Improvement: An Economic Appraisal of Regional Crop Damages due to Ozone. He then completed a Ph.D. with Distinction in Economics at the University of Wyoming in 1993, specialising in Resource and Environmental Economics and Public Finance. His dissertation, "Intergenerational Transfers and Long-Term Environmental Damages: Compensation of Future Generations for Global Climate Change due to the Greenhouse Effect", was awarded the University of Wyoming Outstanding Dissertation in the Social Sciences, 1993.[3]

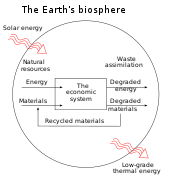

| Part of a series on |

| Ecological economics |

|---|

|

Spash was elected vice-president of the European Society for Ecological Economics (ESEE) by the delegates at the inaugural meeting of the society held at Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France in 1996. He was elected to a second term by ESEE members at the Society General Meeting in Geneva, Switzerland in 1998. He then served two terms as ESEE President, 2000–2006, elected by postal ballot of the membership. During this time he helped write new democratic constitutions for both the ESEE and ISEE, established the ESEE Newsletter with Ben Davies as editor, set-up the societies committee structure and organised European conferences.[4]

From 1996 until 2001 he was a lecturer at the Department of Land Economy at the University of Cambridge and director of the research institute Cambridge Research for the Environment (CRE). He then moved to the University of Aberdeen where he held the Research Chair in Environmental and Rural Economics and was Head of the Socio-Economic Research Programme (SERP) at the Macaulay Institute of Land Use Research.

In 2006 Spash was appointed as Chief Executive Officers’ Science Leader at the CSIRO, Australia's federal government agency responsible for scientific research. After finishing a critical paper about emissions trading - which had already passed the peer review process - the agency intervened and pushed for substantial changes.[5] The behaviour of CSIRO led to controversial debates within the scientific community and Nature reported extensively on the conflict.[6][7] In the course of the controversy, Spash left the agency at the end of 2009.[8]

Key Scientific Contributions

Spash was one of the earliest economists to pay attention to human induced climate change, pioneering an alternative economics of the environment. He followed some aspects of the work of his doctoral supervisor, Ralph C. d’Arge, in exploring its economic and ethical implications with respect to intergenerational equity and justice.[9][10] He built from this into issues of compensation for harm across generations and ethical limitations of the economic approach.[11][12] Such topics appeared in his book Greenhouse Economics,[13] which covers the history, science, economics, ethics and public policy relating to climate change. That work was also path-breaking in its highly critical reflections on mainstream economic approaches that use social cost-benefit analysis and of the work of William Nordhaus.[14][15][16][17] In 2018 Nordhaus received the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences, or the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel for this same work, which has since been strongly criticised by others .[18]

Spash’s work has developed in devoting attention to the social economic consequences of a broad range of environmental problems (e.g. acidic deposition, tropospheric or ground level ozone, greenhouse gases, conservation, ecosystem and species protection). His work on the economics of biodiversity was also amongst the first in the field. His work on ethical considerations in economics has included intra- and inter- generational justice as well as non-humans and their treatment in economics. Behavioural concerns have been reflected in a series of articles on social psychology (sociology). He has also importantly incorporated a history of thought and philosophy of science perspective in his reimagining of the ontological and epistemological foundations of economics as a field. This has particularly stressed the incorporation of the social dimension as inextricably linked to ecological economic as a realist science. This approach he terms social ecological economics.

Critiques of Mainstream Economics

Spash has developed extensive critiques of mainstream economic approaches to the environment. These cover its limited ethical foundations,[19][20] its failure to address manifest problems with its own methods,[21] problems with preference theory,[22][23][24][25][26] the social problems of advocating economic growth in macroeconomics,[27][28][29] the failings of consumer choice theory,[30][31] and mainstream economists' general lack of realism [32] .[33]

Environmental Values

Spash has worked extensively on ecosystem valuation and was Editor-in-Chief of the journal "Environmental Values" (2006-2021). His early research explored the application of cost-benefit analysis to environmental change and especially air pollution damages.[34] This research moved from work on acidic deposition to tropospheric zone to greenhouse gases and climate change, as evident in his dissertations and thesis. He co-authored an influential textbook on environmental cost-benefit analysis,[35] but his work was increasingly critical of the approach. The approach to intergenerational ethics that is reduced down to a discussion over discount rates is exposed as obscuring the presence of implicit value judgements while claiming objectivity.[36] This approach's fallacious reduction of strong uncertainty (social indeterminacy and ignorance) to weak uncertainty (probabilistic risk) is exposed in his book "Greenhouse Economics".[37]

Environmental Cost-Benefit Analysis, Contingent and Deliberative Valuation

Spash’s work in the area of environmental cost-benefit analysis (e.g. Hanley and Spash[38]) developed into the exploration of social psychology and motivations for environmental values.[39] He employed contingent valuation to conduct empirical research in innovative ways that included ethical motives as well as attitudes and norms.[40][41][42][43][44] At the same time his work revealed fundamental failures of contingent valuation research [45] and its employment for public policy by environmental economists.[46] He moved into exploring the possibilities for alternative deliberative approaches,[47][48] their combination with monetary valuation,[49][50] and the implications of deliberation for economic value theory.[51] Spash cited the term deliberative monetary valuation (DMV) to summarise a set of approaches being employed to combine individualistic willingness to pay (WTP) assessments of the valuation of environmental damage and preservation with group approaches and various related methods. He importantly noted that social values are qualitatively distinct from the aggregate of individual values, highlighting an overlooked weakness in results gathered from DMV studies;[52] that findings of DMV research elucidate the complexity of human value systems and preferences, which goes uncaptured by common economic conceptualisations and by the method itself;[53] and that “exclusion and predefinition of values” inherent in commonly practiced DMV methods constrain or prevent the expression of value pluralism.[54] An alternative “discourse based approach” [55] is proposed that address these methodological concerns (see also O'Hara 1996,[56] 2001[57]), and this involves reconceptualising DMV 'as a mutual agreement resulting from an interactive process involving the contestation of discourses'.[58]

Climate Economics

His climate economics involves realist and ethical critiques of mainstream economics and has targeted the work of David Pearce (economist), William Nordhaus, Richard Tol and others.[59][60] He has deconstructed the work of Lord David Stern in both his Stern Review[61] [62] and under the New Climate Economy collective.[63] His critiques of the economics of climate change include its intergenerational ethics,[64][65] its approach to uncertain futures involving ignorance and indeterminacy,[66] and social cost-benefit approaches to decision-making [67] .[68][69] He has also criticized the mainstream economic approach to policy encapsulated under carbon emission trading, also known as cap-and-trade.[70] His work in this area was censored by the government in Australia but finally released after a Senate vote defeated the government.[71] Carbon trading is seen by Spash as failing both in theory and practice and in compulsory as well as voluntary forms.[72][73][74] He has argued the Paris Agreement is a failure to address reality and not a great success on which to build.[75][76] Spash has concluded in favour of rights-based approaches and regulation rather than utilitarianism and carbon trading.[77][78]

Biodiversity Economics

Spash also linked issues in valuation to ethical positions and refusals to trade-off species and ecosystem loss, and contrasted rights-based ethics with utilitarianism in conservation.[79][80] He was one of the first economists to work on biodiversity valuation in economics.[81] His work here developed approaches to empirically investigate ethically motivated refusals to trade-off species and ecosystems for money as expressed by the occurrence of lexicographic preferences[82][83][84] .[85] This work on biodiversity economics also led to criticism of preference utilitarianism [86] and the spread of mainstream economics into ecology and conservation biology.[87][88] In the early 1990s Spash designed a survey conducted in Scotland on forestry to explore the valuation of biodiversity and the occurrence of protesting and refusals to make the trade-offs that economists had previously assumed were rational.[89] He developed this further in studies of wetland re-creation in East Anglia[90] and coral reef improvement in Curaçao.[91] Willingness-to-pay responses from contingent valuation were found to be charitable contributions for many respondents, and not trade prices as economists assumed.[92] The work expanded into attitudinal and social norm research using measures from social psychology and questioning various claims made about the results from contingent valuation.[93] Related work questioned prominent environmental attitudinal scales used by social psychologists [94] and aspects of work by Daniel Kahneman on valuation.[95] When "Biodiversity Economics: The Dasgupta Review" appeared in 2021, advocating natural capital, Spash produced critical deconstructions of the report.[96][97]

Social Ecological Economics

Spash’s research in the 2000s became directed towards the development of a paradigm shift to a social ecological economics.[98][99][100] He highlighted the need for ecological economics to have firm foundations in philosophy of science and to link ontology to epistemology rather than follow an eclectic pluralism in economics.[101] His key conclusions here support the need for integration of social, ecological and economic knowledge,[102] and combining heterodox schools of thought in a structured methodological pluralism.[103][104] This is seen as a way forward that emphasises “the structural aspects of economies as emergent from and dependent upon the structure and functioning of both society and ecology“.[105] This conceptualisation rejects reductionist approaches and builds on interdisciplinarity (over mono- or multi-disciplinarity), while incorporating value incommensurability and value pluralism.[106] His research recommends the philosophy of science of critical realism.[107] Spash’s research has highlighted problems arising from the conceptualisation of ecological economics as a simple combination of two disciplines (i.e. ecology and economics) that otherwise remain divorced from each other and unreformed by their interaction.[108] He has developed this critique into an exploration of the divisions within ecological economics, and more generally the environmental movement, by defining three categories: social ecological economists, new environmental pragmatists and new resource economists.[109][110][111][112] His work includes some empirical evidence on these categories.[113] Moving beyond a simple division within the field, the social ecological economics category has become advocated as a new paradigm.[114] Spash sees social ecological economics as the way forward for the field of economics in general.[115][116]

Publications (inter alia)

- Clive L. Spash (ed.) (2017). Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Clive L. Spash and Karin Dobernig (2017). Theories of (Un)sustainable Consumption. In Spash, Clive L. (ed.) Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society (pp. 203–213). Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Clive L. Spash and Clemens Gattringer (2017). The Ethical Failures of Climate Economics. In Adrian Walsh, Sade Hormio and Duncan Purves (eds.) The Ethical Underpinnings of Climate Economics (pp. 162–182). Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Clive L. Spash (2016). This changes nothing: The Paris Agreement to ignore reality. Globalizations 13 no.6: 928–933.

- Clive L. Spash (2010). The Brave New World of Carbon Trading. New Political Economy, 15, no. 2: 169–195.

- Clive L. Spash (2010) Censoring science in research officially. Environmental Values 19 no. 2: 141–146.

- Clive L. Spash (2002). Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics. London: Routledge.

- Martin O’Connor and Clive L. Spash (1999). Valuation and the Environment: Theory, Methods and Practice. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Clive L. Spash (1995). The political economy of nature. Review of Political Economy, 7 no .3: 279–293.

- Clive L. Spash and Ian A. Simpson (1994). Utilitarian and rights-based alternatives for protecting sites of special scientific interest. Journal of Agricultural Economics. 45 no.1: 15-26

References

- ^ "SPASH Clive, PhD". WU (Vienna University of Economics and Business). Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- ^ "Environmental Values".

- ^ "Curriculum Vitae". Clive L. Spash. 2015-04-26. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- ^ "Curriculum Vitae". Clive L. Spash. 2015-04-26. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- ^ CORRESPONDENT, Dan Harrison EDUCATION (2009-12-03). "Scientist quits CSIRO amid censorship claims". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Pincock, Stephen (2009-11-06). "Australian agency denies gagging researchers". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.1068. ISSN 1744-7933.

- ^ Pincock, Stephen (2009-11-13). "Australian agency moves to calm climate row". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.1083. ISSN 1744-7933.

- ^ Pincock, Stephen (2009-12-04). "Researcher quits over science agency interference". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.1126. ISSN 1744-7933.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; d'Arge, R. C. (1989). "The greenhouse effect and intergenerational transfers". Energy Policy. 17 (2): 88–95. Bibcode:1989EnPol..17...88S. doi:10.1016/0301-4215(89)90086-4.

- ^ d'Arge, R. C.; Spash, C. L. (1991), "Economic strategies for mitigating the impacts of climate change on future generations", in Costanza, R. (ed.), Ecological Economics: The Science and Management of Sustainability, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 367–383, doi:10.2307/1243998, JSTOR 1243998

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1994a). "Double CO2 and beyond: Benefits, costs and compensation". Ecological Economics. 10 (1): 27–36. Bibcode:1994EcoEc..10...27S. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(94)90034-5.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1993a). Intergenerational Transfers and Long Term Environmental Damages: Compensation of Future Generations for Global Climate Change due to the Greenhouse Effect (PhD). University of Wyoming Department of Economics.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002a). Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics. London: Routledge.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002b), "Loading the dice?: Values, opinions and ethics", Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics, London: Routledge, pp. 184–200

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002b), "Calculating the Costs and Benefits of Greenhouse Gas Control", Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics, London: Routledge, pp. 184–200

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2007d). "Understanding climate change: Need for new economic thought". Economic and Political Weekly (February): 483–490.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008d). "The economics of avoiding action on climate change". Adbusters. 16 (1).

- ^ Keen, S. (2021). "The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change". Globalizations. 18 (7): 1149–1177. Bibcode:2021Glob...18.1149K. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.1807856. S2CID 225300874.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1993b). "Economics, ethics, and long-term environmental damages". Environmental Ethics. 15 (2): 117–132. doi:10.5840/enviroethics199315227.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1997a). "Ethics and environmental attitudes with implications for economic valuation". Journal of Environmental Management. 50 (4): 403–416. Bibcode:1997JEnvM..50..403S. doi:10.1006/jema.1997.0017.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008a). "Contingent valuation design and data treatment: If you can't shoot the messenger, change the message". Environment and Planning C. 26 (1): 34–53. Bibcode:2008EnPlC..26...34S. doi:10.1068/cav4. S2CID 55602400.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; et al. (1998), "Investigating individual motives for environmental action: Lexicographic preferences, beliefs and attitudes", in Lemons, J. (ed.), Ecological Sustainability and Integrity: Concepts and Approaches, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 46–62

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2000d). "Ecosystems, contingent valuation and ethics: The case of wetlands re-creation". Ecological Economics. 34 (2): 195–215. Bibcode:2000EcoEc..34..195S. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00158-0.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002e). "Informing and forming preferences in environmental valuation: Coral reef biodiversity". Journal of Economic Psychology. 23 (5): 665–687. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00123-X.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008b). "How much is that ecosystem in the window? The one with the bio-diverse trail". Environmental Values. 17 (2): 259–284. doi:10.3197/096327108X303882. S2CID 154274732.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Hanley, N. (1995). "Preferences, information and biodiversity preservation" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 12 (3): 191–208. Bibcode:1995EcoEc..12..191S. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(94)00056-2.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Schandl (2009), "Growth, the Environment and Keynes: Reflections on Two Heterodox Schools of Thought", Socio-Economics and Environment in Discussion (SEED) Working Papers, Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2021a). "Apologists for growth: passive revolutionaries in a passive revolution". Globalizations. 18 (7): 1123–1148. Bibcode:2021Glob...18.1123S. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.1824864. S2CID 225108741.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2021b). "'The economy' as if people mattered: Revisiting critiques of economic growth in a time of crisis". Globalizations. 18 (7): 1087–1104. Bibcode:2021Glob...18.1087S. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.1761612. S2CID 219514490.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Dobernig, K. (2017), "Theories of (Un)sustainable Consumption", in Spash, C. L. (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society, Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 203–213

- ^ Fellner, W.; Spash, C. L. (2015), "The Role of Consumer Sovereignty in Sustaining the Market Economy", in Reisch, L. A.; Thørgersen, J. (eds.), Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 394–409

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Smith, T. (2019). "Of ecosystems and economies: Re-connecting economics with reality" (PDF). Real-World Economics Review. 87 (March): 212–229.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2012b). "New foundations for ecological economics" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 77 (May): 36–47. Bibcode:2012EcoEc..77...36S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.02.004.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1997b). "Assessing the economic benefits to agriculture from air pollution control". Journal of Economic Surveys. 11 (1): 47–70. doi:10.1111/1467-6419.00023.

- ^ Hanley, N.; Spash, C. L. (1993). Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment. Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1993b). "Economics, ethics, and long-term environmental damages". Environmental Ethics. 15 (2): 117–132. doi:10.5840/enviroethics199315227.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002a). Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics. London: Routledge.

- ^ Hanley, N.; Spash, C. L. (1993). Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment. Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Biel, A. (2002). "Social psychology and economics in environmental research". Journal of Economic Psychology. 23 (5): 551–555. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00116-2.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1997a). "Ethics and environmental attitudes with implications for economic valuation". Journal of Environmental Management. 50 (4): 403–416. Bibcode:1997JEnvM..50..403S. doi:10.1006/jema.1997.0017.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2000a). "Ethical motives and charitable contributions in contingent valuation: Empirical evidence from social psychology and economics". Environmental Values. 9 (4): 453–479. doi:10.3197/096327100129342155 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Spash, C. L. (2002c), "Empirical signs of ethical concern in economic valuation of the environment", in Bromley, D. W.; Paavola, J. (eds.), Economics, Ethics, and Environmental Policy: Contested Choices, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 205–221

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2006). "Non-economic motivation for contingent values: Rights and attitudinal beliefs in the willingness to pay for environmental improvements". Land Economics. 82 (4): 602–622. doi:10.3368/le.82.4.602. S2CID 143242299.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008e), "Contingent Valuation as a Research Method: Environmental Values and Human Behaviour", in Lewis, A. (ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Psychology and Economic Behaviour, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 429–453

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2000c). "Multiple value expression in contingent valuation: Economics and ethics". Environmental Science & Technology. 34 (8): 1433–1438. doi:10.1021/es990729b.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008a). "Contingent valuation design and data treatment: If you can't shoot the messenger, change the message". Environment and Planning C. 26 (1): 34–53. Bibcode:2008EnPlC..26...34S. doi:10.1068/cav4. S2CID 55602400.

- ^ Niemeyer, S.; Spash, C. L. (2001). "Environmental valuation analysis, public deliberation and their pragmatic syntheses: A critical appraisal". Environment and Planning C. 19 (4): 567–586. Bibcode:2001EnPlC..19..567N. doi:10.1068/c9s. S2CID 59481159.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2001). "Broadening democracy in environmental policy processes". Environment and Planning C. 19 (4): 475–482. Bibcode:2001EnPlC..19..475S. doi:10.1068/c1904ed. S2CID 154405193.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2007a). "Deliberative monetary valuation (DMV): Issues in combining economic and political processes to value environmental change". Ecological Economics. 63 (4): 706–713. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.05.017.

- ^ Lo, A. Y. H.; Spash, C. L. (2013). "Deliberative monetary valuation: In search of a democratic and value plural approach to environmental policy". Journal of Economic Surveys. 27 (4): 768–789. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2011.00718.x. S2CID 62821872.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008c). "Deliberative monetary valuation and the evidence for a new value theory". Land Economics. 84 (3): 469–488. doi:10.3368/le.84.3.469. S2CID 59493446.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2007a). "Deliberative monetary valuation (DMV): Issues in combining economic and political processes to value environmental change". Ecological Economics. 63 (4): 706–713. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.05.017.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008c). "Deliberative monetary valuation and the evidence for a new value theory". Land Economics. 84 (3): 469–488. doi:10.3368/le.84.3.469. S2CID 59493446.

- ^ Lo, A. Y.; Spash, C. L. (2011). Articulation of Plural Values in Deliberative Monetary Valuation: Beyond Preference Economisation and Moralisation.

- ^ Lo, A. Y.; Spash, C. L. (2011). Articulation of Plural Values in Deliberative Monetary Valuation: Beyond Preference Economisation and Moralisation.

- ^ O'Hara, S. U. (1996). "Discursive ethics in ecosystems valuation and environmental policy". Ecological Economics. 16 (2): 95–107. Bibcode:1996EcoEc..16...95O. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(95)00085-2.

- ^ O'Hara, S. U. (2011), "The challenges of valuation: Ecological economics between matter and meaning", in Cleveland, C. J.; Stern, D. I.; R., Costanza (eds.), The Economics of Nature and the Nature of Economics, Cheltenham and Northhampton: Edward Elgar, pp. 89–110

- ^ Lo, A. Y.; Spash, C. L. (2011). Articulation of Plural Values in Deliberative Monetary Valuation: Beyond Preference Economisation and Moralisation.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002a). Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics. London: Routledge.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2008d). "The economics of avoiding action on climate change". Adbusters. 16 (1).

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2007b). "The economics of climate change impacts à la Stern: Novel and nuanced or rhetorically restricted?". Ecological Economics. 63 (4): 706–713. Bibcode:2007EcoEc..63..706S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.05.017.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2007c). "The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review". Environmental Values. 16 (4): 532–535. doi:10.3197/096327107X243277a.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2014), "Better Growth, Helping the Paris COP-out?: Fallacies and Omissions of the New Climate Economy Report", Sre-Disc, Vienna: Institute for Environment and Regional Development

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1993b). "Economics, ethics, and long-term environmental damages". Environmental Ethics. 15 (2): 117–132. doi:10.5840/enviroethics199315227.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Gattringer, C.; et al. (2017), "The Ethical Failures of Climate Economics", in Walsh, A. (ed.), The Ethical Underpinnings of Climate Economics, London: Routledge, pp. 162–182

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002a). Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics. London: Routledge.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1994b). "Trying to find the right approach to greenhouse economics: Some reflections upon the role of cost-benefit analysis". Analyse & Kritik: Zeitschrift fur Sozialwissenschafen. 16 (2): 186–199. doi:10.1515/auk-1994-0207. S2CID 156897101.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2007b). "The economics of climate change impacts à la Stern: Novel and nuanced or rhetorically restricted?". Ecological Economics. 63 (4): 706–713. Bibcode:2007EcoEc..63..706S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.05.017.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2007d). "Understanding climate change: Need for new economic thought". Economic and Political Weekly (February): 483–490.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2010). "The brave new world of carbon trading" (PDF). New Political Economy. 15 (2): 169–195. doi:10.1080/13563460903556049. S2CID 44071002.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2014b), "The Politics of Researching Carbon Trading in Australia", in Stephan, B.; Lane, R. (eds.), The Politics of Carbon Markets, London: Routledge, pp. 191–211

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Theine, H. (2018), "Voluntary Individual Carbon Trading: Friend or Foe?", in Lewis, A. (ed.), Handbook of Psychology and Economic Behaviour, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 595–624

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2011), "Carbon trading: a critique", in Dryzek, J. S. (ed.), The Oxford Handboook of Climate Change and Society, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 550–560

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2010). "The brave new world of carbon trading" (PDF). New Political Economy. 15 (2): 169–195. doi:10.1080/13563460903556049. S2CID 44071002.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2016a). "This changes nothing: The Paris Agreement to ignore reality". Globalizations. 13 (6): 928–933. Bibcode:2016Glob...13..928S. doi:10.1080/14747731.2016.1161119. S2CID 155911405.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2016b). "The political economy of the Paris Agreement on human induced climate change: A brief guide" (PDF). Real World Economics Review. 75 (June): 67–75.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2002a). Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics. London: Routledge.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2010). "The brave new world of carbon trading" (PDF). New Political Economy. 15 (2): 169–195. doi:10.1080/13563460903556049. S2CID 44071002.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Simpson, I. A. (1993). "Protecting sites of special scientific interest: intrinsic and utilitarian values". Journal of Environmental Management. 39 (3): 213–227. Bibcode:1993JEnvM..39..213S. doi:10.1006/jema.1993.1065. S2CID 153645356.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Simpson, I. A. (1994). "Spash, C. L., & Simpson, I. A. (1994). Utilitarian and Rights-based Alternatives for Protecting Sites of Special Scientific Interest". Journal of Agricultural Economics. 45 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1111/j.1477-9552.1994.tb00374.x.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Hanley, N. (1995). "Preferences, information and biodiversity preservation" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 12 (3): 191–208. Bibcode:1995EcoEc..12..191S. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(94)00056-2.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; van der Werff ten Bosch, J.; Westmacott, S.; Ruitenbeek, J.; et al. (2000), "Lexicographic preferences and the contingent valuation of coral reef biodiversity in Curaçao and Jamaica", in Gustavson, K. (ed.), Integrated Coastal Zone Management of Coral Reefs: Decision Support Modeling, Washington, D.C.: World Bank, pp. 97–118

- ^ Spash, C. L.; et al. (1998), "Investigating individual motives for environmental action: Lexicographic preferences, beliefs and attitudes", in Lemons, J. (ed.), Ecological Sustainability and Integrity: Concepts and Approaches, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 46–62

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2000d). "Ecosystems, contingent valuation and ethics: The case of wetlands re-creation". Ecological Economics. 34 (2): 195–215. Bibcode:2000EcoEc..34..195S. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00158-0.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2000b), "Assessing the benefits of improving coral reef biodiversity: The contingent valuation method", in Cesar, H. S. J. (ed.), Collected Essays on the Economics of Coral Reefs, Kalmar, Sweden, pp. 40–54

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Spash, C. L. (2008b). "How much is that ecosystem in the window? The one with the bio-diverse trail". Environmental Values. 17 (2): 259–284. doi:10.3197/096327108X303882. S2CID 154274732.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Aslaksen, I. (2015). "Re-establishing an ecological discourse in the policy debate over how to value ecosystems and biodiversity" (PDF). Journal of Environmental Management. 159 (August): 245–253. Bibcode:2015JEnvM.159..245S. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.04.049. PMID 26027754. S2CID 3584039.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Hache, F. (2021). "The Dasgupta Review deconstructed: An exposé of biodiversity economics". Globalizations. May (5): 653–676. doi:10.1080/14747731.2021.1929007. S2CID 236360919.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Hanley, N. (1995). "Preferences, information and biodiversity preservation" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 12 (3): 191–208. Bibcode:1995EcoEc..12..191S. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(94)00056-2.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2000d). "Ecosystems, contingent valuation and ethics: The case of wetlands re-creation". Ecological Economics. 34 (2): 195–215. Bibcode:2000EcoEc..34..195S. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00158-0.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; van der Werff ten Bosch, J.; Westmacott, S.; Ruitenbeek, J.; et al. (2000), "Lexicographic preferences and the contingent valuation of coral reef biodiversity in Curaçao and Jamaica", in Gustavson, K. (ed.), Integrated Coastal Zone Management of Coral Reefs: Decision Support Modeling, Washington, D.C.: World Bank, pp. 97–118

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2000a). "Ethical motives and charitable contributions in contingent valuation: Empirical evidence from social psychology and economics". Environmental Values. 9 (4): 453–479. doi:10.3197/096327100129342155 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Spash, C. L.; Urama, K. C.; Burton, R.; Kenyon, W.; Shannon, P.; Hill, G. (2004), Understanding the Value of Biodiversity in Water Ecosystems: Economics, Ethics and Social Psychology, Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Ryan, A. M. (2012). "Economic schools of thought on the environment: Investigating unity and division". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 36 (5): 1091–1121. doi:10.1093/cje/bes023. hdl:10.1093/cje/bes023.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Ryan, A. M. (2011). "Is WTP an attitudinal measure?: Empirical analysis of the psychological explanation for contingent values" (PDF). Journal of Economic Psychology. 32 (5): 674–687. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.07.004.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Hache, F. (2021). "The Dasgupta Review deconstructed: An exposé of biodiversity economics". Globalizations. May (5): 653–676. doi:10.1080/14747731.2021.1929007. S2CID 236360919.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2021c). "The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, Partha Dasgupta, HM Treasury, London (2021), ISBN: 978-1-911680-29-1". Biological Conservation. 264 (December): 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109395. S2CID 244279314.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2020). "A tale of three paradigms: Realising the revolutionary potential of ecological economics". Ecological Economics. 169 (March): 106518. Bibcode:2020EcoEc.16906518S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106518. S2CID 213977638.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1999). "The development of environmental thinking in economics". Environmental Values. 8 (4): 413–435. doi:10.3197/096327199129341897.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2011a). "Social ecological economics: Understanding the past to see the future" (PDF). Journal of Economics and Sociology. 70 (2): 340–375. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2011.00777.x.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2012b). "New foundations for ecological economics" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 77 (May): 36–47. Bibcode:2012EcoEc..77...36S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.02.004.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2012a), "Towards the Integration of Social, Economic and Ecological Knowledge", in Gerber, J.-F.; Steppacher, R. (eds.), Towards an Integrated Paradigm in Heterodox Economics, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 26–46

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2011b), "Social Ecological Economics: Understanding the Past to See the Future", in Lee, F. S. (ed.), Social, Methods, and Microeconomics: Contributions to Doing Economics Better, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 39–74

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2012b). "New foundations for ecological economics" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 77 (May): 36–47. Bibcode:2012EcoEc..77...36S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.02.004.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Smith, T. (2019). "Of ecosystems and economies: Re-connecting economics with reality" (PDF). Real-World Economics Review. 87 (March): 212–229.

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Smith, T. (2019). "Of ecosystems and economies: Re-connecting economics with reality" (PDF). Real-World Economics Review. 87 (March): 212–229.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2017a), "Soziales, ökologisches und ökonomisches Wissen: Zum Synthetisierungspotenzial des Critical Realism", in Lindner, U.; Mader, D. (eds.), Critical Realism meets kritische Sozialtheorie: Ontologie, Erklärung und Kritik in den Sozialwissenschaften (in German), Bielefeld: Transkript Verlag, pp. 217–242

- ^ Spash, C. L. (1999). "The development of environmental thinking in economics". Environmental Values. 8 (4): 413–435. doi:10.3197/096327199129341897.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2009). "The new environmental pragmatists, pluralism and sustainability". Environmental Values. 18 (3): 253–256. doi:10.3197/096327109x12474739376370. S2CID 153618844.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2011a). "Social ecological economics: Understanding the past to see the future" (PDF). Journal of Economics and Sociology. 70 (2): 340–375. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2011.00777.x.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2013). "The shallow or the deep ecological economics movement?" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 93 (September): 351–362. Bibcode:2013EcoEc..93..351S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.05.016. S2CID 11640828.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2017b), "Social Ecological Economics", in Spash, C. L. (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society, Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 3–16

- ^ Spash, C. L.; Ryan, A. M. (2012). "Economic schools of thought on the environment: Investigating unity and division". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 36 (5): 1091–1121. doi:10.1093/cje/bes023. hdl:10.1093/cje/bes023.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2020). "A tale of three paradigms: Realising the revolutionary potential of ecological economics". Ecological Economics. 169 (March): 106518. Bibcode:2020EcoEc.16906518S. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106518. S2CID 213977638.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2021a). "Apologists for growth: passive revolutionaries in a passive revolution". Globalizations. 18 (7): 1123–1148. Bibcode:2021Glob...18.1123S. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.1824864. S2CID 225108741.

- ^ Spash, C. L. (2017b), "Social Ecological Economics", in Spash, C. L. (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society, Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 3–16