Climate change in France

In France, climate change has caused some the greatest annual temperature increases registered in any country in Europe.[1] The 2019 heat wave saw record temperatures of 46.0 °C.[2] Heat waves and other extreme weather events are expected to increase with continued climate change. Other expected environmental impacts include increased floods due to both sea level rise and increased glacier melt.[3][4] These environmental changes will lead to shifts in ecosystems and affect local organisms.[5] Climate change will also cause economic losses in France, particularly in the agriculture and fisheries sectors.[6][7]

The Paris Agreement on climate change, under France's presidency, was negotiated and agreed in 2015 at COP21. France subsequently set a law to have a net zero atmospheric greenhouse gas emission (carbon neutrality) by 2050.[8] Recently, the French government has received criticism for not doing enough to combat climate change, and in 2021 was found guilty in court for its insufficient efforts.[9]

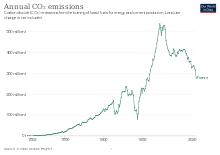

Greenhouse gas emissions

France strives to have reduced its greenhouse gas emissions to 40% below what it was in 1990 by 2030.[10] The French government hopes to reach a net emission of zero by 2040.[11]

The table below shows the annual total emission of greenhouse gas in France in Megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2). Values for EU27 with the United Kingdom (previously EU28) as well as the values for the world are included to compare trends in emission.[12]

| Year | France (Mt CO2) | EU27 + UK (Mt CO2) | World (Mt CO2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 386 | 4,408 | 22,683 |

| 2005 | 408 | 4,249 | 30,051 |

| 2019 | 314 | 3,303 | 38,016 |

The four main emitting sectors in France are transport, agriculture, buildings and industry.[13][14] In 2017, the French industry (including energy supply and other manufacturing) was responsible for 46% of the total CO2 emission, a number that has been fairly steady since around 2014.[15] The industries and agriculture are responsible for just 20% each of France's CO2 emissions.[13]

For the total CO2 emission in 2018, France ranked number 19 in the world with a total of 330Mt CO2 emitted, just below Poland with 340Mt CO2 emitted and the United Kingdom with 370Mt CO2 emitted.[16]

The table below shows the annual emission of greenhouse gas in France in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per capita (tCO2/capita).[17]

| Year | France(t CO2/capita) | EU27 + UK (t CO2/capita) | World (t CO2/capita) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 9.18 | 9.52 | 4.26 |

| 1980 | 9.38 | 10.27 | 4.46 |

| 1990 | 6.78 | 9.24 | 4.26 |

| 2000 | 6.75 | 8.46 | 4.18 |

| 2010 | 6.02 | 7.78 | 4.88 |

| 2019 | 4.81 | 6.47 | 4.93 |

The per capita emission of France in 2019 was just below the average for the world. In 2018, France ranked number 17 in the world with 5.19 tonnes CO2 emitted per capita. Its neighbouring countries the United Kingdom (5.62T CO2/capita) and Germany (9.12T CO2/capita) ranked 14 and 9, respectively.[16]

Impacts on the natural environment

The current rise in temperature is changing the natural environment in France, from more precipitation during spring and winter to heat waves and fast melting glaciers. All these impacts are only expected to get worse with the increasing temperature.

Temperature and weather changes

During the 20th century, the average annual temperature in mainland France rose by 0.95 °C. Meanwhile, the average annual global temperature rose by 0.74 °C during that same time period. Meaning that France saw an average temperature increase that was around 30% higher compared to the average global temperature rise. If this trend continues by the time the average global temperature has reached 2 °C it would mean that the average temperature in France has increased with almost 3 °C. In present day, warmer summers and cooler winters are already getting more pronounced leading to an increase of 5–35% in autumn and winter rainfall as well as a decrease in summer rainfall,[1] the latter combined with an increase in temperature, could increase the risk for more severe drought events. The Mediterranean part of the country saw an increase of around 0.5 °C per decade in the period of 1979–2005,[21] making it the part of the country that is experiencing the highest increase in temperature and highest decrease in annual precipitation.[5]

Temperature rise in the French Alps is even more extensive than in the rest of the country, and by 2018 approached a 2 °C average increase compared to the industrial revolution with an accelerating increase in the past few decades.[5][22]

Temperature records

The hottest year in France on record was in 2020 with an average temperature of 14.0 °C which beat the last record of 13.9 °C in 2018.[23] The all-time hottest day was recorded on the 28th of June 2019, a day that saw a lot of new records during the 2019 European heat wave. With the hottest place being in Gallargues-le-Monteux in Southern France with a staggering 45.9 °C.[2] Due to an increase in global average temperature France has been hit by several extreme heat waves over the past few years, this is because of hot air passing over Europe from North Africa.[24]

Heat waves

With a decrease in summer precipitation and a global increase of average temperature, heat wave events like the 2018 European heat wave and the 2019 European heat wave set new summer temperature records and are only expected to get more intense and common due to climate change.[25]

Sea-level rise

With an increase in glacier and polar ice cap melting, sea level rise is expected to increase, affecting both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean coasts. Future climate projections predict that sea levels around France will increase by at least 1 meter by the year 2100.[3] Low coasts will be in danger of erosion and being permanently submerged, heavily threatening coastal infrastructure, new coasts will be under threat from temporal flooding, an estimated 140,000 homes and 80,000 people are located in the zone that is at risk for permanent submersion by 2100.[1]

Glaciers

An increase in mean annual temperature causes glacial retreat. In the European Alps it is estimated that around half of glacial ice had disappeared between 1850 and 1975. Another 30–40% from what remained was estimated to have disappeared between the time period 1980–2005.[26] According to future climate models, what remains of the glaciers in the Alps as of the year 2100 compared to 2017, could be nothing more than one-third in a best case scenario regardless if the global carbon emission hits zero. If these emissions continue to rise those glaciers will be gone by 2100.[27][28] At the Mont Blanc altitudes between 1500 and 2500 meters saw a total of 25 more snow-free days when comparing the years 1964–75 and 2005–2015.[5] An increasing temperature is the primary cause of this rapid snow melting from glaciers, making more ground become exposed to sunlight which changes the albedo of the surrounding area. This secondary cause creates in its turn a positive feedback effect of more extensive heat and therefore promoting even more glacial and snow melt.

A rapid rise in melting glaciers increases the risk of avalanches, floods, mudslides and landslides. A reduction in melting glacial water causes problems for local water reservoirs used for energy, agriculture and daily use of water. This causes high risk as parts of the Alps are densely populated.[4]

Flooding

France is in present-day not under serious threat of flooding because of climate change. However, with an expected sea-level rise, coastal regions are likely to get effected by coastal flooding. Other than that future climate projections have difficulties estimating where and when an increase in flooding events might occur due to high uncertainties in weather patterns. High altitude areas, like the French Alps, are most likely to see more flooding events due to melting glaciers and because of mountains being good at capturing rain from the air.[29]

Ecosystems

More than half of all land in France belongs to agriculture or urban areas, both of which are generally biodiverse poor ecosystems. The most numerous naturally occurring ecosystem is forests. In France around 27% of land and 36% of marine environments fall under some form of protection, like Natura 2000 or the Habitats directive.[30] Current conservation plans to help existing organisms and ecosystems cope with a changing climate is to reduce any other forms of pressure like human interference in order to promote the resilience in those ecosystems as well as more protected areas and stricter rules, legislation and management.[31]

Biodiversity

Plant communities affect the biophysical properties of their surrounding soil through interactions with both microbial communities and animals as well as through adding soil from decaying plant matter and root growth which holds both water and soil in place.[32] With a shift in climate these communities will have to move as well. For plant communities living in the Alps, this is more problematic as according to one source a roughly 100 meter change in altitude corresponds to a difference of 0.5 °C.[5]

A higher winter temperature could also be devastating for many forms of hibernating wildlife, as an early spike in temperature would promote hibernating organisms like cold-blooded reptiles and amphibians to wake up, as well as cause plants to flower early. Most of these organisms would not survive if a late winter cold snap were to hit the area. An example is the blueberry, which is sensitive to frost and can therefore become severely damaged if its productivity starts to early.[5]

Impacts on people

Economic impacts

Agriculture

Climate change is expected to bring longer, warmer summers and less precipitation to France, which will severely affect many of the crops used in agriculture. Due to the warmer weather, the evaporation will be higher and less rain is expected. As most crops currently grown in France are to some extent sensitive to drought, there will likely be a higher need for irrigation, leading to a higher cost of crop production.[6] Extreme weather events and droughts can also eliminate crop yields for some years.[33] The warm weather, although it will prolong the growing season, will also shorten the crop growth phases and crops such as oilseed and cereal will hence experience a shorter grain filling phase, resulting in smaller size.[6] The smaller size also means a smaller yield volume, resulting in the need to expand current agriculture or import additional crop.

Livestock will also be affected by the warmer climate. Animals kept indoors will have a higher need for ventilation and cooling systems, and animals let outdoors will need shelter to protect from the sun during grazing, and likely need a higher water supply available,[6] increasing the cost of production. The biggest impact on livestock production will possibly be through fodder yield reduction. The warmer weather will alter the seasonal growth, decreasing the summer yields, while likely giving an increase in spring and autumn yields, resulting in a skewed and variable fodder availability.[6] Due to the effects of climate change on livestock, and the effect of livestock on climate change, it is likely necessary to rethink the livestock system.

Vineyards

Along with Italy and Spain, France is one of the largest wine producers in the world, with vineyards found in all regions of France.[34] Wine production is the second largest trade in France, after aeronautics. In 2017, French wine production had a profit of 8.24 billion Euros (9.97bn USD).[35]

High temperatures during the grape maturation period can lead to a reduced quality of the grapes. Drier weather also causes a decreased annual yield, unless more efficient irrigation systems are implemented on vineyards, with the effect of increasing the production costs.[6] The quality of the wine may also decrease, as the warmer temperature-effects on the grapes gives it a higher sugar content, and hence higher alcohol degree, but also a lower acid content.[6]

But the warmer climate also allows for new opportunities, for example moving wine production further north. Existing vineyards located in the north of France, such as those in Champagne, are expected to experience optimal conditions for wine production.[6]

Fisheries

There are a lot of uncertainties about how the future fish stocks along the French coasts will behave. Changes in migratory patterns, trophic interactions, vulnerability to fishing pressure and general fish stock production are difficult to predict as they depend on more factors than just the changing climate.[7] More recent observations report variable effects on different species. In the Bay of Biscay, for example, the anchovy catches are increasing due to a warmer climate, whereas catches of pollack and monkfish are declining.[7] Conversely, France has a fish consumption that exceeds their catch volumes, and already import fish to sustain their demand.[36] With altered future catches, the need for imported fish may increase, imposing a bigger expense than currently.

France is one of the biggest producers of marine molluscs in Europe,[36] farming both oysters and mussels.[37] With climate change, the ocean will take up increased quantities of CO2, resulting in ocean acidification. Calcifying organisms, such as shellfish, will have a harder time producing their skeletal structures, hence decreasing growth rates and potentially increasing mortality.[38] This could lead to significant economic loss for France. For all of Europe, the predicted economic losses due to mollusc production damage is calculated to annually be almost 0.9 billion Euro (1bn USD) by 2100.[38]

Infrastructure

Climate change, bringing increased temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events, will highly impact the French infrastructure. Temperature increases the degradation of asphalt, and flooding and big rain events cause the risk of dislodging parts of the road.[39] Railways may also be dislodged, and high temperatures may further make the tracks expand and buckle, causing the need for reparation. Tunnels and other low infrastructures will also be severely affected by extreme rain events and flooding.[39] All together, this will slow down transports while increasing operating maintenance and costs.

Flooding due to sea-level rise will further affect infrastructure in coastal areas. The water rise will cause loss of roads and buildings, and further cause people to lose their houses and jobs.[40] Increased expenses will come either from building structures to increase flood protection, or from redeveloping and rebuilding transport infrastructures and relocating people in the affected areas.[40]

Health impacts

France is one of the countries worst affected by European heat waves. During the heat wave of 2003, where big parts of France measured over 40 °C (104 °F), closer to 15,000 people died due to the elevated temperatures. Up until that year, heat wave events had been underestimated as a threat to the French public health.[41] Since then, local authorities have undertaken measures to be more prepared. During the heat waves of 2018 and 2019, despite the latter reaching record high temperatures of 45.9 °C (114.6 °F),[2] fatalities reached approximately 1,500 people each year.[42] With climate change, heat waves are expected to get more intense and frequent in France,[25] and the number of fatalities with it.

Deaths due to air pollution has likely been undervalued in France.[43] Premature deaths due to pulmonary diseases and stroke were previously estimated to 16,000 fatalities annually.[13][44] More recently, the premature deaths due to the levels of particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrous oxide (NO2) and ozone (O3) were calculated to be over 40,000 people annually.[45] Climate change affects the flow and development of air pollutants and is likely to decrease the over-all health of the population, though it is very difficult to predict what the exact effects will be.[46]

With a warmer climate, like that brought about by climate change, there is a risk of an increase in vector- borne diseases such as yellow fever, dengue fever[47] and malaria.[48] Leishmaniasis, a disease transmitted by sandflies, is currently found only in the Mediterranean area, but could spread northwards with a warmer climate.[47] While a warmer climate will likely bring more favourable conditions for the vectors, the exact effects or the extent of the spread also depend on factors such as socioeconomic status and land-use as well as available treatments.[48]

Mitigation

Energy transition

In 2017, the industrial sectors were responsible for 17.6% of the French total energy consumption, with the non industrial sectors standing for the remaining 82.4% of the total energy consumption.[15]

The total energy supply of France in 2019 relied mainly on nuclear power (just over 40%) and oil (30%). The use of coal accounted for only 5% of the total energy supply and natural gas for just over 15%. The rest came from renewable sources, such as biofuel and hydropower.[11]

The Energy Transition Ministry is increasing wind power.[49] Solar power is also being increased so the country will depend on both nuclear and renewables.[50]

France has set a goal to get 32% of its total consumed energy from renewable sources by 2030. They also hope to reduce the share of nuclear power for generating electricity from 70% to 50% until 2030 (in 2020, it is still approximately 70%[11]). France further intends to close its last coal plant by 2022,[11] which would make them the fourth coal-free state in Europe, following after Belgium, Austria and Sweden.[51] All efforts are in line with a target of carbon neutrality law, which France hopes to reach by 2050.[8]

France has made an effort to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions in the power and transport sector, where they have almost phased out their coal usage and reduced the number of gas cars.[13] Unfortunately, about 90% of all road traffic still runs on oil products,[13] and they have not managed to reduce the number of vehicles in favour of public transportation, or biking.[13][52] Within the building sector, new houses are built to be low-consuming of energy, and France hopes that the construction of energy-plus houses will be standard after 2021.[13] The industry sector is doing a good job in reducing its carbon emissions, but are still not able to keep their limit when it comes to for example energy usage in installations for metals, minerals and the waste management industry.[13][52]

Policies and legislation

The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) are set by the European Union, as an implementation of the Paris Agreement. The overall goal is to reach a 43% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 compared to 2005. According to this, France should carry out adaptive measures to reduce its emissions by 37% until 2030, compared to 2005.[53] Further, France has set a law to achieve climate neutrality in 2050.[8]

France is currently insufficient in its efforts to reach the goal, which led to a government lawsuit in 2021.[54]

In December 2022 the European Commission approved a law forbidding short-haul flights in France, if people can pass the distance on a train in 2.5 hours. Greenpeace demanded to extend the law, by following the advice of the European Commission to include connecting flights. Greenpeace cited a report according to which, if it will be 6 hours instead of 2.5, it will cut global greenhouse gas emissions by an amount equivalent to 3.5 million tonnes CO2 annually.[55]

According to the French president Emmanuel Macron France will end sales of petrol and diesel vehicles by 2040 to meet its targets under the Paris climate accord. The Netherlands is expected to have the same ban by 2025 and some parts of Germany will have a phase-out by 2030.[56] In 2021, French lawmakers also set out to ban domestic flights where train rides taking under two and a half hours are available, in an effort to reduce CO2 emissions.[57]

International cooperation

France hosted the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, where the landmark Paris Agreement was negotiated and agreed. The agreement forms a key international framework for climate change mitigation and adaptation.[58]

Adaptation

To adapt to climate change, France has made a National Adaptation Plan. They are currently on the second one, called The Second National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change (NAP-2 or PNACC-2), which is in place from 2018 until 2022.[59] The plan is based on the first plan that was in place from 2011 to 2015, and was revised with a national consultation involving 300 representatives and experts.[59] The plan includes adaption strategies for the main economic and social sectors in the country as well as for the different territories in France.[13][59]

Society and culture

Lawsuits

In 2021 the French government was found guilty of not keeping its pledges to reduce greenhouse gases. A court in France convicted the government after four non-governmental organizations (NGO's) had collected 2.3 million signatures from the French people for their petition, which is the largest amount of collected signatures in history.[9][54] NGO's include Greenpeace France and Oxfam France. The petition was created to counteract the current lack of action the French government was doing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions despite having promised to reduce its GHG emission with 40% by the year 2030 and going carbon neutral by 2050. The NGO's accused the government of currently dealing with the climate problem in a pace that is going twice as slow.[54] Between the years 2018-19 the GHG emission in France dropped by 0.9% instead of the annual target of 1.5% until the year 2025.[9] Each organisation was awarded a symbolic €1 by the French government.[9][54]

Activism

In August 2019 a summit of the G7 members convened in Biarritz, France. In protest of the country doing too little to stop their carbon emissions, protesters marched in the nearby city of Bayonne, as Biarritz had been under lockdown due to the summit. The protesters held portraits of Emmanuel Macron upside down to highlight the gap between the president's climate goals and the lack of action thereof.[60] The more than 100 portraits of the president had been stolen from French town halls all over the country, many activists were held responsible for "group theft by deceit".[61] Despite the trials, more than 9,000 protesters showed up and marched with the inverted portraits. The protests were eventually broken up with tear gas and water cannons and around 70 people were arrested.[60]

The Yellow vest movement was initially started in France due to a public wide outrage over the increase in fuel prices. In 2018 the price of diesel saw an increase by 20%, the added on carbon tax and the overall increase of the price of fuel was done by the government to take climate action and reduce the number of times people would use cars or other forms of personal transportation. The only problem was that the people who got affected the most by this were also the once that could not afford it and only had their cars as means of transportation. The increased price was done in favour of people living in the city where public transportation is plentiful, but this is not the case in rural regions and on the countryside, thus starting the movement.[62]

Public perception of climate change

A nationwide survey in 2017 containing answers from 3,480 French citizens looked at how the general public perceived climate change. According to the study 85% of people believe climate change is happening with only 1.9% being absolutely not sure. A total of 90% of participants believed that human activity is completely or partly responsible for climate change and only 2.5% were found to be climate change deniers. Around 85% showed concern about the effects of climate change. Most concerned were younger people, students and those who are full-time employed. On the other hand, the number of people that believed that their actions could mitigate climate change was found to only be moderate. With many people not knowing what actions to take or believing that their actions would not make any difference. The survey also found that the public's knowledge about climate change was low to moderate, while being high in mid-range educational qualifications, students, the full-time employed and those that had experienced the direct effects of climate change through droughts, floods or extreme storms.[63]

Information about climate change in weather forecasts

In February 2023, 2 state TV channels, France 2 and France 3 have begun to enter information regarding climate change in their weather forecasts. This will make the forecasts 1.5–2 minutes longer. The climate related information will rely on experts. The channels will also provide information about climate change and the ways stopping it to their workers. In France, except in case of breaking news they will ask reporters to take the train instead of a plane.[64]

See also

References

- ^ a b c National Observatory for the Impacts of Global Warming. Climate change: costs of impacts and lines of adaptation. Report to the Prime Minister and Parliament, 2009. Accessed 2021-08-21

- ^ a b c "France records all-time highest temperature of 45.9C". The Guardian. 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- ^ a b "Coastal floods in France". Climatechangepost.com. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ a b "Glacial Retreat in the Alps". Archived from the original on 2016-11-12.

- ^ a b c d e f "Climate change and its impacts in the Alps". Crea Mont Blanc. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h AgriAdapt. SUSTAINABLE ADAPTATION OF TYPICAL EU FARMING SYSTEMS TO CLIMATE CHANGE. Retrieved 2021-04-26

- ^ a b c Mcilgorm, A.; Hanna, S.; Knapp, G.; Le floc'h, P.; Millerd, F.; Pan, M. (2010). "How will climate change alter fishery governance? Insights from seven international case studies". Marine Policy. 3 (1): 170–177. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2009.06.004 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b c "What is carbon neutrality and how can it be achieved by 2050? | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 2019-03-10. Archived from the original on 2019-10-04. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ a b c d "Court convicts French state for failure to address climate crisis". The Guardian. 2021-02-03. Archived from the original on 2021-02-03. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ "Report on the Implementation by France of the Sustainable Development Goals" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-19. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ a b c d "France - Countries & Regions". IEA. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Crippa, M., Guizzardi, D.,Muntean, M., Schaaf, E., Solazzo, E.,Monforti-Ferrario, F., Olivier, J.G.J., Vignati, E. Fossil CO2 emissions of all world countries. Retrieved 2021-04-21

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "France: CLIMATE TRANSPARENCY REPORT" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-11-18.

- ^ European Union. 2009 French climate plan. Retrieved 2021-04-24

- ^ a b European Environmental Agency. France - industrial pollution profile 2020. Retrieved 2021-04-22

- ^ a b "Each Country's Share of CO2 Emissions | Union of Concerned Scientists". www.ucsusa.org. Archived from the original on 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ "EDGAR - The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research". edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2009-06-28. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Hausfather, Zeke; Peters, Glen (29 January 2020). "Emissions – the 'business as usual' story is misleading". Nature. 577 (7792): 618–20. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..618H. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00177-3. PMID 31996825.

- ^ Schuur, Edward A.G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847.

Medium-range estimates of Arctic carbon emissions could result from moderate climate emission mitigation policies that keep global warming below 3°C (e.g., RCP4.5). This global warming level most closely matches country emissions reduction pledges made for the Paris Climate Agreement...

- ^ Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

"The IPCC doesn't make projections about which of these scenarios is more likely, but other researchers and modellers can. The Australian Academy of Science, for instance, released a report last year stating that our current emissions trajectory had us headed for a 3°C warmer world, roughly in line with the middle scenario. Climate Action Tracker predicts 2.5 to 2.9°C of warming based on current policies and action, with pledges and government agreements taking this to 2.1°C.

- ^ "Droughts France". Archived from the original on 2016-07-21.

- ^ "Climate change: why the Alps are particularly affected". Archived from the original on 2016-04-18.

- ^ "2020 was France's hottest year". The News. 2020-12-30. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- ^ "What is causing the European heatwave?". The Guardian. 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- ^ a b "France's record-breaking heatwave made 'at least five times' more likely by climate change". Carbon Brief. 2019-07-02.

- ^ Haeberli (2007). "Integrated monitoring of mountain glaciers as key indicators of global climate change: the European Alps". Annals of Glaciology. 46 (1): 150–160. Bibcode:2007AnGla..46..150H. doi:10.3189/172756407782871512. S2CID 16420268.

- ^ Zekollari (2019). "Modelling the future evolution of glaciers in the European Alps under the EURO-CORDEX RCM ensemble". The Cryosphere. 13 (4): 1125–1146. Bibcode:2019TCry...13.1125Z. doi:10.5194/tc-13-1125-2019. hdl:20.500.11850/338400. S2CID 134009284.

- ^ "Two-thirds of glacier ice in the Alps 'will melt by 2100'". The Guardian.

- ^ "River floods France". Climatechangepost.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-06.

- ^ "France". Biodiversity Information System of Europe. Archived from the original on 2014-04-22. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ^ "Biodiversity France". Climate Change Post. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ^ Stokes (2021). "Shifts in soil and plant functional diversity along an altitudinal gradient in the French Alps". BMC Research Notes. 14 (1): 54. doi:10.1186/s13104-021-05468-0. PMC 7871617. PMID 33557933.

- ^ "EEA Signals 2015 - Living in a changing climate — European Environment Agency". www.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ "World wine production reaches record level in 2018, consumption is stable | BKWine Magazine |". BKWine Magazine. 2019-04-14. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ Ugaglia, AA; Cardebat, J; Jiao, L. "The French Wine Industry". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ a b FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Impacts of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture. Retrieved 2021-04-26

- ^ Philippe G, Maurice H. 1997. Marine Molluscan Production Trends in France: From Fisheries to Aquaculture

- ^ a b European commission. Europe could suffer major shellfish production losses due to ocean acidification. Retrieved 2021-04-26

- ^ a b Caisse des Dépôts. CLIMATE CHANGE VULNERABILITIES AND ADAPTATION POSSIBILITIES FOR TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURES IN FRANCE. Retrieved 2021-04-26

- ^ a b UNECE. Infrastructure and transport systemsAdapting to climate changeMeasurements of French NAPCC Retrieved 2021-04-26

- ^ Poumadère, Marc; Mays, Claire; Mer, Sophie Le; Blong, Russell (2005). "The 2003 Heat Wave in France: Dangerous Climate Change Here and Now". Risk Analysis. 25 (6): 1483–1494. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00694.x. ISSN 1539-6924. PMID 16506977. S2CID 25784074.

- ^ "20,000 deaths since 1999: New report reveals deadly impact of extreme weather in France". www.thelocal.fr. Archived from the original on 2019-12-05. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ "Air pollution deaths are double earlier estimates: study". France 24. 2019-03-12. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ "Ambient air pollution". www.who.int. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ "France - Air pollution country fact sheet — European Environment Agency". www.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ European Union. Air Pollution and Climate Change. Retrieved 2021-04-24

- ^ a b WHO, World Health Organization. CLIMATE AND HEALTH COUNTRY PROFILE – 2015 FRANCE. Retrieved 2021-04-24

- ^ a b Semenza, Jan C.; Menne, Bettina (2009-06-01). "Climate change and infectious diseases in Europe". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 9 (6): 365–375. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70104-5. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 19467476.

- ^ Messad, Paul (2023-03-28). "EDF selected to build France's largest offshore wind farm". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ Todorović, Igor (2022-09-23). "Macron: France can't rely either on renewables or on nuclear power alone". Balkan Green Energy News. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ Simon, Frédéric (2020-04-21). "Sweden adds name to growing list of coal-free states in Europe". www.euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 2020-04-22. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ a b "Plan de relance". www.economie.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ European Union. Update of the NDC of the European Union and its Member States. Retrieved 2021-04-27

- ^ a b c d "France not doing enough to tackle climate change, court rules". CNN. 2021-04-21.

- ^ Massy-Beresford, Helen. "European Commission Approves French Domestic Short-Flight Ban". Routes. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ France to ban sales of petrol and diesel cars by 2040 Guardian 6 July 2017

- ^ "France moves to ban short-haul domestic flights". BBC News. 2021-04-12. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ "Paris climate change agreement: the world's greatest diplomatic success". the Guardian. 2015-12-14. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ a b c "French National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change for the period 2018-2022 launched — Climate-ADAPT". climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ a b "French climate activists protest as Macron attends G7 summit". The Guardian. 2019-07-25. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ "Taking Macron down: climate protesters strip French town halls of portraits". The Guardian. 2019-07-02. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ Jetten (2020). "How Economic Inequality Fuels the Rise and Persistence of the Yellow Vest Movement". International Review of Social Psychology. 33. doi:10.5334/irsp.356.

- ^ Babutsidze (2018). "Public Perceptions and Responses to Climate Change in France". Université Côte d'Azur: Nice.

- ^ Hird, Alison (14 March 2023). "French TV transforms weather forecasts to include climate change context". RFI. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

External links

Media related to Climate change in France at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Climate change in France at Wikimedia Commons