Citipati

| Citipati Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nesting Citipati specimen nicknamed "Big Mama", at the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Oviraptoridae |

| Subfamily: | †Oviraptorinae |

| Genus: | †Citipati Clark et al., 2001 |

| Type species | |

| †Citipati osmolskae Clark et al., 2001 | |

Citipati ([ˈtʃiːt̪ɪpət̪i]; meaning "funeral pyre lord") is a genus of oviraptorid dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. It is mainly known from the Ukhaa Tolgod locality at the Djadochta Formation, where the first remains were collected during the 1990s. The genus and type species Citipati osmolskae were named and described in 2001. A second species from the adjacent Zamyn Khondt locality may also exist. Citipati is one of the best-known oviraptorids thanks to a number of well-preserved specimens, including individuals found in brooding positions atop nests of eggs, though most of them were initially referred to the related Oviraptor. These nesting specimens have helped to solidify the link between non-avian dinosaurs and birds.

Citipati was among the largest oviraptorids; it is estimated to have been around 2.5–2.9 m (8.2–9.5 ft) in length and to have weighed 75–110 kg (165–243 lb). Its skull was highly pneumatized, short, and had a characteristic crest formed by the premaxilla and nasal bones. Both upper and lower jaws were toothless and developed a horny beak. The tail ended in a pygostyle (the fusion of the last caudal vertebrae), which is known to support large rectrices.

The taxon is classified as an oviraptorid, a group of very bird-like feathered dinosaurs that had robust, parrot-like jaws. It is among the oviraptorid species that preserve nesting specimens. Citipati laid elongatoolithid eggs in a circular mound-shaped nest, where the parents brooded the eggs by sitting on the nest with their arms covering the nest perimeter. Both arms and tail were covered in long feathers, which likely protected both juveniles and eggs from weather. Citipati may have been an omnivorous oviraptorid, given that the remains of two young individuals of the contemporaneous troodontid Byronosaurus were found in a nest, likely preyed and brought by an adult Citipati to feed its hatchlings. It is also possible that these small Byronosaurus were hatched by the Citipati as a product of nest parasitism.

History of discovery

In 1993, a small fossilized oviraptorid embryo, labelled as specimen IGM 100/971, was discovered in a nest at the Ukhaa Tolgod locality of the highly fossiliferous Djadokhta Formation, Gobi Desert, during the Mongolian Academy of Sciences-American Museum of Natural History paleontological project. The expedition also discovered numerous mammal, lizard, theropod, ceratopsian and ankylosaurid fossils remains at this locality, with the addition of at least five types of fossil eggs in nests. The oviraptorid embryo is composed of a nearly complete skeleton and was found in a badly weathered semi-circular nest, which also included two perinate (hatchlings or embryos close to hatching) skulls less than 5 cm (50 mm) of an unknown dromaeosaurid taxon. One of these skulls was reported to preserve portions of an eggshell. Both embryonic oviraptorid and dromaeosaurid skulls were briefly described by the paleontologist Mark A. Norell and colleagues in 1993, who considered this oviraptorid embryo to be closely related to the early named Oviraptor, and also as an evidence supporting that oviraptorids were brooding animals.[1] The two perinates would be later identified as individuals belonging to the troodontid Byronosaurus.[2]

During the same year 1993, expeditions of the paleontological project of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences-American Museum of Natural History discovered a large adult oviraptorid specimen also from the Ukhaa Tolgod locality of the Djadokhta Formation, in a sublocality known as Ankylosaur Flats. This new specimen was labelled under the specimen number IGM 100/979 and includes a partial skeleton comprising some ribs and partial limbs but lacking the skull, neck and tail. It was found in a nesting pose, sitting atop a nest of elongatoolithid eggs with folded forelimbs and crouched hindlimbs. Similar to the embryonic specimen, IGM 100/979 was considered to be an indeterminate oviraptorid closely related to Oviraptor.[3] The specimen shortly became famous and was nicknamed as "Big Mama" by The New York Times press.[4] A larger and more complete specimen, catalogued as IGM 100/978, was found in 1994 also from the Ankylosaur Flats sublocality by the American Museum–Mongolian Academy of Sciences field expeditions. The specimen was unearthed as a single individual not associated with eggs, and it is represented by a nearly complete skeleton including the skull and much of the postcranial elements. However, it was initially identified as a specimen of Oviraptor.[5]

In 1995, the Mongolian Academy of Sciences-American Museum of Natural History expedition discovered a second nesting oviraptorid specimen from the Ukhaa Tolgod locality, in a region called Camel's Humps, at the Death Row sublocality. This new specimen was labelled as IGM 100/1004 and nicknamed "Big Auntie".[6][5] The excavation lasted several days of work and a filming crew registered some of the excavation progress through video-documentary and photography. The professional team had to remove some of the sediments surrounding the specimen as the terrain was irregular and it was too heavy to be safely transported to the escarpment. As most fossils of the Ukhaa Tolgod locality have a relatively good preservation and exposure, the lack of associated nests argues against the possibility for this sublocality to be an oviraptorid nesting site. IGM 100/1004 is slightly more complete than 100/979; it preserves the entire cervical series with the exception of the atlas and axis, dorsal vertebrae with thoracic ribs, partial limbs and some sacral vertebrae.[7]

In 2001, the paleontologists James M. Clark, Mark A. Norell and Rinchen Barsbold named the new genus and type species Citipati osmolskae based on the now regarded holotype IGM 100/978, and referred specimens IGM 100/971 (embryo) with 100/979 ("Big Mama"). The generic name, Citipati, is formed from the Sanskrit words citi (meaning funeral pyre) and pati (meaning lord) in reference to the lord of cemeteries in the Tibetan Buddhism folklore, Citipati, which is often depicted as a humanoid skeleton. The specific name, osmolskae, is in honor to the noted Polish paleontologist Halszka Osmólska, whose work dealt extensively with Mongolian theropods.[8]

Description of specimens

Though the first specimen of Citipati (IGM 100/971) was briefly reported and discussed, Norell and colleagues in 2001 provided an extensive description of this specimen. As the description was published prior to the formal naming of Citipati, Norell and team tentatively referred this small embryo to a "new large species from Ukhaa Tolgod"—in fact, later known as Citipati osmolskae—based on the shared tall premaxilla morphology among specimens.[9] The more famous IGM 100/979 was extensively described by Clark and team in 1999, also prior to the naming of Citipati. They considered this specimen to be most similar and closely related to Oviraptor than to the other oviraptorids known at that time.[10] Despite being discovered in 1995, the specimen IGM 100/1004 remained partially figured and largely undescribed for years until its formal referral to the taxon Citipati osmolskae in 2018 by Norell and team.[7]

The largest and most complete specimen of Citipati is represented by the holotype IGM 100/978, however, it was preliminarily described and figured in 2001 during the naming of the taxon and during that time, the specimen had not been completely prepared.[8] The skull anatomy of the specimen was later described by Clark and colleagues in 2002,[11] the furcula morphology in 2009 by Sterling J. Nesbitt with team,[12] and the caudal vertebrae by W. Scott Persons and colleagues in 2014 who noted the presence of a pygostyle.[13] Subsequent descriptions have been published in 2018 by Norell and team describing and illustrating some cervical vertebrae and uncinate processes,[7] and Amy M. Balanoff and colleagues describing the endocranium anatomy.[14] In 2003 Amy Davidson described the process in which the holotype was prepared,[15] later supplemental by Christina Bisulca and team in 2009 describing conservation treatments of broken bones.[16]

Zamyn Khondt oviraptorid

The Zamyn Khondt oviraptorid is a well-known oviraptorid represented by a single and rather complete specimen (IGM 100/42) collected from the Zamyn Khondt (also spelled as Dzamin Khond) locality of the Djadokhta Formation. Since the type skull and body remains of Oviraptor are crushed and partially preserved, the Zamyn Khondt oviraptorid had become the quintessential depiction of the former, even appearing in scientific literature with the label Oviraptor philoceratops.[17]

Clark with team have pointed out that this distinctive-looking, tall-crested oviraptorid has more features of the skull in common with Citipati than it does with Oviraptor. Though being different in the crest shape of the skull, the Zamyn Khondt oviraptorid is similar to Citipati in the shape of the narial region and premaxilla morphology. They considered this oviraptorid to belong to the genus, however, they could neither confirm nor disregard that this specimen represents a second species of Citipati.[8][11] Lü Junchang and colleagues in 2004 found this specimen to be closely related to Oviraptor,[18] Phil Senter with team in 2007 placed it close to neither genus,[19] and in 2020 Gregory F. Funston and colleagues found it to be the sister taxon of Citipati.[20]

Description

Citipati was a large-bodied oviraptorid, with the largest individuals being emu-sized animals; it has been estimated at 2.5–2.9 m (8.2–9.5 ft) in length with a weight between 75–110 kg (165–243 lb),[21][22][23] and was one of the largest known oviraptorosaurs until the description of Gigantoraptor.[24] Based on their humeral lengths, IGM 100/1004 was about 11% larger than IGM 100/979.[7] Like other oviraptorids, Citipati had an unusually long neck and shortened tail compared to most other theropods. The presence of a pygostyle and the brooding pose in specimens of Citipati indicate the presence of large wing and tail feathers, and plumage. Other oviraptorids and oviraptorosaurs are also known to have been feathered.[13][7]

Skull

Its skull was unusually short and highly pneumatized (riddled with air-spaced openings), ending in a stout, toothless beak. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Citipati was its tall crest, superficially similar to that of a modern cassowary. The crest was relatively low in C. osmolskae formed by the premaxilla and nasal bones of the skull, with a nearly vertical front margin grading into the beak. In contrast, the crest of IGM 100/42 was taller with a prominent notch in the front margin, creating a squared appearance.[11]

Classification

Citipati is often referred to the subfamily Oviraptorinae along with Oviraptor. However, in 2020, Gregory F. Funston and colleagues found Oviraptor to be more basal, so they named a new subfamily Citipatiinae. The cladogram below follows their analysis:[20]

| Oviraptoridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Feeding mechanics

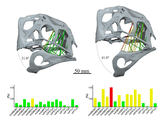

A 2022 study of the bite force of Citipati and comparisons with other oviraptorosaurs such as Incisivosaurus, Khaan, and Conchoraptor suggests that Citipati had a very strong bite force, scored between 349.3 N and 499.0 N. The moderate jaw gape seen in oviraptorosaurs is indicative of herbivory in the majority of the group, but it is clear they were likely feeding on much tougher vegetation than other herbivorous theropods in their environment, such as ornithomimosaurs and therizinosaurs were able to. The examinations suggest oviraptorosaurs may have been powerful-biting generalists or specialists that partook of niche partitioning both in body size and jaw function. Of the oviraptorids examined in this study, Citipati had one of the most powerful bites, but its biting mechanics were unique among the oviraptorosaurs investigated.[25]

Reproduction

The embryo-bearing egg was otherwise identical to other oviraptorid eggs in shell structure and was found in an isolated nest, again arranged in a circular pattern. Two skulls belonging to very young or embryonic Byronosaurus were found associated with the same nest as the first Citipati embryo. It is possible that these tiny troodontids were preyed upon by the Citipati to feed its nest. Alternately, Mark Norell suggested that the juvenile troodonts were raiding the Citipati nest, or even that an adult Byronosaurus had laid eggs in a Citipati nest as an act of nest parasitism.[1][2]

Although fossilized dinosaur eggs are rare, Citipati eggs and oviraptorid eggs in general, are relatively well known. Along with the two known nesting specimens, dozens of isolated oviraptorid nests have been uncovered in the Gobi Desert. Citipati eggs are elongatoolithid, which are shaped like elongated ovals and resemble the eggs of ratites in texture and shell structure. In the nest, Citipati eggs are typically arranged in concentric circles of up to three layers, and a complete clutch may have consisted of as many of 22 eggs.[26] The eggs of Citipati are the largest known definitive oviraptorid eggs, at 18 cm. In contrast, eggs associated with Oviraptor are only up to 14 cm long.[10]

The two nesting specimens of Citipati are situated on top of egg clutches, with their limbs spread symmetrically on each side of the nest, front limbs covering the nest perimeter. This brooding posture is found today only in birds and supports a behavioral link between birds and theropod dinosaurs.[10] The nesting position of Citipati also supports the hypothesis that it and other oviraptorids had feathered forelimbs. Thomas P. Hopp and Mark J. Orsen in 2004 analyzed the brooding behavior of extinct and extant dinosaur species, including oviraptorids, in order to evaluate the reason for the elongation and development of wing and tail feathers. Given that IGM 100/979 was found in a very avian-like posture, with the forelimbs in a near-folded posture and the pectoral region, belly, and feet in contact with the eggs, Hopp and Orsen indicated that long pennaceous feathers and a feather covering were most likely present in life. The "wings" and tail of oviraptorids would have granted protection for the eggs and hatchlings against climate factors like the sunlight, wind, and rainfalls. However, the arms of this specimen were not extremely folded as in some modern birds, instead, they are more extended resembling the style of large flightless birds like the ostrich. The extended position of the arm is also similar to the brooding behavior of this bird, which is known to nest in large clutches like oviraptorids. Based on the forelimb position of nesting oviraptorids, Hopp and Orsen proposed brooding as the ancestral reason behind wing and tail feather elongation, as there was a greater need to provide optimal protection for eggs and juveniles.[27]

In 2014, W. Scott Persons and colleagues suggested that oviraptorosaurs were secondarily flightless and several of the traits in their tails may indicate a propensity for display behaviour, such as courtship display. The tail of several oviraptorosaurs and oviraptorids ended in pygostyles, a bony structure at the end of the tail that, at least in modern birds, is used to support a feather fan. Furthermore, the tail was notably muscular and had a pronounced flexibility, which may have aided in courtship movements.[13]

Paleopathology

Clark and colleagues in 1999 during the description of "Big Mama" noted that the right ulna was badly broken but healed, leaving a prominent callus and possible elongated groove over the injury.[10] As the ulna features positive signs of healing, in 2019 Leas Hearn and team suggested that this individual managed to survive an injury that would have interfered with foraging for several weeks in order to lay and incubate its nest.[28]

In 2002 Clark with team reported a small notch preserved on the right jugal, just beneath the orbit, of the holotype skull of Citipati. This anomaly was likely produced by external damage, leaving a small injury.[11]

Paleoenvironment

Citipati is vastly known from the Ukhaa Tolgod locality of the Djadokhta Formation, which is dated around 71 million to 75 million years ago (Late Cretaceous).[29] This formation is separated into a lower Bayn Dzak Member and upper Turgrugyin Member, of which the Ukhaa Tolgod locality belongs to the former. Characteristic lithology across the formation include reddish-orange and pale orange to light gray, medium to fine-grained sands and sandstones, and caliche, with better exposures represented at Ukhaa Tolgod. The settings in which Citipati and associated paleofauna lived are interpreted as large dune fields/sand dunes and several short-lived water bodies with arid to semiarid climates.[29][30] Other dinosaurs known from Ukhaa Tolgod include alvarezsaurids Kol and Shuvuuia;[31][32] ankylosaurid Minotaurasaurus;[33] birds Apsaravis and Gobipteryx;[34][35] dromaeosaurid Tsaagan;[36] fellow oviraptorid Khaan;[37] troodontids Almas and Byronosaurus;[38][39] and an undescribed protoceratopsid closely related to Protoceratops.[40]

See also

References

- ^ a b Norell, M. A.; Clark, J. M.; Dashzeveg, D.; Barsbold, R.; Chiappe, L. M.; Davidson, A. R.; McKenna, M. C.; Altangerel, P.; Novacek, M. J. (1994). "A theropod dinosaur embryo and the affinities of the Flaming Cliffs Dinosaur eggs". Science. 266 (5186): 779–782. Bibcode:1994Sci...266..779N. doi:10.1126/science.266.5186.779. JSTOR 2885545. PMID 17730398. S2CID 22333224.

- ^ a b Bever, G. S.; Norell, M. A. (2009). "The Perinate Skull of Byronosaurus (Troodontidae) with Observations on the Cranial Ontogeny of Paravian Theropods". American Museum Novitates (3657): 1–52. doi:10.1206/650.1. hdl:2246/5980.

- ^ Norell, M. A.; Clark, J. M.; Chiappe, L. M.; Dashzeveg, D. (1995). "A nesting dinosaur". Nature. 378 (6559): 774–776. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..774N. doi:10.1038/378774a0. S2CID 4245228.

- ^ Wildford, J. N. (1995). "Fossil of Nesting Dinosaur Strengthens Link to Modern Birds". The New York Times (National ed.). p. 22.

- ^ a b Webster, D. (1996). "Dinosaurs of the Gobi: Unearthing a Fossil Trove". National Geographic. Vol. 190, no. 1. pp. 70–89.

- ^ Clark, J. M. (1995). "An egg thief exonerated". Natural History. 104 (6): 56.

- ^ a b c d e Norell, M. A.; Balanoff, A. M.; Barta, D. E.; Erickson, G. M. (2018). "A second specimen of Citipati osmolskae associated with a nest of eggs from Ukhaa Tolgod, Omnogov Aimag, Mongolia". American Museum Novitates (3899): 1–44. doi:10.1206/3899.1. hdl:2246/6858. S2CID 53057001.

- ^ a b c Clark, J. M.; Norell, M. A.; Barsbold, R. (2001). "Two new oviraptorids (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous Djadokta Formation, Ukhaa Tolgod". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (2): 209–213. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0209:TNOTOU]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 20061948. S2CID 86076568.

- ^ Norell, M. A.; Clark, J. M.; Chiappe, L. M. (2001). "An Embryonic Oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". American Museum Novitates (3315): 1–17. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2001)315<0001:AEODTF>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2931. S2CID 51731173.

- ^ a b c d Clark, J. M.; Norell, M. A.; Chiappe, L. M. (1999). "An oviraptorid skeleton from the Late Cretaceous of Ukhaa Tolgod, Mongolia, preserved in an avianlike brooding position over an oviraptorid nest". American Museum Novitates (3265): 1–36. hdl:2246/3102.

- ^ a b c d Clark, J. M.; Norell, M. A.; Rowe, T. (2002). "Cranial Anatomy of Citipati osmolskae (Theropoda, Oviraptorosauria), and a Reinterpretation of the Holotype of Oviraptor philoceratops" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3364): 1–24. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2002)364<0001:CAOCOT>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2853. S2CID 52247789.

- ^ Nesbitt, S. J.; Turner, A. H.; Spaulding, M.; Conrad, J. L.; Norell, M. A. (2009). "The theropod furcula". Journal of Morphology. 270 (7): 856–879. doi:10.1002/jmor.10724. PMID 19206153.

- ^ a b c Persons, W. S.; Currie, P. J.; Norell, M. A. (2014). "Oviraptorosaur tail forms and functions". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0093.

- ^ Balanoff, A. M.; Norell, M. A.; Hogan, A. V. C.; Bever, G. S. (2018). "The Endocranial Cavity of Oviraptorosaur Dinosaurs and the Increasingly Complex, Deep History of the Avian Brain". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 91 (3): 125–135. doi:10.1159/000488890. PMID 30099460. S2CID 51967993.

- ^ Davidson, A. (2003). "Preparation of a fossil dinosaur" (PDF). Objects Specialty Group Postprints. 10: 49−61. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Bisulca, C.; Elkin, L. K.; Davidson, A. (2009). "Consolidation of Fragile Fossil Bone From Ukhaa Tolgod, Mongolia (Late Cretaceous) With Conservare OH100". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 48 (1): 37−50. doi:10.1179/019713609804528098. JSTOR 27784651. S2CID 140672498.

- ^ Barsbold, R.; Maryańska, T.; Osmólska, H. (1990). "Oviraptorosauria". In Weishampel, D. B.; Osmolska, H.; Dodson, P. (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 249−258. ISBN 9780520067271.

- ^ Lü, J.; Tomida, Y.; Azuma, Yoichi; Dong, Z.; Lee, Y. (2004). "New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia". Bulletin of the National Science Museum. Series C, Geology & Ppaleontology. S2CID 55280873.

- ^ Senter, P. (2007). "A new look at the phylogeny of coelurosauria (Dlnosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (4): 429–463. Bibcode:2007JSPal...5..429S. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002143. S2CID 83726237.

- ^ a b Funston, G. F.; Tsogtbaatar, C.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Sullivan, C.; Currie, P. J. (2020). "A new two-fingered dinosaur sheds light on the radiation of Oviraptorosauria". Royal Society Open Science. 7 (10): 201184. Bibcode:2020RSOS....701184F. doi:10.1098/rsos.201184. PMC 7657903. PMID 33204472.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 153.

- ^ Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2016). Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos. Spain: Larousse. p. 272.

- ^ Pintore, R.; Hutchinson, J. R.; Bishop, P. J.; Tsai, H. P.; Houssaye, A. (2024). "The evolution of femoral morphology in giant non-avian theropod dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 50 (2): 308–329. Bibcode:2024Pbio...50..308P. doi:10.1017/pab.2024.6. PMC 7616063. PMID 38846629.

- ^ Xing, X.; Tan, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tan, L. (2007). "A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of China". Nature. 447 (7146): 844–847. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..844X. doi:10.1038/nature05849. PMID 17565365. S2CID 6649123. Supplementary Information

- ^ Meade, Luke E.; Ma, Waisum (2022). "Cranial muscle reconstructions quantify adaptation for high bite forces in Oviraptorosauria". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 3010. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.3010M. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-06910-4. PMC 8863891. PMID 35194096.

- ^ Varricchio, D.J. (2000). "Reproduction and Parenting," in Paul, G.S. (ed.). The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 279–293.

- ^ Hopp, T. P.; Orsen, M. J. (2004). "Dinosaur Brooding Behavior and the Origin of Flight Feathers" (PDF). In Currie, P. J.; Koppelhus, E. B.; Shugar, M. A.; Wright, J. L. (eds.). Feathered dragons: studies on the transition from dinosaurs to birds. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 234–250.

- ^ Hearn, L.; Amanda, X.; Williams, C. (2020). "Pain in dinosaurs: what is the evidence?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 374 (1785). doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0370. PMC 6790383. PMID 31544618.

- ^ a b Dashzeveg, D.; Dingus, L.; Loope, D. B.; Swisher III, C. C.; Dulam, T.; Sweeney, M. R. (2005). "New Stratigraphic Subdivision, Depositional Environment, and Age Estimate for the Upper Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation, Southern Ulan Nur Basin, Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3498): 1−31. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2005)498[0001:NSSDEA]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5667. S2CID 55836458.

- ^ Dingus, L.; Loope, D. B.; Dashzeveg, D.; Swisher III, C. C.; Minjin, C.; Novacek, M. J.; Norell, M. A. (2008). "The Geology of Ukhaa Tolgod (Djadokhta Formation, Upper Cretaceous, Nemegt Basin, Mongolia)". American Museum Novitates (3616): 1−40. doi:10.1206/442.1. hdl:2246/5916. S2CID 129735494.

- ^ Suzuki, S.; Chiappe, L. M.; Dyke, G. J.; Watabe, M.; Barsbold, R.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (2002). "A New Specimen of Shuvuuia deserti Chiappe et al., 1998, from the Mongolian Late Cretaceous with a Discussion of the Relationships of Alvarezsaurids to Other Theropod Dinosaurs". Contributions in Science. 494: 1−18. doi:10.5962/p.226791. S2CID 135344028.

- ^ Turner, A. H.; Nesbitt, S. J.; Norell, M. A. (2009). "A Large Alvarezsaurid from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3648): 1–14. doi:10.1206/639.1. hdl:2246/5967. S2CID 59459861.

- ^ Alicea, J.; Loewen, M. (2013). "New Minotaurasaurus material from the Djodokta Formation establishes new taxonomic and stratigraphic criteria for the taxon". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Program and Abstracts: 76. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Chiappe, L. M.; Norell, M. A.; Clark, J. (2001). "A New Skull of Gobipteryx minuta (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3346): 1−15. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2001)346<0001:ANSOGM>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2899. S2CID 51857603..

- ^ Clarke, J. A.; Norell, M. A. (2002). "The Morphology and Phylogenetic Position of Apsaravis ukhaana from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3387): 1−46. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2002)387<0001:TMAPPO>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2876. S2CID 52971055.

- ^ Norell, M. A.; Clark, J. M.; Turner, A. H.; Makovicky, P. J.; Barsbold, R.; Rowe, T. (2006). "A New Dromaeosaurid Theropod from Ukhaa Tolgod (Ömnögov, Mongolia)". American Museum Novitates (3545): 1–51. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2006)3545[1:ANDTFU]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5823.

- ^ Clark, J. M.; Norell, M. A.; Barsbold, R. (2001). "Two new oviraptorids (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous Djadokta Formation, Ukhaa Tolgod". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (2): 209–213. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0209:TNOTOU]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 20061948. S2CID 86076568.

- ^ Makovicky, P. J.; Norell, M. A.; Clark, J. M.; Rowe, T. E. (2003). "Osteology and Relationships of Byronosaurus jaffei (Theropoda: Troodontidae)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3402): 1–32. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2003)402<0001:oarobj>2.0.co;2. hdl:2246/2828. S2CID 51824767.

- ^ Pei, R.; Norell, M. A.; Barta, D. E; Bever, G. S.; Pittman, M.; Xu, X. (2017). "Osteology of a New Late Cretaceous Troodontid Specimen from Ukhaa Tolgod, Ömnögovi Aimag, Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3889): 1–47. doi:10.1206/3889.1. hdl:2246/6818. S2CID 90883541.

- ^ Prieto-Márquez, A.; Garcia-Porta, J.; Joshi, S. H.; Norell, M. A.; Makovicky, P. J. (2020). "Modularity and heterochrony in the evolution of the ceratopsian dinosaur frill". Ecology and Evolution. 10 (13): 6288–6309. Bibcode:2020EcoEv..10.6288P. doi:10.1002/ece3.6361. PMC 7381594. PMID 32724514.

External links

Media related to Citipati at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Citipati at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Citipati at Wikispecies

Data related to Citipati at Wikispecies- Interactive CT scan of the holotype Citipati skull at DigiMorph

- 3D model of the holotype Citipati skull at Sketchfab