Christianity in the 14th century

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The 14th century saw major developments in Christianity, including the Western Schism, the decline of the Crusades, and the appearance of precursors to Protestantism.

Inquisition

King Philip IV of France created an inquisition for his suppression of the Knights Templar during the 14th century.[1] King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella formed another in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted ex-Jewish and ex-Muslim converts.[2] Over a 350-year period, this Spanish Inquisition executed between 3,000 and 4,000 people,[3] representing around two percent of those accused.[4] The inquisition played a major role in the final expulsion of Islam from the kingdoms of Sicily and Spain.[5] In 1482, Pope Sixtus IV condemned its excesses but Ferdinand ignored his protests.[6] Historians note that for centuries Protestant propaganda and popular literature exaggerated the horrors of these inquisitions.[1][7][8][9] According to Edward Norman, this view "identified the entire Catholic Church ... with [the] occasional excesses" wrought by secular rulers.[1]

Western Schism

The Western Schism, or Papal Schism, was a prolonged period of crisis in Latin Christendom from 1378 to 1416, when there were two or more claimants to the See of Rome and there was conflict concerning the rightful holder of the papacy. The conflict was political, rather than doctrinal, in nature.

To escape instability in Rome, Clement V in 1309 became the first of seven popes to reside in the fortified city of Avignon in southern France[10] during a period known as the Avignon Papacy. For 69 years popes resided in Avignon rather than Rome. This was not only an obvious source of not only confusion but of political animosity as the prestige and influence of the city of Rome waned without a resident pontiff. The papacy returned to Rome in 1378 at the urging of Catherine of Siena and others who felt the See of Peter should be in the Roman church.[11][12] Though Pope Gregory XI, a Frenchman, returned to Rome in 1378, the strife between Italian and French factions intensified, especially following his subsequent death.

In 1378 the conclave elected an Italian from Naples, Pope Urban VI; his intransigence in office soon alienated the French cardinals, who withdrew to a conclave of their own, asserting the previous election was invalid since its decision had been made under the duress of a riotous mob. They elected one of their own, Robert of Geneva, who took the name Pope Clement VII. By 1379, he was back in the palace of popes in Avignon, while Urban VI remained in Rome.

For nearly forty years, there were two papal curias and two sets of cardinals, each electing a new pope for Rome or Avignon when death created a vacancy. Efforts at resolution further complicated the issue when a third compromise pope was elected in 1409.[13] The matter was finally resolved in 1417 at the Council of Constance where the cardinals called upon all three claimants to the papal throne to resign and held a new election naming Martin V pope.[13]

Western theology

Scholastic theology continued to develop as the 13th century gave way to the fourteenth, becoming ever more complex and subtle in its distinctions and arguments. There was a rise to dominance of the nominalist or voluntarist theologies of men like William of Ockham. The 14th century was also a time in which movements of widely varying character worked for the reform of the institutional church, such as conciliarism and Lollardy. Spiritual movements such as the Devotio Moderna also flourished.

Notable authors include:

- Duns Scotus (1266-1308)

- Ramon Lull (1232-1315)

- Giles of Rome (1243-1316)

- Dante Alighieri (1265-1321)

- Meister Eckhart (1260-1327)

- Peter Auriol (1280-1322)

- Marsilius of Padua (1275-1342)

- Nicholas of Lyra (1270-1349)

- Thomas Bradwardine (1290-1349)

- William of Ockham (1287-1347)

- Richard Rolle (1290-1349)

- Gregory of Rimini (1300-1358)

- Jean Buridan (1300-1358)

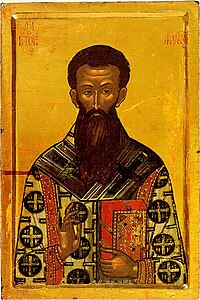

- Gregory Palamas (1296-1359)

- Johannes Tauler (1300-1361)

- Theologia Germanica (anonymous- but often attributed to Tauler)

- Henry Suso (1295-1366)

- John of Ruysbroeck (1293-1381)

- Nicole Oresme (1320-1382)

- John Wycliffe (1320-1384)

- Geert Groote (1340-1384)

- Catherine of Siena (1347-1380)

- Walter Hilton (1340-1396)

- The Cloud of Unknowing (anonymous - but often attributed to Hilton)

- The Book of Privy Counseling (anonymous - but often attributed to Hilton)

- Julian of Norwich (1342-1416)

Hesychast Controversy

Under church tradition the practice of Hesychasm has it beginnings in the bible, Matthew 6:6 and the Philokalia. The tradition of contemplation with inner silence or tranquility is shared by all Eastern ascetics having its roots in the Egyptian traditions of monasticism exemplified by such Orthodox monastics as St Anthony of Egypt.

About the year 1337 Hesychasm attracted the attention of a learned member of the Orthodox Church, Barlaam, a Calabrian monk who at that time held the office of abbot in the Monastery of St Saviour's in Constantinople and who visited Mount Athos. Mount Athos was at the height of its fame and influence under the reign of Andronicus III Palaeologus and under the 'first-ship' of the Protos Symeon. On Mount Athos, Barlaam encountered Hesychasts and heard descriptions of their practices, also reading the writings of the teacher in Hesychasm of St Gregory Palamas, an Athonite monk.

Trained in Western scholastic theology, Barlaam was scandalised by Hesychasm and began to combat it both orally and in his writings. As a private teacher of theology in the Western Scholastic mode, Barlaam propounded a more intellectual and propositional approach to the knowledge of God than the Hesychasts taught. Barlaam took exception to, as heretical and blasphemous, the doctrine entertained by the Hesychasts as to the nature of the uncreated light, the experience of which was said to be the goal of Hesychast practice. It was maintained by the Hesychasts to be of divine origin and to be identical to that light which had been manifested to Jesus' disciples on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration. This Barlaam held to be polytheistic, inasmuch as it postulated two eternal substances, a visible (immanent) and an invisible God (transcendent).

On the Hesychast side, the controversy was taken up by St Gregory Palamas, afterwards Archbishop of Thessalonica, who was asked by his fellow monks on Mt Athos to defend Hesychasm from the Barlaam's attacks. St Gregory was well-educated in Greek philosophy (dialectical method) and thus able to defend Hesychasm using Western precepts. In the 1340s, he defended Hesychasm at three different synods in Constantinople and also wrote a number of works in its defense.

In 1341 the dispute came before a synod held at Constantinople and was presided over by the Emperor Andronicus. The synod, taking into account the regard in which the writings of the pseudo-Dionysius were held, condemned Barlaam, who recanted and returned to Calabria, afterwards becoming a bishop in the Roman Catholic Church. One of Barlaam's friends, Gregory Akindynos, who originally was also a friend of St Gregory Palamas, took up the controversy, and three other synods on the subject were held, at the second of which the followers of Barlaam gained a brief victory. But in 1351 at a synod under the presidency of the Emperor John VI Cantacuzenus, Hesychast doctrine and Palamas' Essence-Energies distinction was established as the doctrine of the Orthodox Church.

Following the decision of 1351, there was strong repression against anti-Palamist thinkers. Kalekas reports on this repression as late as 1397, and for theologians in disagreement with Palamas, there was ultimately no choice but to emigrate and convert to Catholicism, a path taken by Kalekas as well as Demetrios Kydones and Ioannes Kypariossiotes. This exodus of highly educated Greek scholars, later reinforced by refugees following the Fall of Constantinople of 1453, had a significant influence on the first generation (that of Petrarch and Boccaccio) of the incipient Italian Renaissance.

The Roman Catholic Church has never fully accepted Hesychasm, especially the distinction between the energies or operations of God and the essence of God, and the notion that those energies or operations of God are uncreated.[14] In Roman Catholic theology as it has developed since the scholastic period, the essence of God can be known but only in the next life; the grace of God is always created; and the essence of God is pure act, so that there can be no distinction between the energies or operations and the essence of God (see, e.g., the Summa Theologiae of St Thomas Aquinas).[14] Some of these positions depend on Aristotelian metaphysics.

Contemporary historians Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos and Nicephorus Gregoras deal very copiously with this subject, taking the Hesychast and Barlaamite sides respectively. The Orthodox perspective is one that states that there is scientific knowledge based on demonstration and spiritual knowledge based on demonstration. That the two understandings must remain separate in order to have a proper understanding of both in order to reject dualism. The Eastern approach to understanding God and spiritual matters as one that should not be approached with a Scholastic and or dialectical method (philosophy).[15] Respected fathers of the church have held that these councils that agree that experiential prayer is Orthodox, refer to these as councils as Ecumenical Councils Eight and Nine.

Monasticism

Roman Catholic orders

Many distinct monastic orders developed within Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism.

- Bridgettines, founded c.1350

- Hieronymites, founded in Spain in 1364, an eremitic community formally known as the "Order of Saint Jerome"

Protestant monasticism

Monasticism in the Protestant tradition proceeds from John Wycliffe who organized the Lollard Preacher Order (the "Poor Priests") to promote his reformation views.[16]

Protestant Reformation precursors

Unrest because of the Western Schism excited wars between princes, uprisings among the peasants, and widespread concern over corruption in the Church. A new nationalism also challenged the relatively internationalist medieval world. The first of a series of disruptive and new perspectives came from John Wycliffe at Oxford University, then from Jan Hus at the University of Prague. The Catholic Church officially concluded this debate at the Council of Constance (1414–1417). The conclave condemned Jan Hus, who was executed by burning in spite of a promise of safe-conduct. At the command of Pope Martin V, Wycliffe was posthumously exhumed and burned as a heretic twelve years after his burial.

Crusade aftermath

The island of Ruad, three kilometers from the Syrian shore, was occupied by the Knights Templar but was ultimately lost to the Mamluks in the Fall of Ruad on September 26, 1302. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, which was not a crusader state and was not Latin Christian but was closely associated with the crusader states and was ruled by the Latin Christian Lusignan dynasty for its last 34 years, survived until 1375. Other echoes of the crusader states survived for longer, but well away from the Holy Land.

Crusade against the Tatars

In the 14th century, Khan Tokhtamysh combined the Blue and White Hordes forming the Golden Horde. It seemed that the power of the Golden Horde had begun to rise, but in 1389, Tokhtamysh made the disastrous decision of waging war on his former master Tamerlane. Tamerlane's hordes rampaged through southern Russia, crippling the Golden Horde's economy and practically wiping out its defenses in those lands.

After losing the war, Tokhtamysh was dethroned by the party of Khan Temur Kutlugh and Emir Edigu, supported by Tamerlane. When Tokhtamysh asked Vytautas the Great for assistance in retaking the Horde, the latter readily gathered a huge army which included Lithuanians, Ruthenians, Russians, Mongols, Moldavians, Poles, Romanians and Teutonic Knights.

In 1398, the huge army moved from Moldavia and conquered the southern steppe all the way to the Dnieper River and northern Crimea. Inspired by their great successes, Vytautas declared a Crusade against the Tatars with Pope Boniface IX backing him. Thus, in 1399, the army of Vytautas once again moved on the Horde. His army met the Horde's at the Vorskla River, slightly inside Lithuanian territory.

Although the Lithuanian army was well equipped with cannon, it could not resist a rear attack from Edigu's reserve units. Vytautas hardly escaped alive. Many princes of his kin—possibly as many as 20—were killed, and the victorious Tatars besieged Kiev. Meanwhile, Temur Kutlugh died from the wounds received in the battle, and Tokhtamysh was killed by one of his own men.

Alexandrian Crusade

The Alexandrian Crusade of October 1365 was a minor seaborne crusade against Muslim Alexandria led by Peter I of Cyprus. His motivation was at least as commercial as religious.

Politics and culture

The Crusades had an enormous influence on the European Middle Ages. At times, much of the continent was united under a powerful Papacy, but by the 14th century, the development of centralized bureaucracies (the foundation of the modern nation-state) was well on its way in France, England, Spain, Burgundy, and Portugal, and partly because of the dominance of the church at the beginning of the crusading era.

The military experiences of the crusades also had their effects in Europe; for example, European castles became massive stone structures as they were in the east, rather than smaller wooden buildings as they had typically been in the past.

In addition, the Crusades are seen as having opened up European culture to the world, especially Asia:

The Crusades brought about results of which the popes had never dreamed, and which were perhaps the most, important of all. They re-established traffic between the East and West, which, after having been suspended for several centuries, was then resumed with even greater energy; they were the means of bringing from the depths of their respective provinces and introducing into the most civilized Asiatic countries Western knights, to whom a new world was thus revealed, and who returned to their native land filled with novel ideas... If, indeed, the Christian civilization of Europe has become universal culture, in the highest sense, the glory redounds, in no small measure, to the Crusades."[17]

Along with trade, new scientific discoveries and inventions made their way east or west. Persian advances (including the development of algebra, optics, and refinement of engineering) made their way west and sped the course of advancement in European universities that led to the Renaissance in later centuries

The invasions of German crusaders prevented formation of the large Lithuanian state incorporating all Baltic nations and tribes. Lithuania was destined to become a small country and forced to expand to the East looking for resources to combat the crusaders.[18]

Trade

The need to raise, transport and supply large armies led to a flourishing of trade throughout Europe. Roads largely unused since the days of Rome had significant increases in traffic as local merchants began to expand their horizons. This was not only because the Crusades prepared Europe for travel, but also because many wanted to travel after being reacquainted with the products of the Middle East. This also aided in the beginning of the Renaissance in Italy, as various Italian city-states from the very beginning had important and profitable trading colonies in the crusader states, both in the Holy Land and later in captured Byzantine territory.

Increased trade brought many things to Europeans that were once unknown or extremely rare and costly. These goods included a variety of spices, ivory, jade, diamonds, improved glass-manufacturing techniques, early forms of gunpowder, oranges, apples, and other Asian crops, and many other products.

Serbian Church

The status of the Serbian Orthodox Church grew along with the expansion and heightened prestige of the Serbian kingdom. On April 16, 1346 (Easter), King Stefan Dušan of Serbia convoked a grand assembly at Skopje, attended by the Serbian Archbishop Joanikije II, Archbishop Nicholas I of Ohrid, Patriarch Simeon of Bulgaria and various religious leaders of Mount Athos. The assembly and clergy agreed on, and then ceremonially performed the raising of the autocephalous Serbian Archbishopric to the status of Patriarchate. The Archbishop was from now on titled Serbian Patriarch. The new Patriarch Joanikije II now solemnly crowned Stefan Dušan as "Emperor and autocrat of Serbs and Romans" (see Emperor of Serbs). The new Serbian Patriarchate took over supreme ecclesiastical jurisdiction over Mount Athos and many Greek eparchies in Aegean Macedonia that were until then under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[19] The same process continued after the Serbian conquests of Thessaly, Epirus, Aetolia and Acarnania in 1347 and 1348.[20] In the same time, the Ohrid Archbishopric remained autocephalous, recognizing the honorary primacy of the new Serbian Patriarchate.

Since proclamation of the Patriarchate was performed without consent of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, various canonical and political questions were raised. Supported by the Byzantine government, Ecumenical Patriarch Callistus I of Constantinople issued an act of condemnation and excommunication of Tsar Stefan Dušan and Serbian Patriarch Joanikije in 1350.[21] That act created a rift between the Byzantine and Serbian churches, but not on dogmatic grounds, since the dispute was limited to the questions of ecclesiastical order and jurisdiction. Serbian Patriarch Joanikije died in 1354, and his successor Patriarch Sava IV (1354-1375) faced new challenges in 1371, when Turks defeated the Serbian army in the Battle of Marica and started their expansion into Serbian lands.[22] Since they were facing the common enemy, the Serbian and Byzantine governments and church leaders reached an agreement in 1375.[23] The act of excommunication was revoked and the Serbian Church was recognized as a Patriarchate, under the condition of returning all eparchies in contested southern regions to the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[24][25]

After the new and decisive defeat by the Turks in the famous Battle of Kosovo in 1389, Serbia became a tributary state to the Ottoman Empire, and the Serbian Patriarchate was also affected by general social decline, since Ottoman Turks continued their expansion and raids into Serbian lands, devastating many monasteries and churches.[26] The city of Skopje was taken by Turks in 1392, and all other southern regions were taken in 1395.[27] That led to the gradual retreat of the jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate in the south and expansion of the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Ohrid.

Spread of Christianity

Lithuania

Lithuania and Samogitia were ultimately Christianized from 1386 until 1417 by the initiative of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Jogaila and his cousin Vytautas.

Timeline

- 1304-1321 Divine Comedy (Divina Commedia), by Dante Alighieri; most consensual dates are: Inferno written between 1304 and 1307-1308, Purgatorio from 1307-1308 to 1313-1314 and last the Paradiso from 1313-1314 to 1321 (year of Dante's death).

- 1303 - Arnold of Cologne arrives in China to assist Giovanni di Monte Corvino[28]

- 1305-1378 Avignon Papacy, Popes reside in Avignon, France

- 1311-1312 Catholic Council of Vienne, disbanded Knights Templar

- 1314 Jacques de Molay, last Grandmaster of Knights Templar, burned at the stake

- 1321 - Jordanus, a Dominican friar, arrives in India as the first resident Roman Catholic missionary[29]

- 1322 - Odoric of Pordenone, a Franciscan friar from Italy, arrives in China

- 1323 - Franciscans make contacts on Sumatra, Java, and Borneo[30]

- 1326 - Chaghatayid Khan Ilchigedai grants permission for a church to be built in Samarkand, Uzbekistan [2]

- 1326 Metropolitan Peter moves his see from Kiev to Moscow

- 1334 - Chaghatayid Khan Buzun allows Christians to rebuild churches and permits Franciscans to establish a missionary episcopate in Almaliq, Azerbaijan [3]

- 1341-1351 Orthodox Fifth Council of Constantinople

- 1345 Sergii Radonezhskii founds a hermitage in the woods, which would grow into the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra

- 1368 - Collapse of the Franciscan mission in China as Ming Dynasty abolishes Christianity

- 1378-1418 Western Schism in Roman Catholicism

- 1379 - Stephen of Perm travels north toward the White Sea and settles as a missionary among the Uralic-speaking Komi peoples living between Pechora and Vychegda Rivers at Ust-Vim[31]

- 1380-1382 Wycliffe's Bible, by John Wycliffe, eminent theologian at Oxford, NT in 1380, OT (with help of Nicholas of Hereford) in 1382, translations into Middle English, 1st complete translation to English, included deuterocanonical books, preached against abuses, expressed anti-catholic views of the sacraments (Penance and Eucharist), the use of relics, and Clerical celibacy

- 1382 - Bible translated into English from Latin by John Wycliff[32]

- 1386 - Jogaila (baptized - Wladyslaw II), king of the Lithuanians, is baptized[30]

- 1389 - Large numbers of Christians march through the streets of Cairo, denouncing Islam and lamenting that they had abandoned the religion of their fathers from fear of persecution. They were beheaded, both men and women, and a fresh persecution of Christians followed[33]

- 1400 - Scriptures translated into Icelandic[30]

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Christian theology#Late Scholasticism and its contemporaries

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- Christianization

- Timeline of Christianity#Middle Ages

- Timeline of Christian missions#Middle Ages

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#800–1453

- Chronological list of saints and blesseds in the 14th century

References

- ^ a b c Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), p. 93

- ^ Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition (1997), pp. 48-49

- ^ Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages (2005), pp.150-152

- ^ Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition (1997), pp. 59, 203

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (1990), p.187

- ^ Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition (1997), p.49

- ^ Armstrong, The European Reformation (2002), p. 103

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (1990), p. 215

- ^ Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages (2005), p. 146

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), p. 122

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (1990), p. 232, Chapter 6 Christian Civilization by Colin Morris (University of Southampton)

- ^ Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages (2005), p. 155

- ^ a b McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (1990), p. 240, Chapter 7 The Late Medieval Church and its Reformation by Patrick Collinson (University of Cambridge)

- ^ a b "Catholic Culture: Library: Eastern Theology Has Enriched the Whole Church". Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ University of Athens - Department of Theology Archived 2008-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lawrence, C. H. Medieval Monasticism. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. ISBN 0-582-40427-4

- ^ Crusades in The New Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966, Vol. IV, p. 508.[1] Archived 2014-09-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Lithuanian) Tomas Baranauskas. Prūsų sukilimas—prarasta galimybė sukurti kitokią Lietuvą (Prussian rebellion—the lost chance of creating different Lithuania). 20 September, 2006 Archived 2009-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 323.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 65.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 310.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 97.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1956, pp. 485.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, pp. 9–10, 17.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 412.

- ^ Anderson, p. 334

- ^ Herbermann, p. 683

- ^ a b c Barrett, p. 25

- ^ Anderson, 639

- ^ Glazier, p. 82

- ^ Latourette, 1953, p. 611

Works cited

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850654773.

Further reading

- Esler, Philip F. The Early Christian World. Routledge (2004). ISBN 0-415-33312-1.

- Fletcher, Richard, The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD. London 1997.

- Freedman, David Noel (Ed). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (2000). ISBN 0-8028-2400-5.

- Padberg, Lutz v., (1998): Die Christianisierung Europas im Mittelalter, Stuttgart, Reclam (German)

- Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan. The Christian Tradition: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). University of Chicago Press (1975). ISBN 0-226-65371-4.