Chimney sweep

A chimney sweep is a person who inspects then clears soot and creosote from chimneys. The chimney uses the pressure difference caused by a hot column of gas to create a draught and draw air over the hot coals or wood enabling continued combustion. Chimneys may be straight or contain many changes of direction. During normal operation, a layer of creosote builds up on the inside of the chimney, restricting the flow. The creosote can also catch fire, setting the chimney (and potentially the entire building) alight. The chimney must be swept to remove the soot.

In Great Britain, master sweeps took apprentices, typically workhouse or orphan boys, and trained them to climb chimneys. In the German States, master sweeps belonged to trade guilds[1] and did not use climbing boys. In Italy, Belgium, and France climbing boys were used.

The occupation requires some dexterity, and carries health risks.[2]

History

The Tudors in England had established the risk of chimneys and an ordinance was created in 1582 both controlling materials (brick and stone rather than plastered timber) and requiring chimneys to be swept four times per year to prevent the build-up of soot (which is highly flammable). Any chimney fire could result in the owner being fined 3 shillings and 4 pence.[3]

With the increased urban population that came with the age of industrialisation, the number of houses with chimneys grew apace and the services of the chimney sweep became much sought-after.

Buildings were higher than before and the new chimneys' tops were grouped together.[4] The routes of flues from individual grates could involve two or more right angles and horizontal angled and vertical sections. The flues were made narrow to create a better draught, 14in by 9in (36 × 23 cm) being a common standard. Buckingham Palace had one flue with 15 angles, with the flue narrowing to 9in by 9in (23 × 23 cm).[5] Chimney sweeping was one of the more difficult, hazardous, and low-paying occupations of the era, and consequently has been derided in verse, ballad, and pantomime.

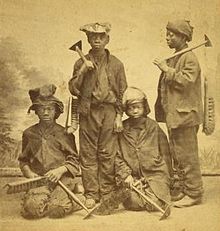

The first mechanical sweeper was invented by George Smart in 1803 but was resisted in the UK and the US. Joseph Glass marketed an improved sweeping machine in 1828; he is credited with being the inventor of the modern chimney sweep's brush.[6] In the northern US, whites gave up the trade and employed black sweep-boys from the South.[7] After regulation finally took hold in 1875 in the UK and the turn of the century in the US, the occupation became romanticized in popular media.

Great Britain

A boy 'stuck' to the right.

Boys as young as four climbed hot flues that could be as narrow as 81 square inches (9 × 9 inches or 23 × 23 cm). Work was dangerous and they could get jammed in the flue, suffocate or burn to death. As soot is carcinogenic, and as the boys slept under the soot sacks and were rarely washed, they were prone to chimney sweeps' carcinoma. From 1775 onward, there was increasing concern for the welfare of the boys, and Acts of Parliament were passed to restrict, and in 1875 to stop this usage.[8] Lord Shaftesbury, the philanthropist, led the later campaign.

Chimneys started to appear in Britain around 1200 (with the oldest extant example of a chimney in Britain being in the keep of Conisbrough Castle in Yorkshire, dating from 1185 AD[9]), when they replaced the open fire burning in the middle of the one room house. At first there would be one heated room in the building and chimneys would be large. Over the next four hundred years, rooms became specialized and smaller and many were heated. Sea coal started to replace wood, and it deposited a layer of flammable creosote in the inside surface of the flue, and caked it with soot. Whereas before, the chimney was a vent for the smoke, now the plume of hot gas was used to suck air into the fire, and this required narrower flues.[10] Even so, boys rarely climbed chimneys before the Great Fire of London, when building regulations were put in place and the design of chimneys was altered. The new chimneys were often angular and narrow, and the usual dimension of the flue in domestic properties was 9 inches (23 cm) by 14 inches (36 cm). The master sweep was unable to climb into such small spaces himself and employed climbing boys to go up the chimneys to dislodge the soot. The boys often 'buffed it', that is, climbed naked,[11] propelling themselves by their knees and elbows which were scraped raw. They were often put up hot chimneys, and sometimes up chimneys that were alight in order to extinguish the fire. Chimneys with sharp angles posed a particular hazard.[12] These boys were apprenticed to the sweep, and from 1778 until 1875 a series of laws attempted to regulate their working conditions, and many firsthand accounts were documented and published in parliamentary reports. From about 1803, there was an alternative method of brushing chimneys, but sweeps and their clients resisted the change, preferring climbing boys to the new humane sweeping machines.[13] Compulsory education was established in 1870 by the Elementary Education Act 1870 but it was a further five years before legislation was put in place to license chimney sweeps and finally prevent boys being sent up chimneys.[14]

Climbing boys

- A. a hearth served by vertical flue, a horizontal flue, and then a vertical rise having two right-angled bends that were difficult for brushes.

- B. a long straight flue (14in by 9in) being climbed by a boy using back, elbows, and knees.

- C. a short flue from a second floor hearth. The climbing boy has reached the chimney pot, which has a diameter too small for him to exit that way.

- E. shows a disaster. The climbing boy is stuck in the flue, his knees jammed against his chin.

- G. How a flue could be straightened to make it sweepable by mechanical means

- H. A dead climbing boy, suffocated in a fall of soot that accumulated at the cant of the flue.

The climbing boys, and sometimes girls,[15][16] were technically called chimney sweeps' apprentices, and were apprenticed to a master sweep, who, being an adult, was too large to fit into a chimney or flue. He would be paid by the parish to teach orphans or paupers the craft. They were totally reliant on him: they or their guardians had signed papers of indenture, in front of a magistrate, which bound them to him until they were adults. It was the duty of the Poor Law guardians to apprentice as many children of the workhouse in their care as possible, so as to reduce costs to the parish. The master sweep had duties: to teach the craft and its mysteries, to provide the apprentice with a second suit of clothes, to have him cleaned once a week, allow him to attend church, and not send him up chimneys that were on fire. An apprentice agreed to obey his master.[17] Once his seven-year-long apprenticeship was completed he would become a journeyman sweep, and would continue to work for a master sweep of his choice. Other apprentices were sold on to the sweep, or sold by their parents. Prices ranged from 7 shillings[18] to 4 guineas.

It was generally agreed that six was a good age to train a boy.[19] Though Lord Shaftesbury once encountered one of the age of four, they were considered to be too weak.[19] A master sweep would have many apprentices, who would start the morning by roaming the streets calling out "Soot -Oh, Sweep" or another cry to let the house-owners know they were around; this would remind the owners of the dangers of un-swept chimneys. When engaged, the master sweep would fix a cloth over the fireplace, and the climbing boy would take off his boots and any excess clothes, then get behind it. The flue would be as tall as the house and twist several times, and its dimensions would be 14in by 9in. He would pull his cap down over his face and hold a large flat brush over his head, and wedge his body diagonally in the flue.[20] Using his back, elbows, and knees, he would shimmy up the flue in the manner of a caterpillar[19] and use the brush to dislodge loose soot, which would fall over him and down to the bottom, and a scraper to chip away the solid bits, as a smooth chimney was a safe chimney. Having reached the top he would slide back down at speed back to the floor and the soot pile. It was now his job to bag up the soot and carry it back to the master sweep's cart or yard.

Soot was valuable and could be sold for 9d a bushel in 1840.[21] An apprentice would do four or five chimneys a day. When they first started they scraped their knees and elbows, so the master would harden up their skin by standing them close to a hot fire and rubbing in strong brine using a brush. This was done each evening until the skin hardened.[19] The boys got no wages but lived with the master, who fed them. They slept together on the floor or in the cellar under the sacks and the cloth used during the day to catch the soot. This was known as "sleeping black".[20] The boy would be washed by the mistress in a tub in the yard; this might happen as often as once a week, but rarely. One sweep used to wash down his boys in the Serpentine.[22] Another Nottingham sweep insisted they washed three times a year, for Christmas, Whitsun, and the Goose Fair. Sometimes, a boy would need to be persuaded to climb faster or higher up the chimney, and the master sweep would light either a small fire of straw or a brimstone candle, to encourage him to try harder. One method to stop him from "going off" (asphyxiating) was to send another boy up behind him to prick pins into his buttocks or the soles of his feet.[23]

Chimneys varied in size. The common flue was designed to be one and a half bricks long by one brick wide, though they often narrowed to one brick square, that is 9 inches (230 mm) by 9 inches (230 mm) or less.[24] Often the chimney would still be hot from the fire, and occasionally it would actually be on fire.[18][25] Climbing boys risked getting stuck with their knees jammed against their chins. The harder they struggled the tighter they became wedged. They could remain in this position for many hours until they were pushed out from below or pulled out with a rope. If their struggling caused a fall of soot they would suffocate. Dead or alive, the boy had to be removed and this would be done by removing bricks from the side of the chimney.[26] If the chimney was particularly narrow the boys would be told to "buff it", that is to do it naked;[27] otherwise they just wore trousers and a shirt made from thick rough cotton cloth.

Health and safety concerns

The conditions to which these children were subjected caused concern and societies were set up to promote mechanical means for sweeping chimneys and it is through their pamphlets that we have a better idea of what the job could entail. Here a sweep describes the fate of one boy:

After passing through the chimney and descending to the second angle of the fireplace the Boy finds it completely filled with soot, which he has dislodged from the sides of the upright part. He endeavours to get through, and succeeds in doing so, after much struggling as far as his shoulders; but finding that the soot is compressed hard all around him, by his exertions, that he can recede no farther; he then endeavours to move forward, but his attempts in this respect are quite abortive; for the covering of the horizontal part of the Flue being stone, the sharp angle of which bears hard on his shoulders, and the back part of his head prevents him from moving in the least either one way or the other. His face, already covered with a climbing cap, and being pressed hard in the soot beneath him, stops his breath. In this dreadful condition he strives violently to extricate himself, but his strength fails him; he cries and groans, and in a few minutes he is suffocated. An alarm is then given, a brick-layer is sent for, an aperture is perforated in the Flue, and the boy is extracted, but found lifeless. In a short time an inquest is held, and a Coroner's Jury returns a verdict of "Accidental Death".[28]

These however were not the only occupational hazards that chimney sweeps suffered. In the 1817 report to Parliament, witnesses reported that climbing boys suffered from general neglect, and exhibited stunted growth and deformity of the spine, legs, and arms, which were thought to be caused by being required to remain in abnormal positions for long periods of time before their bones had hardened. The knees and ankle joints were the most affected. Sores and inflammation of the eyelids that could lead to loss of sight, were slow in healing because the boy kept rubbing them. Bruises and burns were obvious hazards of having to work in an overheated environment. Cancer of the scrotum was found only in chimney sweeps so was referred to as Chimney Sweep Cancer in the teaching hospitals. Asthma and inflammation of the chest were attributed to the fact that the boys were out in all weathers.[29]

Chimney sweeps' carcinoma, which the sweeps called soot wart, did not occur until the sweep was in his late teens or twenties. It has now been identified as a manifestation of scrotal squamous cell carcinoma. It was reported in 1775 by Sir Percival Pott in climbing boys or chimney sweepers. It is the first industrially related cancer to be found. Potts described it:

It is a disease which always makes it first attack on the inferior part of the scrotum where it produces a superficial, painful ragged ill-looking sore with hard rising edges ... in no great length of time it pervades the skin, dartos and the membranes of the scrotum, and seizes the testicle, which it inlarges [sic], hardens and renders truly and thoroughly distempered. Whence it makes its way up the spermatic process into the abdomen.

He also comments on the life of the boys:

The fate of these people seems peculiarly hard ... they are treated with great brutality ... they are thrust up narrow and sometimes hot chimnies, [sic] where they are bruised burned and almost suffocated; and when they get to puberty they become ... liable to a most noisome, painful and fatal disease.

The carcinogen was thought to be coal tar, possibly containing some arsenic.[28][30]

There were many deaths caused by accidents, frequently caused by the boy becoming jammed in the flue of a heated chimney, where he could suffocate or be burned to death. Sometimes a second boy would be sent to help and, on occasions would suffer the same fate.[31]

Regulation

In 1788, the Chimney Sweepers Act 1788 (long title: An Act for the Better Regulation of Chimney Sweepers and their Apprentices) was passed, to limit a sweeper to six apprentices, at least 8 years old, but lacked enforcement.[32] It introduced the Apprenticeship Cap badge. The Act had been partially inspired by the interest in climbing boys shown by Jonas Hanway, and his two publications The State of Chimney Sweepers' Young Apprentices (1773) and later Sentimental History of Chimney Sweeps in London and Westminster (1785). He asserted that while Parliament was exercised with the abolition of slavery in the new world it was ignoring the slavery imposed on climbing boys. He looked to Edinburgh, Scotland, where sweeps were regulated by the police, climbing was not allowed and chimneys were swept by the Master Sweep himself pulling bundles of rags up and down the chimney. He did not see how climbing chimneys could be considered a valid apprenticeship, as the only skill obtained was that of climbing chimneys, which did not lead to future employment.[33] Hanway advocated that Christianity should be brought into the boys' lives and lobbied for Sunday Schools for the boys. The Lords removed the proposed clause that Master Sweeps should be licensed, and before civil registration, there was no way that anyone could check if a child was actually eight.

In the same year, David Porter, a humane master sweep, sent a petition to Parliament, and in 1792 published Considerations of the Present State of Chimney Sweepers with some Observations on the Act of Parliament intended for their Relief and Regulation. Though concerned for the boys' welfare he believed that boys were more efficient than any of the new mechanical cleaning machines. In 1796 a society was formed for Bettering the Conditions of the Poor, and they encouraged the reading of Hanway's and Porter's tracts. They had influential members and royal patronage from George III.[34] A Friendly Society for the Protection and Education of Chimney-Sweepers' Boys had been established in 1800.[35]

In 1803, it was thought by some that a mechanical brush could replace a climbing boy (the Human brush), and members of the 1796 society formed The London Society for Superseding the Necessity for Employing Climbing Boys;[34] they ascertained that children had now cleaned flues as small as 7in by 7in, and promoted a competition for a mechanical brush. The prize was claimed by George Smart for what, in effect, was a brush head on a long segmented cane, made rigid by an adjustable cord that passed through the canes.[36]

The Chimney Sweepers Act 1834 contained many of the needed regulations. It stated that an apprentice must express himself in front of a magistrate that he was "willing and desirous". Masters must not take on boys under the age of fourteen. The master could only have six apprentices and an apprentice could not be lent to another master. Boys under fourteen who were already apprenticed must wear brass cap badges on a leather cap. Apprentices were not allowed to climb flues to extinguish fires. Street cries were regulated.[37] The act was resisted by the master sweeps, and the general public believed that property would be at risk if the flues were not cleaned by a climbing boy.

Also that year building regulations relating to the construction of chimneys were changed.

The Chimney Sweepers and Chimneys Regulation Act 1840 made it illegal for anyone under the age of 21 to sweep chimneys. It was widely ignored. Attempts were made in 1852 and 1853 to reopen the issue, another enquiry was convened and more evidence was taken. There was no bill. The Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act 1864, c. 37, tightened controls significantly, by authorizing fines and imprisonment for master sweeps who were ignoring the law, giving the police the power of arrest on suspicion and authorizing Board of Trade inspections of new and remodelled chimneys. Lord Shaftesbury was a main proponent of the Act.

In February 1875 a twelve-year-old boy, George Brewster, was sent up the Fulbourn Hospital chimneys by his master, William Wyer. He stuck and smothered. The entire wall had to be pulled down to get him out and although he was still alive, he died shortly afterward. There was a coroner's inquest which returned a verdict of manslaughter. Wyer was sentenced to six months' imprisonment with hard labour. Lord Shaftesbury seized on the incident to press his campaign again. He wrote a series of letters to The Times and in September 1875 pushed another bill through Parliament which finally stopped the practice of sending boys up chimneys.[38][39]

The Chimney Sweepers Act 1875 required chimney sweepers "to be authorized by the police to carry on their businesses in the district", thus providing the legal means to enforce all previous legislation.[32]

United States

The history of sweeping in the United States varies little from that in the United Kingdom. Differences arise from the nature of housing and the political pressures. Early settler houses were built close together out of wood, so when one burnt it spread quickly to neighbouring properties. This caused the authorities to regulate the design of flues. From an early date, fire wardens and inspectors were appointed.

Sweeping of the wide flues of these low buildings was often done by the householder himself, using a ladder to pass a wide brush down the chimney. In a narrow flue, a bag of bricks and brushwood would be dropped down the chimney. But in longer flues climbing boys were used, complete with the tradition of coercion and persuasion using burning straw and pins in the feet and the buttocks.[7] Sweeping was not a popular trade. During the eighteenth century the employment of African-American chimney sweeps spread from the south to the north. African-American sweeps faced discrimination and were accused of being inefficient and starting fires. It was claimed that there were fewer fires in London where chimneys were swept by white boys than in New York City. As in the UK, Smart's sweeping machine was available in the US shortly after 1803, but few were used. Unlike the UK, there were no societies formed to advocate for the climbing boys. In fact, the contemporary novel Tit for Tat went so far as to deny the black slave chimney sweeps' hardships by claiming that they had it easier than the London chimney sweeps.[40]

Sweeps' festivals

The London boys had one day's holiday a year, the first of May (Mayday). They celebrated by parading through the streets, dancing and twisting with Jack in the Green, merging several folk traditions.[41] There is also a Sweeps' Festival in Santa Maria Maggiore in Italy,[42] and in Rochester in Kent[43] where the tradition was revived in 1980.

Good luck omen

- In Great Britain it is considered lucky for a bride to see a chimney sweep on her wedding day. Many modern British sweeps hire themselves out to attend weddings in pursuance of this tradition.[44][45]

- In Germany, Poland, Hungary, Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Romania, and Estonia, chimney sweeps still wear the traditional all-black uniform with a black or white hat. It is considered good luck to rub or grasp one of your buttons if you pass one in the street.[citation needed]

- As a lucky symbol, depictions of chimney sweeps are a popular New Year's Day gift in Germany; either as small ornaments attached to flower bouquets or candy, e.g. marzipan chimney sweeps.[46] Their traditional uniform is an all black suit with golden jacket buttons and a black top hat.

Today

Today, chimney sweeps are still operating, as venting systems for coal, heating oil, natural gas, and wood- and pellet-burning appliances need to be maintained. There is a greater understanding of the dangers of flue deposits and carbon monoxide and gases from combustion. The standard chimney brush is still used, along with more modern tools (such as vacuum cleaners, cameras, and special chimney cleaning tools).[example needed] Most sweeps are done from the bottom of the chimney, rather than the top, to prevent the dispersion of dust and debris and because it is safer for the chimney sweep to do the sweeping from this position. Inspection may be done from the bottom or top, or both if accessible. Chimney sweeps often encounter a range of unexpected objects[47] in chimneys ranging from dead birds to tools, notes, love letters, and other pieces of ephemera.

Most modern chimney sweeps are professionals, and are usually trained to diagnose and repair hazards along with maintenance such as removal of flammable creosote, firebox and damper repair, and smoke chamber repair. Some sweeps also offer more complicated repairs such as flue repair and relining, crown repair, and tuckpointing or rebuilding of masonry chimneys and cement crowns.

In the United States, the two trade organizations that help to regulate the industry are the Chimney Safety Institute of America and The National Chimney Sweep Guild. Certification for chimney sweeps are issued by two organizations: Certified Chimney Professionals and The Chimney Safety Institute of America, which was first to establish certification and requires sweeps to re-test every three years or demonstrate the commitment to education by earning CEUs through CSIA or the National Fireplace Institute to bypass the test. Certification for chimney sweeps who reline chimneys are issued by Certified Chimney Professionals and the Chimney Safety Institute of America. CEU credits may be obtained from these organizations and regional associations as well as private trainers.

In the United Kingdom Chimney Sweeping is unregulated however many sweeps have organised themselves into trade associations including the Association of Professional Independent Chimney Sweeps,[48] the Guild of Master Chimney Sweeps,[49] and The National Association of Chimney Sweeps.[50] As well as offering support to members they provide training and representation to DEFRA and other interested parties.

See also

- Chimney sweeps' carcinoma

- Spazzacamini, a.k.a. Kaminfegerkinder

References

Citations and notes

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 40

- ^ Green, Kathleen (2010). "You're a What? Chimney Sweep". Occupational Outlook Quarterly. 54 (2): 30–31. ISSN 0199-4786.

- ^ Hidden Killers: The Horrors of Tudor Dentistry and other household ietms

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 7

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 64

- ^ Strange 1982, p. xiii

- ^ a b Strange 1982, p. 90

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 80

- ^ Burke 1995, p. 159

- ^ Strange 1982, pp. 5–6

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 30

- ^ Waldron 1983, p. 390

- ^ Strange 1982, pp. 46–47

- ^ Strange 1982, p. xiv

- ^ Mayhew 1861, p. 347

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 19

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 12

- ^ a b Strange 1982, p. 21

- ^ a b c d Strange 1982, p. 14

- ^ a b Strange 1982, p. 18

- ^ Mayhew 1861, p. 353

- ^ Strange 1982, pp. 71, 72

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 13

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 16

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 27

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 26

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 71

- ^ a b Waldron 1983, p. 391

- ^ Mayhew 1861, p. 350

- ^ Schwartz, Robert A. (2008). Skin Cancer: Recognition and Management (3 ed.). Wiley. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-470-69563-0. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Mayhew 1861, p. 351

- ^ a b "Key dates in Working Conditions, Factory Acts (Great Britain 1300 – 1899)". Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 37

- ^ a b Strange 1982, p. 43

- ^ (The Times 16 April 1800, Page 1, Column b.)

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 44

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 65

- ^ "2 The Asylum Years". human-nature.com. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 31

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 93

- ^ Mayhew 1861, p. 370

- ^ "Museo dello Spazzacamino – Home page". museospazzacamino.it. 10 September 2012. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Rochester Sweeps Festival Archived 3 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Chimney sweep weddings". chimneycleaners.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "History | Lucky Chimney Sweep". Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ File:German new year's gift, four leaf clovers with chimney sweep ornament.jpeg

- ^ "Strange Objects in Chimneys". Exeter Chimney Sweep. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ The Association of Professional Independent Chimney Sweeps.

- ^ the Guild of Master Chimney Sweeps.

- ^ The National Association of Chimney Sweeps.

Bibliography

- Mayhew, Henry (1861). London Labour and the London Poor: A Cyclopedia of the Condition and Earnings of those who will work,...etc. Vol. 2 (Cosimo Classics 2008 ed.). Cosimo. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-60520-735-3. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Strange, K.H. (1982). Climbing Boys: A Study of Sweeps' Apprentices 1772–1875 (PDF). London/Busby: Allison & Busby. ISBN 0-85031-431-3. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Waldron, H.A. (1983). "A brief history of scrotal cancer". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 40 (4): 390–401. doi:10.1136/oem.40.4.390. PMC 1009212. PMID 6354246.

- Burke, James (1995). Connections. Little, Brown and Co. p. 159. ISBN 0-316-11672-6.

External links

- BBC Schools Radio Archived 4 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine: Audio dramatisation of climbing boys testament.

Modern trade associations:

United States: