Chavín culture

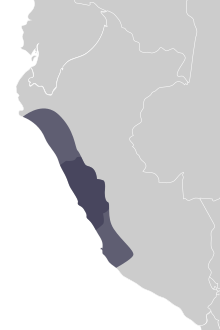

The area of the Chavín civilization, as well as areas with Chavín cultural influences | |

| Period | Early Horizon |

|---|---|

| Dates | 900 – 250 BCE |

| Type site | Chavín de Huántar |

| Preceded by | Kotosh |

| Followed by | Moche, Lima, Nazca |

The Chavín culture was a pre-Columbian civilization, developed in the northern Andean highlands of Peru around 900 BCE, ending around 250 BCE. It extended its influence to other civilizations along the Peruvian coast.[1][2] The Chavín people (whose name for themselves is unknown) were located in the Mosna Valley where the Mosna and Huachecsa rivers merge. This area is 3,150 metres (10,330 ft) above sea level and encompasses the quechua, suni, and puna life zones.[3] In the periodization of pre-Columbian Peru, the Chavín is the main culture of the Early Horizon period in highland Peru, characterized by the intensification of the religious cult, the appearance of ceramics closely related to the ceremonial centers, the improvement of agricultural techniques and the development of metallurgy and textiles.

The best-known archaeological site for the Chavín culture is Chavín de Huántar, located in the Andean highlands of the present-day Ancash Region. Although Chavín de Huántar may or may not have been the center or birthplace of the Chavín culture, it was of great importance and has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Achievements

The chief example of architecture is the Chavín de Huántar temple. The temple's design shows complex innovation to adapt to the highland environments of Peru. To avoid the temple's being flooded and destroyed during the rainy season, the Chavín people created a successful drainage system. Several canals built under the temple acted as drainage. The Chavín people also showed advanced acoustic understanding. During the rainy season water rushes through the canals and creates a roaring sound that emulates a jaguar, a sacred animal.[4] The temple was built of white granite and black limestone, neither of which is found near the Chavín site. This meant that leaders organized many workers to bring the special materials from far away rather than use local rock deposits. They also may have been traded from different civilizations in the area.

The Chavín culture also demonstrated advanced skills and knowledge in metallurgy, soldering, and temperature control. They used early techniques to develop refined gold work. The melting of metal had been discovered at this point and was used as a solder.[5] Furthermore, the people domesticated camelids such as llamas. Camelids were used for pack animals, for fiber, and for meat. They produced ch'arki, or llama jerky.[6] This product was commonly traded by camelid herders and was the main economic resource for the Chavín people. The Chavín people also successfully cultivated several crops, including potatoes, quinoa, and maize. They developed an irrigation system to assist the growth of these crops.[7]

Language

There is an absence of written language,[8] so the language spoken by the Chavín people is not known, but it is likely now extinct.[9] Some anthropologists have proposed that it was a form of Proto-Quechuan, reasoning that the Quechuan languages' highly regular morphology and syntax compared to surrounding languages would have been useful for allowing intelligible communication between communities separated by mountain ranges, as some Chavín groups were.[10] On the other hand, Alfredo Torero dates the Proto-Quechuan languages to around the beginning of the first millennium CE when the first Chavín people had a religion.

Architecture

Chavín de Huántar was the place of origin of the second large-scale political entity in the central Andes, and this is mainly due to the extensive architecture at the site[11] as well as the architecture is considered an engineering accomplishment.[8] The site uses both internal and external architecture. Internal architecture refers to galleries, passageways, rooms, staircases, ventilation shafts, and drainage canals. External architecture refers to plazas, platform mounds, and terraces.[12] Construction of the "Old Temple" took place from around 900 to 500 BCE, and construction of the "New Temple", the structure that was constructed and added on to the "Old Temple", took place from around 500 to 200 BCE. The lack of residential structures, occupational deposits, generalized weaponry, and evidence of storage further make the site's architecture more interesting, as it focuses mainly on the temples and what lies inside of them.[13]

The monumental center at Chavín de Huántar was built in at least 15 known phases, all of which incorporate the 39 known episodes of gallery construction. The earliest known construction stage, the Separate Mound Stage, consisted of separate buildings[12] and do not conform, necessarily, to the U-shaped pattern seen in the Initial Horizon Period and the Early Horizon Period. During the Expansion Stage, construction integrated stepped platforms and created contiguous U-shaped form by connecting the buildings, which now surround open spaces. At this stage, galleries are elaborate in form and features. During the Black and White Stage, all known plazas (the Plaza Mayor, Plaza Menor, and the Circular Plaza) were constructed. As construction came to an end, galleries took on a more standardized look.[12] By the end of the growth process, buildings become plazas with a U-shaped arrangement and an east-west axis bisecting the enclosed space. The axis also intersects the Lanzón.[11]

Modifications were done during all stages of construction to maintain access to the internal architecture of the site.[12] There was a high level of interest in maintaining access to internal architecture and sacred elements of the site. The internal architecture was constructed as part of a single design and was intricately incorporated with the external architecture.[12] Including lateral and asymmetrical growth allowed for these sacred elements to remain visible, including the Lanzón.

The Lanzón Gallery was created from an earlier freestanding structure that was then transformed into a stone-roofed internal space by constructing around it. The Lanzón was possibly present before the roofing, as it is likely that the Lanzón predates the construction of mounds and plazas.[11] In general, galleries follow construction patterns, which indicates a massive effort in design and planning. Maintaining these galleries over time was important to architects.[12] The galleries are known to be windowless, dead ends, sharp turns and changes in floor height, all of which were designed to disorient people walking in them.[14]

A combination of symmetry and asymmetry was used in the design and planning of the site construction, and in fact, guided the design. There were centered placements of staircases, entrances, and patios, all of which were consistently prominent. In the last stages of construction, due to constraints, centeredness was no longer possible, so architects shifted to constructing symmetrical pairs. Externally, buildings were asymmetrical to each other.[12]

The primary construction materials used were quartzite and sandstone, white granite, and black limestone. Alternate coursing of quartzite was used in the major platforms, while white sandstone and white granite were used interchangeably in the architecture, and were almost always cut and polished. Granite and black-veined limestone were the raw materials used in almost all of the engraved lithic art at the site. Granite was also used extensively in the construction of the Circular Plaza.[11]

Stone-faced platform mounds at the site were made using an orderly fill of rectangular quartzite blocks in leveled layers. Platforms were built directly on top of fallen wall stones from earlier constructions, as there was little to no attempt to remove debris.[11]

Art

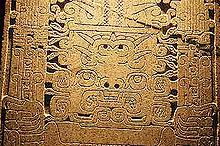

The Chavín culture represents the first widespread, recognizable artistic style in the Andes. Chavín art can be divided into two phases: The first phase corresponding to the construction of the "Old Temple" at Chavín de Huántar (c. 900–500 BCE); and the second phase corresponding to the construction of Chavín de Huántar's "New Temple" (c. 500–200 BCE).

Chavín art is known for its complex iconography and its "mythical realism".[15] There is constant evidence within all types of art (ceramics, pottery, sculptures, etc.) of human-animal interactions, which was reflective of societal interconnections and how the Chavín people viewed themselves connected with "the other world".[8]

Some other iconography found in Chavín art continues to give a glimpse as to what the culture was like, such as the general evidence of the use of psycho-active plants in ritual. The San Pedro Cactus is often seen on various art forms, sometimes being held by humans, which is used as evidence to support the use of the plant.[16] The stone sculpture stela of the cactus bearer shows an anthropomorphized being with serpent hair, a mouth with fangs, a belt with a two-headed serpent and claws, who in their right hand holds what appears to be a San Pedro cactus.[17]

A general study of the coastal Chavín pottery with respect to shape reveals two kinds of vessels: a polyhedral carved type and a globular painted type.[18] Stylistically, Chavín art forms make extensive use of the technique of contour rivalry. The art is intentionally difficult to interpret and understand, since it was intended only to be read by high priests of the Chavín cult, who could understand the intricately complex and sacred designs. The Raimondi Stele is one of the major examples of this technique. Ceramics, however, do not appear to represent the same stylistic features that are found on sculptures.[15]

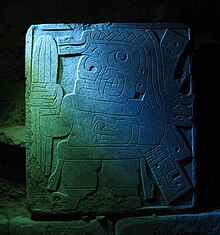

Chavín art decorates the walls of the temple and includes carvings, sculptures and pottery. Artists depicted exotic creatures found in other regions, such as jaguars and eagles, rather than local plants and animals. The feline figure is one of the most important motifs seen in Chavín art. It has an important religious meaning and is repeated on many carvings and sculptures. Eagles are also commonly seen throughout Chavín art. There are three important artifacts which are the major examples of Chavín art. These artifacts are the Tello Obelisk, tenon heads, and the Lanzón.

Tello Obelisk is a vertical, rectangular shaft with a step-like notch at the top. The obelisk is carved in relief on all four sides and consists of two representations of a single-type creature. The head, body and tail occupy one or the other broad sides, while the legs, genitalia and other subsidiary elements occupy the narrow sides. These creatures have been interpreted as a "cat-dragon" type of creature (by Tello) and as a cayman (by Rowe and Lathrop).[19] The large artifact may portray a creation myth.

Tenon heads are found throughout Chavín de Huántar and are one of the most well-known images associated with the Chavín civilization. Tenon heads are massive stone carvings of fanged jaguar heads which project from the tops of the interior walls.

Possibly the most impressive artifact from Chavín de Huántar is the Lanzón. The Lanzón is a 4.53-meter-long carved granite shaft displayed in the temple. The shaft extends through an entire floor of the structure and the ceiling. It is carved with an image of a fanged deity, a recurring image throughout the Chavín civilization.[20] The Lanzón is found in a gallery inside of the Old Temple. The sculpture is enhanced by the four openings of the chamber it lies in, making it so that it allows only partial and segmented views. In rollout drawings, the figures depicted are coherent to interpreters, but it's important to note that this is not how the Lanzón is meant to be seen.[21]

Sphere of influence

The Chavín culture had a wide sphere of influence throughout surrounding civilizations, especially because of their location at a trade crossing point between the deserts and Amazon jungle. For example, Pacopampa, located north (about a 3-week trek) of Chavín de Huántar, has renovations on the main temple that are characteristic of Chavín culture. Caballo Muerto, a coastal site in the Moche Valley region, has an adobe structure created during renovation of the main temple, the adobe related to Chavín influence. Garagay, a site in the modern-day Lima region, has variations of the characteristic Chavín iconography, including a head with mucus coming from the nostrils. At the site of Cerro Blanco, in the Nepena valley, excavations revealed Chavín ceramics.

Warfare does not seem to have been a significant element in Chavín culture. The archaeological evidence shows a lack of basic defensive structures in Chavín centres, and warriors are not depicted in art, in notable contrast to the earlier art at Cerro Sechín. Effective social control may have been exercised by religious pressure, and the ability to exclude dissidents from managed water resources. The climate and terrain of the neighbouring areas outside the managed land were a daunting option for farmers wishing to flee the culture.[22] Evidence of warfare has been found only in contemporaneous sites that were not influenced by Chavín culture, almost as if those other civilizations were defending themselves via warfare from Chavín cultural influence.[1][dubious – discuss]

Chavín culture as a style, and probably as a period, was widespread, stretching from Piura on the far north coast to Paracas on the south coast; and from Chavín in the north highlands to Pucará in the south highlands.[23]

Chavín horizon development

Some scholars argued that the development of Chavín social complexities coincided with the cultivation of maize and development of agricultural surpluses. Through an analysis of carbon isotope in the human bones found at Chavín sites, researchers have proved that the diet consisted mainly of C3 foods such as potatoes and quinoa, while maize, a C4 food, was not a part of the main diet. Potato and quinoa were crops better adapted to the Chavín environment. They are more resistant to the frost and irregular rain fall associated with high-altitude environments. Maize would not have been able to thrive in such conditions.[2]

Pre-Chavín levels

The Kotosh Religious Tradition preceded the Chavín culture at various sites. Some Kotosh elements show links with the Chavín culture, such as for example the ceramic styles.[24][25]

Prior to Kotosh was the Wairajirca Period. This is when the first pottery appeared. The Mito tradition was even earlier. This was a preceramic tradition. Nevertheless, public buildings were constructed.

Chavín levels

The Chavín culture archaeological horizon, itself, has three ceramic stages. They were originally identified through stratified ceramics and encompass three stages of development for the Chavín culture.

- Urabarriu, the first stage, extends from 900 to 500 BCE. During this time at Chavín de Huántar, two small residential areas, not located directly surrounding the ceremonial center, housed a few hundred people in total. This phase showed the greatest animal diversity. The people hunted mainly deer and began to hunt and use camelids. They ate clams and shellfish from the Pacific Ocean, as well as guinea pigs and birds. Chavín people grew some maize and potatoes during this phase.[6] The ceramics in the Urabarriu stage are highly influenced by other cultures.[1] The archeological evidence suggests dispersed centers of production for ceramics, probably in response to a low demand from the dispersed population.[26]

- The Chakinani, 500 to 400 BCE, is a short time of transition in Chavín culture. During this time the residents migrated to surround the ceremonial center. The Chavín began to domesticate the llama and reduced deer hunting. Evidence of increased exchange with outside civilizations is also seen at this time.[1]

- The Jarabarriu, the final stage of the Chavín Horizon, lasted from about 400 to 250 BCE. Chavín culture had a dramatic increase in population. The settlement pattern changed to a proto-urban pattern, consisting of a center of lowland valley peoples and smaller satellite communities in the surrounding higher altitude areas. The culture showed specialization and social differentiation. The people who lived in the east at Chavín de Huántar are thought to have had lower prestige than the communities around the ceremonial center.[1] A diverse and intense production of ceramics is suggested during the Jarabarriu phase, when the valley was heavily populated and the ceramic style more defined. Satellite communities also developed centers of production during this phase.[26]

Presence of elite

At Chavín, power was legitimized through the belief in the small elite having a divine connection; shamans derived power and authority from their claim to a divine connection.[dubious – discuss] The community believed in and had a desire to connect with the divine. With asymmetrical power, there is often evidence of the manipulation of traditions.

Strategic manipulation is a vehicle of change which shamans could use to produce authority. During the Chavín horizon, large changes were taking place.[27][28]

"The greater degree of elaboration of persuasion evident in the rites, materials, and settings of the belief system, the more likely that not only were the leaders aware of being self-serving in their actions but also they were actually conscious of the trajectory change."[27] The archeological evidence shows several examples of reinterpretation, use of psychotropic drugs, and landscape altering. It also shows the complex planning and construction of stone-walled galleries.[27]

The concept of invented tradition refers to a situation in which outside elements are newly brought together to depict a seemingly old tradition. This can be seen generally in the architecture at Chavín de Huántar, which bring together many aspects of outside cultures to create a unique new, yet traditional appearance.[27][28][29]

The use of psychotropic drugs introduces a medium for manipulation. Only indirect evidence supports the use of psychotropic drugs, as noted above. Scholars have not been able to determine if the San Pedro cactus was ingested, who consumed the cactus: only the shaman elite, or more widespread among the masses. If the masses were taking the cactus, they would be more susceptible to the influences of the shamans. If the shamans were the only ones to consume it, the practice may have been sacred and a status symbol. The shamans would be perceived to have special powers to connect with nature and the divine.[27][28]

The extensive degree of landscape altering at Chavín de Huántar for temple reconstructions shows that someone or a group of people had the power to plan the reconstructions and influence others to carry out those plans. The large constructions that occurred at this site support the hypothesis of asymmetrical power.[27][28]

Finally, the planning and construction of the stone-walled galleries, in particular, suggest a hierarchical system. In addition to the requirement to command and direct the manpower required, the galleries show unique planning. They allowed only one entrance; this is atypical of the time when rooms commonly had multiple entrances and exits. The iconography on the walls of the stone galleries is highly complex. The complexity suggests that only a select few people were able to understand the iconography; such people would serve as translators for the few others who were privileged to view the stone galleries. The limited access, both physically and symbolically, of the stone-walled galleries, supports the existence of a shaman elite at Chavín de Huántar. The evolution of authority at Chavín appears to have resulted from a planned strategy by the shamans and those who planned and constructed the ceremonial center.[27]

Religion and ritual

Religion and the practices which followed had a deeper connection to the sociopolitical and economic aspects within the Chavín society.[30] Ritual activity for the Chavín is not fully understood, but a great understanding of the overall ritual influence and impact that ritual had on the Chavín is more evident through their architectural structures, offering deposits, and artistic remains, mainly through pictographic displays.[30] Over time, the effects of ritual moved to be more intimate and exclusive, as evident with the use and development of ritual space and architecture.[30] Religious figures played a large role in how the site was designed and how rituals were oriented.

Sacred spaces: ritual architecture

The overall architecture at Chavín had religious influence and significance. The sacred spaces and structures within this society were evident to have ritualistic and potentially religious purposes.[30] Understanding how the site of Chavin de Huántar is designed allows modern individuals to recognize how the site reflects intentionality of the builders to relay a specific experience.[14] The site was considered to be sensory, meaning that the architectural structure and design elicited a certain feeling through the senses, through sight and touch.[14] It is perception, which is essentially a series of physiological responses.[14] Sacred spaces, such as plazas, were designed to mainly disrupt visual impact, meaning that the sacred architecture was designed to be experienced more so than actually viewed.[30] People who designed and built the architecture at Chavín are understood to be priests or religious leaders within the community.[13] Configuration of the site also emphasizes that there was a presence of high-ranked officials.[13] The architecture within Chavín was dictated by these individuals to keep the ritual elements of their culture prominent.[30] This was done so through the details and formatting of each building, which in essence created the effect that those participating in the ritual were experiencing their religious phenomena. Construction of the sacred ritual spaces was done with a diverse labor pattern and no central authority was controlling the area during its actual construction.[30] The ritual architecture of the Chavín is similar to other Andean coastal architecture.[30]

The earliest architectural forms on the site were plastered, rectangular chambers. One of these later housed the Lanzon. The architecture of the Chavín site allowed for a rich and diverse ritual practice within the ritualized spaces, leading scholars to speculate whether or not the Chavín served as a multi-ethnic ceremonial center; the architecture, materials, and offerings might have been inspired by other cultures, but there is a question as to whether or not it was symbolic of a greater diverse ritual practice.[30] The ritual spaces themselves had a hierarchy, and legitimized and reflected cosmological and social order and structure.[30]

The Chavín buildings and spaces used for ritual were constructed to elicit an experience, and encompassed many of the overall architectural facets described previously. Two of the most well-noted ritual spaces include the Old Temple and New Temple, with a shift to the New Temple as time progressed.[30] Both temples featured pathways and deity worship spaces on the north and south wings.[30] In addition to this, the temples, most notably the Old Temple, had deities carved into stone.[31] The temples were conformed into a U-shaped area, encompassing a circular plaza.[30] The temples featured ceremonial chambers and sacred hearths.[30] Another important structure designed and utilized for ritual included plazas, of which there were many. The Circular Plaza in particular and the Square Plaza were two of the sites primarily focused around ceremonial activity.[30]

Within the Chavín site was a structure which revealed rooms and galleries, speculated by archaeologists to be used as “ritual chambers” for a variety of ceremonies, including what could have been a ceremony surrounding fire.[30] Major use of underground space in the form of stone-lined galleries that are often like labyrinths and run through the monuments’ major platforms and mounds has been speculated to be a center for religious activity where ceremonies occurred in several different contexts involving both audiences and participants.[13]

The open spaces of plazas versus the small restricted spaces of Chavín galleries in the temple shows that there is a progression of how the ritual spaces and architecture was used, moving more from public to private practice.[30] The gallery spaces are central to understanding the implications of the Chavín ritual practices.[30]

In fact, these underground galleries were more than just a place of ritual. As was recently discovered in 2018 by a team of archaeologists led by John Rick,[32] through the use of all-terrain robots, these galleries were the final resting place for, presumably, the temple's builders. The men's bodies weren't buried in a very honorable way: they were face-down, covered by rocks.[32] John Rick raised the possibility, yet to be confirmed, that these people could very well have been sacrificed. This discovery shed some light as to where the people of Chavín buried their dead, although there might be other burial sites, as the director for the excavation said that he doesn't believe it was customary to bury them in those galleries, just that it sometimes happened.[32] If it becomes known, through the study of the remains, that they were indeed sacrificed, it could also serve to prove the theory that the galleries were a place of ritual, but for now, we can only know for sure that it was the final resting place for the men who built the temple.

The sizes of the spaces in the sacred spaces provided different amounts of room for people to congregate.[30] External spaces such as the plazas had the ability to hold more individuals for ritual practices. The Square Plaza could have held 5,200 individuals. The Circular Plaza could have held around 600 individuals. Internal spaces within the temples, for example the galleries or hallways, could have only held a small number.[30] Within the Lanzon gallery in the Old Temple, only around 15 people could have attended a ceremony, and within the canal entries only 2 to 4 people could have witnessed the ceremony.

Practices and ceremonies

Ritualistic activity for Chavín is not necessarily original; it has deep roots connected to activities from other (Andean civilisations|Andean) societies and cultures. The rituals in the space might have been indicative of the other diverse practices that took place at that time.

The want for more followers extended more deeply than numbers, but rather the Chavín wanted to establish a central authority as well as socially integrate diverse societies. Ritual practice at this time evolved and showed evidence of both public and private religion, and showed an increased distance between participants and observers in public ceremonies. Participants are termed in the archaeology community as visitors to the site. The transition was not immediate, as ancient practices were highly appealed to frequently as rituals progressed.

There is debate as to whether or not the Chavín practices were more hierarchical or hierarchical. It is believed by archaeologists that for the Chavín to have the most successful and impact rituals, they must be more condensed and more private in their nature. But other evidence shows that central areas reflected the lack of hierarchy in ritual practice, and that the society utilised the open spaces to better demonstrate a more inclusive religious experience. This demonstrates that ritual practice might have been hierarchical or hierarchical, and reflects back to the ideas of their exclusivity with other religious institutions, rituals, and traditions. Regardless, it is understood and well accepted that the Chavin were inclusive in their ritual practices.

Important aspects of Chavín ritual activity and practice have been discovered to be processions, offerings of different materials (exotic and valuable), and the use of water. One of these offerings can be connected to the smashed pieces of obsidian found along with fragments of mirror. Other ceremonial acts for the Chavín included the smashing of pots and ceremonies surrounding the use of fire, held within certain areas of the Chavín site as a part of their ritual. Artefacts in the temples relay the ritual practice of offerings. Ceramics, for example, were believed to be offerings brought by the pilgrims. Another artefact was a conch shell, used as a trumpet. Art suggests that processions were essential to disclosing that processions were an important part of Chavín ritual. Other ritual practices were produced by the shamans, such as divination, celestial observations, calendar calculations, health, and healing.

One other ritualistic element included the use of psychotropic drugs through mescaline containing cacti. The cacti provided a psychedelic drug that caused a lot of sensory overloads. It has been displayed in art, specifically ashlar blocks with costumed figures in procession carrying the cacti.[14] Ritual evidence in the architectural remains shows that there was paraphernalia for grinding and ingesting snuff.[14] Artistic evidence shows that certain drawings were done by shamans whilst under the influence of the psychedelic drugs.[14]

Music also played a role in Chavín ritual. Strombus shell trumpets were found at Chavín sites.[30] Trumpets were stored underground and it is believed that they were used by ritual practitioners, who would use them and play in procession through the underground galleries.[14]

Religious art

Religious art is reflective of the landscape around the Chavín and everyday experiences they lived through, including that which can be affiliated with religious practices. Art implied that there were certain deities within the Chavín culture, as well as symbols indicative of ritualistic activities. Lithic art, for example, indicates that processions were important to Chavín ritual.[30] Other artistic expressions included images of jaguars and hybrid humans with felines, avians, and crocodilian features.[14] These in particular are done through artistic interpretations and were believed to have been done by shamans under the influence of the psychedelic drugs. In addition to animals, art reflected plant life, including images of the cacti used as a psychedelic drug.

Deities

Deities were an important element in Chavín religious practice. Most important to the Chavín was the Lanzón, the most central deity in Chavín culture, making the Lanzón central to religious practices.[30] It is believed to be a founding ancestor who had oracle powers.[31] The statue of the Lanzón was carved into a large stone and was found within the Old Temple.[30] It was originally in the rectangular chamber,[30] and is considered to be the focal point of the Old Temple. It is carved out of stone and stands at 4.5 meters tall.[31] The Lanzón is also represented in the New Temple. Other deities reflected the landscape around the Chavín, including animals in nature and the cosmos, and included figures such as crested eagles, hawks, serpents, crocodiles (caymans), and jaguars. They were intermingled with human aspects, becoming more of a hybrid. The Chavín were also interested in binaries and manipulating them, such as showing men and women, the sun and moon, and the sky and water in the same image.

Religious figures

Religious figures played a role in the Chavín religious ritual. In general, individuals higher up in the societal hierarchy had control over the management of the ritual activities and brought the Chavín ritual into the society.[30] Shamans are most commonly understood to be the primary religious figure. Leaders managed daily secular functioning, and it corresponded with authority figures leading from a small group, rather than having one individual as the head figure.[31] They lived close to the temple in residential buildings. Leaders demonstrated skills in understanding the supernatural world with the ability to manipulate it, thus making them stand out to be a religious figure.

Gallery

- The sandeel monolithic has a length of 5 meters and represents a Chavín deity. It is located in the Ancient Temple in Chavín de Huántar.

- Gold Chavín. Larco Museum, Lima

- Gold Chavín

- Chavín Gold Necklace

- Condor head, at the National Museum of Chavín de Huántar.

- Chavin tenon head

- The tusks are present in all the arts of Chavín including in the sculpture as this tenon head.

- Tenon head embedded in one of the walls of the temple of Chavín de Huántar.

- Stela Chavín. National Museum Chavín de Huántar.

- There are many Chavínes trails representing mythological creatures like this.

- Stela Chavín with image of an ornithological.

- Chavín stela depicting a brindle face. National Museum Chavín de Huántar.

- The ceremonial centre of Kuntur Wasi, according to the latest archaeological research would be an prechavín expression associated to felínico Chavín cult. Cajamarca Region.

- Remains of Pacopampa, another prechavín expression of Formative stage period but remained an important ceremonial centre like Chavín de Huántar, also located in the Cajamarca Region.

- Model of the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar.

- The llama was the main representative of Chavín livestock.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Burger, Richard L. 2008 "Chavin de Huantar and its Sphere of Influence", In Handbook of South American Archeology, edited by H. Silverman and W. Isbell. New York: Springer, pp. 681–706

- ^ a b Burger, Richard L., and Nikolaas J. Van Der Merwe (1990). "Maize and the Origin of Highland Chavín Civilization: An Isotopic Perspective", American Anthropologist 92(1):85–95.

- ^ Burger (1992), Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization

- ^ Luis Guillermo Lumbreras, Acerca de la función del sistema hidráulico de Chavín, 1976

- ^ Lothrop, S. K. (1951) "Gold Artifacts of Chavin Style", American Antiquity 16(3):226–240

- ^ a b Miller and Burger, 1995

- ^ Burger and Van Der Merwe, 1990

- ^ a b c Conklin, William J. (2008). Chavín: Art, Architecture and Culture.

- ^ Wolfson, Nessa; Manes, Joan. Language of Inequality. p. 186.

- ^ Campbell, Lyle; Grondona, Verónica. The Indigenous Languages of South America: A Comprehensive Guide. p. 588.

- ^ a b c d e Rick, John W. "Context, Construction, and Ritual in the Development of Authority at Chavín de Huantar". Chavín: Art, Architecture, and Culture.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kembel, Silvia Rodriguez. "The Architecture at the Monumental Center of Chavín de Huántar: Sequence, Transformation and Chronology". Chavín: Art, Architecture and Culture.

- ^ a b c d Rick, John (2017). Rituals of the Past: Prehispanic and Colonial Case Studies in Andean Archaeology. University Press of Colorado. pp. 21–46. ISBN 9781607325963.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weismantle, Mary (2013). Making Senses of the Past : Toward a Sensory Archaeology. Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 113–133.

- ^ a b Bischof, Henning. "Context and Content of Early Chavín Art". Chavín: Art, Architecture and Culture.

- ^ Torres, Constantino Manuel. "Chavín's Psychoactive Pharmacopoeia: The Iconographic Evidence". Chavín: Art, Architecture and Culture.

- ^ Morris, Hamilton (2012-06-19). "Desvelando los criptocactos". www.vice.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-11-24.

- ^ Tello, Julio C. (1943) "Discovery of the Chavín Culture in Peru", American Antiquity 9(1, Countries South of the Rio Grande):135–160.

- ^ Urton, Gary. "The Body of Meaning in Chavín Art". Chavín: Art, Architecture and Culture.

- ^ Burger, Richard L. Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1992.

- ^ Cummins, Tom. "The Felicitous Legacy of the Lanzón". Chavín: Art, Architecture and Culture.

- ^ Burger (1992), pp. 78-79, 225, 65, 78

- ^ Bennett, Wendell C. (1943) "The Position of Chavin in Andean Sequences", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 86(2, Symposium on Recent Advances in American Archeology):323–327.

- ^ Izumi and Sono, 1963, p. 155

- ^ Seiichi IZUMI, Pedro J. CUCULIZA, Chiaki KANO, INTRODUCTION, Bulletin No.3: EXCAVATIONS AT SHILLACOTO, HUANUCO, PERU. Archived 2003-01-13 at the Wayback Machine The University Museum, University of Tokyo, 1972

- ^ a b Druc, Isabelle C. 2004 "Ceramic Diversity in Chavín De Huantar, Peru", Latin American Antiquity 15(3):344–363.

- ^ Burger, Richard (1992) "Sacred Center at Chavin de Huantar", In The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Contreras, Daniel A. (2017). Rituals of the Past: Prehispanic and Colonial Case Studies in Andean Archaeology. University of Colorado. pp. 51–77.

- ^ a b c d Peregrine et a., P. N. (2002). "Chavin". Encyclopedia of Prehistory – via 41.

- ^ a b c "Robots help find new underground galleries in Peru's Chavín de Huántar". The Archaeology News Network. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

Sources

- Bennett, Wendell C. (1943) "The Position of Chavin in Andean Sequences", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 86(2, Symposium on Recent Advances in American Archeology), [323–327].

- Burger, Richard L. and Nikolaas J. Van Der Merwe. "Maize and the Origin of Highland Chavin Civilization: An Isotopic Perspective", American Anthropologist 92, 1 (1990), [85–95].

- Burger, Richard L. 1992 Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Burger, Richard L. 1992 "Sacred Center at Chavin de Huantar". In The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. Art Institute of Chicago, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

- Burger, Richard L. 2008 "Chavin de Huantar and its Sphere of Influence", In Handbook of South American Archeology, edited by H. Silverman and W. Isbell. Springer, New York, [681–706].

- Druc, Isabelle C. 2004 "Ceramic Diversity in Chavín De Huantar, Peru". Latin American Antiquity 15(3), [344–363].

- Kanåo, Chiaki. 1979 The Origins of the Chavin Culture. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.

- Kembel, Silvia Rodriquez and John W. Rick. 2004 Building Authority at Chavin de Huantar: Models of Social Organization and Development in the Initial Period and Early Horizon. In Andean Archaeology. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing.

- Lothrop, S. K. "Gold Artifacts of Chavin Style" Society for American Anthropology 16, 3 (1951), [226–240].

- Mann, Charles C. (July 2011). "Writing, Wheels, and Bucket Brigades". 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (2nd ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1.

- Miller, George R. and Richard L. Burger. "Our Father the Cayman, Our Dinner the Llama: Animal Utilization at Chavin de Huantar, Peru", American Antiquity 60, 3 (1995). [421–458]

- Tello, Julio C. "Discovery of the Chavin Culture in Peru", American Antiquity 9, 1 (1943), [135–160], As you can see the Chavin influenced many other civilizations!

- Enter The Jaguar Mike Jay 2005.

External links

- worldhistory.org Ancient History Encyclopedia

- (in Spanish) Peru Cultural website

- Minnesota State University e-museum

- Chavín de Huantar Digital Media Archive (Creative Commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from a Stanford University/CyArk research partnership (see Exploring Chavín de Huantar link above for additional contextual information)

- Chavín Project with a bibliography and external links

- Chavín Culture Archived 2012-02-08 at the Wayback Machine