Champ de Mai

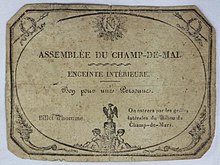

The Champ de Mai ([ʃɑ̃ də mɛ]; "Field of May") was a public assembly held by Napoleon on the Champ de Mars, Paris, a large open area near the École militaire, on 1 June 1815. This was during the Hundred Days, the period between Napoleon's return from exile and the restoration of the Bourbon kings following his failed Waterloo campaign. The objective of the Champ de Mai was to gather public support behind Napoleon's Charter of 1815, a constitutional reform that promised a more liberal government than under his earlier rule. The Charter was put to the citizens in a constitutional referendum and the results of this would be announced during the ceremony by representatives of the electoral college.

Several temporary structures were constructed including a semi-amphitheatre, housing 9–10,000 military and civic dignitaries; a throne platform for Napoleon and his brothers; and a religious altar and a platform from which Napoleon was to distribute imperial eagles, the French standards, to his troops. Around 200,000 spectators attended the event which included a parade of 25,000 soldiers and 25,000 National Guardsmen.

After a Catholic mass, the results of the referendum, a landslide in favour, were announced. Napoleon afterwards signed the Charter and swore, on a copy of the New Testament, that he would uphold it. The distribution of standards overran and those of the National Guard had to be distributed at the Louvre three days later.

Background

Since his defeat by the Sixth Coalition in May 1814 the former French Emperor Napoleon had been exiled to the island of Elba off the coast of Tuscany. His Empress Marie Louise and their son Napoleon (the former King of Rome) had been taken to Austria, where Marie Louise had a lover. The Bourbon line were restored as kings of France.[1] The Bourbons refused to pay Napoleon's stipend, which left him unable to maintain his position in Elba, and, knowing the unpopularity of King Louis XVIII, Napoleon left Elba on 1 March 1815 to regain his position in France. Landing with a small force he marched northwards, rallying French troops to his cause and entering Paris on 20 March.[1]

Napoleon had the support of the French army but was less popular among the general populace; according to Dawson (2017) only 3% supported him.[2] Seeking to improve his position, Napoleon proposed the Charter of 1815, which was similar to the constitution of Louis XVIII. The Charter, also known as the acte additionnel as it was considered merely an amendment to Napoleon's previous constitutions, was written to appeal to liberals and conservatives alike. It contained a bill of rights similar to those of the French Republic and an expanded electorate while reserving power for the propertied classes through a Chamber of Peers. Napoleon's long-term plans are unclear as to whether he intended to rule through the Charter as a constitutional monarch or would renege on it and return to a dictatorship.[3] In the short term, to cement public support, he proposed a grand ceremony in Paris to sign the charter, following its approval by referendum.[4]

Assembly

The assembly was planned to take place in May on the Champ de Mars, a stretch of open ground running from the military school at the École Militaire to the banks of the River Seine.[4] The site had a long association with public assemblies; new laws had been promulgated there since the time of the early French monarchs and, in 1790 during the Fête de la Fédération, Louis XVI had sworn to upload the post-revolutionary constitution.[5] The Champ de Mars also had a long association with Napoleon; a festival was held there in 1793 to celebrate the young Captain Bonaparte's victory at the Siege of Toulon and Napoleon had distributed imperial eagles, the standards of his regiments, to the troops there on the day after his coronation as emperor.[6] Napoleon announced the assembly on 30 April and the members of the electoral college (representatives of the arondissements and departments) were called to meet at Paris.[7] The ceremony was to have taken place in May, hence the name (Mai is French for May), but was delayed until 1 June.[8][9]

The republican faction had wanted Napoleon to appear at the event only as a general, not as an emperor.[10] Napoleon considered this but decided it would not suit his authority and styled the event after his coronation.[10][11] This alienated some of the faction, who saw him only as a means of ridding France of the Bourbons.[10] A large semi-circular platform was erected in front of the military school, accessible by two bridges from the first floor of the building and approached by two flights of stairs.[10] Atop this platform sat a gilded throne for the emperor from which he could look out upon a semi-circular amphitheatre that would provide seating for 9–10,000 civil and military officers, magistrates, elected members of the house of representatives and the deputies of the electoral college.[9][10][12] Seats were provided next to the throne for Napoleon's brothers.[10] An altar was erected in the centre of the Champ de Mars for the religious portion of the ceremony.[4]

Napoleon travelled in formal procession to the ceremony. His coronation carriage, drawn by eight horses, was preceded by his mounted princes, and escorted by marshals of the Empire, including Michel Ney.[10] Napoleon wore silk robes, with a purple cloak, embroidered in gold with ermine trim and his imperial mantle. On his head he wore a black bicorne with a plume of feathers held in place by a large diamond.[10][9] The procession travelled via the Tuileries Garden, the Champs-Élysées and the Pont d'Iéna, through streets lined with citizens.[10] The embankments along the Champ de Mars were crowded with 200,000 onlookers.[5][13] Paraded in the Champ de Mars were, on one side, 25,000 National Guardsmen and, on the other side, 25,000 soldiers of the Imperial Guard and VI Corps together with 100 artillery pieces.[10][12]

After arriving, to the sound of soldiers cheering "Vive L'Empereur", Napoleon entered the École militaire from the rear and emerged onto the throne platform.[10] From the altar platform the Archbishop of Tours Louis-Mathias, Count de Barral led a service of mass after which the "Te Deum" was sung. Five hundred of the electoral college deputies then advanced from the amphitheatre to the throne upon which their spokesperson spoke of the loyalty to Napoleon, hatred towards the foreign armies massing against France and their wishes for a firm and liberal government.[12] The college's arch-chancellor then announced the results of the referendum: 1.3 million votes in favour with only 4,206 against. The Charter was presented to Napoleon who signed it before making a speech denouncing the members of the Seventh Coalition who he said wanted to annex Northern France to the Netherlands and split off the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. The Archbishop of Bourges provided a copy of the New Testament which Napoleon used to swear that he would observe the Charter. Afterwards the crowd cried out "Vive L'Empereur" and also "Vive l'Impératrice" and "Vive le Roi de Rome".[14]

Napoleon then advanced to a separate platform, decorated with trophies of French victories, from which he distributed new eagles to his regiments.[10] The ceremony overran and the distribution of National Guard standards had to be postponed, it took place at the Louvre on 4 June. At the close of the Champ de Mai the military troops marched, in quickstep, off the field to cries of "Vive L'Empereur".[15]

Afterward

The success or otherwise of the Charter to regulate a Napoleonic constitutional monarchy would not be determined. Seven days after the Champ de Mai the Imperial Guard marched out of Paris for the Belgian border to face France's enemies; Napoleon followed them on 12 June.[2] With Russian and Austrian armies en route to reinforce the Coalition, Napoleon crossed the border, seeking to defeat the Anglo-Dutch-Belgian and Prussian armies assembled there. Despite some success, he was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and retreated to Paris. Here he was forced to abdicate by parliament on June 22 and afterwards surrendered himself to British protection. Napoleon lived out his final years in exile on the remote Atlantic island of Saint Helena.[1]

The Champ de Mars remained important to the French. It was the scene of military demonstrations and parades under the restored Bourbon kings. It was afterwards used for horse races and, during the Second French Empire, was again used for the distribution of imperial eagles to French regiments.[16] It was later the site of Expositions Universelles (world's fairs), including the 1889 exposition which saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower on the site.[17]

References

- ^ a b c "Napoleon I - Downfall and abdication". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b Dawson, Paul L. (2017). Napoleon and Grouchy: The Last Great Waterloo Mystery Unravelled. Pen and Sword. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-5267-0069-8.

- ^ Esdaile, Charles (2016). Napoleon, France and Waterloo: The Eagle Rejected. Pen and Sword. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-4738-7084-0.

- ^ a b c Siborne, Captain William (2011). History Of The War In France And Belgium In 1815. 3rd Edition. Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 692. ISBN 978-1-908692-15-3.

- ^ a b Galignani, A.; Galignani, W. (1838). Galignani's New Paris Guide. A. and W. Galignani and Company. p. 341.

- ^ Edwards, Henry Sutherland (1893). Old and New Paris: Its History, its People and its Places (Complete). Library of Alexandria. p. 377. ISBN 978-1-4655-8126-6.

- ^ Collins, Irene (1979). Napoleon and His Parliaments, 1800-1815. Edward Arnold. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-7131-6216-5.

- ^ Hooper, George (1862). Waterloo, the downfall of the first Napoleon. Smith, Elder And Company. p. 28.

- ^ a b c Noel, Jean Auguste (2005). With Napoleon's Guns: The Military Memoirs of an Officer of the First Empire. Frontline Books. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-85367-642-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Thiers, Adolphe (1865). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon. Lippincott. p. 552.

- ^ Thiers, Adolphe (1894). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon. J.B. Lippincott. p. 463.

- ^ a b c Thiers, Adolphe (1865). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon. Lippincott. p. 553.

- ^ Knight, Charles (1862). The Popular History of England: an Illustrated History of Society and Government from the Earliest Period to Our Own Time. Bradbury. p. 27.

- ^ Thiers, Adolphe (1865). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon. Lippincott. p. 554.

- ^ Thiers, Adolphe (1865). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon. Lippincott. p. 555.

- ^ Edwards, Henry Sutherland (1893). Old and New Paris: Its History, its People and its Places (Complete). Library of Alexandria. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-1-4655-8126-6.

- ^ Exposition Universelle, 1900: The Chefs-d'œuvre. G. Barrie & Son. 1900. pp. 15–18.