Augustin-Louis Cauchy

Augustin-Louis Cauchy | |

|---|---|

Cauchy around 1840. Lithography by Zéphirin Belliard after a painting by Jean Roller. | |

| Born | 21 August 1789 |

| Died | 23 May 1857 (aged 67) |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées |

| Known for | Civil engineering Mathematical analysis Gradient descent Implicit function theorem Intermediate value theorem Spectral theorem Limit (mathematics) See full list |

| Spouse | Aloise de Bure |

| Children | Marie Françoise Alicia, Marie Mathilde |

| Awards | Grand Prize of L'Académie Royale des Sciences |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, physics |

| Institutions | École Centrale du Panthéon École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées École Polytechnique |

| Doctoral students | Francesco Faà di Bruno Viktor Bunyakovsky |

Baron Augustin-Louis Cauchy FRS FRSE (UK: /ˈkoʊʃi/ KOH-shee, /ˈkaʊʃi / KOW-shee,[1][2] US: /koʊˈʃiː / koh-SHEE;[2][3] French: [oɡystɛ̃ lwi koʃi]; 21 August 1789 – 23 May 1857) was a French mathematician, engineer, and physicist. He was one of the first to rigorously state and prove the key theorems of calculus (thereby creating real analysis), pioneered the field complex analysis, and the study of permutation groups in abstract algebra. Cauchy also contributed to a number of topics in mathematical physics, notably continuum mechanics.

A profound mathematician, Cauchy had a great influence over his contemporaries and successors;[4] Hans Freudenthal stated:

- "More concepts and theorems have been named for Cauchy than for any other mathematician (in elasticity alone there are sixteen concepts and theorems named for Cauchy)."[5]

Cauchy was a prolific worker; he wrote approximately eight hundred research articles and five complete textbooks on a variety of topics in the fields of mathematics and mathematical physics.

Biography

Youth and education

Cauchy was the son of Louis François Cauchy (1760–1848) and Marie-Madeleine Desestre. Cauchy had two brothers: Alexandre Laurent Cauchy (1792–1857), who became a president of a division of the court of appeal in 1847 and a judge of the court of cassation in 1849, and Eugene François Cauchy (1802–1877), a publicist who also wrote several mathematical works. From his childhood he was good at math.

Cauchy married Aloise de Bure in 1818. She was a close relative of the publisher who published most of Cauchy's works. They had two daughters, Marie Françoise Alicia (1819) and Marie Mathilde (1823).

Cauchy's father was a highly ranked official in the Parisian police of the Ancien Régime, but lost this position due to the French Revolution (14 July 1789), which broke out one month before Augustin-Louis was born.[a] The Cauchy family survived the revolution and the following Reign of Terror during 1793–94 by escaping to Arcueil, where Cauchy received his first education, from his father.[6] After the execution of Robespierre in 1794, it was safe for the family to return to Paris. There, Louis-François Cauchy found a bureaucratic job in 1800,[7] and quickly advanced his career. When Napoleon came to power in 1799, Louis-François Cauchy was further promoted, and became Secretary-General of the Senate, working directly under Laplace (who is now better known for his work on mathematical physics). The mathematician Lagrange was also a friend of the Cauchy family.[4]

On Lagrange's advice, Augustin-Louis was enrolled in the École Centrale du Panthéon, the best secondary school of Paris at that time, in the fall of 1802.[6] Most of the curriculum consisted of classical languages; the ambitious Cauchy, being a brilliant student, won many prizes in Latin and the humanities. In spite of these successes, Cauchy chose an engineering career, and prepared himself for the entrance examination to the École Polytechnique.

In 1805, he placed second of 293 applicants on this exam and was admitted.[6] One of the main purposes of this school was to give future civil and military engineers a high-level scientific and mathematical education. The school functioned under military discipline, which caused Cauchy some problems in adapting. Nevertheless, he completed the course in 1807, at age 18, and went on to the École des Ponts et Chaussées (School for Bridges and Roads). He graduated in civil engineering, with the highest honors.

Engineering days

After finishing school in 1810, Cauchy accepted a job as a junior engineer in Cherbourg, where Napoleon intended to build a naval base. Here Cauchy stayed for three years, and was assigned the Ourcq Canal project and the Saint-Cloud Bridge project, and worked at the Harbor of Cherbourg.[6] Although he had an extremely busy managerial job, he still found time to prepare three mathematical manuscripts, which he submitted to the Première Classe (First Class) of the Institut de France.[b] Cauchy's first two manuscripts (on polyhedra) were accepted; the third one (on directrices of conic sections) was rejected.

In September 1812, at 23 years old, Cauchy returned to Paris after becoming ill from overwork.[6] Another reason for his return to the capital was that he was losing interest in his engineering job, being more and more attracted to the abstract beauty of mathematics; in Paris, he would have a much better chance to find a mathematics related position. When his health improved in 1813, Cauchy chose not to return to Cherbourg.[6] Although he formally kept his engineering position, he was transferred from the payroll of the Ministry of the Marine to the Ministry of the Interior. The next three years Cauchy was mainly on unpaid sick leave; he spent his time fruitfully, working on mathematics (on the related topics of symmetric functions, the symmetric group and the theory of higher-order algebraic equations). He attempted admission to the First Class of the Institut de France but failed on three different occasions between 1813 and 1815. In 1815 Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo, and the newly installed king Louis XVIII took the restoration in hand. The Académie des Sciences was re-established in March 1816; Lazare Carnot and Gaspard Monge were removed from this academy for political reasons, and the king appointed Cauchy to take the place of one of them. The reaction of Cauchy's peers was harsh; they considered the acceptance of his membership in the academy an outrage, and Cauchy created many enemies in scientific circles.

Professor at École Polytechnique

In November 1815, Louis Poinsot, who was an associate professor at the École Polytechnique, asked to be exempted from his teaching duties for health reasons. Cauchy was by then a rising mathematical star. One of his great successes at that time was the proof of Fermat's polygonal number theorem. He quit his engineering job, and received a one-year contract for teaching mathematics to second-year students of the École Polytechnique. In 1816, this Bonapartist, non-religious school was reorganized, and several liberal professors were fired; Cauchy was promoted to full professor.

When Cauchy was 28 years old, he was still living with his parents. His father found it time for his son to marry; he found him a suitable bride, Aloïse de Bure, five years his junior. The de Bure family were printers and booksellers, and published most of Cauchy's works.[8] Aloïse and Augustin were married on April 4, 1818, with great Roman Catholic ceremony, in the Church of Saint-Sulpice. In 1819 the couple's first daughter, Marie Françoise Alicia, was born, and in 1823 the second and last daughter, Marie Mathilde.[9]

The conservative political climate that lasted until 1830 suited Cauchy perfectly. In 1824 Louis XVIII died, and was succeeded by his even more conservative brother Charles X. During these years Cauchy was highly productive, and published one important mathematical treatise after another. He received cross-appointments at the Collège de France, and the Faculté des sciences de Paris.

In exile

In July 1830, the July Revolution occurred in France. Charles X fled the country, and was succeeded by Louis-Philippe. Riots, in which uniformed students of the École Polytechnique took an active part, raged close to Cauchy's home in Paris.

These events marked a turning point in Cauchy's life, and a break in his mathematical productivity. Shaken by the fall of the government and moved by a deep hatred of the liberals who were taking power, Cauchy left France to go abroad, leaving his family behind.[10] He spent a short time at Fribourg in Switzerland, where he had to decide whether he would swear a required oath of allegiance to the new regime. He refused to do this, and consequently lost all his positions in Paris, except his membership of the academy, for which an oath was not required. In 1831 Cauchy went to the Italian city of Turin, and after some time there, he accepted an offer from the King of Sardinia (who ruled Turin and the surrounding Piedmont region) for a chair of theoretical physics, which was created especially for him. He taught in Turin during 1832–1833. In 1831, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and the following year a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[11]

In August 1833 Cauchy left Turin for Prague to become the science tutor of the thirteen-year-old Duke of Bordeaux, Henri d'Artois (1820–1883), the exiled Crown Prince and grandson of Charles X.[12] As a professor of the École Polytechnique, Cauchy had been a notoriously bad lecturer, assuming levels of understanding that only a few of his best students could reach, and cramming his allotted time with too much material. Henri d'Artois had neither taste nor talent for either mathematics or science. Although Cauchy took his mission very seriously, he did this with great clumsiness, and with surprising lack of authority over Henri d'Artois. During his civil engineering days, Cauchy once had been briefly in charge of repairing a few of the Parisian sewers, and he made the mistake of mentioning this to his pupil; with great malice, Henri d'Artois went about saying Cauchy started his career in the sewers of Paris. Cauchy's role as tutor lasted until Henri d'Artois became eighteen years old, in September 1838.[10] Cauchy did hardly any research during those five years, while Henri d'Artois acquired a lifelong dislike of mathematics. Cauchy was named a baron, a title by which Cauchy set great store.

In 1834, his wife and two daughters moved to Prague, and Cauchy was reunited with his family after four years in exile.

Last years

Cauchy returned to Paris and his position at the Academy of Sciences late in 1838.[10] He could not regain his teaching positions, because he still refused to swear an oath of allegiance.

In August 1839 a vacancy appeared in the Bureau des Longitudes. This Bureau bore some resemblance to the academy; for instance, it had the right to co-opt its members. Further, it was believed that members of the Bureau could "forget about" the oath of allegiance, although formally, unlike the Academicians, they were obliged to take it. The Bureau des Longitudes was an organization founded in 1795 to solve the problem of determining position at sea — mainly the longitudinal coordinate, since latitude is easily determined from the position of the sun. Since it was thought that position at sea was best determined by astronomical observations, the Bureau had developed into an organization resembling an academy of astronomical sciences.

In November 1839 Cauchy was elected to the Bureau, and discovered that the matter of the oath was not so easily dispensed with. Without his oath, the king refused to approve his election. For four years Cauchy was in the position of being elected but not approved; accordingly, he was not a formal member of the Bureau, did not receive payment, could not participate in meetings, and could not submit papers. Still Cauchy refused to take any oaths; however, he did feel loyal enough to direct his research to celestial mechanics. In 1840, he presented a dozen papers on this topic to the academy. He described and illustrated the signed-digit representation of numbers, an innovation presented in England in 1727 by John Colson. The confounded membership of the Bureau lasted until the end of 1843, when Cauchy was replaced by Poinsot.

Throughout the nineteenth century the French educational system struggled over the separation of church and state. After losing control of the public education system, the Catholic Church sought to establish its own branch of education and found in Cauchy a staunch and illustrious ally. He lent his prestige and knowledge to the École Normale Écclésiastique, a school in Paris run by Jesuits, for training teachers for their colleges. He took part in the founding of the Institut Catholique. The purpose of this institute was to counter the effects of the absence of Catholic university education in France. These activities did not make Cauchy popular with his colleagues, who, on the whole, supported the Enlightenment ideals of the French Revolution. When a chair of mathematics became vacant at the Collège de France in 1843, Cauchy applied for it, but received just three of 45 votes.

In 1848 King Louis-Philippe fled to England. The oath of allegiance was abolished, and the road to an academic appointment was clear for Cauchy. On March 1, 1849, he was reinstated at the Faculté de Sciences, as a professor of mathematical astronomy. After political turmoil all through 1848, France chose to become a Republic, under the Presidency of Napoleon III of France. Early 1852 the President made himself Emperor of France, and took the name Napoleon III.

The idea came up in bureaucratic circles that it would be useful to again require a loyalty oath from all state functionaries, including university professors. This time a cabinet minister was able to convince the Emperor to exempt Cauchy from the oath. In 1853, Cauchy was elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society.[13] Cauchy remained a professor at the university until his death at the age of 67. He received the Last Rites and died of a bronchial condition at 4 a.m. on 23 May 1857.[10]

His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Work

Early work

The genius of Cauchy was illustrated in his simple solution of the problem of Apollonius—describing a circle touching three given circles—which he discovered in 1805, his generalization of Euler's formula on polyhedra in 1811, and in several other elegant problems. More important is his memoir on wave propagation, which obtained the Grand Prix of the French Academy of Sciences in 1816. Cauchy's writings covered notable topics. In the theory of series he developed the notion of convergence and discovered many of the basic formulas for q-series. In the theory of numbers and complex quantities, he was the first to define complex numbers as pairs of real numbers. He also wrote on the theory of groups and substitutions, the theory of functions, differential equations and determinants.[4]

Wave theory, mechanics, elasticity

In the theory of light he worked on Fresnel's wave theory and on the dispersion and polarization of light. He also contributed research in mechanics, substituting the notion of the continuity of geometrical displacements for the principle of the continuity of matter.[14] He wrote on the equilibrium of rods and elastic membranes and on waves in elastic media. He introduced a 3 × 3 symmetric matrix of numbers that is now known as the Cauchy stress tensor.[15] In elasticity, he originated the theory of stress, and his results are nearly as valuable as those of Siméon Poisson.[4]

Number theory

Other significant contributions include being the first to prove the Fermat polygonal number theorem.

Complex functions

Cauchy is most famous for his single-handed development of complex function theory. The first pivotal theorem proved by Cauchy, now known as Cauchy's integral theorem, was the following:

where f(z) is a complex-valued function holomorphic on and within the non-self-intersecting closed curve C (contour) lying in the complex plane. The contour integral is taken along the contour C. The rudiments of this theorem can already be found in a paper that the 24-year-old Cauchy presented to the Académie des Sciences (then still called "First Class of the Institute") on August 11, 1814. In full form the theorem was given in 1825.[16]

In 1826 Cauchy gave a formal definition of a residue of a function.[17] This concept concerns functions that have poles—isolated singularities, i.e., points where a function goes to positive or negative infinity. If the complex-valued function f(z) can be expanded in the neighborhood of a singularity a as

where φ(z) is analytic (i.e., well-behaved without singularities), then f is said to have a pole of order n in the point a. If n = 1, the pole is called simple. The coefficient B1 is called by Cauchy the residue of function f at a. If f is non-singular at a then the residue of f is zero at a. Clearly, the residue is in the case of a simple pole equal to

where we replaced B1 by the modern notation of the residue.

In 1831, while in Turin, Cauchy submitted two papers to the Academy of Sciences of Turin. In the first[18] he proposed the formula now known as Cauchy's integral formula,

where f(z) is analytic on C and within the region bounded by the contour C and the complex number a is somewhere in this region. The contour integral is taken counter-clockwise. Clearly, the integrand has a simple pole at z = a. In the second paper[19] he presented the residue theorem,

where the sum is over all the n poles of f(z) on and within the contour C. These results of Cauchy's still form the core of complex function theory as it is taught today to physicists and electrical engineers. For quite some time, contemporaries of Cauchy ignored his theory, believing it to be too complicated. Only in the 1840s the theory started to get response, with Pierre Alphonse Laurent being the first mathematician besides Cauchy to make a substantial contribution (his work on what are now known as Laurent series, published in 1843).

Cours d'Analyse

In his book Cours d'Analyse Cauchy stressed the importance of rigor in analysis. Rigor in this case meant the rejection of the principle of Generality of algebra (of earlier authors such as Euler and Lagrange) and its replacement by geometry and infinitesimals.[20] Judith Grabiner wrote Cauchy was "the man who taught rigorous analysis to all of Europe".[21] The book is frequently noted as being the first place that inequalities, and arguments were introduced into calculus. Here Cauchy defined continuity as follows: The function f(x) is continuous with respect to x between the given limits if, between these limits, an infinitely small increment in the variable always produces an infinitely small increment in the function itself.

M. Barany claims that the École mandated the inclusion of infinitesimal methods against Cauchy's better judgement.[22] Gilain notes that when the portion of the curriculum devoted to Analyse Algébrique was reduced in 1825, Cauchy insisted on placing the topic of continuous functions (and therefore also infinitesimals) at the beginning of the Differential Calculus.[23] Laugwitz (1989) and Benis-Sinaceur (1973) point out that Cauchy continued to use infinitesimals in his own research as late as 1853.

Cauchy gave an explicit definition of an infinitesimal in terms of a sequence tending to zero. There has been a vast body of literature written about Cauchy's notion of "infinitesimally small quantities", arguing that they lead from everything from the usual "epsilontic" definitions or to the notions of non-standard analysis. The consensus is that Cauchy omitted or left implicit the important ideas to make clear the precise meaning of the infinitely small quantities he used.[24]

Taylor's theorem

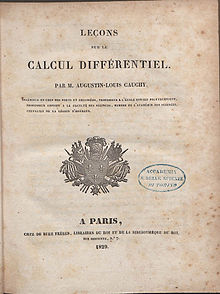

He was the first to prove Taylor's theorem rigorously, establishing his well-known form of the remainder.[4] He wrote a textbook[25] (see the illustration) for his students at the École Polytechnique in which he developed the basic theorems of mathematical analysis as rigorously as possible. In this book he gave the necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a limit in the form that is still taught. Also Cauchy's well-known test for absolute convergence stems from this book: Cauchy condensation test. In 1829 he defined for the first time a complex function of a complex variable in another textbook.[26] In spite of these, Cauchy's own research papers often used intuitive, not rigorous, methods;[27] thus one of his theorems was exposed to a "counter-example" by Abel, later fixed by the introduction of the notion of uniform continuity.

Argument principle, stability

In a paper published in 1855, two years before Cauchy's death, he discussed some theorems, one of which is similar to the "Principle of the argument" in many modern textbooks on complex analysis. In modern control theory textbooks, the Cauchy argument principle is quite frequently used to derive the Nyquist stability criterion, which can be used to predict the stability of negative feedback amplifier and negative feedback control systems. Thus Cauchy's work has a strong impact on both pure mathematics and practical engineering.

Published works

Cauchy was very productive, in number of papers second only to Leonhard Euler. It took almost a century to collect all his writings into 27 large volumes:

- Oeuvres complètes d'Augustin Cauchy publiées sous la direction scientifique de l'Académie des sciences et sous les auspices de M. le ministre de l'Instruction publique (27 volumes) at the Wayback Machine (archived July 24, 2007)(Paris : Gauthier-Villars et fils, 1882–1974)

- Œuvres complètes d'Augustin Cauchy. Académie des sciences (France). 1882–1938 – via Ministère de l'éducation nationale.

His greatest contributions to mathematical science are enveloped in the rigorous methods which he introduced; these are mainly embodied in his three great treatises:

- "Analyse Algébrique". Cours d'analyse de l'École royale polytechnique. Paris: L'Imprimerie Royale, Debure frères, Libraires du Roi et de la Bibliothèque du Roi. 1821. online at the Internet Archive.

- Le Calcul infinitésimal (1823)

- Leçons sur les applications de calcul infinitésimal; La géométrie (1826–1828)[4]

His other works include:

- Mémoire sur les intégrales définies, prises entre des limites imaginaires [A Memorandum on definite integrals taken between imaginary limits] (in French). submitted to the Académie des Sciences on February 28: Paris, De Bure frères. 1825.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Exercices de mathematiques. Paris. 1826.

- Exercices de mathematiques. Vol. Seconde Année. Paris. 1827.

- Leçons sur le calcul différentiel. Paris: De Bure frères. 1829.

- Sur la mecanique celeste et sur un nouveau calcul qui s'applique a un grand nombre de questions diverses etc [On Celestial Mechanics and on a new calculation which is applicable to a large number of diverse questions] (in French). presented to the Academy of Sciences of Turin, October 11. 1831.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Exercices d'analyse et de physique mathematique (Volume 1)

- Exercices d'analyse et de physique mathematique (Volume 2)

- Exercices d'analyse et de physique mathematique (Volume 3)

- Exercices d'analyse et de physique mathematique (Volume 4) (Paris: Bachelier, 1840–1847)

- Analyse algèbrique (Imprimerie Royale, 1821)

- Nouveaux exercices de mathématiques (Paris : Gauthier-Villars, 1895)

- Courses of mechanics (for the École Polytechnique)

- Higher algebra (for the Faculté des sciences de Paris)

- Mathematical physics (for the Collège de France).

- Mémoire sur l'emploi des equations symboliques dans le calcul infinitésimal et dans le calcul aux différences finis CR Ac ad. Sci. Paris, t. XVII, 449–458 (1843) credited as originating the operational calculus.

Politics and religious beliefs

Augustin-Louis Cauchy grew up in the house of a staunch royalist. This made his father flee with the family to Arcueil during the French Revolution. Their life there during that time was apparently hard; Augustin-Louis's father, Louis François, spoke of living on rice, bread, and crackers during the period. A paragraph from an undated letter from Louis François to his mother in Rouen says:[28]

We never had more than a one-half pound (230 g) of bread — and sometimes not even that. This we supplement with little supply of hard crackers and rice that we are allotted. Otherwise, we are getting along quite well, which is the important thing and goes to show that human beings can get by with little. I should tell you that for my children's pap I still have a bit of fine flour, made from wheat that I grew on my own land. I had three bushels, and I also have a few pounds of potato starch. It is as white as snow and very good, too, especially for very young children. It, too, was grown on my own land.[29]

In any event, he inherited his father's staunch royalism and hence refused to take oaths to any government after the overthrow of Charles X.

He was an equally staunch Catholic and a member of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul.[30] He also had links to the Society of Jesus and defended them at the academy when it was politically unwise to do so. His zeal for his faith may have led to his caring for Charles Hermite during his illness and leading Hermite to become a faithful Catholic. It also inspired Cauchy to plead on behalf of the Irish during the Great Famine of Ireland.

His royalism and religious zeal made him contentious, which caused difficulties with his colleagues. He felt that he was mistreated for his beliefs, but his opponents felt he intentionally provoked people by berating them over religious matters or by defending the Jesuits after they had been suppressed. Niels Henrik Abel called him a "bigoted Catholic"[31] and added he was "mad and there is nothing that can be done about him", but at the same time praised him as a mathematician. Cauchy's views were widely unpopular among mathematicians and when Guglielmo Libri Carucci dalla Sommaja was made chair in mathematics before him he, and many others, felt his views were the cause. When Libri was accused of stealing books he was replaced by Joseph Liouville rather than Cauchy, which caused a rift between Liouville and Cauchy. Another dispute with political overtones concerned Jean-Marie Constant Duhamel and a claim on inelastic shocks. Cauchy was later shown, by Jean-Victor Poncelet, to be wrong.

See also

- List of topics named after Augustin-Louis Cauchy

- Cauchy–Binet formula

- Cauchy boundary condition

- Cauchy's convergence test

- Cauchy (crater)

- Cauchy determinant

- Cauchy distribution

- Cauchy's equation

- Cauchy–Euler equation

- Cauchy's functional equation

- Cauchy horizon

- Cauchy formula for repeated integration

- Cauchy–Frobenius lemma

- Cauchy–Hadamard theorem

- Cauchy–Kovalevskaya theorem

- Cauchy momentum equation

- Cauchy–Peano theorem

- Cauchy principal value

- Cauchy problem

- Cauchy product

- Cauchy's radical test

- Cauchy–Rassias stability

- Cauchy–Riemann equations

- Cauchy–Schwarz inequality

- Cauchy sequence

- Cauchy surface

- Cauchy's theorem (geometry)

- Cauchy's theorem (group theory)

- Maclaurin–Cauchy test

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003). Roach, Peter; Hartman, James; Setter, Jane (eds.). "Cauchy". Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (16th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-521-81693-9.

- ^ a b "Cauchy". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ "Cauchy". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary – via dictionary.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Freudenthal 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Bruno & Baker 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Bruno & Baker 2003, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Bradley & Sandifer 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Belhoste 1991, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d Bruno & Baker 2003, p. 67.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter C" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Bruno & Baker 2003, p. 68.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ Kurrer, K.-E. (2018). The History of the Theory of Structures. Searching for Equilibrium. Berlin: Wiley. pp. 978–979. ISBN 978-3-433-03229-9.

- ^ Cauchy 1827, p. 42, "De la pression ou tension dans un corps solide" [On pressure or tension in a solid body].

- ^ Cauchy 1825.

- ^ Cauchy 1826, p. 11, "Sur un nouveau genre de calcul analogue au calcul infinitésimal" [On a new type of calculus analogous to the infinitesimal calculus].

- ^ Cauchy 1831.

- ^ Cauchy, Mémoire sur les rapports qui existent entre le calcul des Résidus et le calcul des Limites, et sur les avantages qu'offrent ces deux calculs dans la résolution des équations algébriques ou transcendantes (Memorandum on the connections that exist between the residue calculus and the limit calculus, and on the advantages that these two calculi offer in solving algebraic and transcendental equations], presented to the Academy of Sciences of Turin, November 27, 1831.

- ^ Borovik & Katz 2012, pp. 245–276.

- ^ Grabiner 1981.

- ^ Barany 2011.

- ^ Gilain 1989.

- ^ Barany 2013.

- ^ Cauchy 1821.

- ^ Cauchy 1829.

- ^ Kline 1982, p. 176.

- ^ Valson 1868, p. 13, Vol. 1.

- ^ Belhoste 1991, p. 3.

- ^ Brock 1908.

- ^ Bell 1986, p. 273.

Sources

- Belhoste, Bruno (1991). Augustin-Louis Cauchy: A Biography. Translated by Frank Ragland. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Springer. p. 134. ISBN 3-540-97220-X.

- Bell, E. T. (1986). Men of Mathematics. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671628185.

- Borovik, Alexandre; Katz, Mikhail G. (2012). "Who gave you the Cauchy--Weierstrass tale? The dual history of rigorous calculus". Foundations of Science. 17 (3): 245–276. arXiv:1108.2885. doi:10.1007/s10699-011-9235-x. S2CID 119320059.

- Bradley, Robert E.; Sandifer, Charles Edward (2010). Buchwald, J. Z. (ed.). Cauchy's Cours d'analyse: An Annotated Translation. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. Cauchy, Augustin-Louis. Springer. pp. 10, 285. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0549-9. ISBN 978-1-4419-0548-2. LCCN 2009932254.

- Brock, Henry Matthias (1908). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Bruno, Leonard C.; Baker, Lawrence W. (2003) [1999]. Math and mathematicians : the history of math discoveries around the world. Detroit, Mich.: U X L. ISBN 0787638137. OCLC 41497065.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 555–556.

- Freudenthal, Hans (2008). "Cauchy, Augustin-Louis". In Gillispie, Charles (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9 – via American Council of Learned Societies.

- Kline, Morris (1982). Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503085-3.

- Valson, Claude-Alphonse (1868). La vie et les travaux du baron Cauchy: membre de l'académie des sciences [The Life and Works of Baron Cauchy: Member of the Academy of Scinces] (in French). Gauthier-Villars.

- This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Augustin-Louis Cauchy", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

Further reading

- Barany, Michael (2013), "Stuck in the Middle: Cauchy's Intermediate Value Theorem and the History of Analytic Rigor", Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 60 (10): 1334–1338, doi:10.1090/noti1049

- Barany, Michael (2011), "God, king, and geometry: revisiting the introduction to Cauchy's Cours d'analyse", Historia Mathematica, 38 (3): 368–388, doi:10.1016/j.hm.2010.12.001

- Boyer, C.: The concepts of the calculus. Hafner Publishing Company, 1949.

- Benis-Sinaceur, Hourya (1973). "Cauchy et Bolzano" (PDF). Revue d'Histoire des Sciences. 26 (2): 97–112. doi:10.3406/rhs.1973.3315. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Laugwitz, D. (1989), "Definite values of infinite sums: aspects of the foundations of infinitesimal analysis around 1820", Arch. Hist. Exact Sci., 39 (3): 195–245, doi:10.1007/BF00329867, S2CID 120890300.

- Gilain, C. (1989), "Cauchy et le Course d'Analyse de l'École Polytechnique", Bulletin de la Société des amis de la Bibliothèque de l'École polytechnique, 5: 3–145

- Grabiner, Judith V. (1981). The Origins of Cauchy's Rigorous Calculus. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-387-90527-8.

- Rassias, Th. M. (1989). Topics in Mathematical Analysis, A Volume Dedicated to the Memory of A. L. Cauchy. Singapore, New Jersey, London: World Scientific Co. Archived from the original on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- Smithies, F. (1986). "Cauchy's Conception of Rigour in Analysis". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 36 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1007/BF00357440. JSTOR 41133794. S2CID 120781880.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

External links

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Augustin-Louis Cauchy", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Cauchy criterion for convergence at the Wayback Machine (archived June 17, 2005)

- Augustin-Louis Cauchy – Œuvres complètes (in 2 series) Gallica-Math

- Augustin-Louis Cauchy at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Augustin-Louis Cauchy – Cauchy's Life by Robin Hartshorne