Cagliari

Cagliari Casteddu (Sardinian) | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Cagliari | |

Bastione of Saint Remy; Marina Piccola; View of Castello; Basilica of San Saturnino; City Hall; Basilica of Bonaria; View of the Poetto beach; View of Monte Claro park; View of Molentargius park | |

| Coordinates: 39°13′40″N 09°06′40″E / 39.22778°N 9.11111°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Sardinia |

| Metropolitan city | Cagliari (CA) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Massimo Zedda (Progressive Party) |

| Area | |

• Total | 85.45 km2 (32.99 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Population (2015)[2] | |

• Total | 154,460 |

| • Density | 1,800/km2 (4,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 09100 |

| Dialing code | 070 |

| ISTAT code | 092009 |

| Patron saint | St. Saturninus |

| Saint day | 30 October |

| Website | Official website |

Cagliari (/kælˈjɑːri/, also UK: /ˌkæliˈɑːri, ˈkæljəri/, US: /ˈkɑːljəri/;[3][4][5][6] Italian: [ˈkaʎʎari] ; Sardinian: Casteddu [kasˈteɖːu];[a] Latin: Caralis) is an Italian municipality and the capital and largest city of the island of Sardinia, an autonomous region of Italy.[7] It has about 155,000 inhabitants,[8] while its metropolitan city (including Cagliari and 16 other nearby municipalities) has about 420,000 inhabitants. According to Eurostat, the population of the functional urban area, the commuting zone of Cagliari, rises to 476,975.[9] Cagliari is the 26th largest city in Italy and the largest city on the island of Sardinia.

An ancient city with a long history, Cagliari has seen the rule of several civilisations. Under the buildings of the modern city there is a continuous stratification attesting to human settlement over the course of some five thousand years, from the Neolithic to today. Historical sites include the prehistoric Domus de Janas, very damaged by cave activity, a large Carthaginian era necropolis, a Roman era amphitheatre, a Byzantine basilica, three Pisan-era towers and a strong system of fortification that made the town the core of Spanish Habsburg imperial power in the western Mediterranean Sea. Its natural resources have always been its sheltered harbour, the often powerfully fortified hill of Castel di Castro, the modern Casteddu, the salt from its lagoons, and, from the hinterland, wheat from the Campidano plain and silver and other ores from the Iglesiente mines.

Cagliari was the capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia from 1324 to 1848, when Turin became the formal capital of the kingdom (which in 1861 became the Kingdom of Italy). Today the city is a regional cultural, educational, political and artistic centre, known for its diverse Art Nouveau architecture and several monuments.[10] It is also Sardinia's economic and industrial hub, having one of the biggest ports in the Mediterranean Sea, an international airport, and the 106th highest income level in Italy (among 8,092 comuni), comparable to that of several northern Italian cities.[11]

It is also the seat of the University of Cagliari,[12] founded in 1607, and of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cagliari,[13][14] since the 5th century AD.

History

Early history

The Cagliari area has been inhabited since the Neolithic. It occupies a favourable position between the sea and a fertile plain and is surrounded by two marshes (which provides defence against attacks from the inland). There are high mountains nearby, to which people could evacuate if the settlement had to be given up. Relics of prehistoric inhabitants were found in the hill of Monte Claro (Monte Claro culture) and in Cape Sant'Elia (several domus de janas).

Karaly (Punic: 𐤊𐤓𐤋𐤉, KRLY)[15] was established around the 8th/7th century BC as one of a string of Phoenician colonies in Sardinia, including Tharros.[16] The etymology of the toponym is unknown. It almost certainly does not come from the Phoenician language, but it has some similarities with other Sardinian or Asia Minor toponyms.[17] Its founding is linked to its position along communication routes with Africa as well as to its excellent port. The Phoenician settlement was located in the Stagno di Santa Gilla, west of the present centre of Cagliari. This was also the site of the Roman Portus Scipio, and when Arab pirates raided the area in the 8th century it became the refuge for people fleeing from the city. Other Phoenician settlements have been found at Cape Sant'Elia.

In the late 6th century BC Carthage took control of part of Sardinia, and Cagliari grew substantially under its domination, as testified by the large Tuvixeddu necropolis and other remains. Cagliari was a fortified settlement in what is now the modern Marina quarter, with an annexed holy area in the modern Stampace.

Sardinia and Cagliari came under Roman rule in 238 BC, shortly after the First Punic War, when the Romans defeated the Carthaginians. No mention of it is found on the occasion of the Roman conquest of the island but, during the Second Punic War, Caralis was the headquarters of the praetor, Titus Manlius Torquatus, whence he conducted his operations against Hampsicora and the Carthaginians.[18] At other times it was also the Romans' chief naval station on the island and the residence of its praetor.[19]

The Romans built a new settlement east of the old Punic city, the vicus munitus Caralis (i.e. the fortified community of Caralis) mentioned by Varro Atacinus. The two urban agglomerations merged gradually during the second century BC; to this process is perhaps attributable the plural name Carales.[20]

Florus calls it the urbs urbium or capital of Sardinia. He represents it as taken and severely punished by Gracchus,[21] but this statement is wholly at variance with Livy's account of the wars of Gracchus, in Sardinia, according to which the cities were faithful to Rome, and the revolt was confined to the mountain tribes.[22] In the Civil War between Caesar and Pompey, the citizens of Caralis were the first to declare in favor of the former, an example soon followed by the other cities of Sardinia;[23] and Caesar himself touched there with his fleet on his return from Africa.[24] A few years later, when Sardinia fell into the hands of Menas, the lieutenant of Sextus Pompeius, Caralis was the only city which offered any resistance, but was taken after a short siege.[25]

Cagliari continued to be regarded as the capital of the island under the Roman Empire, and though it did not become a colony, obtained the status of municipium.[26]

Remains of Roman public buildings were found to the west of Marina in Piazza del Carmine. There was an area of ordinary housing near the modern Via Roma, and richer houses on the slopes of the Marina distinct. The amphitheatre is located to the west of the Castello.

A Christian community is attested in Cagliari at least as early as the 3rd century, and by the end of that century the city had a Christian bishop. In the middle decades of the 4th century bishop Lucifer of Cagliari was exiled because of his opposition to the sentence against Athanasius of Alexandria at the Synod of Milan. He was banished to the desert of Thebais by the emperor Constantius II.[27]

Claudian describes the ancient city of Karalis as extending to a considerable length towards the promontory or headland, the projection of which sheltered its port. The port affords good anchorage for large vessels, but besides this, which is only a well-sheltered standby, there is a large salt-water lake or lagoon, called the Stagno di Cagliari, adjoining the city and communicating by a narrow channel with the bay, which appears from Claudian to have been used in ancient times as an inner harbor or basin.[28] The promontory adjoining the city is evidently that noticed by Ptolemy (Κάραλις πόλις καὶ ἄκρα), but the Caralitanum Promontorium of Pliny can be no other than the headland, now called Capo Carbonara, which forms the eastern boundary of the Gulf of Cagliari and the southeast point of the whole island. Immediately off it lay the little island of Ficaria,[29] now called the Isola dei Cavoli ("Cabbage Island" in Italian, Isula de is Càvurus "Crab Island" in Sardinian).

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire Cagliari fell, together with the rest of Sardinia, into the hands of the Vandals, but appears to have retained its importance throughout the Middle Ages.

Judicate of Cagliari

Subsequently, ruled by the Vandals, Ostrogoths, and then part of the Byzantine Empire, Cagliari became the capital of a gradually independent Judicate, (from Latin Iudex, Governor and Supreme Magistrate, used in late Roman and Byzantine period, along with the medieval Greek ἄρχων). This state was born around 1020 and was overthrown by the Republic of Pisa in 1258. Due to the overlap of buildings since the year 800 B.C., and the scarcity of archeological and historical informations, it was believed that the population was moved to more inland areas of the territory, along the lagoon, in a city called Santa Ilia or Santa Igia (modern San Gilla) and it was believed that the ancient Roman and Byzantine city had been abandoned because it was too exposed to attacks by Moorish pirates coming from north Africa and Spain. Recent studies have instead hypothesized that the capital of the Giudicato was located around the road that it directed towards Sassari, today called Corso Vittorio Emanuele II (in Sardinian language: Su Brugu, the borough), although there are not yet archeological confirmations, particularly of the Cathedral and the Judex Palace, destroyed after the Pisan conquest.[30][31] The Judicate of Cagliari comprised a large area of the Campidano plain, the Sulcis-Iglesiente and the mountain region of Ogliastra.

11th to 13th century

During the 11th century, the Republic of Pisa began to extend its political influence over the Judgedom of Cagliari. Pisa and the maritime republic of Genoa had a keen interest in Sardinia because it was a perfect strategic base for controlling the commercial routes between Italy and North Africa.

In 1215 the Pisan Lamberto Visconti, husband of Elena of Gallura, forced the judikessa Benedetta of Cagliari to give him the mount located east of Santa Igia.[32] Soon (1216–17) Pisan merchants established there a new fortified city, known as Castel di Castro, which can be considered the ancestor of the modern city of Cagliari.[32]

In 1258, after the defeat of William III, the last king of Cagliari, the Pisans and their Sardinian allies (Arborea, Gallura and Logudoro) destroyed the old capital of Santa Igia.[32] The Judgedom of Cagliari was then divided into three parts: the northeast third went to Gallura; the central portion was incorporated into Arborea; Sulcis and Iglesiente, on the southwest, were given to the Pisan della Gherardesca family, while the Republic of Pisa maintained control over its colony of Castel di Castro.[33]

Some of the fortifications that still surround the current district of Castello were built by the Pisans, including the two remaining white limestone towers (early 14th century) designed by the architect Giovanni Capula. Together with the district of Castello, Castel di Castro comprised the districts of Marina (which included the port), and later Stampace and Villanova. Marina and Stampace were guarded by walls, in contrast to Villanova, which was mostly home to peasants.

14th to 17th centuries

In the second decade of the 14th century the Crown of Aragon conquered Sardinia after a series of battles against the Pisans. During the siege of Castel di Castro (1324-1326), the Aragonese, led by Alfonso IV of Aragon, built a stronghold on a more southern hill, that of Bonaria.

When the fortified city was finally conquered by the Aragonese army, Castel di Castro (Castel de Càller or simply Càller in Catalan) became the administrative capital of the newborn Kingdom of Sardinia, one of the many kingdoms forming the Crown of Aragon, which later came under the rule of the Spanish Empire. After the expulsion of the Tuscans,[34] the Castello district was repopulated by the Aragonese settlers of Bonaria while the indigenous population was, as in the past, concentrated in Stampace and Villanova.

The kings of Sardinia, also kings of Aragon and later kings of Spain, were represented in Cagliari by a viceroy, who resided in the Palazzo Regio.

In the 16th century the fortifications of the city were strengthened with the construction of the bastions and the rights and benefits of the Aragonese were extended to all citizens. The intellectual life was relatively lively and in the early years of the 17th century the university was founded.

18th century

In 1718,[35] after a brief rule by the Habsburgs, Cagliari and Sardinia came under the House of Savoy. As rulers of Sardinia, the Savoys took the title of kings of the Sardinian kingdom. During the Savoyard Era, until 1848, the institutions of the Sardinian kingdom remained unchanged, but with the "Perfect Fusion" in that year, all the possessions of the House of Savoy House, comprising Savoy, Nice (now part of France), Piedmont and from 1815 Liguria, were merged into a unitary state. Although Sardinian by name, the kingdom had its parliament in Turin, where the Savoys resided, and its members were mainly aristocrats from Piedmont or the mainland.

In the late 18th century during the French Revolutionary Wars France tried to conquer Cagliari because of its strategic role in the Mediterranean sea (Expédition de Sardaigne). A French army landed on Poetto beach and advanced towards Cagliari, but the French were defeated by Sardinians who had decided to defend themselves against the revolutionary army. The people of Cagliari hoped to receive some concession from the Savoys in return for their defence of the town. For example, aristocrats from Cagliari asked for a Sardinian representative in the parliament of the kingdom. When the Savoyards refused any concession to the Sardinians, the inhabitants of Cagliari rose up against them and expelled all the representatives of the kingdom along with the Piedmontese rulers.[36] This insurgence is celebrated in Cagliari during Sa die de sa Sardigna ("The day of Sardinia") on the last weekend of April. However, the Savoys regained control of the town after a brief period of autonomous rule.

Modern age

The population by the 1840s had reached 29,000.[37] Starting in the 1870s, in the wake of the unification of Italy, the city experienced a century of rapid growth. Numerous buildings combined influences from Art Nouveau together with the traditional Sardinian taste for floral decoration; an example is the white marble City Hall near the port. Many buildings were erected by the end of the 19th century during the term of office of mayor Ottone Bacaredda. In 1905 he had to face up to the a violent, bloody revolt against the exorbitant cost of living, stoked by his political opponents and which caused a number of victims and extensive material damage. After various other ups and downs, and following another resignation, he was returned to office between 1911 and 1917. Ottone Bacaredda died in his modest house in Via San Giovanni, on 26 December 1921,[38]

During the Second World War Cagliari was heavily bombed by the Allies in February 1943. In order to escape from the danger of bombardments and difficult living conditions, many people were evacuated from the city into the countryside. In total the victims of the bombings were more than 2000[39] and about 80% of the buildings were damaged. The city received the Gold Medal of Military Valour.[39]

After the Italian armistice with the Allies in September 1943, the German Army took control of Cagliari and the island, but soon retreated peacefully in order to reinforce their positions in mainland Italy. The American Army then took control of Cagliari. Airports near the city (Elmas, Monserrato, Decimomannu, currently a NATO airbase) were used by Allied aircraft to fly to North Africa or mainland Italy and Sicily.

After the war, the population of Cagliari grew again and many apartment blocks and recreational areas were erected in new residential districts.

Coats of Arms of Cagliari

- 13th century

- From the 14th to 17th century

- From the 18th century to the present

Geography

And suddenly there is Cagliari: a naked town rising steep, steep, golden-looking, piled naked to the sky from the plain at the head of the formless hollow bay. It is strange and rather wonderful, not a bit like Italy. The city piles up lofty and almost miniature, and makes me think of Jerusalem: without trees, without cover, rising rather bare and proud, remote as if back in history, like a town in a monkish, illuminated missal. One wonders how it ever got there. And it seems like Spain—or Malta: not Italy. It is a steep and lonely city, treeless, as in some old illumination. Yet withal rather jewel-like: like a sudden rose-cut amber jewel naked at the depth of the vast indenture. The air is cold, blowing bleak and bitter, the sky is all curd. And that is Cagliari. It has that curious look, as if it could be seen, but not entered. It is like some vision, some memory, something that has passed away. Impossible that one can actually walk in that city: set foot there and eat and laugh there. Ah, no! Yet the ship drifts nearer, nearer, and we are looking for the actual harbour.

The city of Cagliari is situated in the south of Sardinia, overlooking the centre of the eponymous gulf, also called Golfo degli Angeli ("Bay of Angels") after an ancient legend. The city is spread over and around the hill of the historic district of Castello and nine other limestone hills of the middle-to-late Miocene, unique heights of a little more than 100 metres (330 ft) above sea level on the long plains of Campidano. The plain is actually a Graben formed during the Alpine orogeny of the Cenozoic, which separated Sardinia from the European continent, roughly where the Gulf of Lion is now. The Graben filled in the course of tectonic movements associated with the breakup of the ancient island Paleozoic skeleton.[41]

The repeated intrusion of the sea left calcareous sediments that formed a series of hills that mark the territory of Cagliari. Castello is where the fortified town arose in the Middle Age near the harbour of the port, other hills are those of Mount Urpinu, the St. Elias hill, also known as the Sella del Diavolo ("Saddle of the Devil") for its shape, Tuvumannu and Tuvixeddu, the site of the ancient Punic and Roman necropolis, the small Bonaria hill, where the basilica stands, and the San Michele hill, with the eponymous castle on top. The modern city occupies the flat spaces between the hills and the sea to the south and southeast, along the Poetto beach, the lagoons and ponds of Santa Gilla and Molentargius, and the remains of more recent marine intrusions, in an articulate landscape with many landmarks and panoramas of the bay, the plain, and the mountains that surround it on the east (The Seven Brothers and Serpeddì) and west (the mountains of Capoterra). On the cold, clear days of winter, the snowy peaks of Gennargentu can be seen from the highest points of the city.

The city has four historic neighbourhoods: Castello, Marina, Stampace and Villanova and several modern districts (such as San Benedetto, Monte Urpinu and Genneruxi at the east, Sant'Avendrace at the west, Is Mirrionis/San Michele at north and Bonaria, La Palma and Poetto at the south), grown when part of the ancient walls had been demolished in the middle of the 19th century.

Pirri

The comune of Cagliari has one circoscrizione, the town of Pirri (about 30.000 inhabitants), former village of the Campidano absorbed in the fast growth after the Second World War.

Parks and recreation

Cagliari is one of the "greenest" Italian cities. Every inhabitant of Cagliari has access to 87.5 square metres (942 sq ft) of public gardens and parks.[42]

Its mild climate allows the growth of numerous subtropical plants, such as Jacaranda mimosifolia, Ficus macrophylla, with some huge specimens in Via Roma and in the University Botanic Gardens, Erythrina afra with its stunning red flowers, Ficus retusa, which provides shade for several of the city's streets, Araucaria heterophylla, the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), the Canary Islands palm (Phoenix canariensis) and the Mexican Fan Palm (Washingtonia robusta).

Major city parks include:

- Monte Urpinu Park, the most wooded, is a low hill covered by a pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) and evergreen oak (Quercus ilex L.) forest with a dense Mediterranean maquis of mastic (Pistacia lentiscus L.), juniper (Juniperus phoenicea L.), Kermes oak (Quercus coccifera L.), wild olive (Olea europaea L. ssp. europaea, var. sylvestris) and tree spurge (Euphorbia dendroides L.). It extends for about 25 hectares (62 acres).

- Park of San Michele hill (about 25 hectares), with its medieval castle on the top;

- Terramaini Park, about 13 hectares (32 acres), with a little pond which is home to flamingos and other wading birds;

- Monte Claro Provincial Park, about 22 hectares (54 acres), which hosts the provincial library in an old mansion on the top of the hill;

- Ex-vetreria Pirri Park, about 2.5 hectares (6.2 acres);

- Public gardens, the oldest public esplanade of the city, planted in the 19th century, with a wonderful promenade of Jacaranda mimosifolia D.Don.

The Molentargius - Saline Regional Park[43] is located near the city. Some mountain parks, such as Monte Arcosu or Maidopis, with large forests and wildlife (Sardinian deer, wild boars, etc.) are also nearby.

The city is the starting and ending point of the Path of 100 Towers, which consist of a trekking route named after the 105 towers located along the whole Sardinian coast.[44]

Beaches

The main beach of Cagliari is the Poetto. It stretches for about 8 kilometres (5 mi), from Sella del Diavolo ("Devil's Saddle") up to the coastline of Quartu Sant'Elena. Poetto is also the name of the district located on the western stretch of the strip between the beach and Saline di Molentargius ("Molentargius's Salt Mine").

Another smaller beach is that of Calamosca near the Sant'Elia district. On the coast between Calamosca and Poetto beaches, among the cliffs of the Sella del Diavolo, lies Cala Fighera, a small bay.

Cagliari is close to other seaside locations such as Santa Margherita di Pula, Chia, Geremeas, Solanas, Villasimius and Costa Rei.

Climate

Cagliari has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa), with hot, dry summers and mild winters like other historical regions along the coast.[45] Its precipitation values also bring it closer to semi-arid conditions.[46][47] The summer extreme values can be slightly over 40 °C (104 °F), sometimes with very high humidity, while in winter, under special and rare conditions, the temperature drops slightly below zero. Heavy snowfalls occur on average every thirty years.[48]

The average temperature of the coldest month, January, is about 10 °C (50 °F), and of the warmest month, August, about 25 °C (77 °F). But heat waves can occur, due to African anticyclone, starting in June. From mid-June to mid-September, rain is a rare event, limited to brief afternoon storms. The rainy season starts in September, and the first cold days come in December.[48]

Winds are frequent, especially the mistral and sirocco; in summer a marine sirocco breeze (called s'imbattu in Sardinian language) lowers the temperature and brings some relief from the heat.[49][citation needed]

| Climate data for Cagliari (Elmas Airport), elevation: 4 m (13 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1981–-2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

44.6 (112.3) |

41.8 (107.2) |

35.9 (96.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

44.6 (112.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.1 (89.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

22.5 (72.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

17.3 (63.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37.1 (1.46) |

33.9 (1.33) |

32.1 (1.26) |

45.6 (1.80) |

26.2 (1.03) |

12.5 (0.49) |

3.10 (0.12) |

11.4 (0.45) |

38.5 (1.52) |

43.9 (1.73) |

74.0 (2.91) |

54.9 (2.16) |

413.2 (16.26) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.5 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.4 | 4.2 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 58.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.7 | 73.4 | 71.4 | 69.8 | 67.8 | 63.5 | 61.3 | 62.7 | 66.7 | 71.6 | 76.3 | 77.9 | 70.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 155.0 | 166.0 | 217.6 | 222.6 | 271.3 | 312.3 | 339.8 | 314.0 | 240.3 | 199.3 | 150.3 | 140.7 | 2,729.2 |

| Source 1: NCEI.NOAA[50] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat,[51] Servizio Meteorologico[46] and WeatherBase[52] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1485 | 5,088 | — |

| 1603 | 7,868 | +54.6% |

| 1678 | 13,428 | +70.7% |

| 1688 | 17,390 | +29.5% |

| 1698 | 15,677 | −9.9% |

| 1728 | 18,365 | +17.1% |

| 1751 | 20,948 | +14.1% |

| 1771 | 24,254 | +15.8% |

| 1776 | 27,102 | +11.7% |

| 1781 | 25,905 | −4.4% |

| 1821 | 31,935 | +23.3% |

| 1824 | 30,685 | −3.9% |

| 1838 | 31,157 | +1.5% |

| 1844 | 33,700 | +8.2% |

| 1848 | 33,826 | +0.4% |

| 1857 | 35,369 | +4.6% |

| 1861 | 37,243 | +5.3% |

| 1871 | 37,135 | −0.3% |

| 1881 | 43,472 | +17.1% |

| 1901 | 61,678 | +41.9% |

| 1911 | 70,132 | +13.7% |

| 1921 | 73,024 | +4.1% |

| 1931 | 83,359 | +14.2% |

| 1936 | 88,122 | +5.7% |

| 1951 | 117,292 | +33.1% |

| 1961 | 155,931 | +32.9% |

| 1971 | 189,957 | +21.8% |

| 1981 | 197,517 | +4.0% |

| 1991 | 183,659 | −7.0% |

| 2001 | 164,249 | −10.6% |

| 2011 | 149,883 | −8.7% |

| 2021 | 149,092 | −0.5% |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 100,620 | — |

| 1936 | 106,649 | +6.0% |

| 1951 | 138,539 | +29.9% |

| 1961 | 183,784 | +32.7% |

| 1971 | 223,376 | +21.5% |

| 1981 | 233,848 | +4.7% |

| 1991 | 204,237 | −12.7% |

According to ISTAT,[53] in 2014 there were 154,356 people residing in Cagliari (+3.0% compared with 2011), of whom 71,522 were male and 82,834 female for a sex ratio of 0.86. Minors (children aged 18 and younger) totaled 12.92% of the population, compared to pensioners at 24.81%. The average age of Cagliari residents is 47.44. The ratio of the population over 65 years of age to that under the age of 18, is 53.39%. The elderly population, defined as being over 65 years of age, has increased by 21.95% over the last 10 years. The current birth rate in Cagliari is 6.29 births per 1,000 inhabitants. The average number of people of any age per household is 2.11 and the percentage of households composed of a single person is 42.53%. The population of Cagliari is structured like that of other first world countries, especially as to the prevalence of an elderly population. The trend of these rates in the Cagliari metropolitan area is proportionally reversed in the suburbs, where most younger families move.

As of 2020, 5.8% (8,796 people) of the population was foreign, of which the largest group were Filipinos (17.21%), followed by Ukrainians (10.38%), Romanians (8.42%), Senegalese (8.25%) and Chinese (7.94%).[54]

In 1928, during the fascist regime, the neighbouring municipalities of Pirri, Monserrato, Selargius, Quartucciu and Elmas, were merged with that of Cagliari. Mussolini's regime wanted to streamline the local administration by eliminating many small towns and at the same time show that Italy was a major power with many large cities. After the war these small municipalities gradually regained their autonomy, except for the former town of Pirri.

The first table shows the inhabitants of the town in its present borders, the second one the commune population including the merged municipalities.

Metropolitan City

The Metropolitan City of Cagliari has been established in 2016 by a Sardinia Regional Law and totals about 420,000 inhabitants according to ISTAT. It is composed of 17 municipalities along the coast of the gulf and up to 20 kilometres (12 mi) of the inner Campidano plain.

It covers an area on the plain of Campidano between large basins (Santa Gilla lagoon and salt mills of about 30 km2 or 3200 acres), ponds (Molentargius), 16,22 km2 (40,10 acres) and the depopulated mountains up to 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) above sea level. The mountains are largely covered by forests mostly managed by the Ente Foreste of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia. To the west these amount to 256 square kilometres (99 sq mi) on the Capoterra and Pula mountains. Monte Arcosu WWF Natural Reserve has another 36 square kilometres (14 sq mi), and to the east on Mount Serpeddì and Sette Fratelli there are a total of 132 square kilometres (51 sq mi) of forest.

The Metropolitan City is defined by municipalities where the population increased between the last two censuses, in a region where the population is otherwise generally decreasing. These municipalities welcome immigrants to the urban area whose main nucleus, the city of Cagliari, has a high number of elderly people.

In the last century, the population of the municipalities of the metropolitan area increased by 354% and in the last 50 years by 158% (1911: 128,444; 1961: 288,683; 2011: 454,819). For the whole of Sardinia this increase was respectively 88% and 15% (1911: 868,181; 1961: 1,419,362; 2011: 1,639,362). The urbanisation towards the area of Cagliari was, in percentage terms, impressive, making the capital of the island a metropolis surrounded by rural areas increasingly depopulated. This urbanisation is also reflected in the concentration in Cagliari of most of the economic activities and wealth.

Economy

According to 2014 data from the Italian Ministry of Economic Affairs,[55] the inhabitants of Cagliari benefited a per capita income of 23,220 euros (being the fifth Regional Capital), that is the 122% of the national average, while all of Sardinia benefited only 16,640 euros, being the 13th Region and 86% of the national average. The metropolitan area benefited an average income of 19,185 euros, 103% of the national average. With the 26% of the island population the Cagliari Metropolitan City produces the 31% of its GDP.

As the capital city of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia, Cagliari is the administrative hub and headquarters of the region as well as of the provincial and regional offices of the Italian central administration. Cagliari is also the main trade and industrial centre of the island, with numerous commercial sites and factories within its metropolitan boundaries.

Cagliari is the fourth port of Italy for movement of goods in tons (35,922,468), and the 18th for passengers (705,715), of whom 394,697 cruise passengers (8th in Italy).[56]

The first department store, (La Rinascente) opened in 1931 in the centre of the city, and it is still open today. Nowadays there are many commercial centres in the metropolitan area (Le Vele, Santa Gilla, La Corte del Sole, Marconi) hosting many European chain stores such as Auchan, Metro AG, Lidl, MediaWorld, Euronics, Jysk, IKEA,[57] Carrefour and Bata Shoes. Cagliari is also home to an Amazon customer service center.[58]

Cagliari is the main operational headquarters of the Banco di Sardegna, which belongs to the BPER Group and is listed on Borsa Italiana, of the Banca di Cagliari. Banca di Credito Sardo was based in Cagliari until it was absorbed by the parent company Intesa Sanpaolo.

The Macchiareddu-Grogastru area between Cagliari and Capoterra is one of the most important industrial areas of Sardinia, in conjunction with a large international container terminal port at Giorgino.[59] Beside having one of the biggest container terminals on the Mediterranean Sea, Cagliari also has one of the largest fish markets in Italy offering for sale a vast array of fish to both the public and traders. The communications provider Tiscali also has its headquarters in Cagliari.

Multinational corporations like Coca-Cola, Heineken, Unilever, Bridgestone and Eni Group have factories in town. One of the six oil refinery supersites in Europe, Saras, is located within the metropolitan area at Sarroch.

Tourism is one of the major industries of the city, although historical venues such as its monumental Middle Ages and Early modern period defence system, its Carthaginian, Roman and Byzantine ruins are less highlighted compared to the recreational beaches and coastline. Cruise ships touring the Mediterranean often stop for passengers at Cagliari, and the city is a traffic hub to the nearby beaches of Villasimius, Chia, Pula and Costa Rei, as well as to the urban beach of Poettu. Pula is home to the archaeological site of the Punic and Roman city of Nora. Especially in summer many clubs and pubs are goals for young locals and tourists. Pubs and night-clubs are concentrated in the Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, a narrow street in Stampace district, in the Marina district, near the port and in the Castello district, The clubs are mostly to be found on the Poetto Beach (in summer) or in Viale Marconi (in winter). In Cagliari there are 180 B&B and 22 hotels that totals 3,300 beds. There are many others hotels in seaside resort of his gulf.

Main sights

Considerable remains of the ancient city of Karalis are still visible, including those of the Tuvixeddu necropolis (the largest Punic necropolis still in existence), the Roman amphitheatre, traditionally called Is centu scalas ("One hundred steps"), and of an aqueduct used to provide generally scarce water. Still visible are also some ancient cisterns of vast extent, the ruins of a small circular temple, and numerous sepulchres on a hill outside the modern town that appear to have formed the necropolis of the ancient city.[60]

The Palaeo-Christian Basilica of San Saturnino, dedicated to a martyr killed under Diocletian's reign, Saturninus of Cagliari, patron saint of the city, was built in the 5th century. Of the original building the dome and the central part remain, to which two arms (one with a nave and two aisles) were added later. A Palaeo-Christian crypt is also under the church of San Lucifero (1660), dedicated to Saint Lucifer, a bishop of the city. The church has a Baroque façade with ancient columns and sculpted parts, some of which came from the nearby necropolis.

The old medieval town (called Castello in Italian, Casteddu de susu in Sardinian, "the upper castle") lies on top of a hill with a view of the Gulf of Cagliari (also known as Angels' Gulf). Most of its city walls are intact and include two early 14th-century white limestone towers, the Torre di San Pancrazio and the Torre dell'Elefante, typical examples of Pisan military architecture. The local white limestone was also used to build the walls of the city and many other buildings, besides the towers. The exact period of construction of a fortress on this hill is unknown at present, due to the superposition of layers of buildings along the history. Some scholars[61] have suggested a first urbanization of the quarter in the Punic era on the basis of similarity of the planimetry with the contemporary Carthaginian fortress of Monte Sirai. Recently, archaeological excavations have identified Punic and Roman buildings under the ramparts of the fortress.[62] Already the Roman poet Varro called the city "Vicus munitus", a fortified city, and sixteenth-century authors describe a Roman acropolis perhaps still visible in their day.[63][64]

D. H. Lawrence, in his memoir of a voyage to Sardinia, Sea and Sardinia, that he undertook in January 1921, described the effect of warm Mediterranean sunlight on the white limestone city and compared Cagliari to a "white Jerusalem".

The cathedral was restored in the 1930s, returning the former Baroque façade into a Medieval Pisan-style façade more akin to the original appearance of the church in the 13th century. The bell tower is original. The interior has a nave and two aisles, with a pulpit (1159–1162) sculpted for the Cathedral of Pisa but later donated to Cagliari. The crypt houses the remains of martyrs found in the Basilica of San Saturno (see below). Near the cathedral is the palace of the provincial government. Before 1900 it was the island's governor's palace.

The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Bonaria (from which the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina, gets its name) was built by the Catalans in 1324–1329 when they were besieging the Pisans in Castello. It has a small Gothic portal in the façade and the interior houses a wooden statue of the Madonna, which, after having been thrown off a Spanish ship, landed at the foot of Bonaria hill. Bonaria hill is also the location of the Monumental Cemetery of Bonaria.

The Chiesa della Purissima is a Catalan Gothic church built in the 16th century in the Castello distinct.

The other early districts of the town (Marina, Stampace and Villanova) retain much of their original character. In Stampace the Torre dello Sperone, another tower built by the Pisans in the late 13th century, is located, as well as two important monumental churches: the Collegiata di Sant'Anna and the Chiesa di San Michele, both built in the 18th century in a baroque style. Many more churches, both old and modern, can be found throughout the city.

The Promenade Deck and the Terrazza Umberto I were designed in 1896 by the engineers Joseph Costa and Fulgenzio Setti. The entire building was built of white and yellow limestone in a classical style with Corinthian columns. It was opened in 1901. A staircase with two flights provides access from Constitution Square. It is interrupted by a covered walkway and ends beneath the Arc de Triomphe, in the Terrazza Umberto I. In 1943, during World War II, the staircase and the Arch of Triumph were severely damaged by aerial bombardment, but after the conflict they were faithfully reconstructed.

From the Terrazza Umberto I the Bastion of Santa Caterina can be accessed via a short flight of steps. Here there was once an old Dominican convent, destroyed by fire in 1800. According to tradition, the conspiracy to kill the Viceroy Camarassa in 1666 was set up in the surroundings of the monastery.

The Promenade Deck was inaugurated in 1902. At first it was used as a banqueting hall, then during the First World War as an infirmary. In the 1930s, during the period of sanctions, it was an exhibition of autarky [citation needed] During World War II it served as a shelter for displaced people whose homes had been destroyed by bombs. In 1948 it hosted the first Trade Fair of Sardinia. After many years of decay, the Promenade was restored and re-evaluated as a cultural space reserved especially for art exhibitions.[65]

The modern districts built in the late 19th and early 20th century contain examples of Art Deco architecture, as well as controversial examples of Fascist neoclassicism architecture, such as the Court of Justice (Palazzo di Giustizia) in Republic Square. The Court of Justice is near the biggest city park, Monte Urpinu, with its pine trees, artificial lakes, and a vast area with a hill. The Orto Botanico dell'Università di Cagliari, the city's botanical garden, is also of interest.

Culture

The city has numerous libraries and is also home to the State Archive, containing thousands of handwritten documents from the foundation of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1325 AD) to the present. In addition to numerous local and university department libraries, the most important libraries are the old University Library,[66] with thousands of ancient books, the Provincial Library,[67] the Regional Library,[68] and the Mediateca of the Mediterranean,[69] which contains the municipal archive and library collection.

In the first century B.C. a famous singer and musician from Cagliari, Tigellius, lived in Rome and was satirized by Cicero and Horace. The history of Sardinian literature begins in Cagliari in the first century A.D. In the funerary monument of Atilia Pomptilla, carved into the rock of the necropolis of Tuvixeddu, poems are engraved in Greek and Latin dedicated to his dead wife. Some of them, particularly those in the Greek language, have literary merit.

The first Sardinian literary author known was Bishop Lucifer of Cagliari, who wrote severe pamphlets against the Arian heresy in the fourth century A.D. Only in the eleventh century A.D. did the first texts of an administrative nature appear in the modern Sardinian language, together with hagiographies of local martyrs written in Latin.

Life in Cagliari has been depicted by many writers, starting with the late Roman poet Claudian. In the late 16th century, the local humanist Roderigo Hunno Baeza dedicated to his town a didactic Latin poem, Caralis Panegyricus.[70] At the beginning of the 17th century Juan Francisco Carmona wrote a hymn to Cagliari in Spanish; Jacinto Arnal De Bolea published in 1636, in Spanish, the first novel set in Cagliari, entitled El Forastero.[71] David Herbert Lawrence wrote about the city in his Sea and Sardinia.

Modern writers connected to Cagliari include Giuseppe Dessì, Giulio Angioni, Giorgio Todde, Sergio Atzeni, (who set many of his novels and short stories, such as Bakunin's Son, in ancient and modern Cagliari), Flavio Soriga.

Cagliari was the birthplace or residence of the composer Ennio Porrino, of the film, theatre and TV director Nanni Loy, and of the actors Gianni Agus, Amedeo Nazzari and Pier Angeli (born Anna Maria Pierangeli).

Excluding the Roman era amphitheater, the first theater was inaugurated in Cagliari in 1767: the Teatro Zapata, later becoming the Civic Theatre. Devastated by bombing in 1943, it was recently restored, but the roof was not rebuilt, and today it serves as an open-air theatre. The Politeama Regina Margherita, inaugurated in 1859, was destroyed by fire in 1942 and never rebuilt.

Although opera had, and in part still has, a solid tradition the city, it was left without a true theater until 1993 when a new opera house, the Teatro Lirico, was inaugurated.[72] Inside there is a music compound with a music conservatory with its own auditorium, and a music park. Cagliari is and was home to opera singers such as the tenors Giovanni Matteo Mario (Giovanni Matteo De Candia, 1810–1883) and Piero Schiavazzi (1875–1949), the baritone Angelo Romero (born 1940), the contralto Bernadette Manca di Nissa, born 1954 and the soprano Giusy Devinu (1960–2007).

The Italian pop singer Marco Carta was also born in Cagliari, in 1985.

The old Teatro Massimo was only recently renovated and is now the seat of the Teatro Stabile of Sardinia.[73] The Municipal Auditorium, in the former 17th-century church of Santa Teresa, is the seat of the Scuola di Arte Drammatica (School of Dramatic Art) di Cagliari,[74] while the Teatro delle Saline ("Saltworks Theatre"),[75] is home of Akroama, Teatro Stabile di Innovazione ("Permanent Theater of Innovation").[76]

Finally, some comic and satirical theater companies are active in the city, the most well known being the "Compagnia Teatrale Lapola",[77] which offers an urban version of the traditional campidanese comic theater.[78]

Founded by Bepi Vigna, Antonio Serra and Michele Medda, a comic book school, the Centro Internazionale del Fumetto ("Comic Strip International Centre")[79] has been active for several decades. Its founders invented and designed the comic characters Nathan Never and Legs Weaver.

Museums and galleries

The Polo museale di Cagliari "Cittadella dei musei" (Citadel of Museums) is home to:

- Museo archeologico nazionale di Cagliari (National Archeological Museum of Cagliari), the most important archeological museum of Sardinia, which contains finds from the Neolithic period (6000 B.C.) to the Early Middle Ages about 1000 A.D.[80]

- Museo civico d'arte siamese Stefano Cardu (Civic Siamese Art Museum "Stefano Cardu") the most important European collection of Siamese art, gathered by a Cagliaritan collector at the beginning of the 20th century.[81]

- Museo delle cere anatomiche Clemente Susini (Anatomical Waxwork Museum "Clemente Susini").[82] This collection of anatomical waxworks is considered one of the finest in the world, and perfectly describes the human body, testifying to the state of medical and surgical knowledge at the beginning of the 19th century. The collection was created by the sculptor Clemente Susini and includes faithful reproductions of dissections of cadavers performed in the School of Anatomy in Florence 1803-1805 A.D.

- Pinacoteca nazionale (National Picture Gallery)[83]

- Galleria comunale d'arte (Civic art Gallery) with an important exposition of modern Italian painting offered to the city by its collector (Ingrao Collection), and an exposition of Sardinian artists.[84]

- Collezione sarda Luigi Piloni (University Sardinian Collection "Luigi Piloni")[85]

- ExMà, MEM, Castello di San Michele, and Il Ghetto exposition centers[86]

- Museo di Bonaria (Basilical Church Museum of Bonaria),[87] with an interesting ex-voto collection

- Museo del Duomo (Cathedral Museum);[88]

- Museo del tesoro di Sant'Eulalia (Treasure Museum of Saint Eulalia of Barcelona;[89] with its important Roman era underground area.

- Orto botanico di Cagliari (University Botanical Gardens)[90]

Feast of Sant'Efis

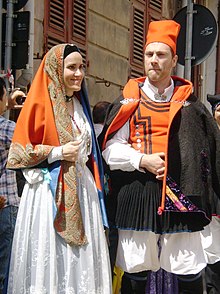

The Feast of St. Ephysius (Sant'Efisio in Italian, Sant'Efis in Sardinian) is the most important religious event of Cagliari, taking place every year on 1 May. During this festival, thousands of people from folk groups all over Sardinia wear their traditional costumes. The saint is escorted by the traditional ancient Milicia, the deputy mayor (Alter Nos), numerous confraternities, and a convoy of chariots pulled by oxen in a procession to Nora (near modern Pula), 35 km (22 mi) from Cagliari, where, according to tradition, he was beheaded. In addition to being one of the oldest, it is also the longest Italian religious procession, with about 70 km (43 mi) of walks over four days, and the largest in the Mediterranean area.

A plague was spreading throughout Sardinia, starting in 1652, and the epidemic infected Cagliari in particular, killing some ten thousand inhabitants. According to legend, in 1656 St. Ephysius appeared to the Spanish Viceroy, Francisco Fernández de Castro Andrade, Count of Lemos to request a procession on 1 May, in order to free the city from the plague. The Municipality of Cagliari swore that, if the plague disappeared, a procession would be held every day in the saint's honor, starting from the Stampace district and ending at Nora where the saint was martyred. In September the plague ended, and the procession and festival was therefore regularly held starting the following year on 1 May. The procession was held even during the last war; a statue of the saint was placed on a lorry and, through city ruins of the devastated by the bombs, arrived safely in Nora.

Other events

Other feasts and events in Cagliari include:

- The Carnival

- Holy Week and Easter celebrations

- Sea processions of St. Francis of Paola, held in May, and Nostra Signora di Bonaria, in July

- Cagliari Fair, in early May

- Audi MedCup regatta

Languages

The native language of Cagliari, declared official along with Italian,[91] is Sardinian (sardu), a Romance language, specifically the Campidanese dialect (campidanesu) in its local variant (casteddaju).

The variant of Cagliari in its high register has traditionally represented the linguistic model of reference for the entire southern area of the island, and the high social variant used by the middle class in the whole Campidanese domain, as well as the literary model of reference for writers and poets. This language is less spoken by the younger generations in the city, who use Italian instead as that language is compulsory in education and the mass media. Italian has increasingly become predominant in social relations, both formal and informal, relegating Sardinian to a mostly marginal role in everyday life. Young people often have only passive competence in the language, gathered from elderly relatives who still speak it, as their parents often speak only Italian, or they may use a slang (italianu porceddinu) that mixes both Sardinian and Italian.

Since Cagliari was the metropolis of the ancient Roman province, it absorbed innovations coming from Rome, Carthage, and Constantinople, and its language probably reflected late Latin urban dialects of the 5th-century core cities of the empire.

Gastronomy

Cagliari has some unique gastronomic traditions: unlike the rest of the island its cuisine is mostly based on the wide variety of locally available seafood. Although it is possible to trace influences from Catalan, Sicilian and Genoese cuisine, Cagliaritan food has a distinctive and unique character.

Excellent wines are also part of Cagliaritanians' dinners, like the Cannonau, Nuragus, Nasco, Monica, Moscau, Girò and Malvasia, produced in the nearby vineyards of the Campidano plain.

Media

The main newspaper of Sardinia is L'Unione Sarda, it was founded in Cagliari in 1889. It was one of the first European newspapers to have its own website in 1994. It has a circulation of about 85,000 copies.

The main regional headquarters of RAI, the Italian state-owned radio and television network, is in Cagliari. There are also two regional television and radio companies as well as numerous information sites on the internet.

Sports

Cagliari is home to the football team Cagliari Calcio, winner of the Italian league championship in 1970, when the team was led by Gigi Riva. Founded in 1920, the club played at the Stadio Sant'Elia in the city from 1970 until it was closed in the summer of 2017, causing the club to temporarily relocate to the provisional Sardegna Arena (now Unipol Domus). Sant'Elia was the venue for three 1990 FIFA World Cup matches.[92]

Cagliari is an ideal location for water sports such as surfing, kitesurfing, windsurfing and sailing due to strong and reliable favourable winds. Field hockey is also popular, with two teams in the Italian top division, G.S. Amsicora and C.U.S. Cagliari, the first of which won the league title more often than any other Italian team in the men's championship (20) and is also the protagonist in the women's division.

Sport venues in Cagliari include:

- Unipol Domus

- Tennis Club Cagliari[93]

- Rockfeller sports hall

- Rockfeller skating rink

- Via dello Sport gymnastics hall

- Terra Maini Olympionic pool

- Amsicora Stadium[94]

- Rari Nantes pool[95][96]

- Esperia pool

- Riccardo Santoru athletics stadium

- Civic pool

- Acquasport pool

- Poettu hippodrome[97]

- Mario Siddi fencing gymnasium

- Mulinu Becciu tennis table hall

- Facilities of the University Sports Center, C.U.S. Cagliari[98]

Government

Cagliari is the hub of the administration offices of the Sardinia Autonomous Region and of Cagliari Province. It is also the home of several local offices of the Italian central administration.

It is the seat of the Superintendency of Cultural and Environmental Heritage,[99] of the Sardinia Archival Superintendency[100] and of the Archeological Superintendency[101] of the Cultural Heritage Ministry,[102] of the Sardinia and Provincial seat of the Employment and Social Policies Ministry, of the regional offices of the Finance and Economy Ministry,[103] and of some branch offices of the Health Ministry.

Cagliari is home to all criminal, civil, administrative and accounting courts for Sardinia of the Ministry of Justice up to the High Court of Assizes of Appeal. It was home to a prison, Buon Cammino, built in the late 19th century, famous because no one has ever managed to escape. A new modern prison has been built in the nearby town of Uta.

Traditionally, votes in Cagliari are oriented towards the center-right wing. Since World War II, all the mayors belonged to the Christian Democracy party with the exception of Salvatore Ferrara, from the Socialist Party, allied with the former. After the collapse of the traditional parties in the 1990s, the mayors belonged to the party or the coalition led by Silvio Berlusconi. The current economic and political crisis that affects Italy has prompted the electorate toward a large abstention and to elect a young mayor, Massimo Zedda, who belongs to a centre-left alliance. In the last municipal elections in June 2016, Massimo Zedda was confirmed in the first round with 50.86% of the votes.

Education

Cagliari is home to the University of Cagliari,[12] the largest public university in Sardinia, founded in 1626. It currently includes six faculties: Engineering and Architecture, Medicine and Surgery, Economics, Juridical and Political Sciences, Basic Sciences, Biology and Pharmacy, Humanistic Studies.

It is attended by about 35,000 students.[104] All science faculties of the university, as well as the university hospital, have been transferred to a new "University Citadel", located in Monserrato. Cagliari's downtown houses the engineering and the humanities divisions and, in the Castle, the seat of the Rector, in an 18th-century palace with a library of thousands of ancient books.

Cagliari is also the seat of the Pontifical Faculty of Theology of Sardinia and of the European Institute of Design.

Health care

Life expectancy in Cagliari is high: 79.5 years for men and 85.4 for women (provincial level).

There has been a public hospital in Cagliari since the 17th century. The first modern structure was built in the middle of the 19th century, designed by the architect Gaetano Cima. This hospital is still operating, although all its departments will eventually be transferred to the new University Hospital[105] in Monserrato.

Among the other public hospitals, the Giuseppe Brotzu (San Michele) Hospital[106] was recognized in 1993 as a High Specialization Nationally Relevant Hospital, particularly for liver, heart, pancreas and bone marrow transplants.

Other public hospitals in the city include: the Santissima Trinità or commonly Is Mirrionis; the Binaghi, specialised in pulmonology; Marino specialised in traumatology, hyperbaric medicine and spinal cord injuries; Businco specialised in oncology; and Microcitemico, specialised in thalassemia, Genetic diseases and rare diseases. There are in addition many private hospitals.

Despite its dry climate, thanks to the regional system of dams, every inhabitant of Cagliari may have 363 litres (96 US gal) per day of safe drinking water.

Waste sorting is still at a low level: only 33.4 percent of waste is separated.

Transport

Airport

The city is served by the Cagliari-Elmas International Airport,[107] located a few kilometres from the centre of Cagliari. It is the 13th busiest aeroport in Italy by passengers traffic with around 4,370,000 passengers in 2018. A railway line connects the city to the airport; walkways join the railway station to the air terminal. The terminal is also connected to the city by highway SS 130 and by a bus service run by the ARST company[108] to the central bus station in Matteotti square, in the centre of the city.

There are other airports not too far from the city: Deciomannu Airport, a NATO military airport and three fields for air sports, Serdiana (used in particular for skydiving[109]), Castiadas and Decimoputzu.

Roads

The following national roads begin in Cagliari:

Carlo Felice to Sassari - Porto Torres (motorway-like until Oristano) and to Olbia (SS131 Central Nuorese Branch).

Carlo Felice to Sassari - Porto Torres (motorway-like until Oristano) and to Olbia (SS131 Central Nuorese Branch). Iglesiente, to Iglesias and Carbonia.

Iglesiente, to Iglesias and Carbonia. Orientale Sarda, which connects Cagliari to Tortolì and Olbia, ending in Palau, across from Corsica.

Orientale Sarda, which connects Cagliari to Tortolì and Olbia, ending in Palau, across from Corsica. Sulcitana, connecting Cagliari with Sulcis along the coast.

Sulcitana, connecting Cagliari with Sulcis along the coast. Cagliaritana

Cagliaritana del Gerrei, to Ballao and Ogliastra.

del Gerrei, to Ballao and Ogliastra.- Provincial Road 17 connects Poetto Villasimius.

Ports

The port of Cagliari is divided in two sector, the old port and the new international container terminal. The port system of Cagliari-Sarroch is the third for freight traffic in Italy with a movement of about 38 million tons in 2017.[110] Cagliari has scheduled services by passenger ship to Civitavecchia, Naples and Palermo. In Cagliari there are also two other small touristic ports, Su Siccu (Lega Navale) and Marina Piccola.

Railways

The Ferrovie dello Stato railway station in Cagliari has services to Iglesias, Carbonia, Olbia, Golfo Aranci, Sassari and Porto Torres.[111]

The nearby commune of Monserrato is the terminal railway station of a narrow gauge line to Arbatax and Sorgono.

Urban and suburban mobility

Bus and trolleybus services, managed by CTM[112] (more than 30 lines) and ARST,[113] connect internal destinations in the city and in the metropolitan area; Cagliari is one of the few Italian cities with an extensive trolleybus network, whose fleet was fully renewed with new vehicles in 2012–2016. A light rail service, MetroCagliari, operates between Piazza Repubblica and the new university campus near Monserrato (line 1) and from Monserrato San Gottardo and Settimo San Pietro (line 2). A line between Piazza Repubblica and Piazza Matteotti, the city transport hub (with train, urban and extra-urban bus stations), is planned. Trenitalia, the primary train operator in Italy, operates a metro train service between Cagliari Central Station and Decimomannu, which connects the airport with the city center. A public bike-sharing service is operating with pick-up points at Via Sonnino - Palazzo Civico, Piazza Repubblica, Piazza Giovanni 23, and Marina Piccola.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Cagliari is twinned with:

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires, Argentina Nanyuki, Kenya

Nanyuki, Kenya Pisa, Italy

Pisa, Italy Vercelli, Italy

Vercelli, Italy Turin, Italy

Turin, Italy Padua, Italy, since 2002

Padua, Italy, since 2002 Biella, Italy, since 2003

Biella, Italy, since 2003

Consulates

In Cagliari there are at present (2018) the following consulates:[114]

See also

Notes

- ^ Long name (defunct): Casteddu de Càlaris, "Castle of Caralis".

References

Citations

- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Population data from Istat

- ^ "Cagliari" (US) and "Cagliari". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ^ "Cagliari". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Cagliari". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Aarhus". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Regione Autonoma della Sardegna". Regione.sardegna.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Statistiche Istat". Dati.istat.it. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Data services - Eurostat".

- ^ "Cagliari art (Italian Language Schools and Courses to Learn Italian in Italy.)". It-schools.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ "Nell'Italia delle tasse Milano stacca tutti - Guarda il reddito del tuo Comune". Il Sole 24 ORE. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ a b sistemi e grafiche netsoul srl www.netsoul.net. "Universitр degli studi di Cagliari". unica.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Chiesa di Cagliari". Chiesadicagliari.it. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Cagliari". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ Mastino (2006).

- ^ Claudian, De Bello Gildonico, IV A.D.: city located in front of Libya (Africa), founded by the powerful Tyro, Karalis extends in length, between the waves, with a small bumpy hill, disperses headwinds. It follows a port in the mid of the sea, and all strong winds are softened in the shelter of the pond. (521. Urbs Lybiam contra Tyrio fundata potenti 521. Tenditur in longum Caralis, tenuemque per undas 522. Obvia dimittit fracturum flamina collem. 523. Efficitur portus medium mare: tutaque ventis 524. Omnibus, ingenti mansuescunt stagna recessu)

- ^ M.L.Wagner,La lingua sarda, storia spirito e forma

- ^ Livy xxiii. 40, 41.

- ^ Id. xxx. 39.

- ^ Attilio Mastino (a cura di), Storia della Sardegna antica, Il Maestrale, Nuoro,2005

- ^ ii. 6. § 35.

- ^ xli. 6, 12, 17.

- ^ Julius Caesar Commentarii de Bello Civili i. 30.

- ^ Hirt. B. Afr. 98.

- ^ Cassius Dio xlviii. 30.

- ^ Pliny iii. 7. s. 13; Strabo v. p. 224; Pomponius Mela, ii. 7; Antonine Itinerary pp. 80, 81, 82, etc.

- ^ Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, 3.15 and 5.12

- ^ Claud. B. Gild. 520-24.

- ^ Pliny l. c.; Ptolemy iii. 3. § 8.

- ^ Corrado Zedda, 2017, Il Giudicato di Cagliari: storia, società, evoluzione e crisi di un regno sardo

- ^ Raimondo Pinna, 2010, Santa Igia. La Città del Giudice Guglielmo, edizioni Condaghes

- ^ a b c Casula 1994, p. 209-210.

- ^ Casula 1994, p. 210-212.

- ^ Casula 1994, p. 304.

- ^ "Guide to Cagliari, Villasimius, Costa Rei" (PDF). CharmingSardinia. February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2009.

- ^ Casula 1994, p. 468.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.IV, (1848), London, Charles Knight, p.12

- ^ "Bacaredda Ottone - Cimitero Monumentale di Bonaria - Cagliari" [Bacaredda Ottone - Monumental Cemetery of Bonaria - Cagliari]. Cimitero Monumentale Bonaria. 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Comune Cagliari News, Bombe su Cagliari: cronologia di una strage".

- ^ http://www.online-literature.com/dh_lawrence/sea-and-sardinia/2/ Ch. 2 and 3

- ^ R. Pracchi; A. Terrosu Asole, eds. (1971). Atlante della Sardegna. Cagliari: Editrice la Zattera.

- ^ "Urbes" (PDF). www.istat.it. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Parco Molentargius - Saline". Parcomolentargius.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Carrizzo, Rosanna (16 October 2017). "The 100 towers way, the path to fall in love with Sardinia". The Wom Travel (in Italian). Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Cagliari, Italy Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Climatologia - Ricerca Dati". Servizio Meteorologico dell'Aeronautica Militare. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ Wickens, Gerald E. (1998), "Arid and Semi-arid Environments of the World", in Wickens, Gerald E. (ed.), Ecophysiology of Economic Plants in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands, Adaptations of Desert Organisms, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 5–15, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-03700-3_2, ISBN 9783662037003

- ^ a b "Climate and Average Weather Year Round in Cagliari". Weather Spark. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Furberg, M.; Steyn, D. G.; Baldi, M. (30 June 2002). "The climatology of sea breezes on Sardinia". International Journal of Climatology. 22 (8): 917–932. Bibcode:2002IJCli..22..917F. doi:10.1002/joc.780. ISSN 0899-8418. S2CID 129846554.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020: CagliariElmas-16560" (CSV). ncei.noaa.gov (Excel). National Oceanic and Atmosoheric Administration. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ "moyennes 1981/2010".

- ^ "Cagliari, Italy Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Cittadini stranieri Cagliari 2020". Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "La classifica dei redditi dei comuni italiani - Twig". Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "AUTORITA' DI SISTEMA PORTUALE - MOVIMENTI PORTUALI" (PDF). 2008.

- ^ "Punto IKEA ordina, arreda di Cagliari orari, aperture". Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "Cagliari, Italy". Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ http://www.cict.it Archived 1 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smyth's Sardinia, pp. 206, 215Valery, Voyage en Sardaigne, c. 57.

- ^ Ferrucio Barreca, La Sardegna fenicia e punica, Storia della Sardegna antica e moderna, edizioni Chiarella, 1984

- ^ "Cagliari - indagini archeologiche presso il bastione di Santa Caterina" (PDF). Fasti Online. ISSN 1828-3179.

- ^ Juan Francisco Carmona, Hymno a Càller

- ^ Roderigo Hunno Baeza, Caralis panegyricus

- ^ Dozzo, Alessia (7 September 2020). "Bastion of Saint Remy, history of one of Cagliari's symbols". Cagliarimag.com. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "Biblioteche - Direzione regionale beni culturali e paesaggistici della Sardegna". www.sardegna.beniculturali.it. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Provincia di Cagliari | Biblioteca Provinciale Ragazzi". Provincia.cagliari.it. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Sardegna Biblioteche - Attività - Biblioteca regionale". Sardegnabiblioteche.it. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Comune di Cagliari| MEM - Mediateca del Mediterraneo: Biblioteca Comunale Generale e di Studi Sardi - Archivio Storico - Mediateca". Comune.cagliari.it. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Miscellaneous codex preserved in the Civic Library of Cagliari, edited by Francesco Alziator, 1954

- ^ Jacinto Arnal de Bolea, El Forastero, Emprenta A. Galgerin, Càller, 1636, republished by the editor Marìa Dolores, Garcìa Sànchez, CFS/CUEC, Cagliari, 2011

- ^ "Teatro Lirico Web-site". Teatroliricodicagliari.it. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ "Teatro Massimo di Cagliari". www.teatrostabiledellasardegna.it. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Scuola d'Arte Drammatica Cagliari - Tetatro stabile d'arte contemporanea Akròama". Scuoladiteatrocagliari.it. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Teatro delle Saline". Teatrodellesaline.it. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Akròama T.L.S. - Contemporary Art Theatre". Akroama.it. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Compagnia Teatrale LAPOLA". Lapola.eu. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Teatro Popolare - Teatru Populari - Progetto". teatrupopulari.figlidartemedas.org. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Centro Internazionale del Fumetto - Cagliari". Centrointernazionalefumetto.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Musei - Soprintendenza Archeologia della Sardegna". Archeocaor.beniculturali.it. 24 June 2012. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Comune di Cagliari| Museo d'Arte Siamese Stefano Cardu". Comune.cagliari.it. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Le cere anatomiche di Clemente Susini dell'Universit? Di Cagliari". pacs.unica.it. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014.

- ^ "Pinacoteca Nazionale di Cagliari - Home". Pinacoteca.cagliari.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Galleria Comunale d'Arte Cagliari". Galleriacomunalecagliari.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Ateneo - unica.it - Universitŕ degli studi di Cagliari". unica.it. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Camù Centri d'Arte e Musei". Camuweb.it. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Nostra Signora di Bonaria - Museo del Santuario di Bonaria". www.bonaria.eu. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Museo del Duomo di Cagliari". Museoduomodicagliari.it. 20 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Museo del Tesoro di Sant'Eulalia - Musei - I luoghi dell'arte e della cultura - Luoghi - Cagliari Turismo". Cagliariturismo.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Orto Botanico di Cagliari". Ccb-sardegna.it. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Cagliari, il sardo diventa lingua ufficiale: il Consiglio dice sì al nuovo Statuto - Sardiniapost". 3 November 2015.

- ^ "FIFA World Cup 1990 - Group F - Historical Football Kits". Historicalkits.co.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Tennis Club Cagliari - Home". Asdtennisclubcagliari.it. 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Amsicora - Cagliari" (in Italian). Amsicoracagliari.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Rarinantes Cagliari". Rarinantescagliari.it. 24 January 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Cagliaritana Nuoto". Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Home". Ippodromocagliari.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Centro Universitario Sportivo Cagliari : Homepage". Cuscagliari.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Home - Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici, Paesaggistici, Storici, Artistici ed Etnoantropologici per le province di Cagliari e Oristano". Sbappsaecaor.beniculturali.it. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "La Soprintendenza archivistica - Soprintendenza Archivistica per la Sardegna". Sa-sardegna.beniculturali.it. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Home - Soprintendenza Archeologia della Sardegna". Archeocaor.beniculturali.it. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Home-Page Sito web del Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo". Beniculturali.it. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Ragioneria Generale dello Stato - Ministero dell'Economia e delle Finanze". Rgs.mef.gov.it. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Classifica Atenei Statali 2012". Censismaster.it. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "AouCagliari - Presidi sanitari - Presidio Policlinico Monserrato". Aoucagliari.it. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Azienda Ospedaliera Brotzu - Home page". Aobrotzu.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Cagliariairport - it". Sogaer.it. 1 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "ARST - - Home" (in Italian). Arst.sardegna.it. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Skydive Sardegna en". Skydivesardegna.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ http://www.porto.cagliari.it/images/pdf/dati-2014[permanent dead link] st.pdf

- ^ "Acquista il biglietto con le nostre offerte". Trenitalia.com. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "CTM Cagliari". Ctmcagliari.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "ARST - - Home". Arst.sardegna.it. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Consolati | Corpo Consolare della Sardegna". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

Bibliography

- Casula, Francesco Cesare (1994). La storia di Sardegna (in Italian). Sassari: Delfino Editore. ISBN 88-7138-063-0.

- Mastino, Attilio (2006), "Carales", Brill's New Pauly Encyclopedia of the Ancient World, Leiden: Brill.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "CA´RALIS". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "CA´RALIS". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Further reading

In English:

- Andrews Robert, The Rough Guide to Sardinia, Publisher: Rough Guide Ltd, 2010, ISBN 1848365403.

- Ashby, Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 300–301.

- Dyson, Stephen L. - Roland Jr. Robert, Archaeology and History in Sardinia from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages: Shepherds, Sailors, and Conquerors, 2007.

- Freytag-Berndt, Sardinia Travel Map.

- Lawrence D. H., Sea and Sardinia

- Parker, Philip M., The 2011 Economic and Product Market Databook for Cagliari, Italy, Icon Group International, 2011 ISBN 9781157065692

- Stein Eliot, Sardinia: Cagliari & the South, Publisher: Footprint Travel Guides, United Kingdom, 2012, ISBN 1908206535

In Italian:

- Alziator Francesco, La città del sole, editrice La Zattera, Cagliari, 1963.

- Atzeni Enrico, Cagliari preistorica, editrice CUEC, Cagliari, 2003.

- Barreca Ferrucio, La Sardegna fenicia e punica, editore Chiarella, Sassari, 1984

- Boscolo Alberto, La Sardegna bizantina e altogiudicale, editotr Chiarella, Sassari, 1982

- Cossu Giuseppe, Della città di Cagliari, notizie compendiose sacre e profane, Stamperia Reale, Cagliari 1780

- Del Piano Lorenzo, La Sardegna nell'ottocento, editore Chiarella, Sassari, 1984

- Gallinari Luciano, Il Giudicato di Cagliari tra XI e XIII secolo. Proposte di interpretazioni istituzionali, in Rivista dell'Istituto di Storia dell'Europa Mediterranea, n°5, 2010

- Hunno Baeza Roderigo, Il Caralis Panegyricus, edited by Francesco Alziator, Tipografia, Mercantile Doglio, Cagliari, 1954.

- Manconi Francesco, La Sardegna al tempo degli Asburgo, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2010, ISBN 9788864290102

- Manconi Francesco, Una piccola provincia di un grande impero, CUEC, Cagliari, 2012, ISBN 8884677882

- Manconi Francesco (edited by), La società sarda in età spagnola, Edizioni della Torre, Cagliari, 2003, 2 vol.

- Mastino Attilio, Storia della Sardegna Antica, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2005, ISBN 9788889801635

- Maxia Agata Rosa, La grammatica del dialetto cagliaritano, editrice Della Torre, Cagliari, 2010

- Meloni Piero, La Sardegna Romana, Chiarella, Sassari, 1980

- Porru Vincenzo Raimondo, Saggio di gramatica sul dialetto sardo meridionale, Stamperia Reale, Cagliari, 1811.

- Scano Dionigi, Forma Karalis, a cura del Comune di Cagliari, pref. di E. Endrich, Cagliari, Società Editrice Italiana, 1934, (oggi in ed. anast. Cagliari, La zattera, 1970; Cagliari, 3T, 1989).

- Sole Carlino, La Sardegna sabauda nel settecento, edizione Chiarella, Sassari, 1984

- Sorgia Giancarlo, La Sardegna spagnola, editore Chiarella, Sassari, 1983

- Spano Giovanni, Guida della città e dintorni di Cagliari, ed. Timon, Cagliari, 1861

- Spanu Luigi, Cagliari nel seicento, editrice Il Castello, Cagliari, 1999

- Thermes Cenza, Cagliari, amore mio : guida storica, artistica, sentimentale della citta di Cagliari, editrice 3T, Cagliari, 1980–81.

- Thermes Cenza, E a dir di Cagliari..., editrice G. Trois, Cagliari, 1997.

- Zedda Corrado, Pinna Raimondo, Fra Santa Igia e il Castro Novo Montis de Castro. La questione giuridica urbanistica a Cagliari all'inizio del XIII secolo, Archivio Storico Giuridico Sardo di Sassari", n.s., 15 (2010–2011), pp. 125–187

External links

- Official website

(in Italian)

(in Italian) - Cagliari Tourist Board website Archived 23 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Archdiocese of Cagliari". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Archdiocese of Cagliari". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sardinia". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sardinia". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.