Feodosia

Feodosia | |

|---|---|

Genoese fortress of Caffa | |

| Coordinates: 45°02′03″N 35°22′45″E / 45.03417°N 35.37917°E | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous republic | Crimea (de jure) |

| Raion | Feodosia Raion (de jure) |

| Federal subject | Crimea (de facto) |

| Municipality | Feodosia Municipality (de facto) |

| Elevation | 50 m (160 ft) |

| Population (2015) | |

• Total | 69,145 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK) |

| Postal codes | 298100–298175 |

| Area code | +7-36562 |

| Former names | Kefe (until 1784), Caffa (until the 15th century) |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Website | feo |

| |

Feodosia (Ukrainian: Феодосія, Теодосія, Feodosiia, Teodosiia; Russian: Феодосия, Feodosiya[1]), also called in English Theodosia (from Greek: Θεοδοσία), is a city on the Crimean coast of the Black Sea. Feodosia serves as the administrative center of Feodosia Municipality, one of the regions into which Crimea is divided. During much of its history, the city was a significant settlement known as Caffa (Ligurian: Cafà) or Kaffa (Old Crimean Tatar/Ottoman Turkish: کفه; Crimean Tatar/Turkish: Kefe). According to the 2014 census, its population was 69,145.

History

Theodosia (Greek colony)

The city was founded as Theodosia (Θεοδοσία) by Greek colonists from Miletos in the 6th century BC. Noted for its rich agricultural lands, on which its trade depended, the city was destroyed by the Huns in the 4th century AD.

Theodosia remained a minor village for much of the next nine hundred years. It was at times part of the sphere of influence of the Khazars (excavations have revealed Khazar artifacts dating back to the 9th century) and of the Byzantine Empire.

Like the rest of Crimea, this place (village) fell under the domination of the Kipchaks and was conquered by the Mongols in the 1230s.

A settlement named Kaphâs (alternate romanized spelling Cafâs, Greek: Καφᾶς) existed surrounding Theodosia prior to the penetration of Genoese into the Black Sea. The archaeological evidence indicates that during the Middle Ages the population about Theodosia never decreased to zero; several medieval churches are found in the area dating from the times of Late Antiquity/Early Middle Ages. However, the population had become completely agrarian. A small local Greek population must have existed in situ and in the neighboring settlements. Likely, from the 9th century there were Cumans and Goths living alongside the Greeks, and by 1270s, perhaps some Tatars and Armenians as well.[2]

Kaffa (Genoese colony)

In the late 13th century, traders from the Republic of Genoa arrived and purchased the city from the ruling Golden Horde.[3]

They established a flourishing trading settlement called Kaffa (also recorded as Caffa), which virtually monopolized trade in the Black Sea region and served as a major port and administrative center for the Genoese settlements around the Sea. The city thrived despite the tenuous politics of the region and Genoa's series of wars with the Mongol successor states.[4]

It came to house one of Europe's biggest slave markets of the Black Sea slave trade, and served as a terminus for the Silk Road. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia also adds that the city of Caffa was established during the times when the area was ruled by the Khan of the Golden Horde Mengu-Timur.[5]

Ibn Battuta visited the city, noting it was a "great city along the sea coast inhabited by Christians, most of them Genoese." He further stated, "We went down to its port, where we saw a wonderful harbor with about two hundred vessels in it, both ships of war and trading vessels, small and large, for it is one of the world's celebrated ports."[6]

In early 1318, Pope John XXII established a Latin Church diocese of Kaffa, as a suffragan of Genoa. The papal bull of appointment of the first bishop attributed to him a vast territory: "a villa de Varna in Bulgaria usque Sarey inclusive in longitudinem et a mari Pontico usque ad terram Ruthenorum in latitudinem" ("from the city of Varna in Bulgaria to Sarey inclusive in longitude, and from the Black Sea to the land of the Ruthenians in latitude"). The first bishop was Fra' Gerolamo, who had already been consecrated seven years before as a missionary bishop ad partes Tartarorum. The diocese ended as a residential bishopric with the capture of the city by the Ottomans in 1475.[7][8][9] Accordingly, Kaffa is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[10] The new diocese effectively broke up the diocese of Khanbaliq, which functioned as one diocese for all Mongol territory from the Balkans to China.[11]

It is believed that the devastating pandemic of the Black Death entered Europe for the first time via Kaffa in 1347. After a protracted siege during which the Mongol army under Janibeg was reportedly withering from the disease, they catapulted the infected corpses over the city walls, infecting the inhabitants, in one of the first cases of biological warfare. Fleeing inhabitants may have carried the disease back to Italy, causing its spread across Europe. However, the plague appears to have spread in a stepwise fashion, taking over a year to reach Europe from Crimea. Also, there were a number of Crimean ports under Mongol control, so it is unlikely that Kaffa was the only source of plague-infested ships heading to Europe. Additionally, there were overland caravan routes from the East that would have been carrying the disease into Europe as well.[12][13]

Kaffa eventually recovered. The thriving, culturally diverse city and its thronged slave market have been described by the Spanish traveler Pedro Tafur, who was there in the 1430s.[14] The port was also visited by German traveler Johann Schiltberger in the 15th century.[4] In 1462, Caffa placed itself under the protection of King Casimir IV of Poland.[15] However, Poland did not offer significant help due to reinforcements sent being massacred in Bar fortress (modern day Ukraine) by Duke Czartoryski after a quarrel with locals.[citation needed]

Kefe (Ottoman)

Following the fall of Constantinople, Amasra, and lastly Trebizond, the position of Caffa had become untenable and attracted the attention of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II. He was at no loss for a pretext to extinguish this last Genoese colony on the Black Sea. In 1473, the tudun (or governor) of the Crimean Khanate died and a fight developed over the appointment of his successor. The Genoese involved themselves in the dispute, and the Tatar notables who favored the losing candidate finally asked Mehmed to settle the dispute.

Mehmed dispatched a fleet under the Ottoman commander Gedik Ahmet Pasha, which left Constantinople 19 May 1475. It anchored before the walls of the city on 1 June, started the bombardment the next day, and on 6 June the inhabitants capitulated. Over the next few days the Ottomans proceeded to extract the wealth of the inhabitants, and abduct 1,500 youths for service in the Sultan's palace.[unbalanced opinion?] On 8 July, the final blow was struck when all inhabitants of Latin origin were ordered to relocate to Istanbul, where they founded a quarter (Kefeli Mahalle) which was named after the town they had been forced to leave.[16]

Renamed Kefe, Caffa became one of the most important Turkish ports on the Black Sea. It was a major center of the Crimean slave trade until the late 18th-century, referred to by the Lithuanian Mikhalon Litvin as: "not a town, but an abyss into which our blood is pouring".[17] In 1616, Zaporozhian Cossacks under the leadership of Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny destroyed the Turkish fleet and captured Caffa. Having conquered the city, the Cossacks released the men, women and children who were slaves.

Feodosia (Russian Empire)

Ottoman control ceased when the expanding Russian Empire took over Crimea between 1774 and 1783. It was renamed Feodosia (Russian Ѳеодосія; reformed spelling Феодосия), after the traditional Russian reading of its ancient Greek name. In 1900, Zibold constructed the first air well (dew condenser) on mount Tepe-Oba near Feodosia.[citation needed]

Soviet Union

WWII and Holocaust

The city was occupied by the forces of Nazi Germany during World War II, sustaining significant damage in the process. The Jewish population numbering 3,248 before the German occupation was murdered by SD-Einsatzgruppe D between November 16 and December 15, 1941.[18] A witness interviewed by the Soviet Extraordinary Commission in 1944 and quoted on the website of the French organization Yahad-In Unum described how the Jews were rounded-up in the city:

[A]ll the Jews were gathered. The Germans told them they would be displaced somewhere in Ukraine. On December 4, 1941, in the morning, all the Jews, including my father, my mother and my sister were taken to an anti-tank trench where they were executed by German shooters. 1,500-1,700 people were shot that day.[19]

A monument commemorating the Holocaust victims is situated at the crossroads of Kerchensky and Symferopolsky highways. On Passover eve, 7 April 2012, unknown persons desecrated the monument for the sixth time in what was allegedly an anti-Semitic act.[20]

All native Tatar inhabitants were arrested by Soviet forces as several thousand Tatars had fought side-by-side with the Nazis against Soviet forces and had participated in the Jewish genocide.[21] Following Stalin's orders, all Tatars were sent to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and other Central Asian republics of the USSR.

Ukraine

Russian occupation

During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian warship Novocherkassk, a landing ship likely used to transport drones, was hit in the early morning hours of 26 December 2023 in the harbour of Feodosia. There was a large fire and explosion. Russia reported that two missiles that were fired from Sukhoi Su-24 jets were shot down.[22]

Geography

Climate

The climate is warm and dry and could be described as humid subtropical, but not as Mediterranean, because the drying summer trend is not pronounced enough.

| Climate data for Feodosia (1991–2020, extremes 1881–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.5 (81.5) |

31.9 (89.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

38.9 (102.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

38.9 (102.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.9 (40.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.6 (85.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

2.4 (36.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.1 (39.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.0 (−13.0) |

−25.1 (−13.2) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−18.6 (−1.5) |

−25.1 (−13.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43 (1.7) |

36 (1.4) |

38 (1.5) |

32 (1.3) |

41 (1.6) |

43 (1.7) |

33 (1.3) |

41 (1.6) |

43 (1.7) |

41 (1.6) |

41 (1.6) |

46 (1.8) |

478 (18.8) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 1 (0.4) |

2 (0.8) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

2 (0.8) |

| Average rainy days | 12 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 111 |

| Average snowy days | 8 | 8 | 6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 2 | 6 | 31 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81.3 | 79.2 | 77.1 | 73.4 | 70.5 | 68.3 | 63.5 | 64.3 | 70.0 | 76.5 | 80.8 | 82.0 | 73.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63 | 72 | 129 | 182 | 252 | 283 | 308 | 287 | 246 | 166 | 85 | 51 | 2,124 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net,[23] NOAA NCEI (humidity 1981–2010)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, 1961−1990)[25] | |||||||||||||

Modern Feodosia

Modern Feodosia is a resort city with a population of about 69,000 people. It has beaches, mineral springs, and mud baths, sanatoria, and rest homes. Apart from tourism, its economy rests on agriculture and fisheries. Local industries include fishing, brewing and canning. As with much of the Crimea, most of its population is ethnically Russian; the Ukrainian language is infrequently used. In June 2006, Feodosia made the news with the 2006 anti-NATO protests.

While most beaches in the Crimea are made of pebbles, in the Feodosia area there is a unique Golden Beach (Zolotoy Plyazh) made of small seashells which stretches for some 15 km.

The city is sparsely populated during the winter months and most cafes and restaurants are closed. Business and tourism increase in mid-June and peak during July and August. As in the other resort towns of the Crimea, the tourists come mostly from the Commonwealth of Independent States countries of the former Soviet Union.

Feodosia was the city where the seascape painter Ivan Aivazovsky lived and worked all his life, and where general Pyotr Kotlyarevsky and the writer Alexander Grin spent their declining years. Popular tourist locations include the Aivazovsky National Art Gallery and the Genoese fortress.

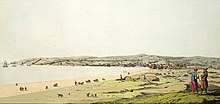

- View from Tepe-Oba

- Ancient Karaites cemetery

- Genoese castle Caffa

- Port and Tepe-Oba

- Lighthouse on Tepe-Oba

- Feodosia city centre

Economy

- More PO (Primorsk)

- Sudokompozit - ship design R&D naval hardware

- Kasatka TsNII Gp NPO Uran (Gagra Pitsunda) - ship design R&D naval hardware

- Gidropribor FeOMMZ, torpedo manufacturing and ship yard (Ordzhonikidze)

- NPO Uran TsNII Gp "Kasatka" (Lab N°5 NII400) torpedoes (Gagra Pitsunda)

- Russia Black Sea Fleet Navy Ship repair Yards

- FOMZ Opto Mechanical Plant FKOZ

- Feodosia Economic Industrial Zone FPZ (west)

- Feodosia FMZ Engineering/Machine-building Plant

- Feodosia FPZ (Priborostroeni Priladobudivni) Instrument-making Plant

Twin towns—sister cities

People from Feodosia

- Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900), Russian painter

- Yuriy Barashian (born 1979), Ukrainian boxer

- Serhiy Derevyanchenko (born 1985), Ukrainian boxer

- Roman Kapitonenko (born 1981), Ukrainian boxer

- Tetyana Kozyrenko (born 1996), Ukrainian football player

- Wolff Kostakowsky (1879-1944), American klezmer violinist

- Andrzej Liczik (born 1977), Ukrainian-Polish boxer

In popular culture

The late-medieval city of Caffa is the location of a section of the novel Caprice and Rondo by the Scottish novelist Dorothy Dunnett.

An early 14th-century bishop of Caffa appears in Umberto Eco's novel The Name of the Rose, making several sharp replies in a long, tempestuous debate within a group of monks and clerics; he is portrayed as aggressive and somewhat narrow-minded.

See also

References

- ^ Про впорядкування транслітерації українського алфавіту... | від 27.01.2010 № 55

- ^ Khvalkov, Ievgen Alexandrovitch, The Colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea Region: Evolution and Transformation, European University Institute, Department of History and Civilization, Florence, vol. 1, pg. 83, September 2015,

- ^ Khvalkov, I.E., The Colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea Region: Evolution and Transformation,European University Institute, Department of History and Civilization,Florence, 8 September 2015

- ^ a b Slater, Eric (2006). "Caffa: Early Western Expansion in the Late Medieval World, 1261-1475". Review (Fernand Braudel Center). 29 (3): 271–283. ISSN 0147-9032. JSTOR 40241665.

- ^ Mengu-Timur (Менгу-Тимур). Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Accessed 26 February 2024.

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, pg. 432

- ^ Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 1 Archived 9 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 154–155; vol. 2 Archived 2018-10-04 at the Wayback Machine, pp. XVIII e 117; vol. 3 Archived 21 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, pg. 145; vol. 5, p. 134

- ^ Gasparo Luigi Oderico, Lettere ligustiche ossia Osservazioni critiche sullo stato geografico della Liguria fino ai Tempi di Ottone il Grande, con le Memorie storiche di Caffa ed altri luoghi della Crimea posseduti un tempo da' Genovesi, Bassano 1792 (especially p. 166 ff.)

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013; ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 855

- ^ Khvalkov, Evgeny (2017). The colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea region : evolution and transformation. New York. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-351-62306-3. OCLC 994262849.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wheelis, Mark (September 2002). "Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Kaffa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (9): 971–75. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530. PMID 12194776.

- ^ Frankopan, Peter. The Silk Roads. p. 183.

A Mongol army laying siege to the Genoese trading post of Caffa following a dispute about trade terms was annihilated by illness that killed 'thousands and thousands every day,' according to one commentator. Before withdrawing, however, 'they ordered corpses to be placed in catapults and lobbed into the city in the hope that the intolerable stench would kill everyone inside.' Rather than being overwhelmed by the smell, it was the highly contagious disease that caught hold. Unknowingly, the Mongols had turned to biological warfare to defeat their enemy. The trading routes that connected Europe to the rest of the world now became lethal highways for the transmission of the Black Death. In 1347, the disease reached Constantinople and then Genoa, Venice and the Mediterranean, brought by traders and merchants fleeing home.

- ^ Tafur, Andanças e viajes

- ^ D. Kołodziejczyk, The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania. International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th–18th Century) A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by Annotated Documents, Leiden - Boston 2011, p. 62; ISSN 1380-6076 / ISBN 978 90 04 19190 7

- ^ Franz Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time (Princeton: University Press, 1978).

- ^ Davies, Brian (2014). Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 1500–1700. Routledge; ISBN 978-1-134-55283-2. pp. 24-25

- ^ Martin Gilbert, The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust, 2002, pp.64, 83

- ^ "Execution of Jews in Feodosiya". The Map of Holocaust by Bullets (interactive map). Yahad-In Unum. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "ФЕОДОСИЯ. Осквернен памятник жертвам Холокоста". Всеукраинский Еврейский Конгресс. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "РУКОВОДСТВО ПАРТИЗАНСКИМ ДВИЖЕНИЕМ КРЫМА В 1941—1942 ГОДАХ И "ТАТАРСКИЙ ВОПРОС"". Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Russisches Kriegsschiff vor Krim getroffen orf.at, 26 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023 (German).

- ^ "Weather and Climate-The Climate of Feodosia" (in Russian). Weather and Climate. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010" (CAV). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (CSV) on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Feodosija Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

Further reading

- Annette M. B. Meakin (1906). "Theodosia". Russia, Travels and Studies. London: Hurst and Blackett. OCLC 3664651. OL 24181315M.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Гавриленко О. А., Сівальньов О. М., Цибулькін В. В. Генуезька спадщина на теренах України; етнодержавознавчий вимір. — Харків: Точка, 2017.— 260 с. — ISBN 978-617-669-209-6

- Khvalkov E. The colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea region: evolution and transformation. L., New York : Routledge, 2017[1]

- Khvalkov E. Evoluzione della struttura della migrazione dei liguri e dei corsi nelle colonie genovesi tra Trecento e Quattrocento. In: Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria, Nuova Serie'. 2017. Vol. 57 / 131 . -pp. 67–79.

- Khvalkov E. I piemontesi nelle colonie genovesi sul Mar Nero: popolazione del Piemonte a Caffa secondo i dati delle Massariae Caffae ad annum del 1423 e del 1461. In: Studi Piemontesi. 2017. No. 2. pp. 623–628.

- Khvalkov E. Campania, Puglia e Basilicata nella colonizzazione genovese dell'Oltremare nei secoli XIV – XV: Caffa genovese secondo i dati dei libri contabili. In: Rassegna Storica Salernitana. 2016. Vol. 65. pp. 11–16.

- Khvalkov E. Italia settentrionale e centrale nel progetto coloniale genovese sul Mar Nero: gente di Padania e Toscana a Caffa genovese nei secoli XIII – XV secondo i dati delle Massariae Caffae ad annum 1423 e 1461. In: Studi veneziani. Vol. LXXIII, 2016. - pp. 237–240.[2]

- Khvalkov E. Il progetto coloniale genovese sul Mar Nero, la dinamica della migrazione latina a Caffa e la gente catalanoaragonese, siciliana e sarda nel Medio Evo. In: Archivio Storico Sardo. 2015. Vol. 50. No. 1. pp. 265–279.[3][4]

- Khvalkov E. Il Mezzogiorno italiano nella colonizzazione genovese del Mar Nero a Caffa genovese nei secoli XIII – XV (secondo i dati delle Massariae Caffae) (pdf). In: Archivio Storico Messinese. 2015. Vol. 96 . - pp. 7–11.[5]

External links

Media related to Feodosia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Feodosia at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of feodosia at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of feodosia at Wiktionary- WorldStatesmen- Ukraine

- Ancient Theodosia and its Coinage

- Tourist Theodosius

- The murder of the Jews of Feodosia Archived 2015-05-19 at the Wayback Machine during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.

- ^ Khvalkov, Evgeny (2017). The Colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea Region: Evolution and Transformation. Routledge Research in Medieval Studies. L, NY: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. p. 444. ISBN 9781138081604. LCCN 2017028228.

- ^ Khvalkov, Evgeny (2019). "Italia settentrionale e centrale nel progetto coloniale genovese sul Mar Nero: gente di Padania e Toscana a Caffa genovese nei secoli XIII – XV secondo i dati delle Massariae Caffae ad annum 1423 e 1461. In: Studi veneziani. 2016. Vol. 73. P. 237-240. Khvalkov E." SPb HSE (in Italian). Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ Khvalkov, Evgeny A. (2015). "Il progetto coloniale genovese sul Mar Nero, la dinamica della migrazione latina a Caffa e la gente catalanoaragonese, siciliana e sarda nel Medio Evo" (PDF). Archivio Storico Sardo (in Italian). 50 (1). Deputazione di Storia Patria per la Sardegna. www.deputazionestoriapatriasardegna.it: 265–279. ISSN 2037-5514.

- ^ "KVK-Volltitel". kvk.bibliothek.kit.edu. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Società Messinese di Storia Patria. Archivio Storico Messinese, Volume 96". www.societamessinesedistoriapatria.it. 2015. Retrieved 2019-10-21.