Bisantrene

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

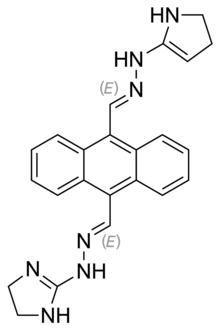

| Formula | C22H22N8 |

| Molar mass | 398.474 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Bisantrene is an anthracenyl bishydrazone with anthracycline-like antineoplastic activity and an antimetabolite.[1] Bisantrene intercalates with and disrupts the configuration of DNA, resulting in DNA single-strand breaks, DNA-protein crosslinking, and inhibition of DNA replication. This agent is similar to doxorubicin in chemotherapeutic activity, but unlike anthracyclines like doxorubicin, it exhibits little cardiotoxicity.[2]

In addition to its anthracycline-like activity, a July 2020 seminal article by Su, R et al. at the City of Hope Hospital in Los Angeles, California, USA first identified bisantrene to also be a potent (IC50 = 142nM) inhibitor of the Fat Mass and Obesity (FTO) associated protein, which is a m6A RNA demethylase. The same study found that bisantrene is a weak inhibitor of ALKBH5, which is the only other demethylase, i.e. bisantrene is also a selective inhibitor of FTO.[3]

In 2021, bisantrene was demonstrated preclinically to be cardioprotective when administered together with cardiotoxic anthracyclines.[4]

A bisantrene combination treatment is currently (as at early 2024) nearing the end of a Phase II clinical trial to assess its efficacy in treating AML in heavily pretreated patients and to assess any adverse side effects, including any cardiotoxicity of the combination. The December 2023 interim findings are given in the History section.[5]

Medical uses

Clinical trials of Bisantrene in the 1980s showed efficacy in a range of leukaemias (including Acute Myeloid Leukaemia), breast cancer, and ovarian cancer.[6]

Adverse Side Effects

High doses of bisantrene (above 200 mg/m2/day) cause adverse side effects typical of anthracycline chemotherapeutics. Common adverse side effects include hair loss, bone marrow suppression, vomiting, rash, and inflammation of the mouth. For a chemotherapy drug, it is considered to have relatively low toxicity.[7]

Unlike other anthracycline chemotherapeutics, Bisantrene shows low levels of cardiotoxicity. In a Phase III metastatic breast cancer clinical, patients were exposed to cumulative doses in excess of 5440 mg/m2 without developing cardiac damage.[medical citation needed][6] The same study observed significantly lower rates of hair loss and nausea compared to patients given doxorubicin.[8]

Three Mechanisms of Action

Bisantrene has three distinct mechanisms of action.

Bisantrene contains an appropriately sized planar electron-rich chromophore to be a DNA intercalating agent, and in vitro, it is a potent inhibitor of DNA and RNA synthesis.[6][7]

Bisantrene is also a potent and selective inhibitor of the FTO enzyme, which is an m6A mRNA demethylase. Bisantrene acts by occupying FTO's catalytic pocket. This is a relatively recent discovery (July 2020).[3]

Finally, the University of Newcastle and the Hunter Medical Research Institute found in late 2021 preclinical research that bisantrene has a cardioprotective mechanism of action when administered together with a cardiotoxic drug such as doxorubicin. As at early 2024, the molecular basis for this cardioprotective effect hasn't been announced by the researchers.[4]

Bisantrene's cardioprotective mechanism of action is important because "15 of the 35 commercially available anti-cancer drugs have direct cardiotoxic effects on HCM (human cardiomyocytes)."[9]

According to the Australian Cardiovascular Alliance Cardio-Oncology Working Group , a drug which is simultaneously anticancer and cardioprotective is the "Holy Grail" of Cardio-Oncology.[10]

History

Bisantrene was developed by Lederle Laboratories during the 1970s, a subsidiary of American Cyanamid, as a less cardiotoxic alternative to anthracyclines. Across the 1980s and early 1990s, over 40 clinical trials were conducted using Bisantrene. The National Cancer Institute (NCI)] undertook a large scale trial using Bisantrene under the name "Orange Crush", including a range of preclinical trials which found bisantrene to be inactive when taken orally, though was found to be efficacy towards some cancer cells intravenous, intraperitoneal, or subcutaneous.[medical citation needed]

In the 1980s, forty-four patients with metastatic breast cancer who had undergone extensive combination chemotherapy with doxorubicin and had failed to respond to the combination, were treated with bisantrene. From 40 patients that were evaluated, 9 showed a partial response, and 18 showed the cancer was not progressive but stabilised.[11]

Bisantrene was approved for human medical use in France in 1990 to target Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) cancers.[citation needed]

It has undergone 46 Phase II trials with 1,800 patients to test its efficacy against fighting cancer cells.[citation needed]

The drug was delisted in the early 1990s due to a series of pharmaceutical mergers and acquisitions.[citation needed]

In November 2019, researchers at the City of Hope Hospital in Los Angeles, California published that a drug with codename "CS1" is a potent and specific inihibitor of FTO, a m6A mRNA demethylase. This article didn't identify that "CS1" is actually bisantrene.[12]

In 2020 at Sheba Hospital, Tel Aviv, Israel, four out of 10 heavily pretreated AML patients responded to bisantrene administered as a single agent. All four of these responding patients had extramedullary disease.[13]

In July 2020, researchers at the City of Hope Hospital in Los Angeles, California published that bisantrene (for which they mostly used the codename "CS1") is a potent and specific inihibitor of FTO, a m6A mRNA demethylase. The fact that "CS1" is actually bisantrene is mentioned near the start of the Discussion section of the article.[3]

In 2021, researchers at the University of Chicago used bisantrene (which they referred to as "CS1", using the codename adopted by the City of Hope Hospital) to successfully inhibit FTO in a preclinical experiment.[14]

In a preclinical trial published in January 2022, researchers at the University of Lille used bisantrene to inhibit FTO in order to test whether an FTO inhibitor could potentially be used to treat disregulation of glucose metabolism in Type 2 diabetes.[15]

In 2022 researchers at the University of Texas tested a bisantrene, venetoclax and decitabine combination for AML preclinically.[16]

Based on the 2020 clinical study at Sheba Hospital and the two University of Texas pre-clinicals cited above, the most recent clinical trial is the one currently (as at early 2024) underway as a combination treatment for AML in heavily pretreated patients at Sheba Hospital, Tel Aviv, Israel. In the dose-finding stage, three out of six of the heavily pretreated patients were bridged to a bone marrow transplant.[17] Interim results of the expansion stage were announced in December 2023 in a poster presented at the 2023 American Society of Haematologists conference. The results are promising for such heavily pre-treated patients. Six patients recovered sufficiently to be bridged to a bone marrow transplant. No cardiotoxity of the Bisantrene, Fludarabine and Clofarabin combination was observed.[5]

In November 2023, researchers at the University of Newcastle and at Race Oncology Limited jointly published a preclinical study in the peer-reviewed journal Blood. It found that bisanantrene is synergistic with the hypomethalating agent decitabine for treatment of AML. The researchers recommended that this combination should proceed to the clinic.[18]

Alternate Names for Bisantrene

Names

Bisantrene's chemical name is 9, 10-antrhracenedicarboxaldehydebis [(4, 5-dihydro-1H-imidazole-2-yl) hydrazine] dihydrochloride.

Bisantrene was given the nickname “Orange Crush” in the 1980s due to its fluorescent orange color when in solution.[19]

Bisantrene is also sometimes referred to as "CS1" in cancer research journals, starting with the July 2020 seminal article by Su, R et al. The fact that "CS1" is actually bisantrene is mentioned near the start of the Discussion section of that article.[3]

References

- ^ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. p. 126. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ "Bisantrene". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ^ a b c d Su R, Dong L, Li Y, Gao M, Han L, Wunderlich M, et al. (July 2020). "Targeting FTO Suppresses Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance and Immune Evasion" (PDF). Cancer Cell. 38 (1): 79–96.e11. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.017. PMC 7363590. PMID 32531268.

- ^ a b NSW Regional Health Partners (2022). "Professor Doan Ngo awarded for her game changing cancer discovery".

- ^ a b Danylesko, I (11 December 2023). "Bisantrene in Combination with Fludarabine and Clofarabine As Salvage Therapy for Adult Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)- an Open-Label, Phase II, Study".

- ^ a b c Spiegel (January 1982). "Phase I Clinical Trial of 9,10-Anthracene Dicarboxaldehyde (Bisantrene) Administered in a Five-Day Schedule". Cancer Research. 42 (1): 354–358. PMID 7053862.

- ^ a b Testa B (2013-10-22). Advances in Drug Research. Elsevier. pp. 69–72. ISBN 978-1-4832-8798-0.

- ^ Cowan JD, Neidhart J, McClure S, Coltman CA, Gumbart C, Martino S, et al. (August 1991). "Randomized trial of doxorubicin, bisantrene, and mitoxantrone in advanced breast cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 83 (15): 1077–1084. doi:10.1093/jnci/83.15.1077. PMID 1875415.

- ^ Balachandran, L (15 February 2024). "Cancer Therapies and Cardiomyocyte Viability: Which Drugs are Directly Cardiotoxic?". Heart, Lung and Circulation. 33 (5): 747–752. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2024.01.013. PMID 38365500.

- ^ Singleton, Anna C (9 February 2024). "Integrating CardioOncology Across the Research Pipeline, Policy, and Practice in Australia—An Australian Cardiovascular Alliance Perspective". Heart, Lung and Circulation. 33 (5): 564–575. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2024.01.011. PMID 38336544.

- ^ Yap HY, Yap BS, Blumenschein GR, Barnes BC, Schell FC, Bodey GP (March 1983). "Bisantrene, an active new drug in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer" (PDF). Cancer Research. 43 (3): 1402–1404. PMID 6825109.

- ^ Su, Rui (13 November 2019). "Effective Novel Fto Inhibitors Show Potent Anti-Cancer Efficacy and Suppress Drug Resistance". Blood. 134 (134, Supplement 1): 233. doi:10.1182/blood-2019-124535.

- ^ Canaani, J (6 November 2020). "A phase II study of bisantrene in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia". European Journal of Haematology. 106 (2): 260–266. doi:10.1111/ejh.13544. PMID 33159365. S2CID 226275414.

- ^ Cui, Yan-Hong (2021). "Autophagy of the m6A mRNA demethylase FTO is impaired by low-level arsenic exposure to promote tumorigenesis". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 2813. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22469-6. PMC 8041927. PMID 33846348.

- ^ Bornaque, Florian (15 January 2022). "Glucose Regulates m6A Methylation of RNA in Pancreatic Islets". Cells. 11 (2): 291. doi:10.3390/cells11020291. PMC 8773766. PMID 35053407.

- ^ Valdez, Benigno C (2022). "Enhanced cytotoxicity of bisantrene when combined with venetoclax, panobinostat, decitabine and olaparib in acute myeloid leukemia cells". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 63 (7): 1634–1644. doi:10.1080/10428194.2022.2042689. PMID 35188042.

- ^ "Zantrene May Promote Long-term Remission in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients, Sheba Study Indicates". 4 May 2023.

- ^ Verrills, Nicole M (November 2023). "Preclinical Evaluation of Bisantrene As Single Agent and in Combination with Decitabine for Acute Myeloid Leukemia". Blood. 142 (142 (Supplement 1)): 5773. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-188353.

- ^ "Bisantrene Hydrochloride (Code C77218)". NCI Thesaurus. National Cancer Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 28 June 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-07-12. Retrieved 12 July 2021.