Bhikkhunī

| Translations of 𑀪𑀺𑀓𑁆𑀔𑀼𑀦𑀻 | |

|---|---|

| English | Nun |

| Sanskrit | भिक्षुणी (IAST: bhikṣuṇī) |

| Pali | 𑀪𑀺𑀓𑁆𑀔𑀼𑀦𑀻 (bhikkhunī) |

| Burmese | ဘိက္ခုနီ (MLCTS: beiʔkʰṵnì) |

| Chinese | 比丘尼 (Pinyin: bǐqiūní) |

| Japanese | 比丘尼/尼 (Rōmaji: bikuni/ama) |

| Khmer | ភិក្ខុនី (UNGEGN: phĭkkhŏni) |

| Korean | 비구니 (RR: biguni) |

| Sinhala | භික්ෂුණිය (bhikṣuṇiya) |

| Tibetan | དགེ་སློང་མ་ (gelongma (dge slong ma)) |

| Tagalog | Bhikkhuni |

| Thai | ภิกษุณี [th] ([pʰiksuniː]) |

| Vietnamese | tỳ kheo ni |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

A bhikkhunī (Pali: 𑀪𑀺𑀓𑁆𑀔𑀼𑀦𑀻) or bhikṣuṇī (Sanskrit: भिक्षुणी) is a Buddhist nun, fully ordained female in Buddhist monasticism. Bhikkhunīs live by the Vinaya, a set of either 311 Theravada, 348 Dharmaguptaka, or 364 Mulasarvastivada school rules. Until recently, the lineages of female monastics only remained in Mahayana Buddhism and thus were prevalent in countries such as China, Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Vietnam, while a few women have taken the full monastic vows in the Theravada and Vajrayana schools. The official lineage of Tibetan Buddhist bhikkhunīs recommenced on 23 June 2022 in Bhutan when 144 nuns, most of them Butanese, were fully ordained.[1][2]

According to the Buddhist Canon, women are as capable of reaching enlightenment as men.[3] The Canon describes that the order of bhikkhunīs was first created by the Buddha at the specific request of his aunt and foster-mother Mahapajapati Gotami, who became the first ordained bhikkhunī. A famous work of the early Buddhist schools is the Therigatha, a collection of poems by elder nuns about enlightenment that was preserved in the Pāli Canon. The canon also describes extra vows required for women to be ordained as bhikkhunīs.

In the Vajrayana of Tibetan Buddhism, Guru Padmasambhava stated that being a woman was actually better than being a man:[4][5]

"The basis for realizing enlightenment is a human body. Male or female – there is no great difference. But if she develops the mind bent on enlightenment, to be a woman is better."

— Guru Padmasambhava

The historical authorship of the controversial Eight Garudhammas cannot be traced to the Buddha.[6][7][8] Written by others at a later date, it mandated the bhikkhunī order to be subordinate to and reliant upon the bhikkhu (monk) order.[9] There are 253 Vinaya precepts for bhikkus. In places where the bhikkhunī lineage was historically absent or has died out due to hardship, alternative forms of renunciation have developed.

In Tibetan Buddhism, women first officially take refuge vows as a layperson. Then, the renunciate vows of rabtu jungwa (rab-jung) are given before the getsulma (Tibetan novice) ordination vows are given. After these, full bhikkhunī ordination may be given.[10]

Theravadan women may choose to take an informal and limited set of vows similar to the historical vows of the getsulma (Sanskrit sāmaṇerī), like the maechi of Thailand and thilashin of Myanmar.

History

The tradition of the ordained monastic community (sangha) began with the Buddha, who established an order of bhikkhus (monks).[11] According to the scriptures,[12] later, after an initial reluctance, he also established an order of Bhikkhunis (nuns or women monks). However, according to the scriptural account, not only did the Buddha lay down more rules of discipline for the bhikkhunīs (311 compared to the bhikkhu's 227 in the Theravada version), he also made it more difficult for them to be ordained, and made them subordinate to monks.[13] The bhikkhunī order was established five years after the bhikkhu order at the request of a group of women whose spokesperson was Mahapajapati Gotami, the aunt who raised Gautama Buddha after his mother died.[13]

The historicity of this account has been questioned,[14] sometimes to the extent of regarding nuns as a later invention.[15] The stories, sayings and deeds of a substantial number of the preeminent bhikkhunī disciples of the Buddha as well as numerous distinguished bhikkhunīs of early Buddhism are recorded in many places in the Pali Canon, most notably in the Therigatha and Theri Apadana as well as the Anguttara Nikaya and Bhikkhuni Samyutta. Additionally the ancient bhikkhunīs feature in the Sanskrit Avadana texts and the first Sri Lankan Buddhist historical chronicle, the Dipavamsa, itself speculated to be authored by the Sri Lankan bhikkhunī Sangha.[citation needed] Not only normal women, many Queens and princesses left their luxurious life to become bhikkhunīs to have spiritual attainment. According to legend, the former wife of Buddha—Yasodharā, mother of his son Rāhula—also became a bhikkhunī and an arahant.[16] Queen Khema one of the consorts of king Bimbisara became a bhikkhunī and to hold the title of first foremost disciple of Gautam Buddha. Mahapajapati Gotami's daughter princess Sundari Nanda became a bhikkhunī and an attained arhat.

According to Peter Harvey, "The Buddha's apparent hesitation on this matter is reminiscent of his hesitation on whether to teach at all", something he only does after persuasion from various devas.[17] Since the special rules for female monastics were given by the founder of Buddhism they have been upheld to this day. Buddhists nowadays are still concerned with that fact, as shows at an International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha held at the University of Hamburg, Germany, in 2007.[citation needed]

In Buddhism, women can openly aspire to and practice for the highest level of spiritual attainment. Buddhism is unique among Indian religions in that the Buddha as founder of a spiritual tradition explicitly states in canonical literature that a woman is as capable of nirvana as men and can fully attain all four stages of enlightenment.[18][19] There is no equivalent in other traditions to the accounts found in the Therigatha or the Apadanas that speak of high levels of spiritual attainment by women.[20]

In a similar vein, major canonical Mahayana sutras such as the Lotus Sutra, chapter 12,[21] records 6,000 bhikkhunī arhants receiving predictions of bodhisattvahood and future buddhahood by Gautama Buddha.[21]

The Eightfold Paths

According to the Buddhist Canon, female monastics are required to follow special rules that male monastics do not, the Eight Garudhammas. Their origin is unclear; the Buddha is quoted by Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu as saying, "Ananda, if Mahaprajapati Gotami accepts eight vows of respect, that will be her full ordination (upasampada)."[22] According to Bhante Sujato, modern scholars such as Hellmuth Hecker and Bhikkhu Bodhi "have shown that this story abounds in textual problems, and cannot possibly be a factual account."

According to the one scriptural account of the introduction of the Garudammas (the Gotamī Sutta, Aṅguttara Nikāya 8.51, repeated in the later Cullavagga at X.1), the reason the Buddha gave for his actions was that admission of women to the sangha would weaken it and shorten its lifetime to 500 years. This prophecy occurs only once in the Canon and is the only prophecy involving time in the Canon.[23]

Bodhi notes that, "The fact that the background stories to these rules show them originating at different points in the early history of the Bhikkhuni Sangha casts doubt on the historicity of the present account [in AN 8.51], which shows the eight garudhammas being laid down at the very beginning of the Bhikkhuni Sangha."[24] Bhikkhu Anālayo and Thanissaro Bhikkhu state that garudhammas were initially simply "set out as principles" and did not have the status of a formal training rule until violations occurred.[25][26]

In Young Chung cites Akira Hirakawa in support of the contention "that these rules were appended later,"[27]: 87–88 and concludes,

These 'Eight Rules' are so different in character and tone from the rest of the body of the Bhikṣuṇī Prātimokṣa that I believe they can be disregarded as later additions, appended by the compilers, and not indicative of either the intentions of Gautama Buddha himself, or of the Buddhist traditions as a whole.[27]: 89

In the same paper, however, In Young Chung also noted that cases of Brahmin men and women recorded in the Vinaya treated the bhikkhunīs more harshly using "shaven-headed strumpets or whores", whereas "shaven-headed" was not applied to the bhikkhus in a derogatory manner.[27]: 65

This harsher treatment (which also included rape and assault) of bhikkhunis by society required greater protection. Within these social conditions, Gautama Buddha opened up new horizons for women by founding the bhikkhuni sangha. This social and spiritual advancement for women was ahead of the times and, therefore, drew many objections from men, including bhikkhus. He was probably well aware of the controversy that would be caused by the harassment of his female disciples.[27]: 43

Ian Astley argues that under the conditions of society where there is great discrimination and threat to women living the homeless life, Buddha could not be blamed for the steps he took in trying to secure the Bhikkhuni Sangha from negative attitudes among laity:

In those days (and this still applies to much of present Indian society) a woman who had left the life of the household would otherwise have been regarded more or less as a harlot and subjected to the appropriate harassment. By being formally associated with the monks, the nuns were able to enjoy the benefits of leaving the household life without incurring immediate harm. Whilst it is one thing to abhor, as any civilized person must do, the attitudes and behavior towards women which underlie the necessity for such protection, it is surely misplaced to criticize the Buddha and his community for adopting this particular policy.[27]: 42

Bhikkhu Anālayo goes further, noting that "the situation in ancient India for women who were not protected by a husband would have been rather insecure and rape seems to have been far from uncommon."[28]: 298 According to him the reference to a reduced duration has been misunderstood:

On the assumption that the present passage could have originally implied that women joining the order will be in a precarious situation and their practicing of the holy life might not last long, the reference to a shortening of the lifespan of the Buddha's teaching from a thousand years to five hundred would be a subsequent development.[28]: 299

The Vinaya does not allow for any power-based relationship between the monks and nuns. Dhammananda Bhikkhuni wrote:

Nuns at the time of the Buddha had equal rights and an equal share in everything. In one case, eight robes were offered to both sanghas at a place where there was only one nun and four monks. The Buddha divided the robes in half, giving four to the nun and four to the monks, because the robes were for both sanghas and had to be divided equally however many were in each group. Because the nuns tended to receive fewer invitations to lay-people's homes, the Buddha had all offerings brought to the monastery and equally divided between the two sanghas. He protected the nuns and was fair to both parties. They are subordinate in the sense of being younger sisters and elder brothers, not in the sense of being masters and slaves.[29]

Becoming a bhikkhunī

The progression to ordination as a bhikkhunī is taken in four steps.[30] A layperson initially takes the Ten Precepts, becoming a śrāmaṇerī or novice.[30] They then undergo a two-year period following the vows of a śikṣamāṇā, or probationary nun.[30] This two-year probationary status is not required of monks, and ensures that a candidate for ordination is not pregnant.[30] They then undergo two higher ordinations (upasampada)—first from a quorum of bhikkhunīs, and then again from a quorum of bhikkhus.[30] Vinaya rules are not explicit as to whether this second higher ordination is simply a confirmation of the ordination conducted by the bhikkhunīs, or if monks are given final say in the ordination of bhikkhunīs.[30]

The Fourteen Precepts of the Order of Interbeing

The Order of Interbeing, established in 1964 and associated with the Plum Village movement, has fourteen precepts observed by all monastic and lay members of the Order.[31] They were written by Thích Nhất Hạnh. The Fourteen Precepts (also known as Mindfulness Trainings) of the Order of Interbeing act as bodhisattva vows for bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs of the Plum Village community. They are to help practitioners not to be too rigid in their understanding of the Pratimoksha and to understand the meta-ethics of Buddhism in terms of Right View and compassion.[32]

Plum Village bhikkhunīs recite and live according to the Revised Pratimoksha, a set of 348 rules, based on the Pratimoksha of the Dharmaguptaka school of Buddhism. The Revised Pratimoksha was released in 2003 after years of research and collaboration between monks and nuns of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya tradition. It was devised in order to be able to deal with some corruptions in the Buddhist monastic orders due to traits of modern society which were not present in the time of the Buddha. The Revised Pratimoksha is not based on the Eight Garudhammas, but does retain some of the elements in the Garudhammas which are considered to be useful for the education of nuns. It should, however, be observed that Thich Nhat Hanh has also devised Eight Garudhammas for monks to ensure the mutual respect between monks and nuns, which makes it possible for them to collaborate in the teaching and practice of the Buddhadharma.

In an interview, Chân Không described the Plum Village approach to the Eight Garudhammas:

In Plum Village, nuns do not observe the Eight Garudhammas in their traditional sense, as Nhat Hanh claims they were invented only to help the stepmother of the Buddha. I can accept them just to give joy to the monks who practice in the traditional way. If I can give them joy, I will have a chance to share my insights about women with them, and then they will be unblocked in their understanding.[33]

By tradition

In Tibetan Buddhism

A gelongma (Wylie: dge slong ma) is the Standard Tibetan term for a bhikṣuṇī, a monastic who observes the full set of vows outlined in the vinaya. While the exact number of vows observed varies from one ordination lineage to another, generally the female monastic observes 360 vows while the male monastic observes 265.

A getsulma (Wylie: dge tshul ma) is a śrāmaṇerikā or novice, a preparation monastic level prior to full vows. Novices, both male and female, adhere to twenty-five main vows. A layperson or child monk too young to take the full vows may take the Five Vows called "approaching virtue" (Wylie: dge snyan, THL: genyen). These five vows can be practised as a monastic, where the genyen maintains celibacy, or as a lay practitioner, where the married genyen maintains fidelity.

Starting with the novice ordination, some may choose to take forty years to gradually arrive at the vows of a fully ordained monastic.[34][note 1] Others take the getsulma and gelongma vows on the same day and practice as a gelongma from the beginning, as the getsulma vows are included within the gelongma.

Generally for bhikkhunīs, robes would be maroon with yellow in Tibet.[35]

In Theravada Buddhism

| People of the Pāli Canon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The traditional appearance of Theravada bhikkhunīs is nearly identical to that of male monks, including a shaved head, shaved eyebrows and saffron robes. In some countries, nuns wear dark chocolate robes or sometimes the same colour as monks. The tradition flourished for centuries throughout South and Southeast Asia, but appears to have lapsed in the Theravada tradition of Sri Lanka in the 11th century C.E.[36]: 229 It apparently survived in Burma to about the 13th century, but died out there too.[36]: 229 Although the bhikkhunī order is commonly said to have never been introduced to Thailand, Laos, Cambodia or Tibet, there is substantial historical evidence to the contrary, especially in Thailand.[37][38] With the bhikkhunī lineage extinct, no new bhikkhunīs could be ordained since there were no bhikkhunīs left to give ordination.

For this reason, the leadership of the Theravada bhikkhu Sangha in Burma and Thailand deem fully ordained bhikkhunīs as impossible. "Equal rights for men and women are denied by the Ecclesiastical Council. No woman can be ordained as a Theravada Buddhist nun or bhikkhunī in Thailand. The Council has issued a national warning that any monk who ordains female monks will be punished."[39] Based on the spread of the bhikkhunī lineage to countries like China, Taiwan, Korea, Vietnam, Japan and Sri Lanka, other scholars support ordination of Theravada bhikkhunīs.[40]

Without ordination available to them, women traditionally voluntarily take limited vows to live as renunciants. These women attempt to lead a life following the teachings of the Buddha. They observe 8–10 precepts, but do not follow exactly the same codes as bhikkhunīs. They receive popular recognition for their role. But they are not granted official endorsement or the educational support offered to monks. Some cook while others practise and teach meditation.[41][42][43][44][45]

Robes are orange/yellow for Theravadins in Vietnam, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Laos, Cambodia, and Burma. The colour of robes distinguishes both level of ordination and tradition, with white (usually worn by a male renunciant before ordination) or pink symbolising a state of ambiguity, being on the threshold of a decision, no longer secular and not yet monastic. In Myanmar, Ten-precepts ordained nuns or the Sayalays (there are no fully ordained bhikkhunīs) are usually wearing pink. A key exception to this is in the countries where women are not allowed to wear robes that signify full ordination, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand and (Theravadin in) Vietnam.[35]

White or pink robes are worn by Theravada women renunciants who are not fully ordained. These women are known as dasa sil mata in Sri Lankan Buddhism, thilashin in Burmese Buddhism, Maechi in Thai Buddhism, guruma in Nepal and Laos and siladharas at Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in England.

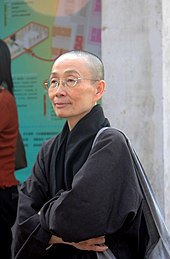

Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, now known as Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, is a Thai scholar who took bhikkhunī ordination in Sri Lanka and returned to Thailand, where bhikkhunī ordination is forbidden and can result in arrest or imprisonment for a woman.[46] She is considered a pioneer by many in Thailand.[47][48]

In 1996, through the efforts of Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women, the Theravada bhikkhunī order was revived when 11 Sri Lankan women received full ordination in Sarnath, India, in a procedure held by Dodangoda Revata Mahāthera and the late Mapalagama Vipulasāra Mahāthera of the Maha Bodhi Society in India with assistance from monks and nuns of the Jogye Order of Korean Seon.[49][50][51]

Theravādin ordination is available for women (as of 2006) in Sri Lanka, where many of the current bhikkhunīs have been ordained. The ordination process has several stages, which can begin with Anagarika (non-ordained) precepts and wearing white robes, but is as far as many women are allowed to take their practice. In Thailand, ordination of women, although legal since 1992, is almost never practiced and nearly all female monastics are known as maechis (also spelled "mae chee"), regardless of their level of attainment.[52]

The first Theravada bhikkhunī ordination in Australia was held in Perth, 22 October 2009, at Bodhinyana Monastery. Four nuns from Dhammasara Nun's Monastery, Ajahn Vayama, Nirodha, Seri and Hasapanna, were ordained as bhikkhunīs in full accordance with the Pali vinaya.

In Mahayana Buddhism

However, the Mahayana tradition in China, Korea, Vietnam, Taiwan and Hong Kong has retained the practice, where female monastics are full bhikṣuṇīs.

In 13th century Japan, Mugai Nyodai became the first female Zen master in that country.[53] Prajñātārā is the twenty-seventh Indian Patriarch of Zen and is believed to have been a woman.[54]

Robes are gray or brown for Mahayana bhikṣuṇīs in Vietnam, gray in Korea; gray or black in China and Taiwan, and black in Japan.[35]

Re-establishing bhikkhunī ordination

To help establish the Bhikshuni Sangha (community of fully ordained nuns) where it does not currently exist has also been declared one of the objectives of Sakyadhita,[55] as expressed at its founding meeting in 1987 in Bodhgaya, India.

The Eight Garudhammas belong to the context of the Vinaya. Bhikkhuni Kusuma writes: "In the Pali, the eight garudhammas appear in the tenth khandhaka of the Cullavagga." However, they are not to be found in the actual ordination process for bhikkhunīs.

The text is not allowed to be studied before ordination. "The traditional custom is that one is only allowed to study the bhikshu or bhikshuni vows after having taken them", Karma Lekshe Tsomo stated during congress while talking about Gender Equality and Human Rights: "It would be helpful if Tibetan nuns could study the bhikshuni vows before the ordination is established. The traditional custom is that one is only allowed to study the bhikshu or bhikshuni vows after having taken them."[56] Ven. Tenzin Palmo is quoted with saying: "To raise the status of Tibetan nuns, it is important not only to re-establish the Mulasarvastivada bhikshuni ordination, but also for the new bhikshunis to ignore the eight garudhammas that have regulated their lower status. These eight, after all, were formulated for the sole purpose of avoiding censure by the lay society. In the modern world, disallowing the re-establishment of the Mulasarvastivada bhikshuni ordination and honoring these eight risk that very censure."[57]

There have been some attempts in recent years to revive the tradition of women in the sangha within Theravada Buddhism in India, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, with many women ordained in Sri Lanka since 1996.[36]: 227 Some of these were carried out with the assistance of nuns from the East Asian tradition;[36]: 227 others were carried out by the Theravada monk's Order alone.[36]: 228 Since 2005, many ordination ceremonies for women have been organised by the head of the Dambulla chapter of the Siyam Nikaya in Sri Lanka.[36]: 228

In Thailand, in 1928, the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand, responding to the attempted ordination of two women, issued an edict that monks must not ordain women as samaneris (novices), sikkhamanas (probationers) or bhikkhunīs. The two women were reportedly arrested and jailed briefly. A 55-year-old Thai Buddhist 8-precept white-robed maechee nun, Varanggana Vanavichayen, became the first woman to receive the going-forth ceremony of a Theravada novice (and the gold robe) in Thailand, in 2002.[58] Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, previously a professor of Buddhist philosophy known as Dr Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, was controversially ordained as first a novice and then a bhikkhuni in Sri Lanka in 2003 upon the revival of the full ordination of women there. Since then, the Thai Senate has reviewed and revoked the secular law banning women's full ordination in Buddhism as unconstitutional for being counter to laws protecting freedom of religion. More than 20 further Thai women have followed in Dhammananda Bhikkhuni's footsteps, with temples, monasteries and meditations centers led by Thai bhikkhunīs emerging in Samut Sakhon, Chiang Mai and Rayong. The stance of the Thai Sangha hierarchy has largely changed from one of denial of the existence of bhikkhunīs to one of acceptance of bhikkhunīs as of foreign (non-Thai) traditions. However Thailand's two main Theravada Buddhist orders, the Mahanikaya and Dhammayutika Nikaya, have yet to officially accept fully ordained women into their ranks. Despite substantial and growing support inside the religious hierarchy, sometimes fierce opposition to the ordination of women within the sangha remains.

In 2010, Ayya Tathaaloka and Bhante Henepola Gunaratana oversaw a dual ordination ceremony at Aranya Bodhi forest refuge in Sonoma County, California where four women became fully ordained nuns in the Theravada tradition.[59]

Bhante Sujato's role

Bhante Sujato, along with his teacher Ajahn Brahm, were involved with re-establishing bhikkhunī ordination in the Forest sangha of Ajahn Chah.[60] Sujato, along with other scholars such as Brahm and Bhikkhu Analayo,[61] had come to the conclusion that there was no valid reason the extinct bhikkhunī order could not be re-established.[62] The ordination ceremony led to Brahm's expulsion from the Thai Forest Lineage of Ajahn Chah. Bhante Sujato, however, was not deterred or intimidated by such a response, and, remaining faithful to his convictions that there was no reason the bhikkhunī order should not be revived, went on to successfully found Santi Forest Monastery, and following Bhante Sujato's wishes, Santi has since flourished as a bhikkhunī monastery vihara since 2012.[60]

International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha

In July 2007 a meeting of Buddhist leaders and scholars of all traditions met at the International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha,[63] in Hamburg, Germany to work toward a worldwide consensus on the re-establishment of bhikkhunīs ordination. 65 delegates, bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs, Vinaya masters and elders from traditional Buddhist countries and Western-trained Buddhologists attended. The Summary Report from the Congress[64] states that all delegates "were in unanimous agreement that Mulasarvastivada bhikshuni ordination should be re-established," and cites the Dalai Lama's full support of bhikkhunī ordination (the Dalai Lama had already demanded the re-establishment of full ordination for nuns in Tibet in 1987).

The aim of the congress has been rated by the organisers of utmost importance for equality and liberation of Buddhist women (nuns). "The re-establishment of nuns’ ordination in Tibet via XIVth Dalai Lama and the international monks and nuns sanghas will lead to further equality and liberation of Buddhist women. This is a congress of historical significance which will give women the possibility to teach Buddha's doctrines worldwide."[65]

In Part Four of Alexander Berzin's Summary Report: Day Three and Final Comments by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama it is said: "But Buddha gave the basic rights equally to both sangha groups. There is no point in discussing whether or not to revive the bhikshuni ordination; the question is merely how to do so properly within the context of the Vinaya."[66]

According to the Summary Report as well as according to the other texts available from the congress there has not been a discussion on how and which of the eight gurudharmas discriminate against Buddhist nuns and how this can be changed in detail in the process of re-establishing the Mulasarvastivada bhikshuni ordination.

Concerns about lineage and legitimacy

The only women's ordination lineage that remains is the Dharmaguptaka one, which is in use in East Asian Buddhism.[67]: 9–10 Nuns from this tradition have assisted in the ordination of nuns in other lineages (e.g. Theravada), where the presence of nuns is a prerequisite for new nuns to be ordained.

This is problematic from a legalist point of view, as a woman from one Buddhist tradition ordained by nuns in another invalidates the notion of lineage and goes against differences in doctrine and monastic discipline among different traditions.[68] Theravada Sanghas like Thailand's refuses to recognize ordinations in the Dharmaguptaka tradition as valid Theravada ordinations and consider impossible to validly re-establish bhikkhunī ordination in lineages where it has ended.[69][70]

However, the German monk Bhikkhu Anālayo, who was a presenter at the International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha,[71] has argued in a number of papers that it is possible for bhikkhus alone to ordain bhikkhunīs if necessary.[70][67]: 23 [72][73] By exploring attitudes towards bhikkhunīs in early Buddhist texts and the story of the foundation of the bhikkhunī order[74] he advocates for the continuing validity of the rule[note 2] allowing "single ordination" (i.e. by monks only) which the Buddha legislated at the birth of the bhikkhunī Sangha:

Mahāpajāpatī then approaches the Buddha to ask how she should proceed in relation to her female followers, whereon the Buddha prescribes that the bhikkhus can perform bhikkhunī ordination [f.n.: Vin II 257,7]

— Bhikkhu Anālayo, The Revival of the Bhikkhunī Order and the Decline of the Sāsana[73]

Later, this rule was followed by another rule[note 3] of "double ordination" requiring the existence of both Sangha to be conducted.

When the problem of interviewing female candidates arises, the Buddha gives another prescription [f.n.: Vin II 271,34] that the bhikkhus can carry out bhikkhunī ordination even if the candidate has not cleared herself—by undergoing the formal interrogation—in front of the bhikkhus, but rather has done so already in the community of bhikkhunīs [...] Thus, as far as the canonical Vinaya is concerned, it seems clear that bhikkhus are permitted to ordain bhikkhunīs in a situation that resembles the situation when the first prescription was given—“I prescribe the giving of the higher ordination of bhikkhunīs by bhikkhus”—that is, when no bhikkhunī order able to confer higher ordination is in existence.

— Bhikkhu Anālayo, The Revival of the Bhikkhunī Order and the Decline of the Sāsana[73]

This is a matter of controversy in the Theravada and Tibetan traditions. He and Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu have had a lengthy exchange of public letters debating the subject, in which Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu opposes:

As I pointed out in OBU [On Ordaining Bhikkhunīs Unilaterally], the general pattern in the Vinaya is that when a rule was altered, the original formulation was automatically rescinded. In special cases where the Buddha meant for both versions to remain valid, for differing situations, he spelled out the situations under which each version was in force. Those are the two general patterns that the Buddha followed throughout the rest of the Vinaya, so those are the patterns to be applied in deciding whether the allowance for unilateral ordination is valid at present. Because the rules for bhikkhunī ordination clearly don't follow the second pattern, we have to assume that the Buddha meant them to be interpreted in line with the first. In other words, when he gave permission in Cv.X.17.2 [the rule of "double ordination"] for bhikkhus to ordain bhikkhunīs after they had been purified in the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha, he automatically rescinded, once and for all, his earlier permission for bhikkhus to ordain bhikkhunīs unilaterally.

And he had good reason for rescinding the earlier permission. If there is no Bhikkhunī Saṅgha to purify the candidate for bhikkhunī ordination, that means there is no Community of bhikkhunīs trained in the apprenticeship lineage established by the Buddha to train the candidate if she were to be ordained. If ordinations such as this were to proceed after the Buddha had passed away, it would result in a bhikkhunī order composed of the untrained leading the untrained.— Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu

He goes on further to argue, among others:

He does not understand the crucial problem in any attempt to revive the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha: that there is no way to provide adequate training for new bhikkhunīs, in that there are no bhikkhunīs with the requisite training that would qualify them to train others. [...] It encourages them to cherry-pick the texts from different traditions, choosing whatever makes immediate sense to them, without having to submit to the training from a bhikkhunī who is truly qualified [...] his false equation of a meticulous attitude toward the rules with an attitude that regards the rules as ends in themselves, and his further false equation of this attitude with the fetter of “dogmatic adherence to rules and observances.” This principle encourages a lack of respect for the rules and for those who follow them. And this would get in the way of learning the many valuable lessons that can come from a willingness to learn from the rules.

— Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu

Bhikkhu Thamma Kittimette, a male member of the Sangha Supreme Council of Thailand, explains that according to custom, a bhikkhunī nun can only be ordained by another bhikkhunī preceptor or teacher who initiates the process. Without a preceptor, a woman cannot be ordained. He says that women circumvent this by claiming to be ordained abroad, but he does not consider those "stealth" ceremonies valid in Thailand.

Recent developments

America

In 1997 Dhamma Cetiya Vihara in Boston[75] was founded by Ven. Gotami of Thailand, then a 10 precept nun. Ven. Gotami received full ordination in 2000, at which time her dwelling became America's first Theravada Buddhist bhikkhunī vihara. Vihara translates as 'monastery' or 'nunnery', and may be both dwelling and community center where one or more bhikkhus or bhikkhunis offer teachings on Buddhist scriptures, conduct traditional ceremonies, teach meditation, offer counseling and other community services, receive alms, and reside. In 2003 Ven. Sudhamma Bhikkhuni took the role of resident female-monk at the Carolina Buddhist Vihara[76] in Greenville, SC (founded by Sri Lankan monks in 2000); her new dwelling thus became the second such community-oriented bhikkhunī vihara in the eastern United States. The first such women's monastic residence in the western United States, Dhammadharini Vihara (now the Dhammadharini Monastery in Penngrove, CA, was founded in Fremont, CA, by Ven. Tathaaloka of the US, in 2005. Soon afterwards, Samadhi Meditation Center[77] in Pinellas Park, Florida, was founded by Ven. Sudarshana Bhikkhuni of Sri Lanka.

Sravasti Abbey, the first Tibetan Buddhist monastery for Western nuns and monks in the U.S., was established in Washington State by Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron in 2003. The Abbey practices in the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya. It is situated on 300 acres forest and meadows, 11 miles (18 km) outside of Newport, Washington, near the Idaho state line. It is open to visitors who want to learn about community life in a Tibetan Buddhist monastic setting. The name Sravasti Abbey was chosen by the Dalai Lama. Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron had suggested the name, as Sravasti was the place in India where comes from the fact that, the Buddha spent 25 Rains Retreats (varsa in Sanskrit and yarne in Tibetan), and communities of both nuns and monks had resided there. This seemed auspicious to ensure the Buddha's teachings would be abundantly available to both male and female monastics at the monastery.[78]

Sravasti Abbey is notable because it is home to a growing group of fully ordained bhikshuni (Buddhist nuns) practising in the Tibetan tradition. This is special because the tradition of full ordination for women was not transmitted from India to Tibet. Ordained women practising in the Tibetan tradition usually hold an ordination that is, in effect, a novice ordination. Venerable Thubten Chodron, while faithfully following the teachings of her Tibetan teachers, has arranged for her students to seek full ordination as bhikshunis in Taiwan.[79]

In January 2014, the Abbey, which then had seven bhikshunis and three novices, formally began its first winter varsa (three-month monastic retreat), which lasted until 13 April 2014. As far as the Abbey knows, this was the first time a Western bhikshuni sangha practising in the Tibetan tradition had done this ritual in the United States and in English. On 19 April 2014 the Abbey held its first kathina ceremony to mark the end of the varsa. Also in 2014 the Abbey held its first Pavarana rite at the end of the varsa.[79][80] In October 2015 the Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering was held at the Abbey for the first time; it was the 21st such gathering.[81]

More recently established Theravada bhikkhunī viharas include: Mahapajapati Monastery[82] where several nuns (bhikkhunīs and novices) live together in the desert of southern California near Joshua Tree, founded by Ven. Gunasari Bhikkhuni of Burma in 2008; Aranya Bodhi Hermitage founded by Ven. Tathaaloka Bhikkhuni in the forest near Jenner, CA, with Ven. Sobhana Bhikkhuni as Prioress, which opened officially in July 2010, where several bhikkhunīs reside together along with trainees and lay supporters; and Sati Saraniya[83] in Ontario, founded by Ven. Medhanandi in appx 2009, where two bhikkhunīs reside. (There are also quiet residences of individual bhikkhunīs where they may receive visitors and give teachings, such as the residence of Ven. Amma Thanasanti Bhikkhuni[84] in 2009–2010 in Colorado Springs; and the Los Angeles residence of Ven. Susila Bhikkhuni; and the residence of Ven. Wimala Bhikkhuni in the mid-west.)

In 2010 the first Tibetan Buddhist nunnery in North America was established in Vermont,[85] called Vajra Dakini Nunnery, offering novice ordination.[85] The abbot of this nunnery is an American woman named Khenmo Drolma who is the first "bhikkhunni," a fully ordained Buddhist nun, in the Drikung Kagyu tradition of Buddhism, having been ordained in Taiwan in 2002.[85] She is also the first westerner, male or female, to be installed as a Buddhist abbot, having been installed as abbot of Vajra Dakini Nunnery in 2004.[86]

Also in 2010, in Northern California, four novice nuns were given the full bhikkhunī ordination in the Thai Theravada tradition, which included the double ordination ceremony. Bhante Gunaratana and other monks and nuns were in attendance. It was the first such ordination ever in the Western hemisphere.[87] The following month, more bhikkhunī ordinations were completed in Southern California, led by Walpola Piyananda and other monks and nuns. The bhikkhunīs ordained in Southern California were Lakshapathiye Samadhi (born in Sri Lanka), Cariyapanna, Susila, Sammasati (all three born in Vietnam), and Uttamanyana (born in Myanmar).

Australia

In 2009 in Australia four women received bhikkhunī ordination as Theravada nuns, the first time such ordination had occurred in Australia.[88] It was performed in Perth, Australia, on 22 October 2009 at Bodhinyana Monastery. Abbess Vayama together with Venerables Nirodha, Seri, and Hasapañña were ordained as bhikkhunīs by a dual Sangha act of Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunīs in full accordance with the Pali Vinaya.[89]

Burma (Myanmar)

The governing council of Burmese Buddhism has ruled that there can be no valid ordination of women in modern times, though some Burmese monks disagree. In 2003, Saccavadi and Gunasari were ordained as bhikkhunīs in Sri Lanka, thus becoming the first female Burmese novices in modern times to receive higher ordination in Sri Lanka.[90][91]

Germany

The International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages took place in Germany, in 18–20 July 2007.

The first bhikkhunī ordination in Germany, the ordination of German nun Samaneri Dhira, occurred on 21 June 2015 at Anenja Vihara.[92]

Indonesia

The first Theravada ordination of bhikkhunīs in Indonesia after more than a thousand years occurred in 2015 at Wisma Kusalayani in Lembang, Bandung.[93] Those ordained included Vajiradevi Sadhika Bhikkhuni from Indonesia, Medha Bhikkhuni from Sri Lanka, Anula Bhikkhuni from Japan, Santasukha Santamana Bhikkhuni from Vietnam, Sukhi Bhikkhuni and Sumangala Bhikkhuni from Malaysia, and Jenti Bhikkhuni from Australia.[93]

Sri Lanka

There have been some attempts to revive the tradition of women in the sangha within Theravada Buddhism in Thailand, India and Sri Lanka, with many women ordained in Sri Lanka since 1996.[36]: 227 In 1996, through the efforts of Sakyadhita, an International Buddhist Women Association, the Theravada bhikkhunī order was revived, when 11 Sri Lankan women received full ordination in Sarnath, India, in a procedure held by Ven. Dodangoda Revata Mahāthera and the late Ven. Mapalagama Vipulasāra Mahāthera of the Mahābodhi Society in India with assistance from monks and nuns of the Korean Chogyo order.[49][51] Some bhikkhunī ordinations were carried out with the assistance of nuns from the East Asian tradition;[36]: 227 others were carried out by the Theravada monk's Order alone.[36]: 228 Since 2005, many ordination ceremonies for women have been organised by the head of the Dambulla chapter of the Siyam Nikaya in Sri Lanka.[36]: 228

Thailand

In 1928, the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand, responding to the attempted ordination of two women, issued an edict that monks must not ordain women as samaneris (novices), sikkhamanas (probationers) or bhikkhunīs. The two women were reportedly arrested and jailed briefly. Varanggana Vanavichayen became the first female monk to be ordained in Thailand in 2002.[58] Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, previously a professor of Buddhist philosophy known as Dr Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, was controversially ordained as first a novice and then a bhikkhunī in Sri Lanka in 2003 upon the revival of the full ordination of women there. Since then, the Thai Senate has reviewed and revoked the secular law banning women's full ordination in Buddhism (enacted 1928) as unconstitutional for being counter to laws protecting freedom of religion. More than 20 further Thai women have followed in Dhammananda Bhikkhuni's footsteps, with temples, monasteries and meditations centers led by Thai bhikkhunīs emerging in Samut Sakhon, Chiang Mai and Rayong. The stance of the Thai Sangha hierarchy has largely changed from one of denial of the existence of bhikkhunīs to one of acceptance of bhikkhunīs as of foreign (non-Thai) traditions. However Thailand's two main Theravada Buddhist orders, the Mahanikaya and Dhammayutika Nikaya, have yet to officially accept fully ordained women into their ranks. Despite substantial and growing support inside the religious hierarchy, sometimes fierce opposition to the ordination of women within the sangha remains.

Tibetan tradition

When Buddhism travelled from India to Tibet, apparently the quorum of twelve fully ordained nuns required for bestowing full ordination never reached Tibet. There are singular accounts of fully ordained Tibetan women, such as the Samding Dorje Phagmo (1422–1455), who was once ranked the highest female master in Tibet, but very little is known about the exact circumstances of their ordination.[94]

The Dalai Lama has authorised followers of the Tibetan tradition to be ordained as nuns in traditions that have such ordination.

According to Thubten Chodron, the current Dalai Lama has said on this issue: "This is the 21st century. Everywhere we are talking about equality....Basically Buddhism needs equality. There are some really minor things to remember as a Buddhist—a bhikshu always goes first, then a bhikshuni....The key thing is the restoration of the bhikshuni vow."[95]

- In 2005, the Dalai Lama repeatedly spoke about the bhikshuni ordination in public gatherings. In Dharamsala, he encouraged, "We need to bring this to a conclusion. We Tibetans alone can't decide this. Rather, it should be decided in collaboration with Buddhists from all over the world. Speaking in general terms, were the Buddha to come to this 21st century world, I feel that most likely, seeing the actual situation in the world now, he might change the rules somewhat...."

- Later, in Zurich during a 2005 conference of Tibetan Buddhist Centers, the Dalai Lama said, "Now I think the time has come; we should start a working group or committee" to meet with monks from other Buddhist traditions. Looking at the German bhikshuni, Ven. Jampa Tsedroen, he instructed, "I prefer that Western Buddhist nuns carry out this work...Go to different places for further research and discuss with senior monks (from various Buddhist countries). I think, first, senior bhikshunis need to correct the monks' way of thinking."

Alexander Berzin referred to the Dalai Lama having said on occasion of the 2007 Hamburg congress

Sometimes in religion there has been an emphasis on male importance. In Buddhism, however, the highest vows, namely the bhikshu and bhikshuni ones, are equal and entail the same rights. This is the case despite the fact that in some ritual areas, due to social custom, bhikshus go first. But Buddha gave the basic rights equally to both sangha groups. There is no point in discussing whether or not to revive the bhikshuni ordination; the question is merely how to do so properly within the context of the Vinaya.[96]

Ogyen Trinley Dorje, one of the two claimants to the title of 17th Karmapa, has announced a plan to restore nuns’ ordination.

No matter how others see it, I feel this is something necessary. To uphold the Buddhist teachings it is necessary to have the fourfold community (fully ordained monks (gelongs), fully ordained nuns (gelongmas), and both male and female lay precept holders). As the Buddha said, the fourfold community are the four pillars of the Buddhist teachings. This is the reason why I'm taking interest in this.

The Tibetan community is taking its own steps to figure out how to approach conferring bhikshuni ordination to women ordained under the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya system. Meanwhile, steps have already been taken to cultivate the bhiksuni monastic community in the West. Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron established Sravasti Abbey in 2003.[97] It is the only Tibetan Buddhist training monastery for Western nuns and monks in the United States. Whilst the Abbey primarily practices under the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, it practices in the Chinese Dharmaguptaka Vinaya lineage. This has allowed the female monastics to take full ordination, travelling to Taiwan to take part in 6–8-week training programmes. In January 2014, the Abbey, which then had seven bhikshunis and three novices, formally began its first winter varsa (three-month monastic retreat), which lasted until 13 April 2014. As far as the Abbey knows, this was the first time a Western bhikshuni sangha practising in the Tibetan tradition had done this ritual in the United States and in English. On 19 April 2014 the Abbey held its first kathina ceremony to mark the end of the varsa. Also in 2014 the Abbey held its first Pavarana rite at the end of the varsa.[80] The Abbey currently has ten fully ordained bhikshunis and five novices.[98]

The official lineage of Tibetan Buddhist bhikkhunīs recommenced on 23 June 2022 in Bhutan when 144 nuns, most of them Butanese, were fully ordained.[99][2]

Vietnam

Chân Không whom initially became a Śikṣamāṇā and months after it became a Bhikkhunī, worked with Thích Nhất Hạnh to promote peace between brothers and sisters during Vietnam war, they traveled to America and Europe to promote Vietnam peace but in 1966 were not allowed to return to Vietnam and became divulgators of Mindfulness and were instrumental in the creation of the Order of Interbeing and Plum Village Monastery in France.[100] In 1963 Thích Quảng Đức and 300 other monks and nuns marched in protest of the war and burned himself as a form of protest for the persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government. In 1967 Bhikkhunī Nhat Chi Mai burned herself as act of protest against the violence of the war.

Triratna Tradition

After 20 years in India, as a Bikkhu, Sangharakshita returned to England and in 1967 began his own Buddhist Order, giving equal ordination to both men and women. Men were called Dharmachari and women, Dharmacharinis. Simply, becoming a committed Buddhist. And whatever lifestyle the 'Order Member' chooses, it is secondary to this commitment.[101][102]

Discrimination against nuns

In March 1993 in Dharamshala, Sylvia Wetzel spoke in front of the Dalai Lama and other influential Buddhists to highlight the sexism of Buddhist practices, imagery and teachings.[103]: 155

Two senior male monastics vocally supported her, reinforcing her points with their own experiences. Ajahn Amaro, a Theravada bhikkhu of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, said, "Seeing the nuns not receiving the respect given to the monks is very painful. It is like having a spear in your heart".[103]: 155 American Tibetan Buddhist monk Thubten Pende gave his views:

When I translated the texts concerning the ordination ceremony I got such a shock. It said that even the most senior nun had to sit behind the most novice monk because, although her ordination was superior, the basis of that ordination, her body, was inferior. I thought, "There it is." I'd heard about this belief but I'd never found evidence of it. I had to recite this text at the ceremony. I was embarrassed to say it and ashamed of the institution I was representing. I wondered, "Why doesn't she get up and leave?" I would.[103]: 154–55

In the foreword of [The First Free Women: Poems of the Early Buddhist Nuns], a collection of original poems by [Matty Weingast], Bhikkuni Anandabodhi writes of her experiences being discriminated against as a nun.[104]

At times it has been a struggle to make my way as a Buddhist nun. Both the support and the modeling that elders can give has been missed. Much of our history and the legacy we receive through the Pali canon can be pretty tough. Nuns are often framed as being a problem, simply by fulfilling our aspiration to give ourselves wholly to the path of awakening. It's challenging when a purehearted intention is met with opposition within the very community to which you belong, just because of your physical form. There were times when the challenges and misunderstandings felt insurmountable. For a while, all of the nuns in the community where I lived were being publicly admonished for not understanding the teachings, for being overly identified with our gender, and for not being sufficiently grateful.[104]: 14

In poetry

The Pāli Canon contains a collection of poems called the Therīgāthā ("Verses of the Elder Nuns")[105] containing verses by nuns from the time of the Buddha's life and some generations following. Also part of the Pāli Canon, the Saṃyutta Nikāya contains a collection of texts called Discourses of the Ancient Nuns.[106]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ For example, the life story of Ven. Geshe Palden Tsering, born in 1934 in Zakok. He took the novice ordination at the age of eight (1942?); in 1973 he took the bhikkshu vows of a fully ordained monk.

- ^ Referred to by Anālayo as "Vin II.257,7" and by Ṭhānissaro as "Cv.X.2.1" (in both cases the first dot is sometime substituted for a whitespace)

- ^ Referred to by Anālayo as "Vin II.271,34" and by Ṭhānissaro as "Cv.X.17.2"

References

- ^ Vicki Mackenzie (22 July 2024). "Making the Sangha Whole". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

- ^ a b DAMCHÖ DIANA FINNEGAN and CAROLA ROLOFF (BHIKṢUṆĪ JAMPA TSEDROEN). "Women Receive Full Ordination in Bhutan For First Time in Modern History", Lion's Roar, JUNE 27, 2022.

- ^ Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu. "Gotamī Sutta [To Gotamī] Aṅguttara Nikāya 8:51". dhammatalks.org.

So he [Ven. Ānanda] said to the Blessed One, "Lord, if a woman were to go forth from the home life into homelessness in the Dhamma & Vinaya made known by the Tathāgata, would she be able to realize the fruit of stream-entry, once-returning, non-returning, or arahantship?"

"Yes, Ānanda, she would...." - ^ "Women in Tibetan Buddhism: Vision of Orgyen Samye Chokhor Ling Nunnery", Pema Mandala, Spring/Summer 2013, p.11

- ^ Alex Gardner, "Yeshe Tsogyal", Treasury of Lives, 2008

- ^ Kusuma, Bhikuni (2000). "Inaccuracies in Buddhist Women's History". In Karma Lekshe Tsomo (ed.). Innovative Buddhist Women: Swimming Against the Stream. Routledge. pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-0-7007-1219-9.

- ^ "A conversation with a sceptic – Bhikkhuni FAQ". Buddhanet. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009.

- ^ Tathaaloka Bhikkhuni. "On the Apparent Non-historicity of the Eight Garudhammas Story As It Stands in the Pali-text Culavagga and Contemporary Vinaya Scholarship" (PDF).

- ^ "Bhikkhunī Pāṭimokkha".

- ^ "Genyen & Rabjung Vows: The Five Root Vows, Rab-jung Vows and Monastic Vows", THEG-CHOG NORBU LING, France, 2023.

- ^ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One), page 352

- ^ Book of the Discipline, Pali Text Society, volume V, Chapter X

- ^ a b Anguttara Nikaya 8.51

- ^ Routledge Encyclopedia of Buddhism, page 822

- ^ Nakamura, Indian Buddhism, Kansai University of Foreign Studies, Hirakata, Japan, 1980, reprinted Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1987, 1989, pages 57–9, point (6)

- ^ Wilson, Liz (2013). Family in Buddhism. SUNY Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-4384-4753-7.

- ^ Harvey, Peter (2000). An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics. Cambridge University Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-521-55640-8.

- ^ Ven. Professor Dhammavihari, Women and the religious order of the Buddha

- ^ Padmanabh S. Jaini (1991). Gender and Salvation Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-06820-3.

this is in contrast to Jain tradition which is always compared to with Buddhism as they emerged almost at the same time, which is non-conclusive in a woman's ability to attain final liberation Digambara makes the opening statement: There is moksa for men only, not for women; #9 The Svetambara answers: There is moksa for women;

- ^ Alice Collett (2006). "BUDDHISM AND GENDER Reframing and Refocusing the Debate". The Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 22 (2): 55–84. doi:10.2979/FSR.2006.22.2.55. S2CID 144745667.

A brief digression into comparative analysis should help to illustrate the significance of these central texts. Although it is possible to ascertain (however, unfortunately from just a few references) that women within the Jain śramaṇa tradition possessed similar freedoms to Buddhist women, Jaina literature leaves to posterity no Therīgāthā equivalent. There are also no extant Jain texts from that period to match stories in the Avadānaśataka of women converts who attained high levels of religious experience. Nor is there any equivalent of the forty Apadānas attributed to the nuns who were the Buddha's close disciples. In Brahminism, again, although Stephanie Jamison has eruditely and insightfully drawn out the vicissitudes of the role of women within the Brahmanic ritual of sacrifice, the literature of Brahmanism does not supply us with voices of women from the ancient world, nor with stories of women who renounced their roles in the domestic sphere in favor of the fervent practice of religious observances.

- ^ a b "Lotus Sutra – Chapter 12". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "The Buddhist Monastic Code II: The Khandhaka Rules Translated and Explained". Archived from the original on 22 November 2005. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Hecker, Hellmuth (2006). "Ananda: The Guardian of the Dhamma". Access to Insight. Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

In the Vinaya (monk's discipline) the Buddha is represented as saying this, but such a prophecy involving time is found only here. There is not other mention anywhere in the whole of the Vinaya (discipline) and the Suttas (discourses). This makes it suspect as an intrusion. The Commentaries, as well as many other later Buddhist writings; have much to say about the decline of the Buddha's Dispensation in five-hundred-year periods, but none of this is the word of the Buddha and only represents the view of later teachers.

- ^ Bodhi, Bhikkhu, ed. (6 October 2012). The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: A Complete Translation of the Anguttara Nikaya. Wisdom Publications. p. 1804. ISBN 978-1-61429-040-7. qtd. in Brasington, Leigh (June 2010). "The Questionable Authenticity of AN 8.51/Cv.X.1: The Founding of the Order of Nuns". Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "On Ordaining Bhikkhunīs Unilaterally | The Question of Bhikkhunī Ordination". www.dhammatalks.org.

- ^ "On the Bhikkhunã Ordination Controversy" (PDF). buddhismuskunde.uni-hamburg.de. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e In Young Chung (1999). "A Buddhist View of Women: A Comparative Study of the Rules for Bhikṣunīs and Bhikṣus Based on the Chinese Pràtimokùa" (PDF). Journal of Buddhist Ethics. 6: 29–105. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ a b Analayo, Bhikkhu (2011). "Mahāpajāpatī's Going Forth in the Madhyama-āgama" (PDF). Journal of Buddhist Ethics. 118. ISSN 1076-9005. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Dhammananda Bhikkhuni (28 December 1999). "The history of the bhikkhuni sangha". Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron. Sravasti Abbey. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Tsomo, Karma Lekshe (2004). "Nuns". MacMillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 1. New York: MacMillan Reference USA. pp. 606–610. ISBN 0-02-865719-5.

- ^ "Order of Interbeing Beginnings - Sister Chan Khong, Learning True Love". 24 December 2005. Archived from the original on 24 December 2005.

- ^ "The Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings". Plum Village. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Alan Senauke; Susan Moon. "Walking in the Direction of Beauty—An Interview with Sister Chan Khong". The Turning Wheel (Winter 1994). Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ Staff. "Venerable Geshe Pal Tsering". Trashi Ganden Choepel Ling Trust. Archived from the original on 3 November 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ a b c "Monastic ordination for women in modern Buddhism". Women Active in Buddhism (WAiB). Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kawanami, Hiroko (2007). The Bhikkhunī Ordination Debate: Global Aspirations, Local Concerns, with special emphasis on the views of the monastic community in Burma, Buddhist Studies Review 24 (2), 227–29

- ^ Tathālokā Bhikkhunī (2015). Glimmers of a Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha. First International Congress on Buddhist Women. Hamburg, Germany.

- ^ Kabilsingh, Chatsumarn (1991). "Two Bhikkhuni Movements in Thailand". Thai Women in Buddhism. Parallax Press. ISBN 978-0-938077-84-8.

- ^ Metthanando Bhikku (7 June 2005). Authoritarianism of the holy kind, buddhistchannel.tv

- ^ "Theravada". Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Thai Forest Tradition (13 September 2009). "Thai Forest Tradition". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "Book Review: Mae Chee Kaew: Her Journey to Spiritual Awakening & Enlightenment". Wandering Dhamma. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "MC Brigitte Schrottenbacher – Meditationteacher Thailand". Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "The Global Peace Initiative of Women". Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Wat Kow Tahm International Meditation Centre, Koh Phangan, Thailand – Mae Chee Ahmon". Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Ordained at Last". Shambala Sun. 2003. Archived from the original on 3 July 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ "Dr Chatsumarn Kabilsingh". UCEC. 8 September 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Why We Need Bhikkhunis as Dhamma Teachers". The Buddhist (TV channel). 5 November 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ a b Bhikkhu Bodhi (11 May 2010). The Revival of Bhikkhuni Ordination in the Theravada Tradition. Dignity and Discipline: Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns. ISBN 978-0-86171-588-6.

- ^ Kusuma Devendra. "Abstract: Theravada Bhikkhunis". International Congress On Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ a b Dhammananda Bhikkhuni (1 May 2012). "Keeping track of the revival of bhikkhuni ordination in Sri Lanka". Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ "The Ordination Process". Bhavana Society. Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ^ "Abbess Nyodai's 700th Memorial". Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Austin, Shoshan Victoria (2012). "The True Human Body". In Carney, Eido Frances (ed.). Receiving the Marrow. Temple Ground Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-9855651-0-7.

- ^ "Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "A Summary Report of the 2007 International Congress on the Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages, Part 2". Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "A Summary Report of the 2007 International Congress on the Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages, Part 3". Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ a b Sommer, PhD, Jeanne Matthew. "Socially Engaged Buddhism in Thailand: Ordination of Thai Women Monks". Warren Wilson College. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Another Step Forward". Lion's Roar. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ a b Thanissara; Cintamani; Jitindriya (25 August 2010). "The Time Has Come". Lion's Roar. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Analayo, Bhikkhu (2013). "The Revival of the Bhikkhunī Order and the Decline of the Sāsana" (PDF). The Journal of Buddhist Ethics. 20. ISSN 1076-9005.

- ^ Sujato, Ajahn. "Bhikkhuni Ordination". Buddhist Society of Western Australia. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ "Background and Objectives". International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha. 20 July 2007. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ "A Summary Report of the 2007 International Congress on the Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages, Part 1". Study Buddhism. August 2007. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "Press release 09/06/2006". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "A Summary Report of the 2007 International Congress on the Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages, Part 4". Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ a b Anālayo (2017). "The Validity of bhikkhunī Ordination by bhikkhus Only" (PDF). JOCBS. 12: 9–25.

- ^ Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2020). The Question of Bhikkhuni Ordination. Valley Center, CA: Metta Forest Monastery.

- ^ "ประกาศห้ามพระเณรไม่ให้บวชหญิงเป็นบรรพชิต ลงวันที่ ๑๘ มิถุนายน ๒๔๗๑." (ม.ป.ป.). [ออนไลน์]. เข้าถึงได้จาก: <ลิงก์ Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine>. (เข้าถึงเมื่อ: ๒๓ พฤศจิกายน ๒๕๕๔).

- ^ a b Talbot, Mary. "Bhikkhuni Ordination: Buddhism's Glass Ceiling". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Abstract: The Four Assemblies and the Foundation of the Order of Nuns, Foundation for Buddhist Studies, University of Hamburg, archived from the original on 18 November 2018, retrieved 18 November 2018;"Women's Renunciation in Early Buddhism – The Four Assemblies and the Foundation of the Order of Nuns", Dignity & Discipline, The Evolving Role of Women in Buddhism, Wisdom Publications, 2010, pp. 65–97

- ^ Analayo, Bhikkhu. "On the Bhikkhunã Ordination Controversy" (PDF). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Analayo, Bhikkhu. "The Revival of the Bhikkhunī Order and the Decline of the Sāsana" (PDF). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "about: core faculty & members". Āgama research group. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Dhamma Cetiya Vihara in Boston". Archived from the original on 18 November 2013.

- ^ "Carolina Buddhist Vihara". Carolina Buddhist Vihara.

- ^ "Samadhi Meditation Center". Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Dalai Lama Endorsement – Sravasti Abbey – A Buddhist Monastery". Sravasti Abbey. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Abbey Training – Sravasti Abbey – A Buddhist Monastery". Sravasti Abbey. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Living in Vinaya – Sravasti Abbey – A Buddhist Monastery". Sravasti Abbey. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ ""Joys and Challenges" Are the Focus for 21st Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering – Sravasti Abbey – A Buddhist Monastery". Sravasti Abbey. 4 December 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "Mahapajapati Foundation". 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Sati Saraniya Hermitage – Buddhist Women on a Path of Spiritual Awakening".

- ^ "Dharma Seed – Amma Thanasanti's Dharma Talks". www.dharmaseed.org.

- ^ a b c "Home". Vajra Dakini Nunnery.

- ^ "Women Making History". Archived from the original on 1 June 2010.

- ^ Boorstein, Sylvia (25 May 2011). "Ordination of Bhikkhunis in the Theravada Tradition". HuffPost.

- ^ "Thai monks oppose West Australian ordination of Buddhist nuns". Wa.buddhistcouncil.org.au. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Bhikkhuni Ordination". Dhammasara.org.au. 22 October 2009. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Saccavadi's story". Sujato's Blog. 16 February 2010.

- ^ Toomey, Christine (Spring 2016). "The Story of One Burmese Nun". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

- ^ Bhikkhuni Happenings – Alliance for Bhikkhunis. Bhikkhuni.net. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ a b "First Theravada Ordination of Bhikkhunis in Indonesia After a Thousand Years" (PDF). bhikkhuni.net. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Haas, Michaela. Dakini Power: Twelve Extraordinary Women Shaping the Transmission of Tibetan Buddhism in the West. Shambhala Publications, 2013. ISBN 1559394072. p. 6.

- ^ "A New Possibility: Introducing Full Ordination for Women into the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Summary of Speeches at the Bhikshuni Congress: Day 3. 2007 International Congress on the Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages. Alexander Berzin Archives. University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany. July 2007.

- ^ "Home – Sravasti Abbey – A Buddhist Monastery". Sravasti Abbey. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "Our Community – Sravasti Abbey – A Buddhist Monastery". Sravasti Abbey. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Mackenzie, Vicki (22 July 2024). "Making the Sangha Whole". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

- ^ "Sister Chan Khong". Plum Village Monastery. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ George D. Chryssides & Margaret Z. Wilkins (2006). A Reader in New Religious Movements: Readings in the Study of New Religions. Continuum International Publishing Group, London.

- ^ Stephen Batchelor (1994). Parallax Press (ed.). The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, p.133.

- ^ a b c Mackenzie, Vicki (1999). Cave in the Snow: A Western Woman's Quest for Enlightenment. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-4389-5.

- ^ a b Weingast, Matty (2020). The First Free Women: Poems of the Early Buddhist Nuns. Shambhala. ISBN 9781611807769.

- ^ "Therigatha: Verses of the Elder Nuns". Access to Insight. Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. 30 November 2013.

- ^ "Discourses of the Ancient Nuns: (Bhikkhuni-samyutta)", translated from the Pali by Bhikkhu Bodhi". Access to Insight. Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. 30 November 2013.

General bibliography

- Hirakawa, Akira (1999). Monastic Discipline for the Buddhist Nuns: An English Translation of the Chinese Text of the Mahāsāṃghika-Bhikṣuṇī-Vinaya. Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute.

- Hüsken, Ute (2000), "The Legend of the Establishment of the Buddhist Order of Nuns in the Theravada Vinaya Pitaka" (PDF), Journal of the Pali Text Society, XXVI: 43–70, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2015

- Rongxi, Li; Dalia, Albert A. (2002). The Lives of Great Monks and Nuns, Berkeley CA: Numata Center for Translation and Research (T2063: Biographies of Buddhist Nuns)

- Tsomo, Karma Lekshe (1 April 1999). Buddhist Women Across Cultures: Realizations. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4138-1.