Bhaktāmara Stotra

| Bhaktāmara Stotra | |

|---|---|

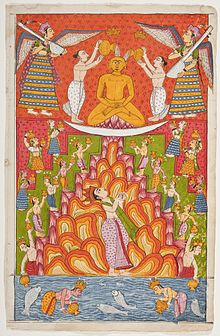

Illustration of Rishabhanatha in a manuscript of Bhaktāmara Stotra | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Jainism |

| Author | Acharya Manatunga |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Period | 7th century CE |

| Verses | 48 (originally 52) Verses as per the Digambara Sect and 44 Verses (Originally as per ancient scriptures) as per the Shwetambara Sect |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

The Bhaktāmara Stotra (Sanskrit: भक्तामरस्तोत्र, romanized: bhaktāmara-stotra, lit. 'Hymn of an immortal devotee') is a Jain religious hymn (stotra) written in Sanskrit. It was authored by Manatunga (7th century CE).[1] The Digambaras believe it has 48 verses while Śvetāmbaras believe it consists of 44 verses.[2]

The hymn praises Rishabhanatha, the first Tirthankara of Jainism in this time cycle.

Authorship

Bhaktāmara Stotra was composed by Manatunga in 6th century CE.[3] Digambara legends associate Manatunga with a ruler named Mihira Bhoja. However, Manatunga probably lived a few centuries before Bhoja. He is identified by some scholars as Kshapanaka, one of the Navaratnas in the court of legendary Vikramaditya. An unidentified Sanskrit poet Matanga, composer of Brahaddeśī on music theory, may also have been the same person.

Bhaktāmara Stotra was composed sometime in the Gupta or the post-Gupta period, making Manatunga approximately contemporary with other navaratnas like Kalidasa and Varahamihira. Several spots near Bhopal and Dhar are traditionally associated with Manatunga.[citation needed]

There are several legends presented by different Śvetāmbara monks. The most popular is the one depicted in Prabandha Cintamani written by Acharya Merutungasuri in 1305 AD. According to the legend, two scholars Bana Pandit and Mayura Pandit were members of king Bhoja's court. It is said that they made supra-human things possible by their mantric powers. To illustrate the statement, two examples are provided. Mayura Pandit worshipped the Sun God with a hymn he composed known as Surya Sataka. He got cured of leprosy that he was suffering from as a result of his sister's curse. He was blessed by Sun God when he composed the 6th verse. Envying him, Bana Pandit got his hands and legs chopped off and took it as a challenge to make Goddess Chandi bless him in 6 letters. He then composed Candi Sataka and his limbs regrew before he even recited the 6th letter. The king was pleased by both of them. Thereafter, the courtiers told the king that Śvetāmbara Jain Acharyas did not possess such mantric powers and that they must be banished from the kingdom. At that time, Acharya Manatungsuri was preaching Jainism in the region. He was called to the king's court and was challenged to prove the greatness of Tirthankaras or leave the kingdom otherwise. Acharya Manatungsuri replied "our Lord, free from love and hatred as He is, does not perform miracles. However, his attendant demigods do." Thereafter, Manatungsuri got himself fettered in 44 chains and stood behind a jinaalay (Jain Temple) facing its rear side. He then composed the Bhaktamara Stotra and with every verse he composed, one fetter got cut off. By the time he completed all 44 verses, the temple turned around to face Acharya Manatungsuri. He stood face to face with the temple, with all the fetters cut off. This extraordinary spectacle established the mantric powers Śvetāmbara monks possessed. This account has been described in great detail in Acharya Merutungasuri's Prabandh Cintamani. [4][5]

According to a Digambara legend, Manatunga composed this hymn while chained and imprisoned by king Bhoja. As he completed each verse, he was getting closer to liberation, such as the chain breaking or the prison door miraculously opening. Manatunga was free when all the verses were finished.[citation needed]

The hymn is recognised by both Digambara and Śvetāmbara sects of Jainism. The Digambaras recite 48 verses, while the Śvetāmbaras recite 44 verses. The latter believe 4 verses (verse 32, 33, 34, and 35 as in the 48-verse version) were added later and were called the interpolated verses.[6] It is known that they do not dismiss reciting them. However, Śvetāmbaras believe that Manatungasuri composed only 44 verses and the rest of them were interpolated later. Therefore, Śvetāmbaras include them in the appendix.[2]

The oldest surviving palm leaf manuscript (dated 1332 AD) that illustrates this stotra is found at the Patan Library.[2] It only consists of 44 verses as believed by the Śvetāmbara Murtipujaks. Some scholars believe that it originally had 44 verses based on the fact that the Śvetāmbara sect always had more saints and scholars than their Digambara counterparts and that there is a greater probability of them having preserved the correct version.

Structure

Bhaktāmara Stotra has 44 stanzas (Śvetāmbara belief) or 48 stanzas (Digambara belief). Every stanza has four parts. Every part has 14 letters. The complete panegyric is formed by 2464 (Śvetāmbara belief) or 2688 (Digambara belief) letters.

The Bhaktāmara Stotra is composed in the meter vasantatilaka. All the fourteen syllables of this meter are equally divided between short and long syllables i.e. seven laghu and seven gurus and this belongs to sakvari group of meters.[7]

Bhaktāmara Stotra is recited as a stotra (prayer) or sung as a hymn, somewhat interchangeably.

Influence

Bhaktāmara Stotra has influenced other Jain prayers, such as the Kalyānamandira Stotra, devoted to the twenty-third tirthankara, and the Svayambhu Stotra, devoted to all the twenty-four Tirthankaras. Additional verses here praise the omniscience of Adinatha.[8][9]

Bhaktāmara Stotra is widely illustrated in paintings.[10][11] A 1332 AD palm leaf manuscript of the stotra illustrating only the 44 verses (as believed by Śvetāmbaras) is well-preserved at the Patan library. It is considered to be the oldest surviving manuscript.[2]

At the Sanghiji temple at Sanganer, there is a panel illustrating each verse. There is a temple at Bharuch with a section dedicated to the Bhaktāmara Stotra and its author Manatunga.[12]

Devotees believe that the verses of Bhaktāmara Stotra possess magical properties, and associate a mystical diagram (yantra) with each verse.

Modern translations

An English translation was published by Vijay K. Jain in 2023.[13]

References

- ^ Jain 2012, p. xi.

- ^ a b c d Rājayaśasūrīśvara (1996). Bhaktamara Darshan (in Gujarati). Śrī Jaina Dharma Phaṇḍa Pheḍhī.

- ^ Orsini & Schofield 1981, p. 88.

- ^ Divine Mystical Jain Yantra Mantra Stotra (in Sanskrit). Harshadray Heritage. 2004.

- ^ "Book Detail – Jain eLibrary". Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Jackson, Abraham Valentine Williams (1917). Indo-Iranian Series.

- ^ Bhaktamar Stotra: The Song of Salvation, ISBN 9788190082396

- ^ The A to Z of Jainism, ISBN 0810868210

- ^ Svayambhu Stotra: Adoration of the Twenty-four Tirthankara, ISBN 8190363972

- ^ "Bhaktamar Mantras". Archived from the original on 24 January 2001. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- ^ "Sumant Shah series of paintings". Greatindianarts.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007.

- ^ Shri Bharuch Teerth Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jain 2023.

Further reading

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363945

- Jain, Vijay K. (2023). Ācārya Mānatunga’s Bhaktāmara Stotra आचार्य मानतुंग विरचित भक्तामर स्तोत्र. Dehradun: Vikalp Printers. ISBN 978-93-5906-111-5.

- Orsini, Francesca; Schofield, Katherine Butler, eds. (1981), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India, Open Book Publishers, ISBN 978-1-78374-105-2