Bandura

| |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.321 |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

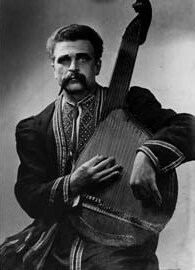

A bandura (Ukrainian: бандура [bɐnˈdurɐ] ⓘ) is a Ukrainian plucked-string folk-instrument. It combines elements of the zither and lute and, up until the 1940s, was also often called a kobza. Early instruments (c. 1700) had 5 to 12 strings and resembled lutes. In the 20th century, the number of strings increased initially to 31 strings (1926), then to 56 strings – 68 strings on modern "concert" instruments (1954).[2]

Musicians who play the bandura are referred to as bandurists. In the 19th and early 20th centuries traditional bandura players, often blind, were called kobzars.[3] It is suggested that the instrument developed as a hybrid of gusli (Eastern-European psaltery) and kobza (Eastern-European lute).[citation needed] Some also consider the kobza as a type or an instrument resembling the bandura.[4] The term bandura occurs in Polish chronicles from 1441. The hybridization, however, occurred in the late-18th or early-19th centuries.

Etymology and terminology

Banduras are first recorded in a Polish chronicle of 1441,[5] which mentioned that Sigismund III, king of Poland,[6] employed the Ruthenian Taraszko at court to play the bandura and be his chess companion. Medieval Polish manuscripts recorded other court bandurists of Ukrainian descent.[5]

The term bandura is generally thought to have entered the Ukrainian language via Polish, either from Latin or from the Greek pandora or pandura; some scholars believe the term was introduced directly from Greek.

The use of the term bandore (or bandora) stems from a now discredited assumption, initially made by Russian musicologist A. Famintsyn, that the word was borrowed directly from England. The word appeared in early 20th century Soviet Ukrainian-English and Russian-English dictionaries. Eastern European string instruments such as the hurdy-gurdy are occasionally referred to as banduras, and the five-string guitar as a bandurka.

History

The use of lute-like stringed instruments by Ukrainians dates back to 591. In that year, Byzantine Greek chronicles mention Bulgar warriors who travelled with lute-like instruments they called kitharas. There are iconographic depictions of lute-like instruments in the 11th-century frescoes of Saint Sophia's Cathedral, the capital of the Kievan Rus'. It is not known by what specific term these instruments were referred to in those early times, although it has been surmised that the lute-like instrument was referred to by the generic medieval Slavic term for a string instrument—"husli".

Early years

Up until the mid 18th century, the instrument known as the bandura had frets and was played in a manner similar to the lute or guitar. The instrument was similar to the German bandore with usually 5 single courses strung along the neck. In the mid 18th century additional strings known as "prystrunky" began to appear. Gradually the zither–like bandura replaced the lute–like bandura by the middle of the 19th century.

The invention of an instrument combining organological elements of lute and psaltery is sometimes credited to Francesco Landini, an Italian lutenist-composer during the trecento. Filippo Villani writes in his Liber de civitatis Florentiae, "...[Landini] invented a new sort of instrument, a cross between lute and psaltery, which he called the serena serenarum, an instrument that produces an exquisite sound when its strings are struck." Rare iconographic evidence (by artists such as Alessandro Magnasco) reveals that such instruments were still in use in Italy ca. 1700.

In the Hetman state in left-bank Ukraine, the bandura underwent significant transformations with the development of a professional class of itinerant blind musicians called kobzars. The first mentions of an institution for the study of bandura playing date back to 1738, to a music academy in Hlukhiv where the bandura and violin were taught to be played from sheet music. This was the first music school in Eastern Europe and prepared musicians and singers for the Tsarist Court in St Petersburg.

The construction and playing technique were adapted to accommodate its primary role as accompaniment to the solo singing voice. By the mid 18th century, the instrument had developed into a form with approximately four to six stoppable strings strung along the neck (with or without frets) (tuned in 4ths) and up to sixteen treble strings, known as prystrunky, strung in a diatonic scale across the soundboard. The bandura existed in this form relatively unchanged until the early 20th century.

Court years

Up until the 20th century, the bandura repertoire was an oral tradition based primarily on vocal works sung to the accompaniment of the bandura. These included folk songs, chants, psalms, and epics known as dumy. Some folk dance tunes were also part of the repertoire.

The instrument became popular in the courts of the nobility in Eastern Europe. There are numerous citations mentioning the existence of Ukrainian bandurists in both Russia and Poland. Empress Elisabeth of Russia (the daughter of Peter the Great) had a long-standing relationship and maybe a morganatic marriage with her Ukrainian court bandurist, Olexii Rozumovsky.[7]

In 1908, the Mykola Lysenko Institute of Music and Drama in Kyiv began offering classes in bandura playing, instructed by kobzar Ivan Kuchuhura Kucherenko. Kucherenko taught briefly until 1911, and attempts were made to reopen the classes in 1912 with Hnat Khotkevych; however, the death of Mykola Lysenko and Khotkevych's subsequent exile in 1912 prevented this from happening. Khotkevych published the first primer for the bandura in Lviv in 1909. It was followed by a number of other primers specifically written for the instrument, most notably those by Mykhailo Domontovych, Vasyl Shevchenko and Vasyl Ovchynnikov, published in 1913–14.

In 1910, the first composition for the bandura was published in Kyiv by Khotkevych. It was a dance piece entitled "Odarochka" for the folk bandura played in the Kharkiv style. Khotkevych prepared a book of pieces in 1912 but, because of the arrest of the publisher, it was never printed. Despite numerous compositions being written for the instrument in the late 1920s and early 30s, and the preparation of these works for publication, little music for the instrument was published in Ukraine. A number of bandura primers appeared in print in 1913–14, written by Domontovych, Shevchenko, and Ovchynnikov and containing arrangements of Ukrainian folk songs with bandura accompaniment.

Years of suppression

Tsarist sanctions

The persecution of Kobzars started in 1876 under Imperial Russia with the publication of the Ems Ukaz: stage performances by kobzars and bandurists were officially banned. Paragraph 4 of the decree was specifically aimed at preventing all music, including ethnographic performances in Ukrainian. As a result, blind professional musicians such as the kobzars turned to the street for their sustenance. In the major Russian speaking cities, they were often treated like common street beggars by the non-Ukrainian population, being arrested and having their instruments destroyed. The restrictions and brutal persecution were only halted in 1902 after a special delegation was sent to the Ministry of Internal Affairs from the Imperial Archaeological Society.

Sanctions introduced by the Russian government in 1876 (Ems ukaz) that severely restricted the use of Ukrainian language and in point 4, also restricted the use of the bandura on the concert stage since all of the repertoire was sung in Ukrainian. Many bandurists and kobzars were systematically persecuted by the authorities controlling Ukraine at various times. This was because of the association of the bandura with specific aspects of Ukrainian history, and also the prevalence of religious elements in the kobzar repertoire that eventually was adopted by the latter-day bandurists. Much of the unique repertoire of the kobzars idealized the legacy of the Ukrainian Cossacks. A significant section of the repertoire consisted of para-liturgical chants (kanty) and psalms sung by the kobzari outside of churches as the latter were often suspicious of, and sometimes hostile to, the kobzars' moral authority.

Because of these restrictions and the rapid disappearance of kobzars and bandurists, the topic of the minstrel art of the itinerant blind bandura players was again brought up for discussion at the XIIth Archeological Conference held in Kharkiv in 1902. It was believed that the last blind kobzar, (Ostap Veresai) had died in 1890; however, upon investigation, six blind traditional kobzars were found to be alive and performed on stage at the conference. Thereafter, the rise in Ukrainian self-awareness popularized the bandura, particularly among young students and intellectuals. Gut strings were replaced by metal strings, which became the standard after 1902. The number of strings and size of the instrument also began to grow, in order to accommodate both the sound production required for stage performances, and the performance of a new repertoire of urban, folkloric song which required more sophisticated accompaniment.

Use of the instrument fell into decline amongst the nobility with the introduction of Western musical instruments and Western music fashions, but it remained a popular instrument of the Ukrainian Cossacks in the Hetmanate. After the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich, the instrument continued to be played by wandering, blind musicians known as kobzari in Right-bank Ukraine. With the growing appreciation of bandurist capellas as an art form came the accelerated development of technology related to the performance on the bandura. At the beginning of the 20th century the instrument was thought to have gone into total disuse. At that time it had some 20 strings with wooden pegs (4 basses and 16 prystrunky). The volume obtained from the instrument was not loud enough for the concert stage.

Period of tolerance

In 1918–20 a number of bandurists were shot by Bolsheviks after the October Revolution, during the Russian Civil War. Most of these bandurists were members of the various Ukrainian Armed forces or played for Ukrainian soldiers. Current accounts list some 20 known bandurists who perished in this time period. Few kobzari are included in this list. Few records accurately document the deaths of bandurists from this period.

From 1923, there was a period of tolerance to Ukrainian language and culture existed whilst Soviet power was entrenched in the country. During this time the popularity of the bandura grew considerably.

The bandura underwent significant changes in the 20th century, in construction, technique and repertoire. Initial developments were made in making the range of the instrument greater and improving the sonority of the instrument. By 1911 instruments with 32 diatonically tuned strings had become common, almost replacing the traditional instruments played by the traditional kobzars. Metal tuning pegs made an appearance around 1914. This allowed the performer to tune his instrument accurately. This was crucial particularly when playing in an ensemble. By the mid-1920s, chromatic strings were also added to the instrument which allowed the performer to play accidentals and allowed the performer to modulate into close related keys. The construction of the instrument was modified to allow for the additional tension of these strings. The number of strings rose to about 56.

Subsequent developments included metal strings (introduced post-1891) and metal tuning pegs (introduced in 1912), additional chromatic strings (introduced from 1925) and a mechanical lever system for rapid re-tuning of the instrument (first introduced in 1931). In 1931 the first mechanisms were developed, which allowed the bandurist to retune his instrument quickly in a variety of more distinct keys.

In 1926, a collection of bandura compositions compiled by Mykhailo Teliha was published in Prague. Hnat Khotkevych also prepared a number of collections of pieces for the bandura in 1928; however, because of dramatic political changes within the Soviet Union, none of these collections was published.

Although workshops for the serial manufacture of banduras had been established earlier outside of Ukraine (in Moscow (1908), and Prague (1924)), continuous serial manufacture of banduras was only started in Ukraine, sometime in 1930.

Formal conservatory courses in bandura playing were re-established only after the Soviet revolution, when Khotkevych returned to Kharkiv and was invited to teach a class of bandura playing at the Muz-Dram Institute in 1926 and in Kyiv in 1938. Vasyl Yemetz established in 1923, a bandura school in Prague, with over 60 students. By 1932–33, however, the Soviets tried to control the rise of Ukrainian self-awareness with severe restrictions on Ukrainian urban folk culture. Bandura classes in Ukraine were disbanded, and many bandurists were repressed by the Soviet government.

Years of persecution

In 1926, the Communist Party of Soviet Union (bolsheviks) began to fight against presumed nationalist tendencies within the local Communist parties. In 1927, the Central Committee decreed that Russian was a special language within the Soviet Union. By 1928, restrictions came into force that directly affected the lifestyle of the traditional kobzars, and stopped them from traveling without a passport and performing without a license. Restrictions were also placed on accommodations that were not registered and also on the manufacturing or making of banduras without a license.

In July, 1929, many Ukrainian intellectuals were arrested for being supposed members of the (very likely fictional) Union for the Liberation of Ukraine. A number of prominent bandurists disappeared at about this time. Most of these bandurists had taken part in the Revolution of 1918 on the side of the Ukrainian National Republic. With the prosecution of the members of the organization for the Liberation of Ukraine, a number of bandurists and also people who had helped organize bandura ensembles were included. Some were arrested and sent to camps in Siberia. Others were sent to dig the White Sea Canal. Some bandurists were able to escape from these camps. In the 1930s, there was also a wave of arrests of bandurists in the Kuban. Many of these arrested bandurists received relatively "light" sentences of 5–10 years camp detentions or exile, usually in Siberia.

In the 1930s, the authentic kobzar tradition of wandering musicians in Ukraine came to an end. In this period, documents attest to the fact that a large number of non-blind bandurists were also arrested at this time, however they received relatively light sentences of 2–5 years in penal colonies or exile.

In January 1934, the Ukrainian government decreed that the capital of the republic would move to Kyiv. As all government departments were moved, many government organizations did not work correctly or efficiently for significant periods of time. In the move, many important documents were lost and misplaced. From January, the artists of the state funded Bandurist Capellas stopped being paid for their work. By October, without receiving any pay, the state funded Bandurist Capellas stopped functioning. In December, a wave of repressions against Ukrainian intellectuals also resulted in 65 Ukrainian writers being arrested.

In the 1930s, Soviet authorities implemented measures to control and curtail aspects of Ukrainian culture (see Russification) they deemed unsuitable. This also included any interest in the bandura.[8] Various sanctions were introduced to control cultural activities that were deemed anti-Soviet. When these sanctions proved to have little effect on the growth in interest in such cultural artifacts, the carriers of these artefacts, such as bandurists, often came under harsh persecution from the Soviet authorities. Many were arrested and some executed or sent to labor camps. At the height of the Great Purge in the late 1930s, the official State Bandurist Capella in Kyiv was changing artistic directors every 2 weeks because of these political arrests.

Throughout the 1930s, bandurists were constantly being arrested and taken off for questioning which may have lasted some months. Many were constantly harassed by the authorities. While until around 1934 those incriminated received relatively light sentences of 2–5 years, after 1936, the sentences were often fatal and immediate – death by shooting. In 1937–38, large numbers of bandurists were executed. Documents have survived of the many individual executions of bandurists and kobzars of this period. So far, the documentation of 41 bandurists sentenced to be shot have been found with documents attesting to approximately 100 receiving sentences of between 10–17 years. Often, those who were arrested were tortured to obtain a confession. Sentences were pronounced by a Troika and were dealt out swiftly within hours or days of the hearing. The families of those who were executed were often told that the bandurist had been sent to a camp without the right to correspond.

Mass murder

In recent years evidence of this has emerged, pointing to an event (often masked as an ethnographic conference) that was held in Kharkiv, the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, in December 1933 – January 1934. Many itinerant street musicians from all over the country, specifically blind kobzars and lirnyks, were invited to attend, amounting to an estimated 300 participants. All were subsequently executed as unwanted elements in the new Soviet Society.

In 1978, evidence came to light (Solomon Volkov's Testimony: The Memoirs of Shostakovych and Leonid Plyushch's History's Carnival) (1978) about the mass murder of the Ukrainian blind musicians by the Soviet authorities. Previous mentions of such a tragedy date back to 1981 in the writings of dissident Ukrainian poet Mykola Horbach.

According to a widespread version, the musicians were gathered under the guise of an ethnographic conference and then mass-executed. Various versions give different times for the conference and location. The confusion is exacerbated by the fact that little differentiation is made between the kobzari, bandurists and lirnyky. Archival documents attesting to the organisation of such a conference have been found which were affirmed by bandurist Mykhailo Polotay who had been one of the instigators and organisers of the conference. Although no documents directly attesting to the mass-execution of the kobzari has been found to date, we do have a significant list of kobzari and bandurists who died or disappeared at this time.

By one of the versions, the conference was organized near Kharkiv in December 1933, where 300 (c.50) blind kobzars and (c.250) lirnyks were gathered near Kharkiv and left to die of exposure in a gully outside of the city limits. The location of this atrocity has recently been discovered on the territory of recreation building owned by the KGB (or the NKVD) in the area of Piatykhatky, Kharkiv Oblast. A monument has also been erected in the centre of Kharkiv to mark this tragic event.

Years of stagnation

After World War II, and particularly after the death of Joseph Stalin, these restrictions were somewhat relaxed and bandura courses were again re-established in music schools and conservatories in Ukraine, initially at the Kyiv conservatory under the direction of Khotkevych's student Volodymyr Kabachok, who had returned to Kyiv after being released from a gulag labour camp in Kolyma.

After the death of Stalin, the draconian policies of the Soviet administration were halted. Many bandurists who, during that period, had been persecuted were "rehabilitated". Some of those exiled returned to Ukraine. Conservatory courses were re-established and, in time, the serial manufacture of banduras was rekindled by musical instrument factories in Chernihiv and Lviv.

Most accounts of Nazi persecution of kobzars and bandurists were Soviet fabrications, however a number of prominent bandurists did die at the hands of the Nazis. One notable bandurist was Teliha who was executed in the tragic Babi Yar massacre in Kyiv in February 1942. Soviet sources tried attribute the deaths of numerous kobzars such as I. Kucherenko to the German-Nazi occupation. Recent documents have disproved most of these versions of their deaths.

In the 1950s, a number of bandurists also either died or disappeared under strange and unexplained circumstances. Some had accidents (Singalevych, Kukhta, Konyk). A significant number, approximately 30–50 bandurists, were also deported to Siberia from Western Ukraine. By the 1960s, total Communist Party control of the bandura art was achieved. A period of feminisation of the bandura took place where males were not accepted into conservatory courses to study the bandura. The repertoire of those that played the bandura underwent a major change from history songs and epics to romantic love and lyric works and transcriptions of classical piano works.

After World War II, two factories dominated the manufacturing of banduras: the Chernihiv Musical Instrument Factory (which produced 120 instruments a month, over 30,000 instruments from 1954 to 1991) and the Trembita Musical Instrument Factory in Lviv (which has produced over 3,000 instruments since 1964). Other serially manufactured instruments were also made in workshops in Kyiv and Melnytso-Podilsk.

In Germany in 1948, the Honcharenko brothers in the workshops of the Ukrainian Bandurist Chorus continued to refine the mechanism to make it more reliable for the concert stage and also even out the tone of the instrument. Similar developments were also undertaken by Ivan Skliar in Ukraine who in 1956 developed the concert Kyiv bandura – an instrument which has become the workhorse of most professional bandurists in Ukraine. A slightly more refined instrument was also developed later by Vasyl Herasymenko in Lviv.

Although direct and open confrontation ceased, the Communist party continued to control and manipulate the art of the bandurist through a variety of indirect means. Bandura players now had to censor their repertoire and stop any cultural aspects that were deemed to be anti-Soviet. This included songs with religious texts or melodies, Christmas carols, historic songs about the cossack past, and songs with any hint of a nationalistic sub-text. Some bandurists rose in the ranks of the Communist Party to become high-level administrators. (e.g. Serhiy Bashtan was the first secretary of the Communist Party at the Kyiv conservatory for over 30 years and, in that position, restricted the development of many aspects of Ukrainian culture in the premier music establishment in Ukraine).

A policy of feminization of the bandura also severely restricted the number of male bandurists able to study the bandura at a professional level (kobzarstvo had originally been an exclusively male domain). This was perplexing as there was only one professional ensemble and it was made up exclusively of male players. The feminization of the instrument influenced a significant change in the repertoire of the bandurist from a heroic epic tradition to one singing romances. Restrictions existed in obtaining instruments and control was exercised in the publication of musical literature for the bandura. Only "trusted" performers were allowed to perform on stage with severely censored and restrictive repertoire. These restrictions continued to leave a significant impact on the contemporary development of the art form.

Restoration years

In the late 1970s these concert instruments began to be manufactured serially by the Chernihiv factory, and later the Lviv factory. In the mid-1970s artificial fingernails were also developed which allowed the bandurist to perform more professionally. In the 1960s the foundation of the modern professional bandura technique and repertoire were laid by Bashtan based on work he had done with students from the Kyiv Conservatory. Professional Ukrainian composers only started composing seriously for the instrument after World War II and specifically in the 1950-70's, including such composers as Mykola Dremliuha, Anatoly Kolomiyetz, Yuriy Oliynyk and Kost Miaskov, who have created complex works such as sonatas, suites, and concerti for the instrument.

In recent times, more Ukrainian composers have started to incorporate the bandura in their orchestral works, with traditional Ukrainian folk operas such as Natalka Poltavka being re-scored for the bandura. Contemporary works such as Kupalo by Y. Stankovych and The Sacred Dnipro by Valery Kikta also incorporated the bandura as part of the orchestra. Western composers of Ukrainian background, such as Oliynyk and Peter Senchuk, have also composed serious works for the bandura.

Today, all the conservatories of music in Ukraine offer courses majoring in bandura performance. Bandura instruction is also offered in all music colleges and most music schools, and it is now possible to get advanced degrees specialising in bandura performance and pedagogy. The most renowned of these establishments are the Kyiv and Lviv conservatories and the Kyiv University of Culture, primarily because of their well-established staff. Other centers of rising prominence are the Odessa Conservatory and Kharkiv University of Culture.

Present

The main modern band that plays bandura is Shpyliasti Kobzari. Most of compositions of Tin Sontsia contains bandura sound. That instrument sounds in some of HASPYD tracks.

Construction

The back of a traditional bandura is usually carved from a solid piece of wood (either willow, poplar, cherry or maple). Since the 1960s, glued-back instruments have also become common; even more recently, banduras have begun to be constructed with fiberglass backs. The soundboard is traditionally made from a type of spruce. The wrest planks and bridge are made from hard woods such as birch.

The instrument was originally a diatonic instrument and, despite the addition of chromatic strings in the 1920s, it has continued to be played as a diatonic instrument. Most contemporary concert instruments have a mechanism that allows for rapid re-tuning of the instrument into different keys. These mechanisms were first included in concert instruments in the late 1950s. Significant contributions to modern bandura construction were made by Khotkevych, Leonid Haydamaka, Peter Honcharenko, Skliar, Herasymenko and William Vetzal.

Today, there are four main types of bandura which differ in construction, holding, playing technique, repertoire, and sound.

Folk or Starosvitska Bandura

The Starosvitska bandura or traditional bandura, common from the late 18th century, is also sometimes referred to as folk or old-time bandura. These instruments usually have some 12-20-23 strings, tuned diatonically (4–6 bass strings and 16–18 treble strings known as prystrunky). These instruments are handmade, usually by local village violin makers with no two instruments being identical. The backs are usually hewn out of a single piece of wood, usually willow, and wooden pegs made of hard woods. The strings are tuned to a diatonic scale (major, minor, or modal) with bass strings tuned to corresponding I, IV, and V degrees of the diatonic row.

The instrument was used almost exclusively by itinerant blind epic singers in Ukraine, called kobzari. Traditionally these instruments had gut strings, however, after 1891 with the introduction of mass-produced violin strings steel strings began to become popular and by the beginning of the 20th century they were prevalent.

In the 1980s, there has been a revival of renewed interest in playing the authentic folk version of the bandura initiated by the students of Heorhy Tkachenko, notably Mykola Budnyk, Volodymyr Kushpet, Mykola Tovkailo, and Victor Mishalow. The movement has been continued by their students who have formed kobzar guilds Mikhailo Khai, Kost Cheremsky and Jurij Fedynskyj. Formal courses have been designed for the instrument as have been written handbooks. Several notable, present-day makers of the instrument include the late Budnyk, Tovkailo, Rusalim Kozlenko, Vasyl Boyanivsky, Fedynskyj, and Bill Vetzal. A category for authentic bandura playing has been included in the Hnat Khotkevych International Folk Instruments competition held in Kharkiv every 3 years.

Kyiv-style bandura

- A close-up of a Kyiv-style bandura's tuning pins.

- The strings are wrapped around tuning pins and rest on pegs.

- The longer bass strings are wound, and attached to the neck.

- A decorative rose near the sound hole on a Kyiv-style bandura.

- Chromatic and diatonic strings stretched over pegs on two levels, similar to black and white keys on a piano.

The Kyiv style or academic bandura is the most common instrument in use today in Ukraine.[9][citation needed] They have 55–65 metal strings (12 to 17 basses and 50 treble strings known as prystrunky) tuned chromatically through 5 octaves, with or without retuning mechanisms. The instruments are known as Kyiv-style banduras because they are constructed for players of the Kyiv-style technique pioneered by the Kyiv Bandurist Capella. Because the playing style was based on the techniques of the kobzars from Chernihiv, the instrument is occasionally referred to as the Chernihiv-style bandura.

Concert banduras are primarily manufactured by the Chernihiv Musical Instrument Factory or the Trembita Musical Instrument Factory in Lviv. Rarer instruments exist from the Melnytso-Podilsk and Kyiv workshops.[10] These instruments exist in two main types: 'Standard Prima' instruments and 'concert' instruments, which differ from the 'Prima' instruments in that they have a re-tuning mechanism placed in the upper wrest plank of the instrument.

'Concert' Kyiv-style banduras were first manufactured in Kyiv at a music workshop organized by Ivan Skliar from 1948–1954 and from 1952 by the Chernihiv Musical Instrument Factory. The Chernihiv factory stopped making banduras in 1991. Another line of Kyiv-style banduras was developed by Vasyl Herasymenko and continues to be made by the Trembita Musical Instrument Factory in Lviv. Rarer instruments also exist from the now defunct Melnytso-Podilsk experimental music workshop.

Kharkiv-style bandura

These instruments are primarily made by craftsmen outside of Ukraine; however, in more recent times, they have become quite sought after in Ukraine. They are strung either diatonically (with 34–36 strings) or chromatically (with 61–68 strings).

The standard Kharkiv bandura was first developed by Khotkevych and Haydamaka in the mid-1920s. A semi-chromatic version was developed by the Honcharenko brothers in the late 1940s. A number of instruments were made in the 1980s by Herasymenko. The Hnat Khotkevych Ukrainian Bandurist Ensemble in Australia was the only ensemble in the West to exploit the Kharkiv-style bandura.

Currently, Canadian bandura-maker Bill Vetzal has focused on making these instruments with some success. His latest instruments are fully chromatic, with re-tuning mechanism, and the backs are made of fibreglass. Additionally, Andrij (Andy) Birko, an American bandura maker, is also making Kharkiv instruments, applying construction and acoustic principles from guitars (both flat-top and arch-top) in an attempt to provide a more balanced and even tone to the instrument. Currently, he produces chromatic instruments but without re-tuning mechanisms.

Kyiv-Kharkiv Hybrid bandura

Attempts have been made to combine aspects of the Kharkiv and Kyiv banduras into a unified instrument. The first attempts were made by the Honcharenko brothers in Germany in 1948. Attempts were made in the 1960s by Skliar, in the 1980s by V. Herasymenko, and more recently by Vetzal in Canada.

Orchestral banduras

Orchestral banduras were first developed by Leonid Haydamaka in Kharkiv 1928 to extend the range of the bandura section in his orchestra of Ukrainian folk instruments. He developed piccolo- and bass-sized instruments tuned, respectively, an octave higher and lower than the standard Kharkiv bandura.

Other Kyiv-style instruments were developed by Ivan Skliar for use in the Kyiv Bandurist Capella, in particular alto-, bass- and contrabass-sized banduras. However, these instruments were not commercially available and were made in very small quantities.

Ensembles

The premier ensemble pioneering the bandura in performance in the West is the Ukrainian Bandurist Chorus. Other important bandura ensembles in the West that have made significant contributions to the art form are the Canadian Bandurist Capella and the Hnat Khotkevych Ukrainian Bandurist Ensemble.

Numerous similar ensembles have also become popular in Ukrainian centres, with some small ensembles becoming extremely popular.

See also

References

- ^ Крылатов, Юрий. "Взяв і я бандуру" [I also took a bandura]. pisni.org.ua. проект "Українські пісні" (project "Ukrainian songs"). Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Mizynec, V. Folk Instruments of Ukraine. Bayda Books, Melbourne, Australia, 1987, 48с.

- ^ Buckingham, James Silk; Sterling, John; Maurice, Frederick Denison; Stebbing, Henry; Dilke, Charles Wentworth; Hervey, Thomas Kibble; Dixon, William Hepworth; Maccoll, Norman; Murry, John Middleton (1874). The Athenaeum: A Journal of Literature, Science, the Fine Arts, Music, and the Drama. London: J. Francis. p. 270.

- ^ Findeizen, Nikolai (2008). History of Music in Russia from Antiquity to 1800, Vol. 1. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02637-8.

- ^ a b Jaffé, Daniel (2012). Historical Dictionary of Russian Music. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8108-5311-9.

- ^ Diakowsky, M. A Note on the History of the Bandura. The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S. 4, 3–4 №1419, N.Y. 1958, С.21–22.

- ^ Coughlan, Robert, Elizabeth and Catherine ISBN 9780451098405 p.59.

- ^ Ukrainian Bandurists Chorus #2 (78rpm album set). Ukrainian Bandurists Chorus. Ukrainian Bandurist's Chorus. 1951. No. 2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "The Ukrainian Bandura and its History – Ukrainian Bandurist Chorus". The UKRAINIAN BANDURIST CHORUS. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "OUR INSTRUMENT". www.bandura.org. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

Further reading

- Diakowsky, M. A Note on the History of the Bandura. The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S. 4, 3–4 no. 1419, N.Y. 1958, С.21–22

- Diakowsky, M. J. The Bandura. The Ukrainian Trend, 1958, no. I, С.18–36

- Diakowsky, M. Anyone can make a bandura – I did. The Ukrainian Trend, Volume 6

- Haydamaka, L. Kobza-bandura – National Ukrainian Musical Instrument. "Guitar Review" no. 33, Summer 1970 (С.13–18)

- Hornjatkevyč, A. The book of Kodnia and the three Bandurists. Bandura, #11–12, 1985

- Hornjatkevyč A. J., Nichols T. R. The Bandura. Canada crafts, April–May 1979 p. 28–29

- Mishalow, V. A Brief Description of the Zinkiv Method of Bandura Playing. Bandura, 1982, no. 2/6, С.23–26

- Mishalow, V. The Kharkiv style #1. Bandura 1982, no. 6, С.15–22 #2; Bandura 1985, no. 13-14, С.20–23 #3; Bandura 1988, no. 23-24, С.31–34 #4; Bandura 1987, no. 19-20, С.31–34 #5; Bandura 1987, no. 21-22, С.34–35

- Mishalow, V. A Short History of the Bandura. East European Meetings in Ethnomusicology 1999, Romanian Society for Ethnomusicology, Volume 6, С.69–86

- Mizynec, V. Folk Instruments of Ukraine. Bayda Books, Melbourne, Australia, 1987, 48с.

- Cherkaskyi, L. Ukrainski narodni muzychni instrumenty. (tr. "Ukrainian folk musical instruments ") Tekhnika, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2003, 262 pages. ISBN 966-575-111-5