Somali architecture

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Somalia |

|---|

| Culture |

| People |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Politics |

Somali architecture is the engineering and designing of multiple different construction types such as stone cities, castles, citadels, fortresses, mosques, temples, aqueducts, lighthouses, towers and tombs during the ancient, medieval and early modern periods in Somalia and other regions inhabited by Somalis, as well as the fusion of Somalo-Islamic architecture with Western designs in contemporary times.

Ancient

Walled settlements, temples and tombs

Some of the oldest known structures in the territory of modern-day Somalia consist of burial cairns (taalo).[1] Although found throughout the country and the larger Horn of Africa region, Somalia in particular is home to numerous such archaeological structures, with many similar edifices found at Haylan, Qa’ableh, Qombo'ul, El Ayo, Damo, Maydh and Heis among other towns. However, many of these ancient structures have yet to be properly explored, a process which would help shed further light on local history and facilitate their preservation for posterity.[1]

Houses were constructed of dressed stone similar to the ones in Ancient Egypt.[2] There are also examples of courtyards and large stone walls enclosing settlements, such as the Wargaade Wall.

Near Bosaso, at the end of the Baladi valley, lies a 2–3 km (1.2–1.9 mi) long earthwork.[1][3] Local tradition recounts that the massive embankment marks the grave of a community matriarch. It is the largest such structure in the wider Horn region.[3] In addition, old temples situated in the northwestern town of Sheekh are reportedly similar to those in the Deccan Plateau in the Indian subcontinent.[4] There also exist several ancient necropolises in Somalia. One such structured area is found on the country's northeastern tip, in the Hafun peninsula.[5]

Booco in the Aluula District contains a number of ancient structures. Two of these are enclosed platform monuments set together, which are surrounded by small stone circles. The circles of stone are believed to mark associated graves.[6]

Mudun is situated in the Wadi valley of the Iskushuban District. The area features a number of ruins, which local tradition holds belong to an ancient, large town. Among the old structures are around 2,000 tombs, which possess high towers and are dome-shaped.[1][3]

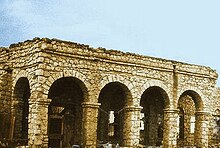

Port Dunford in the southern Lower Juba province contains a number of ancient ruins, including several pillar tombs. Prior to its collapse, one these structures' pillars stood 11 meters (36 ft) high from the ground, making it the tallest tower of its kind in the wider region.[7] The site is believed to correspond with the ancient emporium of Nikon, which is described in the 1st century CE Greco-Roman travelogue the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.[8] In the southern town of Hannassa, ruins of houses with archways and courtyards have been found along with other pillar tombs, including a rare octagonal tomb.[9] Additionally, various pillar tombs exist in the southeastern Marca area. Local tradition holds that these were built in the 16th century, when the Ajuran Sultanate's naa'ibs governed the district.[10]

Menhirs and dolmens

| Somali architecture |

|---|

On the coastal plain 20 km to Alula's east are found ruins of an ancient monument in a platform style. The structure is formed by a rectangular dry stone wall that is low in height; the space in between is filled with rubble and manually covered with small stones. Relatively large standing stones are also positioned on the edifice's corners. Near the platform are graves, which are outlined in stones. 24 m by 17 m in dimension, the structure is the largest of a string of ancient platform and enclosed platform monuments exclusive to far northeastern Somalia.[11]

Around 200 stone monuments (taalos) are found in the northeastern Botiala site, most of which consist of cairns. The bigger cairns are covered in shingles and tend to be more sturdily constructed. There are a number of rows of standing stones (menhirs) on the eastern side of the structures, which are similar to those at Salweyn, a great cairn-held situated close to Heis. Besides cairns, the Botiala area also features a few other drystone monuments. These include disc monuments with circular, ground-level features, as well as low, rectangular platform monuments.[12]

The northern town of Aw Barkhadle, named in honour of the 13th century scholar and saint Yusuf bin Ahmad al-Kawneyn (Aw Barkhadle), is surrounded by a number of ancient structures. Among these are menhirs, burial mounds, and dolmens.[13]

Stelae

Near the ancient northwestern town of Amud, whenever an old site had the prefix Aw in its name (such as the ruins of Awbare and Awbube[14]), it denoted the final resting place of a local saint.[15] Surveys by A.T. Curle in 1934 on several of these important ruined cities recovered various artefacts, such as pottery and coins, which point to a medieval period of activity at the tail end of the Adal Sultanate's reign.[14] Among these settlements, Aw Barkhadle is surrounded by a number of ancient stelae.[13] Burial sites near Burao likewise feature old stelae.[16]

Medieval

The introduction of Islam in the early medieval era of Somalia's history brought Islamic architectural influences from the Arabian Peninsula and Persia. This stimulated a shift from drystone and other related materials in construction to coral stone, sundried bricks, and the widespread use of limestone in Somali architecture. Many of the new architectural designs such as mosques were built on the ruins of older structures, a practice that would continue over and over again throughout the following centuries.[17]

Stone cities

The lucrative commercial networks of successive medieval Somali kingdoms and city-states such as the Adal Sultanate, Sultanate of Mogadishu, Ajuran Sultanate, and the Sultanate of the Geledi saw the establishment of several dozen stone cities in the interior of Somalia as well as the coastal regions. Ibn Battuta visiting Mogadishu in the early 14th century called it a town endless in size[18] and Vasco Da Gama who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre.[19]

Somali merchants were an integral part of a long distance caravan trade network connecting major Somali cities, such as Mogadishu, Merca, Zeila, Berbera, Bulhar and Barawa, with other business centers in the Horn of Africa. The numerous ruined and abandoned towns throughout the interior of Somalia can be explained as the remains of a once booming inland trade dating back to the medieval period.[20]

The interior cities of Amud and Abasa which flourished in the 15th century contained over 200 stone buildings of multiple stories and up to four rooms. The scattered ruins of the site cover an area of approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) in circumference.[21]

Goan Bogame, situated in the Las Anod District, contains the ruins of a large ancient city with around two hundred buildings. The structures were built in an architectural style similar to that of the edifices in Mogadishu's old Hamar Weine and Shangani districts.[1][3]

Citadels and city walls

City walls were established around the coastal cities of Merca, Barawa and Mogadishu to defend the cities against powers such as the Portuguese Empire. During the Adal Age, many of the inland cities such as Amud and Abasa in the northern part of Somalia were built on hills high above sea level with large defensive stone walls enclosing them. The Bardera militants during their struggle with the Geledi Sultanate had their main headquarters in the walled city of Bardera that was reinforced by a large fortress overseeing the Jubba river. In the early 19th century the citadel of Bardera was sacked by Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim and the city became a ghost town.

Somali city walls also acted as a barrier against the proliferation of arms usually carried by the Somali and Horn African nomads entering the cities with their caravan trains. They had to leave behind their weapons at the city gate before they could enter the markets with their goods and trade with the urban Somalis, Middle Easterners and Asian merchants.[22]

Mosques and shrines

Concordant with the ancient presence of Islam in the Horn of Africa region, mosques in Somalia are some of the oldest on the entire continent. One architectural feature distributing Somali mosques from other African mosques were minarets.

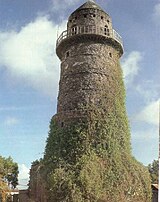

For centuries, Arba'a Rukun (1269), the Friday mosque of Merca (1609) and Fakr ad-Din (1269) were the only mosques in East Africa to have minarets.[23][24] Arba Rukun's massive round coral tower of about 13.5 meters (44 ft) high and over 4 meters (13 ft) in diameter at its base has a doorway that is narrow and surrounded by a multiple ordered recessed arch, which may be the first example of the recessed arch that was to become a prototype for the local mihrab style.

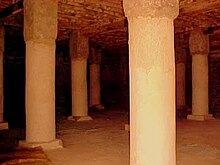

Constructed by and named after the first Sultan of the Mogadishu Sultanate, the Fakr-ad Din mosque dates back to the 1269. Built with marble and coral stone on a compact rectangular plan, it features a domed mihrab (indicator of the direction of Mecca). Glazed tiles were also used in the decoration of the mihrab, one of which bears a dated inscription. In addition, the masjid is characterized by a system of composite beams, alongside two main columns. This well-planned, sophisticated design is not replicated in mosques further south outside the Horn region.[25]

The 13th century Al Gami University consisted of a rectangular base with a large cylindrical tower architecturally unique in the Islamic world.

Shrines erected to house and honor Somali patriarchs and forefathers evolved from ancient Somali burial customs. Such tombs, which are predominantly found in northern Somalia (the suggested point of origin of the Somalia's majority Somali ethnic group), feature structures mainly consisting of domes and square plans.[26] In southern Somalia, the preferred medieval shrine architecture was the pillar tomb-style.

A number of ancient burial sites dated from the pre-Islamic period sit atop the peak of Buur Heybe, a granitic inselberg in the southern Doi belt. They serve as a center of annual pilgrimage (siyaro). These burial sites on the mountain's summit were later made into Muslim holy sites in the ensuing Islamic period, including the Owol Qaasing (derived from the Arabic "Abul Qaasim", one of the names of Muhammad) and Sheikh Abdulqadir al-Jilaani (named for the founder of the Qadiriyya order).[27]

Towers and lighthouses

Somalia's historical strategic location within the world's oldest and busiest sealanes encouraged the construction of lighthouses to co-ordinate shipping and to ensure the safe entrance of commercial vessels in the nation's many port cities. In times of weak central authority the Somali civilizational matrix of interior cities and port cities was based on a clan formula that saw various clans in fierce competition over natural resources that led to chronic feuding between neighbours. Towers provided the merchant class and the urban population protection against potential raids from the nomadic regions. Stone towers such as the 15th century Almnara tower in Mogadishu and the Jamia tower of Merca were also built for defence.

Early modern era

Qalcads

The early modern or colonial period saw a continuation in the use of materials such as coral stone, sundried bricks and limestone in Somali architecture which with the increasing European influence on the Somali peninsula was now being complemented by new construction materials such as cement. The period was characterised by military architecture in the form of multi-purpose forts, and the construction of new ports. The Sultans of Aluula in the northern part of the country and the Geledi Sultanate in the south were at their peak during this period, and many of the castles, palaces and forts found in various Somali cities originate from that era.

Throughout the medieval era, castles and fortresses known as Qalcads were built by Somali Sultans for protection against both foreign and domestic threats. The major medieval Somali power engaging in castle building was the Ajuran Sultanate, and many of the hundreds of ruined fortifications dotting the landscapes of Somalia today are attributed to Ajuran engineers.[28]

In the year 1845, Haji Sharmarke Ali Saleh seized Berbera, constructed four Martello style forts within the vicinity of the town, and garrisoned each fort with thirty matchlock men.[29]

Dhulbahante garesas

In the Sayid's description of the fall of Taleh in February 1920, in an April 1920 letter transcribed from the original Arabic script into Italian by the incumbent Governatori della Somalia, the various Darawiish-built installations are described as garesas taken from the Dhulbahante clan by the British:[30][31]

i Dulbohanta nella maggior parte si sono arresi agli inglesi e han loro consegnato ventisette garese (case) ricolme di fucili, munizioni e danaro. |

the Dhulbahante surrendered for the most part to the British and handed twenty-seven garesas (houses) full of guns, ammunition and money over to them. |

The Dar Ilalo stone towers though initially constructed to defend the fortress of Taleex were also used as granaries for the Dervish State.

The Dervish State in the late 19th century and early 20th century was another prolific fortress building power in the Somali Peninsula. In 1909, after the British withdrawal to the coast, the permanent capital and headquarters of the Dervishes was constructed at Taleh, a large walled town with fourteen fortresses. The main fortress, Silsilat, included a walled garden and a guard house. It became the residence of Diiriye Guure, his wives, family, prominent Somali military leaders, and also hosted several Turkish, Yemeni and German dignitaries, architects, masons and arms manufacturers.[32] Several dozen other Dhulbahante garesas were built in Illig, Eyl, Shimbiris and other parts of the Horn of Africa.

1990s to present

In the modern period, several Somali cities such as Mogadishu, Hargeisa and Garowe received large projects, which saw construction in new styles that harmoniously blended in with the existing old architecture.

Due to Italian influence, parts of Mogadishu are built in the classical style: from the Villa Somalia (official residency of the presidents of Somalia) to the Governor's Palace of Mogadishu and the "Fiat Boero" building there are many examples of this architecture, that was developed when Mogadishu was under Italian rule. Other areas of Somalia show the Italian influence, like in the famous lighthouse in Guardafui cape.

The Somali government continued upon that legacy, while also opening the door to German, American and Chinese designers.

As a departure from the prevailing Somali architectural style, the National Theatre in Mogadishu was completely built from a Chinese perspective. The town-hall was constructed in the Moroccan style. Much of the new architecture also continued upon ancient tradition, the Al-Uruba Hotel, the pre-eminent hotel in Somalia and an iconic feature of Mogadishu's waterfront was entirely designed and constructed by Somalis in the Arabesque style.

In recent times, due to the civil war and the subsequent decentralization, many cities across the country have rapidly developed into urban hubs and have adopted their own architectural styles independently.

In the cities of Mogadishu, Hargeisa, Berbera and Bosaso, construction firms have built hotels, government facilities, airports and residential neighborhoods in a modernist style, often utilizing chrome, steel and glass materials.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Hodd, Michael (1994). East African Handbook. Trade & Travel Publications. p. 640. ISBN 978-0-8442-8983-0.

- ^ Man, God and Civilization pg 216

- ^ a b c d Ali, Ismail Mohamed (1970). Somalia Today: General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic. p. 295.

- ^ Pease, Alfred E. (1898). "Some account of Somaliland: With Notes on Journeys Through the Gadabürsi and Western Ogaden countries, 1896–1897". Scottish Geographical Magazine. 14 (2): 57–73. doi:10.1080/00369229808732974.

- ^ National Review (1965). Somalia Calling the World. p. 25.

- ^ Somali Studies International Association, Hussein Mohamed Adam, Charles Lee Geshekter (ed.) (1992). The Proceedings of the First International Congress of Somali Studies. Scholars Press. pp. 37 & 40. ISBN 978-0891306580. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hussein Mohamed Adam, Charles Lee Geshekter (ed.) (1992). The Proceedings of the First International Congress of Somali Studies. Scholars Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0891306580. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. University of California Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0520066977. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ Sanseverino, Hilary Costa (1983). "Archaeological Remains on the Southern Somali Coast". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 18 (1): 151–164. doi:10.1080/00672708309511319.

- ^ Cassanelli, Lee V. (1982). The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600 to 1900. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0812278323. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Chittick, Neville (1975). An Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition. pp. 117–133.

- ^ Chittick, Neville (1984). Newsletter of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists, Issues 24-32. Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ a b Briggs, Phillip (2012). Somaliland. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-84162-371-9.

- ^ a b Lewis, I.M. (1998). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-56902-103-3.

- ^ G.W.B. Huntingford, "The Town of Amud, Somalia", Azania, 13 (1978), p. 184

- ^ "National Museums". Somali Heritage and Archaeology. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.102.

- ^ The Archaeology of Islam in Sub Saharan Africa pg 62

- ^ Da Gama's First Voyage pg.88

- ^ Shaping of Somali Society - Lee Cassanelli pg.149

- ^ Briggs, Philip (2012). Somaliland: with the overland route from Addis Ababa via eastern Ethiopia (1st ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781784776053.

The house are scattered around without any apparent plan; there are no streets and no trace of a surrounding wall. There is a mosque in the southern half of the dwelling area... [with a] rather oddly built mihrab facing the entrance... and immediately to the south... is the cemetery. There are upwards of two hundred houses, all well-built of stone [and] as much as 2.6m in height... The number of rooms ranges from two to four... there is sometimes no sign of an entrance to the inner rooms. This implies that entry was made from the roof, which was doubtless flat and reached by teps now vanished... There are many niches or cupboards in the inner walls.

- ^ Tales which persist on the Tongue - Scott S. Reese pg 4

- ^ Studies in Islamic history and civilization By David Ayalon pg 370

- ^ Asghar, Ajaz. "Medieval to Postmodern Somali architecture and the incorporation of local elements and styles through the ages – Architects77". Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ Peter S. Garlake, Early art and architecture of Africa, (Oxford University Press US: 2002), p.176.

- ^ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.8.

- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0810866041. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ Shaping of Somali Society pg 101

- ^ Transactions of the Bombay Geographical Society, 1849, Volume 8, p. 185.

- ^ Ferro e Fuoco in Somalia, da Francesco Saverio Caroselli, Rome, 1931; p. 272.

- ^ Ciise, Jaamac (1976). Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan.

Per tal fatto ci siamo sabandati e non c'e ' stato piu ' accordo fra di noi : i Dulbohanta nella maggior parte si sono arresi agli inglesi c han loro consegnato ventisette garese case ) ricolme di fucili , munizioni e danaro .

- ^ Taleh W. A. MacFadyen The Geographical Journal, Vol. 78, No. 2 (Aug., 1931), pp. 125-128