Arabization

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Arabization or Arabicization (Arabic: تعريب, romanized: taʻrīb) is a sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Arab society becomes Arab, meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Arabic language, culture, literature, art, music, and ethnic identity as well as other socio-cultural factors. It is a specific form of cultural assimilation that often includes a language shift.[1] The term applies not only to cultures, but also to individuals, as they acclimate to Arab culture and become "Arabized". Arabization took place after the Muslim conquest of the Middle East and North Africa, as well as during the more recent Arab nationalist policies toward non-Arab minorities in modern Arab states, such as Algeria,[2] Iraq,[3] Syria,[4] Egypt,[5] Bahrain,[6] and Sudan.[2]

After the rise of Islam in the Hejaz and subsequent Muslims conquests, Arab culture and language spread outside the Arabian Peninsula through trade and intermarriages between members of the non-Arab local population and the peninsular Arabs. The Arabic language began to serve as a lingua franca in these areas and various dialects were formed. This process was accelerated by the migration of various Arab tribes outside of Arabia, such as the Arab migrations to the Maghreb and the Levant.

The influence of Arabic has been profound in many other countries whose cultures have been influenced by Islam. Arabic was a major source of vocabulary for various languages. This process reached its zenith between the 10th and 14th centuries, widely considered to be the high point of Arab culture, during the Islamic Golden Age.

Early Arab expansion in the Near East

After Alexander the Great, the Nabataean Kingdom emerged and ruled a region extending from north of Arabia to the south of Syria. The Nabataeans originated from the Arabian peninsula, who came under the influence of the earlier Aramaic culture, the neighbouring Hebrew culture of the Hasmonean kingdom, as well as the Hellenistic cultures in the region (especially with the Christianization of Nabateans in the 3rd and 4th centuries). The pre-modern Arabic language was created by Nabateans, who developed the Nabataean alphabet which became the basis of modern Arabic script. The Nabataean language, under heavy Arab influence, amalgamated into the Arabic language.

The Arab Ghassanids were the last major non-Islamic Semitic migration northward out of Yemen in late classic era. They were Greek Orthodox Christian, and clients of the Byzantine Empire. They arrived in Byzantine Syria which had a largely Aramean population. They initially settled in the Hauran region, eventually spreading to the entire Levant (modern Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan), briefly securing governorship of parts of Syria and Transjordan away from the Nabataeans.

The Arab Lakhmid Kingdom was founded by the Lakhum tribe that emigrated from Yemen in the 2nd century and ruled by the Banu Lakhm, hence the name given it. They adopted the religion of the Church of the East, founded in Assyria/Asōristān, opposed to the Ghassanids Greek Orthodox Christianity, and were clients of the Sasanian Empire.

The Byzantines and Sasanians used the Ghassanids and Lakhmids to fight proxy wars in Arabia against each other.

History of Arabization

Arabization during the early Caliphate

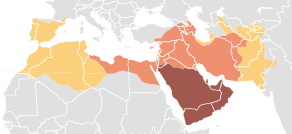

The most significant wave of "Arabization" in history followed the early Muslim conquests of Muhammad and the subsequent Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates. These Arab empires were the first to grow well beyond the Arabian Peninsula, eventually reaching as far as Iberia in the West and Central Asia to the East, covering 11,100,000 km2 (4,300,000 sq mi),[7] one of the largest imperial expanses in history.

Southern Arabia

South Arabia is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it also included Najran, Jizan, and 'Asir, which are presently in Saudi Arabia, and the Dhofar of present-day Oman.

Old South Arabian was driven to extinction by the Islamic expansion, being replaced by Classical Arabic which is written with the Arabic script. The South Arabian alphabet which was used to write it also fell out of use. A separate branch of South Semitic, the Modern South Arabian languages still survive today as spoken languages in southern of present-day Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Dhofar in present-day Oman.

Although Yemen is traditionally held to be the homeland of the Qahtanite Arabs who, according to Arab tradition, are pure Arabs; however, most[8][9] of the sedentary Yemeni population did not speak Old Arabic prior to the spread of Islam, and spoke the extinct Old South Arabian languages instead.[10][11]

Eastern and Northern Arabia

Before the 7th century CE, the population of Eastern Arabia consisted of Christian Arabs, Zoroastrian Arabs, Jews, and Aramaic-speaking agriculturalists.[12][13][14][15] Some sedentary dialects of Eastern Arabia exhibit Akkadian, Aramaic and Syriac features.[16][17] The sedentary people of ancient Bahrain were Aramaic speakers and to some degree Persian speakers, while Syriac functioned as a liturgical language.[14]

Even within Northern Arabia, Arabization occurred to non-Arab populations such as the Hutaym in the northwestern Arabia and the Solluba in the Syrian Desert and the region of Mosul.[18]

The Levant

On the eve of the Rashidun Caliphate conquest of the Levant, 634 AD, Syria's population mainly spoke Aramaic; Greek was the official language of administration. Arabization and Islamization of Syria began in the 7th century, and it took several centuries for Islam, the Arab identity, and language to spread;[19] the Arabs of the caliphate did not attempt to spread their language or religion in the early periods of the conquest, and formed an isolated aristocracy.[20] The Arabs of the caliphate accommodated many new tribes in isolated areas to avoid conflict with the locals; caliph Uthman ordered his governor, Muawiyah I, to settle the new tribes away from the original population.[21] Syrians who belonged to Monophysitic denominations welcomed the peninsular Arabs as liberators.[22]

The Abbasids in the eighth and ninth century sought to integrate the peoples under their authority, and the Arabization of the administration was one of the tools.[23] Arabization gained momentum with the increasing numbers of Muslim converts;[19] the ascendancy of Arabic as the formal language of the state prompted the cultural and linguistic assimilation of Syrian converts.[24] Those who remained Christian also became Arabized;[23] it was probably during the Abbasid period in the ninth century that Christians adopted Arabic as their first language; the first translation of the gospels into Arabic took place in this century.[25] Many historians, such as Claude Cahen and Bernard Hamilton, proposed that the Arabization of Christians was completed before the First Crusade.[26] By the thirteenth century, Arabic language achieved dominance in the region and its speakers became Arabs.[19]

Egypt

Prior to the Islamic conquests, Arabs had been inhabiting the Sinai Peninsula, the Eastern desert and eastern Delta for centuries.[27] These regions of Egypt collectively were known as "Arabia" to the contemporary historians and writers documenting them.[28] Several pre-Islamic Arab kingdoms, such as the Qedarite Kingdom, extended into these regions. Inscriptions and other archeological remains, such as bowls bearing inscriptions identifying Qedarite kings and Nabatean Arabic inscriptions, affirm the Arab presence in the region.[29] Egypt was conquered from the Romans by the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century CE. The Coptic language, which was written using the Coptic variation of the Greek alphabet, was spoken in most of Egypt prior to the Islamic conquest. Arabic, however, was already being spoken in the eastern fringes of Egypt for centuries prior to the arrival of Islam.[30] By the Mameluke era, the Arabization of the Egyptian populace alongside a shift in the majority religion going from Christianity to Islam, had taken place.[31]

The Maghreb

Neither North Africa nor the Iberian Peninsula were strangers to Semitic culture: the Phoenicians and later the Carthaginians dominated parts of the North African and Iberian shores for more than eight centuries until they were suppressed by the Romans and by the following Vandal and Visigothic invasions, and the Berber incursions.

From the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb in the 7th century, Arabs began to migrate to the Maghreb in several waves. Arab migrants settled in all parts of the Maghreb, coming as peaceful newcomers who were welcomed everywhere, establishing large Arab settlements in many areas.[32] In addition to changing the population's demographics, the early migration of Arab tribes resulted in the Arabization of the native Berber population. This initial wave contributed to the Berber adoption of Arab culture. Furthermore, the Arabic language spread during this period and drove local Latin (African Romance) into extinction in the cities. The Arabization took place around Arab centres through the influence of Arabs in the cities and rural areas surrounding them.[33]

Arab political entities in the Maghreb such as the Aghlabids, Idrisids, Salihids and Fatimids, were influential in encouraging Arabization by attracting Arab migrants and by promoting Arab culture. In addition, disturbances and political unrest in the Mashriq compelled the Arabs to migrate to the Maghreb in search of security and stability.[33]

After establishing Cairo in 969, the Fatimids left rule over Tunisia and eastern Algeria to the local Zirid dynasty (972–1148).[34] In response to the Zirids later declaring independence from the Fatimids, the Fatimids dispatched large Bedouin Arab tribes, mainly the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, to defeat the Zirids and settle in the Maghreb. The invasion of Ifriqiya by the Banu Hilal, a warlike Arab Bedouin tribe, sent the region's urban and economic life into further decline.[34] The Arab historian Ibn Khaldun wrote that the lands ravaged by Banu Hilal invaders had become completely arid desert.[35][36] The Fatimid caliph instructed the Bedouin tribes to rule the Maghreb instead of the Zirid emir Al-Mu'izz and told them "I have given you the Maghrib and the rule of al-Mu'izz ibn Balkīn as-Sanhājī the runaway slave. You will want for nothing." and told Al-Mu'izz "I have sent you horses and put brave men on them so that God might accomplish a matter already enacted". Sources estimated that the total number of Arab nomads who migrated to the Maghreb in the 11th century was at around 1 million Arabs.[37] There were later Arab migrations to the Maghreb by Maqil and Beni Hassan in the 13th-15th century and by Andalusi refugees in the 15th-17th century.

The migration of Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym in the 11th century had a much greater influence on the process of Arabization of the population than did the earlier migrations. It played a major role in spreading Bedouin Arabic to rural areas such as the countryside and steppes, and as far as the southern areas near the Sahara.[33] It also heavily transformed the culture of the Maghreb into Arab culture, and spread nomadism in areas where agriculture was previously dominant.[38]

Al-Andalus

After the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, under the Arab Muslim rule Iberia (al-Andalus) incorporated elements of Arabic language and culture. The Mozarabs were Iberian Christians who lived under Arab Islamic rule in Al-Andalus. Their descendants remained unconverted to Islam, but did however adopt elements of Arabic language and culture and dress. They were mostly Roman Catholics of the Visigothic or Mozarabic Rite. Most of the Mozarabs were descendants of Hispano–Gothic Christians and were primarily speakers of the Mozarabic language under Islamic rule. Many were also what the Arabist Mikel de Epalza calls "Neo-Mozarabs", that is Northern Europeans who had come to the Iberian Peninsula and picked up Arabic, thereby entering the Mozarabic community.

Besides Mozarabs, another group of people in Iberia eventually came to surpass the Mozarabs both in terms of population and Arabization. These were the Muladi or Muwalladun, most of whom were descendants of local Hispano-Basques and Visigoths who converted to Islam and adopted Arabic culture, dress, and language. By the 11th century, most of the population of al-Andalus was Muladi, with large minorities of other Muslims, Mozarabs, and Sephardic Jews. It was the Muladi, together with the Berber, Arab, and other (Saqaliba and Zanj) Muslims who became collectively termed in Christian Europe as "Moors".

The Andalusian Arabic was spoken in Iberia during Islamic rule.

Sicily, Malta, and Crete

A similar process of Arabization and Islamization occurred in the Emirate of Sicily (as-Siqilliyyah), Emirate of Crete (al-Iqritish), and Malta (al-Malta), during this period some segments of the populations of these islands converted to Islam and began to adopt elements of Arabic culture, traditions, and customs. The Arabization process also resulted in the development of the now extinct Siculo-Arabic language, from which the modern Maltese language derives. By contrast, the present-day Sicilian language, which is an Italo-Dalmatian Romance language, retains very little Siculo-Arabic, with its influence being limited to some 300 words.[39]

Sudan

Contacts between Nubians and Arabs long predated the coming of Islam,[citation needed] but the Arabization of the Nile Valley was a gradual process that occurred over a period of nearly one thousand years. Arab nomads continually wandered into the region in search of fresh pasturage, and Arab seafarers and merchants traded at Red Sea ports for spices and slaves. Intermarriage and assimilation also facilitated Arabization. Traditional genealogies trace the ancestry of the Nile valley's area of Sudan mixed population to Arab tribes that migrated into the region during this period. Even many non-Arabic-speaking groups claim descent from Arab forebears. The two most important Arabic-speaking groups to emerge in Nubia were the Ja'alin and the Juhaynah.

In the 12th century, the Arab Ja'alin tribe migrated into Nubia and Sudan and gradually occupied the regions on both banks of the Nile from Khartoum to Abu Hamad. They trace their lineage to Abbas, uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. They are of Arab origin, but now of mixed blood mostly with Northern Sudanese and Nubians.[40][41] In the 16th and 17th centuries, new Islamic kingdoms were established – the Funj Sultanate and the Sultanate of Darfur, starting a long period of gradual Islamization and Arabization in Sudan. These sultanates and their societies existed until the Sudan was conquered by the Ottoman Egyptian invasion in 1820, and in the case of Darfur, even until 1916.[42]

In 1846, Arab Rashaida, who speak Hejazi Arabic, migrated from the Hejaz in present-day Saudi Arabia into what is now Eritrea and north-east Sudan, after tribal warfare had broken out in their homeland. The Rashaida of Sudan live in close proximity with the Beja people, who speak Bedawiye dialects in eastern Sudan.[43]

The Sahel

In medieval times, the Baggara Arabs, a grouping of Arab ethnic groups who speak Shuwa Arabic (which is one of the regional varieties of Arabic in Africa), migrated into Africa, mainly between Lake Chad and southern Kordofan.

Currently, they live in a belt which stretches across Sudan, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic and South Sudan and they number over six million people. Like other Arabic speaking tribes in the Sahara and the Sahel, Baggara tribes have origin ancestry from the Juhaynah Arab tribes who migrated directly from the Arabian peninsula or from other parts of north Africa. [44]

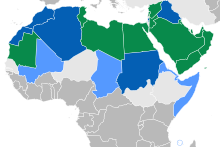

Arabic is an official language of Chad and Sudan as well as a national language in Niger, Mali, Senegal, and South Sudan. In addition, Arabic dialects are spoken of minorities in Nigeria, Cameroon, and Central African Republic.

Arabization in modern times

In the modern era, Arabization occurred due to the Arab nationalist policies toward non-Arab minorities in modern Arab states, including Algeria,[2] Iraq,[3] Syria,[45] Egypt,[46] Bahrain,[47] Kuwait,[48] and Sudan.[2] Modern Arabization also occurred to reverse the consequences of European colonialism.[49] Arab governments often imposed policies that sought to promote the use of Modern Standard Arabic and eliminate the languages of former colonizers, such as the reversing of street signs from French to Arabic names in Algeria.[50]

Arabization in Algeria

Modern Arabization in Algeria took place to develop and promote Arabic into the nation's education system, government, and media in order to replace the former language that was enforced due to colonization, French.[51] Algeria had been conquered by France and even made to be part of its metropolitan core for 132 years, a significantly longer timespan compared to Morocco and Tunisia, and it was also more influenced by Europe due to the contiguity with French settlers in Algeria: both Algerian and French nationals used to live in the same towns, resulting in the cohabitation of the two populations.[52]

While trying to build an independent and unified nation-state after the Evian Accords, the Algerian government under Ahmed Ben Bella's rule began a policy of Arabization. Indeed, due to the lasting and deep colonization, French was the major administrative and academic language in Algeria, even more so than in neighboring countries. Since independence, Algerian nationalism was heavily influenced Arab socialism, Islamism and Arab nationalism.[53][54]

The unification and pursuit of a single Algerian identity was to be found in the Arab identity, Arabic language and religion. Ben Bella composed the Algerian constitution in October 1963, which asserted that Islam was the state religion, Arabic was the sole national and official language of the state, Algeria was an integral part of the Arab world, and that Arabization was the first priority of the country to reverse French colonization.[55][56] According to Abdelhamid Mehri, the decision of Arabic as an official language was the natural choice for Algerians, even though Algeria is a plurilingual nation with a minority, albeit substantial, number of Berbers within the nation, and the local variety of Arabic used in every-day life, Algerian Arabic, was distinct from the official language, Modern Standard Arabic.[57]

However, the process of Arabization was meant not only to promote Islam, but to fix the gap and decrease any conflicts between the different Algerian ethnic groups and promote equality through monolingualism.[58] In 1964 the first practical measure was the Arabization of primary education and the introduction of religious education, the state relying on Egyptian teachers – belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood and therefore particularly religious[59] – due to its lack of literary Arabic-speakers. In 1968, during the Houari Boumediene regime, Arabization was extended, and a law[60] tried to enforce the use of Arabic for civil servants, but again, the major role played by French was only diminished.

The whole policy was ultimately not as effective as anticipated: French has kept its importance[61] and Berber opposition kept growing, contributing to the 1988 October Riots. Some Berber groups, like the Kabyles, felt that their ancestral culture and language were threatened and the Arab identity was given more focus at the expense of their own. After the Algerian Civil War, the government tried to enforce even more the use of Arabic,[62] but the relative effect of this policy after 1998 (the limit fixed for complete Arabization) forced the heads of state to make concessions towards Berber, recognizing it in 2002[63] as another national language that will be promoted. However, because of literary Arabic's symbolic advantage, as well as being a single language as opposed to the fragmented Berber languages, Arabization is still a goal for the state, for example with laws on civil and administrative procedures.[64]

Arabization in Oman

Despite being a nation of the Arabian Peninsula, Oman had been home to several native languages other than Arabic,[65] of which Kumzari which is the only native Indo-European language in the Arabian Peninsula has been classified as highly endangered by the UNESCO and at risk of dying out in 50 years.[66] Before the takeover of Qaboos as sultan, Arabic was only ever spoken by the inhabitants outside the village of Kumzar, in mosques or with strangers, however since the introduction of Arabic-only schools in 1984, Arabic is hence now spoken at both school and village with it being mandatory in school and as TV and radio are also in Arabic meaning virtually all media the people of Kumzar are exposed to is in Arabic.[67] There has also been an internalization of outsiders' negative attitudes toward the Kumzari language to the point where some Kumzari families have begun to speak Arabic to their children at home.[68]

The Modern South Arabian languages have also come under threat in Oman. Hobyot is considered a critically endangered language.[69] The actual number of speakers is unknown, but it is estimated to be only a few hundred. Most of those who maintain the language are elderly, which adds to the likelihood that language extinction is near. Ethnologue categorizes it as a moribund language (EGIDS 8a). The only fluent speakers that are left are older than the child-bearing age, which ultimately makes integration of the language into subsequent generations highly improbable.[70] Mechanisms of transmission would have to be created from outside the community in order to preserve it.

The Harsusi language is also critically endangered, as most Harsusi children now attend Arabic-language schools and are literate in Arabic, Harsusi is spoken less in the home, meaning that it is not being passed down to future generations.[71] With the discovery of oil in the area and the reintroduction of the Arabian Oryx in the area which has provided job opportunities for Harsusi men, this has led to them using primarily Arabic or Mehri when communicating with their co-workers.[72] These factors have also caused many Harasis to speak Arabic and Mehri in addition to or in place of Harsusi. These pressures led one researcher to conclude in 1981 that "within a few generations Harsusi will be replaced by Arabic, more specifically by the Omani Arabic standard dialect"[73] though this has not yet materialized. UNESCO has categorised Harsusi as a language that is "definitely endangered".[74]

The Shehri language has also come under threat in recent years, prior to the Arabization of Oman, Shehri was once spoken from Yemen's Hadhramaut region to Ras Al Hadd in Eastern Oman.[75] Until around as little as forty years ago, Shehri was spoken by all of the inhabitants of Dhofar as the common language, including by the native Arabic speakers in Salalah who spoke it fluently. The remainder of Dhofar's inhabitants all spoke Shehri as their mother tongue. Today however Arabic has taken over as the form of mutual communication in Dhofar and is now exclusively spoken by those to whom it is their native tongue. A number of the older generation of Shehri language speakers, particularly those who live in the mountains, don't even speak Arabic and it was only around fifty years ago that most of Dhofar's Shehri speaking population began to learn it. The fact that Arabic has a written form unlike Shehri has also greatly contributed to its decline.[76]

Another language, Bathari is the most at risk of dying out with its numbers (as of 2019) at currently anywhere from 12 to 17 fluent elderly speakers whereas there are some middle aged speakers but they mix their ancestral tongue with Arabic instead.[77] The tribe seems to be dying out with the language also under threat from modern education solely in Arabic. The Bathari language is nearly extinct. Estimates are that the number of remaining speakers are under 100.[78]

Arabization in Morocco

Following 44 years of colonization by France,[52] Morocco began promoting the use of Modern Standard Arabic to create a united Moroccan national identity, and increase literacy throughout the nation away from any predominant language within the administration and educational system. Unlike Algeria, Morocco did not encounter with the French as strongly due to the fact that the Moroccan population was scattered throughout the nation and major cities, which resulted in a decrease of French influence compared to the neighboring nations.[52]

First and foremost, educational policy was the main focus within the process, debates surfaced between officials who preferred a "modern and westernized" education with enforcement of bilingualism while others fought for a traditional route with a focus of "Arabo-Islamic culture".[79] Once the Istiqal Party took power, the party focused on placing a language policy siding with the traditional ideas of supporting and focusing on Arabic and Islam.[79] The Istiqal Party implemented the policy rapidly and by the second year after gaining independence, the first year of primary education was completely Arabized, and a bilingual policy was placed for the remaining primary education decreasing the hours of French being taught in a staggered manner.[79]

Arabization in schools had been more time-consuming and difficult than expected due to the fact that the first 20 years following independence, politicians (most of which were educated in France or French private school in Morocco) were indecisive as to if Arabization was best for the country and its political and economic ties with European nations.[52] Regardless, complete Arabization can only be achieved if Morocco becomes completely independent from France in all aspects; politically, economically, and socially. Around 1960, Hajj Omar Abdeljalil the education minister at the time reversed all the effort made to Arabize the public school and reverted to pre-independent policies, favoring French and westernized learning.[52] Another factor that reflected the support of reversing the Arabization process in Morocco, was the effort made by King Hassan II, who supported the Arabization process but on the contrary increased political and economic dependence on France.[52] Due to the fact that Morocco remained dependent on France and wanted to keep strong ties with the Western world, French was supported by the elites more than Arabic for the development of Morocco.[52]

Arabization in Tunisia

The Arabization process in Tunisia theoretically should have been the easiest within the North African region because less than 1% of its population was Berber, and practically 100% of the population natively spoke vernacular Tunisian Arabic.[52][80] However, it was the least successful due to its dependence on European nations and belief in Westernizing the nation for the future development of the people and the country. Much like Morocco, Tunisian leaders' debate consisted of traditionalists and modernists, traditionalists claiming that Arabic (specifically Classical Arabic) and Islam are the core of Tunisia and its national identity, while modernists believed that Westernized development distant from "Pan-Arabist ideas" are crucial for Tunisia's progress.[80] Modernists had the upper hand, considering elites supported their ideals, and after the first wave of graduates that had passed their high school examinations in Arabic were not able to find jobs nor attend a university because they did not qualify due to French preference in any upper-level university or career other than Arabic and Religious Studies Department.[80]

There were legitimate efforts made to Arabize the nation from the 1970s up until 1982, though the efforts came to an end and the process of reversing all the progress of Arabization began and French implementation in schooling took effect.[80] The Arabization process was criticized and linked with Islamic extremists, resulting in the process of "Francophonie" or promoting French ideals, values, and language throughout the nation and placing its importance above Arabic.[80] Although Tunisia gained its independence, nevertheless the elites supported French values above Arabic, the answer to developing an educated and modern nation, all came from Westernization. The constitution stated that Arabic was the official language of Tunisia but nowhere did it claim that Arabic must be utilized within the administrations or every-day life, which resulted in an increase of French usage not only in science and technology courses. Further, major media channels were in French, and government administrations were divided—some were in Arabic while others were in French.[80]

Arabization in Sudan

Sudan is an ethnically mixed country that is economically and politically dominated by the society of central northern Sudan, where many identify as Arabs and Muslims. The population in South Sudan consists mostly of Christian and Animist Nilotic people, who have been regarded for centuries as non-Arab, African people. Apart from Modern Standard Arabic, taught in schools and higher education, and the spoken forms of Sudanese Arabic colloquial, several other languages are spoken by diverse ethnic groups.

Since independence in 1956, Sudan has been a multilingual country, with Sudanese Arabic as the major first or second language. In the 2005 constitution of the Republic of Sudan and following the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, the official languages of Sudan were declared Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and English. Before the independence of South Sudan in 2011, people in the southern parts of the country, who mainly speak Nilo-Saharan languages or Juba Arabic, were subjected to the official policy of Arabization by the central government. The constitution declared, however, that "all indigenous languages of the Sudan are national languages and shall be respected, developed, and promoted," and it allowed any legislative body below the national level to adopt any other national language(s) as additional official working language(s) within that body's jurisdiction.[81]

MSA is also the language used in Sudan's central government, the press, as well as in official programmes of Sudan television and Radio Omdurman. Several lingua francas have emerged, and many people have become genuinely multilingual, fluent in a native language spoken at home, a lingua franca, and perhaps other languages.[81]

Arabization in Mauritania

Mauritania is an ethnically-mixed country that is economically and politically dominated by those who identify as Arabs and/or Arabic-speaking Berbers. About 30% of the population is considered "Black African", and the other 40% are Arabized Blacks, both groups suffering high levels of discrimination.[82] Recent Black Mauritanian protesters have complained of "comprehensive Arabization" of the country.[83]

Arabization in Iraq

Saddam Hussein's Ba'ath Party had aggressive Arabization policies involving driving out many pre-Arab and non-Arab ethnic groups – mainly Kurds, Assyrians, Yezidis, Shabaks, Armenians, Turcomans, Kawliya, Circassians, and Mandeans – replacing them with Arab families.

In the 1970s, Saddam Hussein exiled between 350,000 to 650,000 Shia Iraqis of Iranian ancestry (Ajam).[84] Most of them went to Iran. Those who could prove an Iranian/Persian ancestry in Iran's court received Iranian citizenship (400,000) and some of them returned to Iraq after Saddam.[84]

During the Iran-Iraq War, the Anfal campaign destroyed many Kurdish, Assyrian and other ethnic minority villages and enclaves in North Iraq, and their inhabitants were often forcibly relocated to large cities in the hope that they would be Arabized.

This policy drove out 500,000 people in the years 1991–2003. The Baathists also pressured many of these ethnic groups to identify as Arabs, and restrictions were imposed upon their languages, cultural expression and right to self-identification.

Arabization in Syria

Since the independence of Syria in 1946, the ethnically diverse Rojava region in northern Syria suffered grave human rights violations, because all governments pursued a most brutal policy of Arabization.[85] While all non-Arab ethnic groups within Syria, such as Assyrians, Armenians, Turcomans, and Mhallami have faced pressure from Arab Nationalist policies to identify as Arabs, the most archaic of it was directed against the Kurds. In his report for the 12th session of the UN Human Rights Council titled Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights held:[86]

"Successive Syrian governments continued to adopt a policy of ethnic discrimination and national persecution against Kurds, completely depriving them of their national, democratic and human rights — an integral part of human existence. The government imposed ethnically-based programs, regulations and exclusionary measures on various aspects of Kurds' lives — political, economic, social and cultural."

The Kurdish language was not officially recognized, it had no place in public schools.[85][86][87] A decree from 1989 prohibited the use of Kurdish at the workplace as well as in marriages and other celebrations. In September 1992 came another government decree that children not be registered with Kurdish names.[88] Also businesses could not be given Kurdish names.[85][86] Books, music, videos and other material could not be published in Kurdish language.[85][87] Expressions of Kurdish identity like songs and folk dances were outlawed[86][87] and frequently prosecuted under a purpose-built criminal law against "weakening national sentiment".[89] Celebrating the Nowruz holiday was often constrained.[85][87]

In 1973, the Syrian authorities confiscated 750 square kilometers of fertile agricultural land in Al-Hasakah Governorate, which were owned and cultivated by tens of thousands of Kurdish citizens, and gave it to Arab families brought in from other provinces.[86][90] Describing the settlement policies pursued by the regime as part of the "Arab Belt programme, a Kurdish engineer in the region stated:

"The government built them homes for free, gave them weapons, seeds and fertilizer, and created agricultural banks that provided loans. From 1973 to 1975, forty-one villages were created in this strip, beginning ten kilometers west of Ras al-'Ayn. The idea was to separate Turkish and Syrian Kurds, and to force Kurds in the area to move away to the cities. Any Arab could settle in Hasakeh, but no Kurd was permitted to move and settle there."[91]

In 2007, in another such scheme in Al-Hasakah governate, 6,000 square kilometers around Al-Malikiyah were granted to Arab families, while tens of thousands of Kurdish inhabitants of the villages concerned were evicted.[86] These and other expropriations of ethnic Kurdish citizens followed a deliberate masterplan, called "Arab Belt initiative", attempting to depopulate the resource-rich Jazeera of its ethnic Kurdish inhabitants and settle ethnic Arabs there.[85]

After the Turkish-led forces had captured Afrin District in early 2018, they began to implement a resettlement policy by moving Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army fighters and Sunni Arab refugees from southern Syria into the empty homes that belonged to displaced locals.[92] The previous owners, most of them Kurds or Yazidis, were often prevented from returning to Afrin.[92] Refugees from Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, said that they were part of "an organised demographic change" which was supposed to replace the Kurdish population of Afrin with an Arab majority.[92]

De-Arabization

In the modern era, de-Arabization can refer to government policies which aim to reverse Arabization, such as the reversal of the Arabization of Kurds in northern Iraq and Mizrahi Jews in Israel.[46][93][94][95][96][97]

Historic reversions of Arabization

Norman conquest of southern Italy (999-1139)

The Muslim conquest of Sicily lasted from 827 until 902 when the Emirate of Sicily was established. It was marked by an Arab–Byzantine culture.[98] Sicily in turn was then subjected to the Norman conquest of southern Italy from 999 to 1139.[99][100] The Arab identity of Sicily came to an end latest by the mid-13th century.[98]

Reconquista (1212-1492)

The Reconquista in the Iberian Peninsula is the most notable example of a historic reversion of Arabization. The process of Arabization and Islamization was reversed as the mostly Christian kingdoms in the north of the peninsula conquered Toledo in 1212 and Cordoba in 1236.[101] Granada, the last remaining emirate on the peninsula, was conquered in January 1492.[102] The re-conquered territories were Hispanicized and Christianized, although the culture, languages and religious traditions imposed differed from those of the previous Visigothic kingdom.

Reversions in modern times

In modern times, there have been various political developments to reverse the process of Arabization. Notable among these are:

- The 1948 establishment of the State of Israel as a Jewish polity, Hebraization of Palestinian place names, use of Hebrew as an official language (with Arabic remaining co-official) and the de-Arabization of the Arabic-speaking Sephardim and Mizrahi Jews who arrived in Israel from the Arab world.[103][104]

- The 1992 establishment of a Kurdish-dominated polity in Mesopotamia as Iraqi Kurdistan.

- The 2012 establishment of a multi-ethnic Democratic Federation of Northern Syria.[105]

- Berberism, a Berber political-cultural movement of ethnic, geographic, or cultural nationalism present in Algeria, Morocco and broader North Africa including Mali. The Berberist movement is in opposition to cultural Arabization and the pan-Arabist political ideology, and is also associated with secularism.

- South Sudan's secession from Arab-led Sudan in 2011 after a bloody civil war decreased Sudan's territory by almost half. Sudan is a member of the Arab League while South Sudan did not enter membership. Arabic also is not an official language of South Sudan.

- Arabization of Malays was criticized by Sultan Ibrahim Ismail of Johor.[106] He urged the retention of Malay culture instead of introducing Arab culture.[107] He called on people to not mind unveiled women or mixed sex handshaking, and urged against using Arabic words in place of Malay words.[108] He suggested Saudi Arabia as a destination for those who wanted Arab culture.[109][110] He said that he was going to adhere to Malay culture himself.[111][112] Abdul Aziz Bari said that Islam and Arab culture are intertwined and criticized the Johor Sultan for what he said.[113] Datuk Haris Kasim, who leads the Selangor Islamic Religious Department, also criticized the Sultan for his remarks.[114]

- The Chinese government launched a campaign in 2018 to remove Arab-style domes and minarets from mosques in a campaign called "de-Arabization" and "de-Saudization".[115][116]

See also

Notes

- ^ Marium Abboud Houraney (December 2021). "The Crossroads of Identity: Linguistic Shift and the Politics of Identity in Southwest Asia and North Africa" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d Reynolds, Dwight F. (2 April 2015). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89807-2.

- ^ a b Iraq, Claims in Conflict: Reversing Ethnic Cleansing in Northern Iraq. [1]

- ^ Alexander K. McKeever (2021). "Between Kurdistan and Damascus: Kurdish Nationalism and Arab State Formation in Syria".

- ^ Hassan Mneimneh (June 2017). "Arabs, Kurds, and Amazigh: The Quest for Nationalist Fulfillment, Old and New".

- ^ Banafsheh Keynoush (2016). Saudi Arabia and Iran: Friends Or Foes?. Springer. p. 96. ISBN 9781137589392.

- ^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 496. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- ^ Nebes, Norbert, "Epigraphic South Arabian," in Uhlig, Siegbert, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 335

- ^ Leonid Kogan and Andrey Korotayev: Sayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian) // Semitic Languages. London: Routledge, 1997, pp. 157-183.

- ^ Nebes, Norbert, "Epigraphic South Arabian," in Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 335

- ^ Leonid Kogan and Andrey Korotayev: Sayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian) // Semitic Languages. London: Routledge, 1997, p[. 157-183.

- ^ "Social and political change in Bahrain since the First World War" (PDF). Durham University. 1973. pp. 46–47.

- ^ Holes, Clive (2001). Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. BRILL. pp. XXIV–XXVI. ISBN 978-90-04-10763-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Smart, J. R. (2013). Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Language And Literature. Psychology Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-7007-0411-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Houtsma, M. Th (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 5. BRILL. p. 98. ISBN 978-90-04-09791-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Holes, Clive (2001). Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. BRILL. pp. XXIX–XXX. ISBN 978-90-04-10763-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Jastrow, Otto (2002). Non-Arabic Semitic elements in the Arabic dialects of Eastern Arabia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 270–279. ISBN 978-3-447-04491-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Levinson 1995, p. 314

- ^ a b c al-Hassan 2001, p. 59.

- ^ Schulze 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Kennedy 1992, p. 292.

- ^ Barker 1966, p. 244.

- ^ a b Braida 2012, p. 183.

- ^ Peters 2003, p. 191.

- ^ Braida 2012, p. 182.

- ^ Ellenblum 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Barnard, H.; Duistermaat, Kim (1 October 2012). The History of the Peoples of the Eastern Desert. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. ISBN 978-1-931745-96-3.

- ^ Macdonald, Michael C. A. "Arabians, Arabias, and the Greeks_Contact and Perceptions". Academia.

- ^ Nehmé, Laïla; Al-Jallad, Ahmad; Nehmé, Laïla; Al-Jallad, Ahmad; Nehmé, Laïla; Al-Jallad, Ahmad, eds. (20 November 2017). To the Madbar and Back Again: Studies in the languages, archaeology, and cultures of Arabia dedicated to Michael C.A. Macdonald. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35761-7.

- ^ Vollandt, Ronny; Al-Jallad, Ahmad (1 January 2020). "Al-Jallad. 2020. The Damascus Psalm Fragment: Middle Arabic and the Legacy of Old Ḥigāzī, w. a contribution by R. Vollandt". Oriental Institute.

- ^ Berkes, Lajos (2018). "On Arabisation and Islamisation in Early Islamic Egypt. I. Prosopographic Notes on Muslim Officials". Chronique d'Égypte. 93 (186): 415–420. doi:10.1484/J.CDE.5.117663. ISSN 0009-6067.

- ^ Elfasi, M.; Hrbek, Ivan; Africa, Unesco International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of (1 January 1988). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. UNESCO. p. 243. ISBN 978-92-3-101709-4.

- ^ a b c Duri, A. A. (2012). The Historical Formation of the Arab Nation (RLE: the Arab Nation). Routledge. pp. 70–74. ISBN 978-0-415-62286-8.

- ^ a b Stearns, Peter N.; Leonard Langer, William (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged (6 ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4.

- ^ Singh, Nagendra Kr (2000). International encyclopaedia of islamic dynasties. Vol. 4: A Continuing Series. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. pp. 105–112. ISBN 978-81-261-0403-1.

- ^ "Populations Crises and Population Cycles, Claire Russell and W.M.S. Russell". Galtoninstitute.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ Hareir, Idris El; Mbaye, Ravane (1 January 2011). The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. UNESCO. p. 409. ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2.

- ^ el-Hasan, Hasan Afif (1 May 2019). Killing the Arab Spring. Algora Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-62894-349-8.

- ^ Ruffino, Giovanni (2001). Sicilia. Editori Laterza, Bari. pp. 18–20.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 103.

- ^ Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization) (1888). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17. p. 16. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Alan Moorehead, The Blue Nile, revised edition. (1972). New York: Harper and Row, p. 215

- ^ "Eritrea: The Rashaida People". Madote.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ deWaal & Flint 2006, pp. 9.

- ^ Alexander K. McKeever (2021). "Between Kurdistan and Damascus: Kurdish Nationalism and Arab State Formation in Syria".

- ^ a b Hassan Mneimneh (June 2017). "Arabs, Kurds, and Amazigh: The Quest for Nationalist Fulfillment, Old and New".

- ^ Banafsheh Keynoush (2016). Saudi Arabia and Iran: Friends Or Foes?. Springer. p. 96. ISBN 9781137589392.

- ^ Language Maintenance or Shift? An Ethnographic Investigation of the Use of Farsi among Kuwaiti Ajams: A Case Study. AbdulMohsen Dashti. Arab Journal for the Humanities. Volume 22 Issue : 87. 2004.

- ^ Dina Al-Kassim (2010). On Pain of Speech: Fantasies of the First Order and the Literary Rant. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780520945791.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip C. (7 May 2015). Historical Dictionary of Algeria. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8108-7919-5.

- ^ Daoud, Mohamed (30 June 1991). "Arabization in Tunisia: The Tug of War". Issues in Applied Linguistics. 2 (1): 7–29. doi:10.5070/L421005130.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sirles, Craig A. (1 January 1999). "Politics and Arabization: the evolution of postindependence North Africa". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (137). doi:10.1515/ijsl.1999.137.115. ISSN 0165-2516. S2CID 145218630.

- ^ Shatzmiller, Maya (29 April 2005). Nationalism and Minority Identities in Islamic Societies. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-7254-6.

- ^ James McDougall. History and the Culture of Nationalism in Algeria. Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Pp. 25.

- ^ Baldauf, Richard B.; Kaplan, Robert B. (1 January 2007). Language Planning and Policy in Africa. Multilingual Matters. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-84769-011-1.

- ^ Platteau, Jean-Philippe (6 June 2017). Islam Instrumentalized. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-107-15544-2.

- ^ Mehri, Abdelhamid (January 1972). "Arabic language takes back its place". Le Monde Diplomatique.

- ^ Benrabah, Mohamed (10 August 2010). "Language and Politics in Algeria". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 10 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1080/13537110490450773. S2CID 144307427.

- ^ Abu-Haidar, Farida. 2000. 'Arabisation in Algeria'. International Journal of Francophone Studies 3 (3): 151–163.

- ^ ordonnance n° 68-92 du 26 avril rendant obligatoire, pour les fonctionnaires et assimilés, la connaissance de la langue nationale (1968)

- ^ Benrabah, Mohamed. 2007. 'Language Maintenance and Spread: French in Algeria'. International Journal of Francophone Studies 10 (1–2): 193–215

- ^ "Algérie: Ordonnance no 96-30 du 21 décembre 1996". www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ article 3bis in the 2002 constitutional revision

- ^ loi du 25 fevrier 2008 http://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/afrique/algerie_loi-diverses.htm#Loi_n°_08-09_du_25_février_2008_portant_code_de_procédure_civile_et_administrative_

- ^ Cellier, Catherine (2015). "The languages of Oman". Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Kumzari, the Omani language on the verge of extinction". 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Last stand of a hybrid language from Oman's seafaring past". 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Kumzari". Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Al Jahdhami, Said (October 2016). "Minority Languages in Oman". Journal of the Association for Anglo-American Studies. 4.

- ^ "Hobyót in the Language Cloud". Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Morris, M. 2007. "The pre-literate, non-Arabic languages of Oman and Yemen. Archived 2015-03-08 at the Wayback Machine" Lecture conducted from Anglo-Omani and British-Yemeni Societies.

- ^ Peterson, J.E. "Oman's Diverse Society: Southern Oman." In: Middle East Journal 58.2, 254-269.

- ^ Swiggers, P. 1981. "A Phonological Analysis of the Ḥarsūsi Consonants." In: Arabica 28.2/3, 358-361.

- ^ United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), "Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger", 2010.

- ^ "النقوش والكتابات الصخرية بسلطنة عمان.. إرث قديم وشواهد على التاريخ". 25 October 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Shehri: A Native Omani Language Under Threat". 16 September 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Hall, Joe. "The National Newspaper". Vol. 12, no. 220. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "MSAL Project Information" (PDF). University of Salford. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Redouane, Rabia (May 1998). "Arabisation in the Moroccan Educational System: Problems and Prospects". Language, Culture and Curriculum. 11 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1080/07908319808666550. ISSN 0790-8318.

- ^ a b c d e f Daoud, Mohamed (30 June 1991). Arabization in Tunisia: The Tug of War. eScholarship, University of California. OCLC 1022151126.

- ^ a b Bechtold, Peter K. (2015). "Languages" (PDF). In Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Sudan: a country study (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-8444-0750-0.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Though published in 2015, this work covers events in the whole of Sudan (including present-day South Sudan) until the 2011 secession of South Sudan.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Though published in 2015, this work covers events in the whole of Sudan (including present-day South Sudan) until the 2011 secession of South Sudan.

- ^ "Mauritania Fights to End Racism". www.npr.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010.

- ^ Alicia Koch, Patrick K. Johnsson (8 April 2010). "Mauritania: Marginalised Black populations fight against Arabisation - Afrik-news.com: Africa news, Maghreb news - The African daily newspaper". Afrik-news.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Hamshahri Newspaper (In Persian)". hamshahri.org. Retrieved 12 November 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch. 1996.

- ^ a b c d e f "Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria, Report for the 12th session of the UN Human Rights Council" (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d Tejel, Jordi; Welle, Jane (2009). Syria's kurds history, politics and society (PDF) (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. X. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Gunter, Michael M. (2014). Out of Nowhere: The Kurds of Syria in Peace and War. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-84904-435-6.

- ^ "HRW World Report 2010". Human Rights Watch. 2010.

- ^ "A murder stirs Kurds in Syria". The Christian Science Monitor. 16 June 2005.

- ^ "Syria: The Silenced Kurds". Human Rights Watch. 1 October 1996. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Patrick Cockburn (18 April 2018). "Yazidis who suffered under Isis face forced conversion to Islam amid fresh persecution in Afrin". The Independent. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Ahmed S. Hashim (2011). Insurgency and Counter-Insurgency in Iraq. Cornell University Press. p. 362. ISBN 9780801459986.

- ^ W. Andrew Terrill (2010). Lessons of the Iraqi De-Ba'athification Program for Iraq's Future and the Arab Revolutions. Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. p. 16. ISBN 9781584875277.

- ^ Uri Ram (2017). Israeli Sociology: Text in Context. Springer. p. 130. ISBN 9783319593272.

- ^ Anna Bernard (2013). Debating Orientalism. Springer. p. 110. ISBN 9781137341112.

- ^ Naphtaly Shem-Tov (2021). Israeli Theatre: Mizrahi Jews and Self-Representation. Routledge. ISBN 9781351009065.

- ^ a b Brown, Gordon S. (2015) [2003]. "Sicily". The Norman Conquest of Southern Italy and Sicily. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 103–113. ISBN 978-0-7864-5127-2. LCCN 2002153822.

- ^ Matthew, Donald (2012) [1992]. "Part I: The Normans and the monarchy – Southern Italy and the Normans before the creation of the monarchy". The Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks. Cambridge and New York City: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–19. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139167741.004. ISBN 9781139167741.

- ^ Deanesly, Margaret (2019). "The Later Merovingians". A History of Early Medieval Europe: From 476–911. Routledge Library Editions: The Medieval World (1st ed.). London and New York City: Routledge. pp. 244–245. ISBN 9780367184582.

- ^ Carr, Karen (3 August 2017). "The Reconquista - Medieval Spain". Quatr.us Study Guides. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "The Conquest of Granada". www.spanishwars.net. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ Yehouda A. Shenhav (2006). The Arab Jews: A Postcolonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity. Stanford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8047-5296-1.

- ^ Basheer K. Nijim [in Arabic]; Bishara Muammar (1984). Toward the De-Arabization of Palestine/Israel, 1945-1977. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8403-3299-8.

- ^ "After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools". Al-Monitor. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "Stop aping Arabs, Johor Sultan tells Malays". Malay Mail Online. KUALA LUMPUR. 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Stop trying to be like Arabs, Johor ruler tells Malays". The Straits Times. JOHOR BARU. 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Johor Sultan Says Be Malay Not Arab". Asia Sentinel. 28 March 2016.

- ^ Zainuddin, Abdul Mursyid (24 March 2016). "Berhenti Cuba Jadi 'Seperti Arab' – Sultan Johor". Suara TV. JOHOR BAHRU. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017.

- ^ "Sultan Johor Ajak Malaysia Jaga Tradisi Melayu, Bukan Arab". TEMPO.CO. TEMPO.CO , Kuala Lumpu. 24 March 2016.

- ^ wong, chun wai (24 March 2016). "Stop trying to be like Arabs, Ruler advises Malays". The Star Online. JOHOR BARU.

- ^ "Stop aping Arabs, Johor Sultan tells Malays". TODAYonline. KUALA LUMPUR. 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Arab culture integral to Islam, Johor sultan advised". malaysiakini. 24 March 2016.

- ^ Irsyad, Arief (7 April 2016). "Is "Arabisation" A Threat To The Malay Identity As Claimed By The Johor Sultan? Here's What Some Malays Have To Say". Malaysian Digest. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016.

- ^ "China's new campaign to make Muslims devoted to the state rather than Islam". Los Angeles Times. 20 November 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Canada, Immigration and Refugee Board of (14 October 2022). "China: Situation of Hui Muslims and their treatment by society and authorities; state protection (2020–September 2022) [CHN201172.E]". Retrieved 14 June 2023.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 103.

This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States.- al-Bagdadi, Nadia (2008). "Syria". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W.; Barrett, David B. (eds.). The Encyclodedia of Christianity. Vol. 5: Si-Z. Eerdmans.Brill. ISBN 978-0-802-82417-2.

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001). "Factors Behind the Rise of Islamic Science". In al-Hassan, Ahmad Y.; Ahmed, Maqbul; Iskandar, Albert Z. (eds.). The Different Aspects of Islamic Culture. Vol. 4:Science and Technology in Islam. Part 1: The exact and Natural Sciences. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. ISBN 978-9-231-03830-3.

- Arnold, Werner (2007). "Arabic Grammatical Borrowing in Western Neo-Aramaic". In Matras, Yaron; Sakel, Jeanette (eds.). Grammatical Borrowing in Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Empirical Approaches to Language Typology. Vol. 38. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-19628-3. ISSN 0933-761X.

- Barker, John W. (1966). Justinian and the Later Roman Empire. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-03944-8.

- Braida, Emanuela (2012). "Garshuni Manuscripts and Garshuni Notes in Syriac Manuscripts". Parole de l'Orient. 37. Holy Spirit University of Kaslik. ISSN 0258-8331.

- Brock, Sebastian (2010). "The Syrian Orthodox Church in the modern Middle East". In O'Mahony, Anthony; Loosley, Emma (eds.). Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-19371-3.

- Correll, Christoph (1987). "Ma'lūlā. 2. The Language". In Bosworth, Clifford Edmund; van Donzel, Emericus Joannes; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Dijkema, F. Th.; Nurit, Mme S. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. VI. Fascicules 103-104 (Malḥūn-Mānd) (New ed.). Brill. OCLC 655961825.

- deWaal, Alex; Flint, Julie (2006). Darfur: a short history of a long war. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-697-1.

- Ellenblum, Ronnie (2006). Crusader Castles and Modern Histories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86083-3.

- Held, Colbert C.; Cummings, John Thomas (2018) [2016]. Middle East Patterns, Student Economy Edition: Places, People, and Politics. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-96199-1.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1992). "The Impact of Muslim Rule on the Pattern of Rural Settlement in Syria". In Canivet, Pierre; Rey-Coquais, Jean-paul (eds.). La Syrie de Byzance à l'Islam VIIe-VIIIe Siècles. Damascus, Institut Français du Proche Orient. OCLC 604181534.

- Levinson, David (1995). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Africa and the Middle East. G.K. Hall. ISBN 978-0-8161-1815-1. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- Peters, Francis Edward (2003). Islam: A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-400-82548-6.

- Schulze, Wolfgang (2010). "Symbolism on the Syrian Standing Caliph Copper Coins: A Contribution to the Discussion". In Oddy, Andrew (ed.). Coinage and History in the Seventh Century Near East: Proceedings of the 12th Seventh Century Syrian Numismatic Round Table Held at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge on 4th and 5th April 2009. Archetype Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-1-904-98262-3.

- Troupeau, Gérard (1987). "Ma'lūlā. 1. The Locality". In Bosworth, Clifford Edmund; van Donzel, Emericus Joannes; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Dijkema, F. Th.; Nurit, Mme S. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. VI. Fascicules 103-104 (Malḥūn-Mānd) (New ed.). Brill. OCLC 655961825.

External links

- Genetic Evidence for the Expansion of Arabian Tribes into the Southern Levant and North Africa

- Bossut, Camille Alexandra. Arabization in Algeria : language ideology in elite discourse, 1962-1991 (Abstract) - PhD thesis, University of Texas at Austin, May 2016.