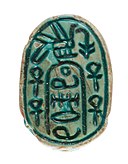

Anra scarab

Anra scarabs are scarab seals dating to the Second Intermediate Period found in the Levant, Egypt and Nubia.[1] Anra scarabs are identified by an undeciphered and variable sequence of Egyptian hieroglyphs on the base of the scarab which always include the symbols a, n and r.[2] As anra scarabs have overwhelmingly been found in Palestine (~80%), it has been suggested it was marketed by the contemporaneous 15th Dynasty for the Canaanites.[3]: 277

The artifacts have tentatively been associated with the gods El and Ra, who were identified with each other in the Ramesside Period.

Meaning

| ||

| ʿ-n-r-ʿ anra in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Era: 2nd Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BC) | ||

Scarab seals were produced in vast numbers for many centuries and many thousands have survived. They were generally intended to be worn or carried by the living. They were typically carved or moulded in the form of a scarab beetle (usually identified as Scarabaeus sacer) with varying degrees of naturalism but usually at least indicating the head, wing case and legs but with a flat base. The base was usually inscribed with designs or hieroglyphs to form an impression seal.

Whilst some consider the anra sequence on the base of scarabs to be nonsense and random,[4]: 18 others consider it to have a more specific meaning.[5] The sequence would have been considered important as it was included on the royal name scarabs of the pharaoh Senusret I and on a cylinder seal of Hyksos king Khyan. It was also reused by Ramesses II.[6]

Some scholars consider the anra scarabs were used only for its amuletic qualities, and that the seals found in Palestine were an adapted Canaanite form of an Egyptian funerary custom, transmitted through Asiatics living in the Nile Delta.[7]: 11 Murray argued that the skill and subsequent cost of producing anra scarabs would not have been spent haphazardly on ignorant copies of misunderstood inscriptions, and must have been important and relayed meaning to the wearer. The Canaanites often incorporated Egyptian iconography into their designs, but in such a manner to suggest that they understood what they were using.[8]

Religious

Fiona Richards proposed that the added ḥtp symbol to the anra sequence found on scarabs equates to the Canaanite deity El. As this anra sequence is confined to Palestine, it could mean it was deliberately marketed for them specifically.[9] As the princes of Byblos adopted Egyptian titles and the use of Egyptian symbols permeated Syrian glyptic, the use of El by the Egyptians would not seem out of place if considered at a time of heightened socio-political ties.[10]

It has been suggested that when the inscriptions are presented in their full, unshortened form, it equates to the god Ra. El is equated to Ra, and they are identified as one and the same in the Ramesside Period.[11]: 10–11 Hornung and Staehelin associated the formula with a spell connected to Ra.[12]

Secret

Schulman interprets the sequence as texts written in a secret, enigmatic manner, comprehensible only to the initiate, which served to increase and enhance the potency of the charm.[13][14]

Protection

Due to associations with royal emblems (75% of all anra scarabs are associated with signs and symbols of Egyptian royalty), Murray proposed that it could be possible that these scarabs were intended to "commemorate the solemn ceremony of the giving of the Re-name to the king, and to protect the name where given."[15][9]

Magic

It has been put forward that the inscriptions are associated with the "abracadabra" magical words that exist in Egyptian magical texts.[16]

Good luck

Daphna Ben-Tor argues that the anra sequence did not have a specific meaning, but was rather treated as a generic group of good luck symbols with Egyptian prestige value.[17]

Blessing

The anra sequence could have its origins in the Neferzeichen (royal power or blessing) patterns of the Middle Kingdom.[18][1]: 26

King

Weill believed that it was associated with a king of the same name.[19]

Location

Anra scarabs have been found at archaeological sites throughout the Levant, Egypt and Nubia. Notable sites include: Ras Shamra, Byblos, Beth-shan, Pella, Memphis, Shechem, Gezer, Shiloh, Amman, Gerar, Tell El-Dab'a, Esna, Debeira, Mirgissa, Jericho and Rishon.[9]: 299 They have been found amongst precious objects such as gold, gemstones and weapons at a higher rate than other scarabs found in tombs,[9]: 275, 268 and they have been discovered in the archaeological remains of palaces, temples, sanctuaries and residences of high ranking officials.[9]

In Egypt and Nubia, the anra scarabs that have been found stay closer to the original three sign sequence without the supplementary Egyptian iconography more prevalent in the Levant.[20]

Gaza

Gezer

Sedment

See also

References

- ^ a b Richards, Fiona (1998). The Anra scarab : an archaeological and historical approach. p. 209. doi:10.30861/9781841712178. hdl:1842/26878. ISBN 9781841712178. S2CID 127185087.

- ^ Levant: The Journal of the Council for British Research in the Levant. British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. 1994. p. 234.

- ^ Richards, Fiona V. (1998). The Anra scarab: an archaeological and historical approach. p. 11-298. doi:10.30861/9781841712178. hdl:1842/26878. ISBN 9781841712178. S2CID 127185087.

Eighty percent of all Anra scarabs were found in Palestine, it would appear that this scarab was marketed specifically by the 15th dynasty for the Palestinian market

- ^ Giveon, Raphael (1985). Egyptian scarabs from Western Asia from the collections of the British Museum. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag, Freiburg (CH). ISBN 3-72780-332-0.

- ^ Richards, Fiona V. (1992). Scarab Seals from a Middle to Late Bronze Age Tomb at Pella in Jordan. Saint-Paul. ISBN 978-3-525-53751-0.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Daphna (2017). "Ramesside Scarabs Simulating Middle Bronze Age Canaanite Prototypes". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 27: 195–218. doi:10.1553/AEundL27s195. ISSN 1015-5104. JSTOR 26524901.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Daphna (1994). "The Historical Implications of Middle Kingdom Scarabs Found in Palestine Bearing Private Names and Titles of Officials". BASOR. 294 (294): 7–22. doi:10.2307/1357151. JSTOR 1357151. S2CID 163810843.

- ^ Brummett, Palmira Johnson; Edgar, Robert R.; Hackett, Neil J.; Jewsbury, George F.; Taylor, Alastair M. (2002). Civilization Past & Present. Longman. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-321-09090-4.

- ^ a b c d e Richards, Fiona V. (1998). The Anra scarab: an archaeological and historical approach. p. 277. doi:10.30861/9781841712178. hdl:1842/26878. ISBN 9781841712178. S2CID 127185087.

- ^ Jáuregui, Miguel Herrero de; Cristóbal, Ana Isabel Jiménez San; Martínez, Eugenio R. Luján; Hernández, Raquel Martín; Álvarez, Marco Antonio Santamaría; Tovar, Sofía Torallas (2011-12-08). Tracing Orpheus: Studies of Orphic Fragments. Walter de Gruyter. p. 100. ISBN 978-3-11-026053-3.

- ^ Pritchard, James B., ed. (1955). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (2 ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ 1976: 51-52

- ^ Schulman, Alan R. (1975). "The Ossimo Scarab Reconsidered". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 12: 15–18. doi:10.2307/40000004. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000004.

- ^ SCHULMAN, ALAN R. (1978). "THE KING'S SON IN THE WÂDI NAṬRŪN". The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists. 15 (1/2): 103–113. ISSN 0003-1186. JSTOR 24518760.

- ^ Murray, M. A. (1949-10-01). "Some Canaanite Scarabs". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 81 (2): 96. doi:10.1179/peq.1949.81.2.92. ISSN 0031-0328.

- ^ Schenkel, Wolfgang (1980). "Hornung, Erik u. Elisabeth Staehelin, Skarabäen und andere Siegelamulette aus Basler Sammlungen, Mainz 1976". Orientalistische Literaturzeitung. doi:10.11588/propylaeumdok.00003370. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Daphna (2009-01-01). "Pseudo hieroglyphs on Canaanite scarabs". Non-Textual Marking Systems, Writing and Pseudo Script: 82.

- ^ Ameri, Marta; Costello, Sarah Kielt; Jamison, Gregg; Scott, Sarah Jarmer (2018-05-03). Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-17351-3.

- ^ 1918: 193

- ^ Richards 1996 p. 167