Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan

The Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan in 1896–1899 was a reconquest of territory lost by the Khedives of Egypt in 1884–1885 during the Mahdist War. The British had failed to organise an orderly withdrawal of the Egyptian Army from Sudan, and the defeat at Khartoum left only Suakin and Equatoria under Egyptian control after 1885. The conquest of 1896–1899 defeated and destroyed the Mahdist State and re-established Anglo-Egyptian rule, which remained until Sudan became independent in 1956.

Preliminaries

There was a considerable body of opinion in Britain in favour of retaking Sudan after 1885, largely to "avenge Gordon". However, Lord Cromer, the British consul-general in Egypt, had been the architect of the British withdrawal after the Mahdist uprising. He remained sure that Egypt needed to recover its financial position before any invasion could be contemplated. "Sudan is worth a good deal to Egypt," he said, "but it is not worth bankruptcy and extremely oppressive taxation."[1] He felt it was necessary to avoid "being driven into premature action by the small but influential section of public opinion which persistently and strenuously advocated the cause of immediate reconquest." As late as 15 November 1895 he had been assured by the British government that it had no plans to invade Sudan.[2]

By 1896, however, it was clear to Prime Minister Salisbury that the interests of other powers in Sudan could not be contained by diplomacy alone – France, Italy and Germany all had designs on the region that could only be contained by re-establishing Anglo-Egyptian rule.[3][4] The catastrophic defeat of the Italians by Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia at the Battle of Adwa in March 1896 also raised the possibility of an anti-European alliance between Menelik and the Khalifa of Sudan.[5] After Adwa the Italian government appealed to Britain to create some kind of military diversion to prevent Mahdist forces from attacking their isolated garrison at Kassala, and on 12 March the British cabinet authorised an advance on Dongola for this purpose.[2] Salisbury was also at pains to reassure the French government that Britain intended to proceed no further than Dongola, so as to forestall any move by the French to advance some claim of their own on part of Sudan.[6] The French government had in fact just dispatched Jean-Baptiste Marchand up the Congo River with the stated aim of reaching Fashoda on the White Nile and claiming it for France. This encouraged the British to attempt the full-scale defeat of the Mahdist State and the restoration of Anglo-Egyptian rule, rather than just providing a military diversion as Italy had requested.[7]

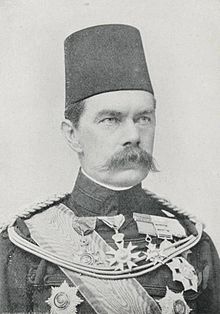

Lord Salisbury then ordered the Sirdar, Brigadier Herbert Kitchener to make preparations for an advance up the Nile. As Governor-General of Suakin from 1886 to 1888, Kitchener had held off the Mahdist forces under Osman Digna from the Red Sea coast,[8] but he had never commanded a large army in battle.[9] Kitchener took a methodical, unhurried approach to recovering Sudan. In the first year his objective was to recover Dongola; in the second, to construct a new railway from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad; in the third, to retake Khartoum.[5]

Kitchener's forces

The Egyptian army mobilised and by 4 June 1896 Kitchener had assembled a force of 9,000 men, consisting of ten infantry battalions, fifteen cavalry and camel corps squadrons, and three artillery batteries. All the soldiers were Sudanese or Egyptian, with the exception of a few hundred men from the North Staffordshire Regiment and some Maxim gunners.[10] The use of British troops was kept to a minimum and Sudanese troops were used wherever possible, partly because they were cheaper, and partly because they could survive the extreme conditions of campaigning in Sudan which Europeans often could not.[2] To maximise the number of Sudanese troops deployed for the invasion, the Sudanese garrison was withdrawn from Suakin on the Red Sea and replaced with Indian soldiers. The Indians arrived in Suakin on 30 May, releasing the Xth Egyptian and Sudanese battalions for the Dongola expedition.[11]

The Egyptian army in the 1880s was consciously trying to distance itself from the times of Muhammad Ali, when Sudanese men had been captured, enslaved, shipped to Egypt and enlisted. Nevertheless, on the eve of the 1896 invasion the manumission status and precise recruitment conditions of many Sudanese soldiers in the Egyptian army was unclear. Egyptian conscripts were required to serve six years in the army, whereas Sudanese soldiers enlisted before 1903 were signed up for life, or until medically unfit to serve.[12] While no official requirement existed for the practice, it is clear that in many instances at least, new Sudanese recruits into the Egyptian army were branded by their British officers, to help identify deserters and those discharged seeking to re-enlist.[13]

Sudan Military Railroad

Kitchener placed great importance on transport and communications. Reliance on river transport, and the vagaries of the Nile flooding, had reduced Garnet Wolseley's Nile Expedition to failure in 1885, and Kitchener was determined not to let that happen again. This required the building of new railways to support his invasion forces.

The first phase of railway building followed the initial campaign up the Nile to the supply base at Akasha and then on southward towards Kerma. This bypassed the second cataract of the Nile and thereby ensured that supplies could reach Dongola all year round, whether the Nile was in flood or not. The railway extended as far as Akasha on 26 June and as far as Kosheh on 4 August 1896. A dockyard was constructed and three entirely new gunboats, larger than the Egyptian river boats already deployed, were brought in sections by rail, and then assembled on the river. Each carried one 12-pounder forward-firing gun, two 6-pounders midships and four Maxim guns.[14] At the end of August 1896 storms washed away a 12-mile section of the railway as preparations were being made to advance on Dongola. Kitchener personally supervised 5,000 men who worked night and day to ensure it was rebuilt in a week.[9] After Dongola was taken, this line was extended south to Kerma.

Building the 225-mile-long railway from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad was a much more ambitious undertaking. General opinion held the construction of such a railway to be impossible, but Kitchener commissioned Percy Girouard, who had worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway to undertake the project. Work began on the line on 1 January 1897, but little progress made until the line to Kerma was completed in May, when work began in earnest. By 23 July, 103 miles had been laid, but the project was continually under attack from Mahdists based in Abu Hamad. Kitchener ordered General Archibald Hunter to advance from Merawi and eliminate the threat. Hunter's forces travelled 146 miles in eight days and took Abu Hamad on 7 August 1897. Work could then proceed, and the railway eventually reached Abu Hamad on 31 October.[15] (see also Battle of Abu Hamed)

There were major problems in undertaking a major construction project in a waterless desert, but Kitchener had the good fortune to locate two sources and had wells dug to provide the water needed. To keep within the tight budget limits set by Lord Cromer, Kitchener ordered that the first section of the railway should be built from reused materials scavenged from the Khedive Ismail's derelict railway from the 1870s. In another economy measure, Kitchener borrowed steam engines from South Africa to work on the line.[16] Kitchener's workforce were soldiers and convicts, and he worked them very hard, sleeping just four hours each night, and doing physical labour himself. As the railway progressed in the extreme conditions of the desert, the number of deaths among his men increased, and Kitchener blamed his subordinates for them.[17]

The Sudan Military Railway was later described as the deadliest weapon ever used against Mahdism. The 230 miles of railway reduced the journey time between Wadi Halfa and Abu Hamad from 18 days by camel and steamer to 24 hours by train, all year round, regardless of the season and the flooding of the Nile. He also had 630 miles of telegraph cable laid, and 19 telegraph offices built along the railway, which were soon handling up to 277 messages per day.[18]

Later, when the line was extended towards Atbara, Kitchener was able to transport three heavily armed gunboats in sections to be reassembled at Abadieh, enabling him to patrol and reconnoitre the river up to the sixth cataract.[9]

Campaign of 1896

The Egyptian army moved swiftly to the border at Wadi Halfa and began moving south on 18 March to take Akasha, a village which was to be the base for the expedition. Akasha was deserted when they entered on 20 March[19] and Kitchener devoted the next two months to building up his forces and supplies ready for the next advance.

Apart from occasional skirmishing, the first serious contact with Mahdist forces took place in early June at the village of Farka. The village was a Mahdist strongpoint some way upriver from Akasha; its commanders, Hammuda and Osman Azraq, led around 3,000 soldiers and had evidently decided to hold his ground rather than withdraw as the Egyptian army advanced.[19] At dawn on 7 June, two Egyptian columns attacked the village from north and south, killing 800 Mahdist soldiers, with others plunging naked into the Nile to make their escape. This left the road to Dongola clear, but despite advice to move rapidly and take it, Kitchener adhered to his usual cautious and carefully prepared approach.

Kitchener took time to build up supplies at Kosheh, and brought his gunboats south through the second cataract of the Nile ready for an assault on Dongola.[20] The Egyptian river navy consisted of the gunboats Tamai, El Teb, Metemma and Abu Klea as well as the steamers Kaibar, Dal and Akasha. They had been used to patrol the river between Wadi Halfa and Aswan, and were now pressed into service as part of the invasion force. They had to wait however for the Nile to flood before they could navigate over the second cataract, and in 1896 the flood was unusually late, meaning that the first boat could not pass until 14 August. Each of the seven boats had to be physically hauled up over the cataract by two thousand men, at the rate of one boat per day.[21] To this force were added the three new gunboats brought round the cataract by rail and assembled on the river at Kosheh.

Dongola was defended by a substantial Mahdist force under the command of Wad Bishara, consisting of 900 jihadiyya, 800 Baqqara Arabs, 2,800 spearmen, 450 camel and 650 horse cavalry. Kitchener was unable to advance on Dongola immediately after the Battle of Farka because not long afterwards, cholera broke out in the Egyptian camp, and killed over 900 men in July and early August 1896.[22] With the summer of 1896 marked by disease and severe weather, Kitchener's columns, supported by gunboats on the Nile, finally began to advance up the Nile towards Kerma, at the third cataract, where Wad Bishara had established a forward position. Instead of defending it however he moved his forces across the river so that as the Egyptian gunboats came upstream he was able to concentrate heavy fire on them. On 19 September the gunboats made several runs at the Mahdist positions, firing at their trenches, but the fire returned was too intense for them to maintain their position safely. Kitchener therefore ordered them to simply steam on, past the Mahdist position, towards Dongola. Seeing them proceed, Wad Bishara withdrew his forces to Dongola. On 20 September the gunboats exchanged fire with the town's defenders and on 23 Kitchener's main force reached the town.[23] Wad Bishara, seeing the overwhelming size of the Egyptian force, and unnerved by several days of bombardment by the gunboats, withdrew. The town was occupied, as were Merowe and Korti.[5] Total Egyptian losses for the capture of Dongola were one killed and 25 wounded. Kitchener was promoted to Major-General.[24]

Campaign of 1897

The fall of Dongola was a shock to the Khalifa and his followers in Omdurman, as it immediately placed their capital under threat. They thought it was likely that Kitchener would attack by striking across the desert from Korti to Metemma, as the Nile Expedition had done in 1885. The Khalifa therefore directed Osman Azraq to hold Abu Klea and Wad Bishara to hold Metemma with a force of Ja'alin. He also ordered Osman Digna in eastern Sudan and his commanders in Kordofan and other regions to bring their forces in to Omdurman, strengthening its defences with some 150,000 additional fighters. This concentrated the Mahdist forces in the capital and the northern approaches, down the Nile to Berber. Aware that Kitchener had a substantial river force which had by now passed up the second cataract into the Dongola Reach, the Khalifa sought to prevent it steaming further upriver by blocking the sixth cataract at the Shabluka gorge, which was the last river obstacle before Omdurman. To this end forts were built at the northern end of the gorge, and the paddle-steamer Bordein carried guns and supplies upriver.[25]

Kitchener did not advance on Omdurman after taking Dongola, and by May 1897 the Khalifa's forces from Kordofan had increased the size of his forces to the point where he felt able to take a more offensive stance. He therefore decided to advance the Kordofan army down the river to Metemma, in Ja'alin country. The loyalty of the Ja'alin to the Mahdist state had weakened as the Egyptian army advanced, and they were particularly unwilling to have a large army quartered with them. Their chief, Abdallah wad Saad, therefore wrote to Kitchener on 24 June, pledging the loyalty of his people to Egypt and asking for men and weapons to assist them against the Khalifa. Kitchener sent 1,100 Remington rifles and ammunition, but they did not arrive in time to help the Ja'alin defend Metemma from the Khalifa's army, which arrived on 30 June and stormed the town, killing wad Saad and driving his surviving followers away.[26]

For Kitchener, much of 1897 was taken up extending the railway to Abu Hamed. The town was taken on 7 August and the railway reached it on 31 October. Even before this river strongpoint was secured, Kitchener ordered his gunboats to proceed upriver past the fourth cataract. With help from the local Shayqiyya, the attempt began on 4 August, but the current was so strong that the gunboat El Teb could not be hauled over the rapids, and capsized. However the Metemma made the passage safely on 13 August, the Tamai on 14, and on 19 and 20 August the new gunboats Zafir, Fateh and Nasir also passed the cataract.[27]

The sudden advance of the river force and uncertainty about whether he would be reinforced by the Kordofan Army prompted the Mahdist commander in Berber, Zeki Osman, to abandon the town on 24 August, and it was occupied by the Egyptians on 5 September.[15] The overland route from Berber to Suakin was now reopened, meaning that the Egyptian army could be reinforced and resupplied by river, by rail and by sea. As the Red Sea area returned its loyalty to Egypt, an Egyptian force also marched from Suakin to retake Kassala, which had been temporarily occupied by the Italians since 1893. The Italians ceded control on Christmas Day.[28]

For the remainder of the year Kitchener extended the railway line forward from Abu Hamad, built up his forces in Berber, and fortified the north bank of the confluence with the Atbarah River. Meanwhile, the Khalifa strengthened the defences of Omdurman and Metemma and prepared an attack on the Egyptian positions while the river was low and the gunboats could neither retreat below the fifth cataract nor advance above the sixth.[29]

Campaign of 1898

To be sure he had the necessary strength to defeat the Mahdist forces in their heartland, Kitchener brought up reinforcements from the British Army, and a brigade under Major General William F. Gatacre arrived in Sudan at the end of January 1898. The Warwicks, Lincolns and Cameron Highlanders had to march the last thirty miles as the railway had not yet caught up with the front line.[30] Skirmishes took place in the early Spring, as the Mahdist forces made an attempt in March to outflank Kitchener by crossing the Atbara, but they were outmaneuvered; the Egyptians steamed upstream and raided Shendi. Eventually, at dawn on 8 April, the Anglo-Egyptians mounted a full frontal assault on the forces of Osman Digna with three infantry brigades, holding one in reserve. Fighting lasted less than an hour and concluded with 81 Anglo-Egyptian soldiers killed and 478 wounded, to over 3,000 Mahdist troops dead.

The Khalifa's forces then withdrew to Omdurman, abandoning Metemma and the sixth cataract so that the Egyptian army could pass unmolested. Preparations then continued for an advance on Omdurman. The railway was extended southwards and additional reinforcements arrived. By mid-August 1898 Kitchener had at his command 25,800 troops, composed of the British Division under Major-General Gatacre, with two British infantry brigades; and the Egyptian Division with four Egyptian brigades under Major General Hunter. The gunboat Zafir, proceeding upriver, foundered and sank opposite Metemma on 28 August. Meanwhile, the Khalifa attempted to lay a mine in the river to prevent the Egyptian boats from bombarding Omdurman, but this resulted in the mine-laying ship Ismailia being blown up with its own mine.[31]

The final advance on Omdurman began on 28 August 1898.[32]

Battle of Omdurman

The defeat of the Khalifah's forces at Omdurman marked the effective end of the Mahdist State, though not the end of campaigning. Over 11,000 Mahdist fighters died at Omdurman, and another 16,000 were seriously wounded. On the British and Egyptian side there were fewer than fifty dead and several hundred wounded.[33] The Khalifa retreated into the city of Omdurman but could not rally his followers to defend it. Instead they scattered across the plains to the west and escaped. Kitchener entered the city, which formally surrendered without further fighting, and the Khalifa escaped before he could be captured.[34]

British gunboats bombarded Omdurman before and during the battle, damaging part of the city walls and the tomb of the Mahdi, although destruction was not very widespread.[35] There is some controversy about the conduct of Kitchener and his troops during and immediately following the battle. In February 1899, Kitchener responded to criticisms by categorically denying that he had ordered or permitted the Mahdist wounded in the battlefield to be massacred by his troops; that Omdurman had been looted; and that civilian fugitives in the city had been deliberately fired on. There is no evidence for the last accusation, but some foundation for the others.[36] In The River War, Winston Churchill was critical of Kitchener's conduct, and in private correspondence he said that 'the victory at Omdurman was disgraced by the inhuman slaughter of the wounded and that Kitchener was responsible for this.' [37] The Mahdi's tomb, the largest building in Omdurman, had already been looted when Kitchener gave the order for it to be blown up.[38] Kitchener ordered that the Mahdi's remains be dumped in the Nile. He considered and discussed keeping his skull, either as some kind of trophy or as a medical exhibit at the Royal College of Surgeons. Eventually however the head was buried, although anecdotes about its having been turned into an inkpot or a drinking vessel continue to circulate even today.[39][40]

Final campaigns

A force under Colonel Parsons was sent from Kassala to Al Qadarif which was retaken from Mahdist forces on 22 September. A flotilla of two boats under General Hunter was sent up the Blue Nile on 19 September to plant flags and establish garrisons wherever seemed expedient. They planted the Egyptian and British flags at Er Roseires on 30 September, and at Sennar on the return journey. Gallabat was reoccupied on 7 December, although the two Ethiopian flags that had been raised there after the Mahdist evacuation were left flying pending instructions from Cairo. Despite the easy recovery of these key towns there remained a great deal of fear and confusion in the countryside across the Jezirah, where bands of Mahdist supporters continued to roam, pillaging and killing for several months after the fall of Omdurman.[41] Once control was established in the Jazirah and eastern Sudan, the recovery of Kordofan remained a major military challenge.

On 12 July 1898 Marchand had reached Fashoda and raised the French flag. Kitchener hurried south from Khartoum with his five gunboats, and reached Fashoda on 18 September. Careful diplomacy on both men's part ensured that French claims were not pressed and Anglo-Egyptian control was reasserted.[42] (see also Fashoda Incident)

On 24 November 1899 Colonel Sir Reginald Wingate cornered the Khalifah and 5,000 followers southwest of Kosti.[42] In the ensuing battle the Khalifah was killed along with about 1,000 of his men. Osman Digna was captured, but escaped again. (see also Battle of Umm Diwaykarat) Al Ubayyid was not taken until December 1899, by which it had already been abandoned. In December 1899 Wingate succeeded Kitchener as Sirdar and Governor-General of Sudan when Kitchener departed for South Africa.

The newly established Anglo-Egyptian government in Khartoum did not attempt to reconquer the far western territory of Darfur, which the Egyptians had held only briefly between 1875 and the surrender of Slatin Pasha in 1883. Instead, they recognised the rule of the last Keira Sultan, Ali Dinar, grandson of Muhammad al-Fadl, and did not establish control over Darfur until 1913.[41] (see also Anglo-Egyptian Darfur Expedition)

Osman Digna was not recaptured until 1900.[41]

See also

References

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 p. 241 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c Edward M. Spiers, Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised, Routledge, 2013 p. 2 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Robert Collins, The British in the Sudan, 1898–1956: The Sweetness and the Sorrow, Springer, 1984 p. 8 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Harold E. Raugh Jr., British Military Operations in Egypt and the Sudan: A Selected Bibliography, Scarecrow Press, 2008 p. xiv [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c Harold E. Raugh Jr., British Military Operations in Egypt and the Sudan: A Selected Bibliography, Scarecrow Press, 2008 p. xxviii [ISBN missing]

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 p. 240 [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Marchand and the Race for Fashoda | Military Sun Helmets". www.militarysunhelmets.com. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 p. 247 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c Edward M. Spiers, Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised, Routledge, 2013 p. 3 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Harold E. Raugh Jr., British Military Operations in Egypt and the Sudan: A Selected Bibliography, Scarecrow Press, 2008 p. xxxviii [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 1 pp. 202–204 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Ronald M. Lamothe, Slaves of Fortune: Sudanese Soldiers and the River War, 1896–1898, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2011 p. 32 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Ronald M. Lamothe, Slaves of Fortune: Sudanese Soldiers and the River War, 1896–1898, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2011 pp. 33–34 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 1 pp. 238–241 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Harold E. Raugh Jr., British Military Operations in Egypt and the Sudan: A Selected Bibliography, Scarecrow Press, 2008 pp. xxviii–xxix [ISBN missing]

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 pp. 248–259 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 pp. 248–250 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Edward M. Spiers, Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised, Routledge, 2013 pp. 2–3 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 1 pp. 181–184 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 p. 248 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 1 pp. 238–247 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 1 pp. 244–245 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 1 pp. 261–271 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 1 p. 272 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 pp. 312–314 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 pp. 319–321 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 pp. 336–338 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 p. 357 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 pp. 358–360 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 p. 252 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, vol. 2 pp. 66–67 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Harold E. Raugh Jr., British Military Operations in Egypt and the Sudan: A Selected Bibliography, Scarecrow Press, 2008 p. xxix [ISBN missing]

- ^ Robert Collins, A History of Modern Sudan, Cambridge University Press, 2008 pp. 30–31 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Winston Churchill, The River War, Longman 1899 vol. 2 p. 173 [ISBN missing]

- ^ M.W. Daly, Empire on the Nile: The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898–1934, Cambridge University Press, 1986 p. 2 [ISBN missing]

- ^ M.W. Daly, Empire on the Nile: The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898–1934, Cambridge University Press, 1986 p. 3 [ISBN missing]

- ^ M.W. Daly, Empire on the Nile: The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898–1934, Cambridge University Press, 1986 pp. 2–3 [ISBN missing]

- ^ M.W. Daly, Empire on the Nile: The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898–1934, Cambridge University Press, 1986 p. 5 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Max Hastings, The Oxford Book of Military Anecdotes, Oxford University Press, 1986 pp. 308–310 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The Victorian Jihad, 1869–1899, Simon & Schuster, 2007 p. 268 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c M.W. Daly, Empire on the Nile: The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898–1934, Cambridge University Press, 1986 p. 9 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Robert Collins, A History of Modern Sudan, Cambridge University Press, 2008 p. 32 [ISBN missing]