American Brazilians

Descendants of Americans during Confederado feast in Santa Bárbara d'Oeste | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 260,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| São Paulo · Espírito Santo · Rio de Janeiro · Paraná · Pará · Minas Gerais · Bahia · Pernambuco | |

| Languages | |

| Brazilian Portuguese • American English and Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Protestantism and Roman Catholicism and others | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other American and Brazilian people, especially Confederados and other European Americans, Brazilian diaspora in English-speaking countries, other White Latin Americans West and Northern European or Protestant White Brazilians as English, Scottish, Irish, Dutch, Scandinavian, Finnish, Latvian, German (ethnic Germans also among Czech, Russian and Polish immigrants), Austrian, Swiss, French, Luxembourger and Belgian Brazilians |

An American Brazilian (Portuguese: américo-brasileiro, norte-americano-brasileiro, estadunidense-brasileiro) is a Brazilian person who is of full, partial or predominant American descent or a U.S.-born immigrant in Brazil.

The Confederados is a cultural sub-group in the nation of Brazil. They are the descendants of people who emigrated from the Confederate States of America to Brazil with their families after the American Civil War.

At the end of the American Civil War in the 1860s, a migration of Confederates to Brazil began, with the total number of immigrants estimated in the thousands. They settled primarily in Southern and Southeastern Brazil: in Americana, Campinas, São Paulo, Santa Bárbara d'Oeste, Juquiá, New Texas, Xiririca (now Eldorado), Rio de Janeiro and Rio Doce. A few other places also received immigrants: one colony settled in Santarém, Pará – in the north on the Amazon River[2] – and the states of Bahia and Pernambuco also received a significant number of American immigrants.[3]

That was one of the main reasons why emperor Dom Pedro II became the first foreign chief of state and head of government to visit the U.S. capital; he also attended the Centennial Exposition in the largest city in Pennsylvania.[4] More recently, other waves of American nationals became residents in the country.[5]

History

Background and beginning

After the end of the American Civil War, the Confederates found themselves in a very difficult economic situation, having their states completely devastated by the war. Not only the economic issue, as well as the persecution and discrimination that followed against the Confederate population, forced them to seek better living conditions. This flight was the largest population exodus in U.S. history.[6]

They heard about Brazil and the advantages that the emperor gave to anyone who knew how to grow cotton. Before the war, the U.S. South was the world's biggest cotton exporter, exporting to the looms of England and France. The Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II, in his forties, saw the opportunity for Brazil to enter the market and encouraged the arrival of cotton planters from the southern U.S. states to Brazil.[6]

Embittered and wounded, the White American southerners had to draw a little heat from the ashes to keep warm. Many sold their properties, gathered their belongings and came to Brazil, to a land where there were no wars, no trampling and no confiscation of goods.[6]

Emigration companies

Even before the end of the war in 1865, there was already talk of emigrating to Brazil, but very little was known about this country. After the war ended, there was such a revival of the issue that several emigration companies were formed. Representatives were sent to Brazil to check the land, climate and facilities offered by the emperor.[7]

In November 1865, the state of South Carolina formed a colonization society and sent Major Robert Meriwether and Dr. H. A. Shaw, among others, to Brazil to investigate the possibility of establishing a colony. On the way back, they published a report mentioning that two lords had already bought land and settled here.[7]

Many Southerners who accepted the Emperor's offer lost their land during the war, were unwilling to live under a conquering army, or simply did not expect an improvement in the southern economic situation. Furthermore, Brazil would not ban slavery until 1888. The Confederates were the first organized Protestant group to settle in Brazil.[7]

Americana and Santa Bárbara d'Oeste colonies

On December 27, 1865, Colonel and Senator William Hutchinson Norris of Alabama landed in the port of Rio de Janeiro. In 1866, William and his son Robert Norris climbed the Serra do Mar, stopped in São Paulo and speculated on land. They were offered land for free in what is now the neighborhood of Brás, but he did not accept it because it was marsh. They were also offered the land where São Caetano do Sul is today, and they refused for the same reason. They decided to go to Campinas, but at the time, the railroad went only 10 miles beyond São Paulo, and it was no advantage to take it, as Campinas is 45 miles from São Paulo. So the Norris bought an ox cart and headed for Campinas. They took 15 days to reach the city, and there they stayed for a while looking for land, until they cast their sights on the plain that stretched from Campinas to Vila Nova da Constituição, current Piracicaba.[8]

The Norris bought land from the Domingos da Costa Machado sesmaria and established themselves on the banks of Ribeirão Quilombo, at the time belonging to the municipality of Santa Bárbara d'Oeste and where today is the center of the city of Americana. Upon his arrival, Colonel Norris began to give practical courses in agriculture to farmers in the region, interested in cotton cultivation and new agricultural techniques. The plow he brought from the United States caused so much sensation and curiosity that, within a short time, they had a practical agricultural school, with many students who paid him for the privilege of learning and still cultivating their gardens. The Colonel wrote to his family that he had made US$5,000 for that alone. In mid-1867, the rest of his family arrived, accompanied by many relatives.[8]

Numerous farms were founded by North Americans who cultivated and processed cotton. They established an intense trade, notably from 1875 onwards, with the installation of the Santa Barbara Station by the Companhia Paulista de Estrada de Ferro. Due to the constant presence of these immigrants, the village that was formed in the vicinity of the Station became known as "Vila dos Americanos", or "Vila Americana", and gave rise to the current city of Americana.[8]

The installation of the Carioba factory by the North American engineer Clement Willmot and Brazilian associates, located one mile from the train station, also dates from this period. This industry really played a very important role in the foundation and development of Americana. The education of children was one of the priorities for American families who set up schools on the properties and hired teachers from the United States. The teaching methods developed by American teachers proved to be so efficient that they were later adopted by Brazilian official education.[8]

Religious services were celebrated on the properties by pastors who moved between various properties and the various centers of American immigration. In 1895 the first Presbyterian Church was founded in the village of Estação. Due to the prohibition of burying people of other faiths in the cemeteries of cities administered by the Catholic Church, American immigrants began to bury their dead near the farmhouse. This cemetery became known as the Campo Cemetery, currently a tourist attraction in the city of Santa Bárbara d'Oeste. Even today the descendants of American families are buried there. It is in this place that descendants gather periodically for religious cults and parties around the chapel founded in the 19th century.[8]

Amazonas state colony

Jason Williams Stone, an American immigrant of British descent from Dana, Massachusetts, United States, moved to Brazil before the American Civil War, and ended up becoming a tobacco and rubber farmer, soon staying very rich. Jason's plantations, which had more than five thousand hectares, were called Colonia Stone, and were located near the city of Itacoatiara, in Amazonas. Many of his descendants still have the surname "Stone". They are found mainly in the cities of Manaus and Itacoatiara, in Amazonas.[9]

Pará state colony

The city of Santarém, in the state of Pará, received a wave of refugee families from the American Civil War that took place in the South of the United States. The first to land was the Riker family. In the 1970s, David Afton Riker published a book called The Last Confederate in the Amazon, which chronicles the saga of this migration and life in the new homeland. The Confederates and their descendants became notable in the business and political life of the region.[10]

It is not known how many immigrants came to Brazil as war refugees, but unprecedented research in the records of the port of Rio de Janeiro, by Betty Antunes de Oliveira, shows that around 20,000 U.S. citizens entered Brazil between 1865 and 1885.[10]

Descendants and culture

The first generation of Confederates remained an island community. As is typical, in the third generation, most families had already married native Brazilians or immigrants from other origins. Confederate descendants increasingly began to speak the Portuguese language and identify themselves as Brazilians. As the region around the municipalities of Santa Bárbara d'Oeste and Americana became a hub for sugarcane production and society became more mobile, the confederates moved to larger cities in search of jobs urban areas. Currently, only a few families of descendants still live on land owned by their ancestors. The descendants of the confederates are more spread throughout Brazil. They maintain their organization's headquarters at the Campo Cemetery, in Santa Bárbara d'Oeste, where there is also a chapel and a memorial.

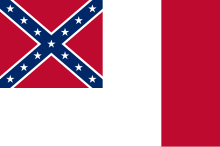

Descendants make a connection to their history through the American Descendant Fellowship, a descendant organization dedicated to preserving immigrant culture. The descendants of the confederates also hold an annual festival in Santa Bárbara d'Oeste called "Festa Confederada", which is dedicated to funding the Campo Cemetery. During the festival, Confederate flags and uniforms are worn, while Southern American food and dances are served and performed. The descendants maintain affection for the Confederate flag, although they identify themselves as fully Brazilian. Many Confederate descendants traveled to the United States at the invitation of Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization of American descendants, to visit civil war battlefields, participate in reenactments, or visit the places where their ancestors lived.[11]

The Confederate flag in Brazil did not acquire the same political symbolism as it has in the United States. After then-Governor Jimmy Carter's visit to the region in 1972, the government of Americana even incorporated the Confederate flag into its coat of arms (although most of the Italian-descendent population removed it a few years later from the city's official symbol, as the descendants of the Confederates now comprise about a tenth of the city's population). During his visit to Brazil, Carter also visited the city of Santa Bárbara d'Oeste and the grave of a great-uncle of his wife, Rosalynn Carter, at Cemitério do Campo. At the time, Carter noted that Confederate descendants sounded and looked exactly like their country's southerners.[11]

Today, the Campo Cemetery (and the chapel and memorial located within it) in Santa Bárbara d'Oeste is a memorial, as most of the region's original Confederate immigrants were buried there. As Protestants, they were prohibited by the Catholic Church from burying their dead in local cemeteries and had to establish their own cemetery. The community of descendants also contributed to the Museum of Immigration, also located in Santa Bárbara d'Oeste, to present the history of U.S. immigration to Brazil.[12]

The American immigrants introduced into their new home many new foods, such as pecans, Georgia peanuts and watermelon; new tools such as the iron plow and kerosene lamps; innovations such as modern dentistry, modern agriculture, and the first blood transfusion; and the first non-Catholic churches (Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist).[13]

Immigration in numbers

- American immigration to Brazil by State up to January (1867)[14]

| State | Immigrants |

|---|---|

| São Paulo | 800 |

| Espírito Santo | 400 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 200 |

| Paraná | 200 |

| Pará | 200 |

| Minas Gerais | 100 |

| Bahia | 85 |

| Pernambuco | 85 |

| Total | 2,070 |

The Confederate emigres were some 20,000 Southerners, from 12 southern states (i.e. Arkansas, Alabama and Mississippi) who preferred the Brazilian wilderness to life under Yankee rule after the Civil War.[15]

Descendants of the immigrants

- Number of American descendants by state

| State | Descendants |

|---|---|

| São Paulo | 100,490 |

| Espírito Santo | 50,258 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 25,220 |

| Paraná | 25,000 |

| Pará | 24,800 |

| Minas Gerais | 12,610 |

| Bahia | 10,686 |

| Pernambuco | 10,000 |

| Total | 260,000 |

Education

Today, Brazil is home to many American schools.[16]

-Chapel International School

-Pan American Christian Academy

- St. Francis College

-American School of Campinas

-American School of Rio de Janeiro

-ICS – International Christian School – Rio

-Our Lady of Mercy School

-Brasília International School

-American School of Belo Horizonte

-Pan American School of Porto Alegre

-International School of Curitiba

- Pará:

-International School of Amazonas

Notable people

- Luís Inácio Adams

- Zuzu Angel

- Orville Adalbert Derby, geologist

- Eduardo Dougherty

- Bob Falkenburg

- Charles Frederick Hartt

- David Neeleman

- Llewellyn Ivor Price

- Júlio Ribeiro

- Fabiana Semprebom, model

- Tim Soares (born 1997), basketball player for Ironi Ness Ziona of the Israeli Basketball Premier League

- Dorothy Stang

- Larry Taylor, basketball player

- Dionne Warwick

- Ellen Gracie Northfleet, judge

- Elsie Lessa

- Ivan Lessa

- José Lewgoy, actor

- Rita Lee

- Warwick Kerr

- Kátia Lund

- Lewis Joel Greene

- William Hutchinson Norris

- Guy Ecker, actor

- Arminio Fraga Neto

See also

References

- ^ US Embassy in Brazil Archived July 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine US Embassy in Brazil. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Confederate Colonies of Brazil Archived May 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "North American immigrants in Brazil: myth and reality, the case of Santa Barbara" (PDF). Instituto de Economia / UNICAMP. July 29, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 4, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ "Visits to the U.S. by Foreign Heads of State and Government—1874–1939". 2001-2009.state.gov. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Embaixador dos Estados Unidos Todd C. Chapman chega ao Brasil". Embaixada e Consulados dos EUA no Brasil (in European Portuguese). March 29, 2020. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "This story is no longer available – Washington Times". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Confederates in Brazil – Article". mason.gmu.edu. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Folha de S.Paulo – SP abriga sulista que o vento levou – 16/03/98". Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ "Jason W. Stone b. 19 Feb 1830 Dana, Worcester, Massachusetts d. 1913 Itacoatiara, Amazonas, Brazil: Whipple Database". Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ a b O último confederado na Amazônia (Book, 1983). [WorldCat.org]. January 4, 2019. OCLC 12972743. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "G1 > Edição São Paulo – NOTÍCIAS – Descendentes de confederados celebram em SP o fim da Guerra Civil dos EUA". Archived from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "Secretaria Municipal de Cultura e Turismo de Santa Bárbara d'Oeste". Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Orrizio, Riccardo. Lost White Tribes: The End of Privilege and the Last Colonials in Sri Lanka, Jamaica, Brazil, Haiti, Namibia, and Guadeloupe. Simon and Schuster, 2001, pages 110–111.

- ^ "Brasil: migrações internacionais e identidade". Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ^ "Total U.S. Immigration". Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- ^ "American Schools in Brazil". Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

Further reading

- Harter, Eugene C. (2000). The Lost Colony of the Confederacy. Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 1585441023.