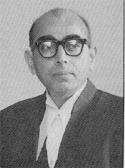

A. N. Ray

Ajit Ray | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th Chief Justice of India | |

| In office 26 April 1973 – 28 January 1977 | |

| Appointed by | V. V. Giri |

| Preceded by | Sarv Mittra Sikri |

| Succeeded by | Mirza Hameedullah Beg |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 January 1912 |

| Died | 25 December 2009 (aged 97) Kolkata, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

Ajit Nath Ray (29 January 1912 – 25 December 2009) was the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India from 25 April 1973 till his retirement on 28 January 1977.

Ray was the lone dissenter among the eleven Supreme Court judges that examined the constitutionality of the Bank Nationalization Act, in 1969. He had come to his appointment to the Court via Presidency College, Calcutta, Oriel College, Oxford, Gray's Inn, and the Calcutta High Court.[1] His son Justice Ajoy Nath Ray was the Chief Justice of the Allahabad High Court.[2]

Controversial appointment

In August 1969, he was appointed as Judge of the Supreme Court of India, and became Chief Justice of India in April 1973.

His appointment as CJI came on the heels of a dissenting opinion in the Keshavanand Bharti case which gave rise to the Basic structure doctrine of the Indian Constitution.

This appointment superseded three senior judges of the Supreme Court, Jaishanker Manilal Shelat, AN Grover and K. S. Hegde, and was viewed as an attack on the independence of the Judiciary. This was unprecedented in Indian legal history, and has been called the "blackest day in Indian democracy".[3] It was marked by widespread protests by bar associations and legal groups across India. The protests continued for many months and on 3 May 1976 all legal groups in India observed a "Bar solidarity day" and stopped from work.[3]

Justice Mohammad Hidayatullah (who was CJI earlier) remarked that "this was an attempt of not creating 'forward looking judges' but the 'judges looking forward' to the plumes of the office of Chief Justice".[3] The process continued with the controversial appointment of Justice Beg superseding Hans Raj Khanna in 1977.

After becoming Chief Justice, A.N. Ray more than shared the government's economic viewpoint – he developed an adulatory attitude towards Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. He made himself amenable to her influence by telephoning her frequently, and also ask her personal secretary's advise on simple matters, conveying the impression that Prime Minister's views might be heard concerning an ongoing court-case.[4]

Ultimately, the powers of the Judiciary over judicial appointments was re-established under the Morarji Desai government with Shanti Bhushan as law minister through various Constitutional amendments.

Additional District Magistrate of Jabalpur v. Shiv Kant Shukla (also known as the Habeas corpus case) is a major decision during his tenure as Chief Justice, where the Supreme Court infamously espoused the view that no court could enforce the right to life during the imposition of Emergency. In other words, even if life is taken illegally during an Emergency, the court would stay helpless. After the Emergency was over, the 44th Amendment Act of 1978 protected the fundamental rights under Article 20 and Article 21 from being violated during an Emergency. In 1978-decision in Maneka v. Union of India case, 'due process of law' concept was brought in where deprivation of a person's liberty can't be done by a law which is arbitrary, unfair or unreasonable. The IR Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu case was a landmark 2007 Supreme Court of India ruling that established the importance of judicial review and the basic structure doctrine of the Constitution. Finally, in 2017-decision of KS Puttaswamy v. Union of India case, the Supreme Court overruled the infamous Habeas Corpus case's majority decision.[5]

References

- ^ Austin, Granville (1999). Working a Democratic Constitution – A History of the Indian Experience. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 216–217. ISBN 019565610-5.

- ^ Socialist India. Indian National Congress. All India Congress Committee. 1974. p. 2.

- ^ a b c "Supreme Court Bar Association". Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Austin, Granville (1999). Working a Democratic Constitution – A History of the Indian Experience. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 290. ISBN 019565610-5.

- ^ Dhingra, Anjali (24 September 2024). "A.D.M. Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla (1976)". iPleaders. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

External links