Ageing of Europe

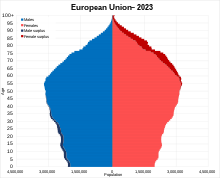

The ageing of Europe, also known as the greying of Europe, is a demographic phenomenon in Europe characterised by a decrease in fertility, a decrease in mortality rate, and a higher life expectancy among European populations.[1] Low birth rates and higher life expectancy contribute to the transformation of Europe's population pyramid shape. The most significant change is the transition towards a much older population structure, resulting in a decrease in the proportion of the working age while the number of the retired population increases. The total number of the older population is projected to increase greatly within the coming decades, with rising proportions of the post-war baby-boom generations reaching retirement. This will cause a high burden on the working age population as they provide for the increasing number of the older population.[2][3]

Throughout history many states have worked to keep high birth rates in order to have moderate taxes, more economic activity and more troops for their military.[4]

Population ageing is observed in most European countries today.

Overall trends

Giuseppe Carone and Declan Costello of the International Monetary Fund projected in September 2006 that the ratio of retirees to workers in Europe will double to 0.54 by 2050 (from four workers per retiree to two workers per retiree).[1][5] William H. Frey, an analyst for the Brookings Institution think tank, predicts the median age in Europe will increase from 37.7 years old in 2003 to 52.3 years old by 2050 while the median age of Americans will rise to only 45.4 years old.[citation needed]

Máire Geoghegan-Quinn, the former European Commissioner for Research, Innovation and Science, stated in 2014 that by 2020 a quarter of the population of Europe will be 60 years or older. This shift in demographics will drastically change the economic, labor market, health care, and social security of Europe.[6]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates 39% of Europeans between the ages of 55 to 65 work.[7]

Austria's Social Affairs Minister said in 2006 that, by 2010, the 55- to 64-year-old age bracket in the European Union would be larger than the 15- to 24-year-old bracket. The Economic Policy Committee and the European Commission issued a report in 2006 estimating the working age population in the EU will decrease by 48 million, a 16% reduction, between 2010 and 2050, while the elderly population will increase by 58 million, a gain of 77%.[citation needed]

In 2002, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates the European Union will experience a 14% decrease in its workforce and a 7% decrease in its consumer populations by 2030.[8]

The feminisation of old age is reflected by an increasing number of females age 65 and older. The longer life span is prevalent amongst women across the world.[9] In Europe the life expectancy for women is 81 years old, while men's life expectancy is only 74 years old, which gives 7 years' difference.[10] Life expectancy at age 60 is four years longer for women in comparison to men. Projections show additional 24 years for females and 20 years for males in Europe.[10]

Causes

Population ageing in Europe is caused primarily by three factors: declining fertility rates, increased life expectancy, and migration.[10] The causes of population ageing vary among countries.

Fertility

The high number of people aged 60 and older in Europe is the result of high fertility rates which occurred 1950–1960.[10] The period after the end of World War II was characterised by good social and economic status of the population in the child-bearing age and resulted in a "baby boom".[11]

Current low fertility levels also contribute to the ageing of Europe.[10] As the fertility levels drop, the age structure of the population changes, and the number of the younger groups decrease in relation to the older age groups.[10] Europe's fertility rates have been less than the 2.1 children per woman (standard) replacement level and are projected to remain below the replacement level in the future.[12]

Mortality

People are living longer with projections of average life expectancy reaching 84.6 years for men and 89.1 for women by 2060, an increase of 7.9 years of life for men and 6.6 years of life for women compared to 2010.[12] The longer life span results in the changing age structure in the population by increasing the numbers of people in the older age group.[10] The average life expectancy of the older population will depend on the progress in medicine to prevent the diseases which are the leading causes of death.[10] Among the top three causes of death are ischemic artery disease, stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[10]

Migration

People immigrating and emigrating from the country will cause fluctuations, in particular, in the size of the working age group of the population.[9] If there are high numbers of young immigrants coming to the country it will result in a decrease of the proportion of the ageing population.[10] In the following countries immigration is projected to slow the population ageing: Luxembourg, Switzerland, Norway, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Belgium, Denmark, Austria and United Kingdom.[10] Emigration would cause the opposite effect on population ageing by having people in the working age leaving the country, and accelerating the ageing of the population as a result.[10] Increase of the ageing population caused by emigration is projected to occur in Latvia.[10]

Effects

Populations in Europe react in different ways to demographic changes, depending on what is happening in their countries. Both ageing, emigration and immigration can cause anxiety in populations of individual countries.[13] Demographic studies and resultant reports conducted by the European Commission[14] point to the declining birth rate of the population of the native European peoples, which would need to be reversed from its present level of about 1.4 in order to preclude a population decline of the native European peoples by nearly half in each generation, back to a replacement level of 2.1. Some have claimed that in order to compensate, it is necessary to allow migrants to settle in Europe in order to prevent labour shortages. It has been argued that such immigration leads to ethnic conflicts, such as the 2005 civil unrest in France.[15][16][17]

The ageing population in Europe had multiple consequences on the changes in the political and economic narratives and discourses.

As the proportion of individuals in the workforce declines relative to those relying on welfare systems (i.e., as the dependency ratio rises), significant financial challenges emerge [18] . Policymakers often frame the ageing population as an economic threat. For instance, the World Bank’s 1994 report, Averting the Old Age Crisis, critically examined the role of pension systems in fostering economic growth. Similarly, the European Commission, starting in 1997, began recommending reforms to pension schemes, and by 2001, the European Council officially recognized ageing as a critical policy issue for the European Union [19]. Numerous articles and reports underscore a tone of concern regarding the growing ageing population and its associated costs, particularly rising expenditures on pensions, healthcare, and social care [20]. This narrative is echoed in academic literature. For instance, Gruber and Wise [21] observed that between 1980 and 1995, the proportion of individuals aged 65 and above in OECD countries rose by 20%, while expenditure on this demographic increased by 25%.

However, Timonen [22] argues that ageing matters less than what is expressed, highlighting several reasons why its impact may be less severe than commonly portrayed. One key argument is that older individuals contribute to the economy and society in various meaningful ways. For instance, many older adults continue to engage in paid work, and post-retirement employment is an increasingly prevalent trend across Europe, especially so in the north part of Europe. Additionally, older individuals play a crucial role in family dynamics through grandparenting, which enables their children or other relatives to participate in the workforce without the added responsibility of childcare. Beyond this, they often provide care for spouses or other adult family members and are active in voluntary work. Furthermore, older adults frequently participate in the intergenerational redistribution of material resources, offering financial support to younger family members.[23][22]

The political preferences of ageing population

It is first important to highlight that the older population is not a homogeneous group with uniform interests or characteristics before exploring their general political preferences. While they often share distinct traits compared to younger generations, significant diversity exists within this age group. Variations in health, income, education, cultural backgrounds, and life experiences mean that older individuals often have differing needs, preferences, and priorities. [22]

At the same time, as the share of those working goes down, the demand for pensions, health and social care goes up because the elderly represent a distinct electoral influence. They become a voting block that want to defend their interests and present particular characteristics such as having a particularly high electoral turnout [24]. Indeed, pre-baby boomer generations have a higher turnout than the generations post-baby boom for national elections as well as for the European Parliament elections [25]. Older people are also more likely to change their party choice for more conservative ones. They tend to vote with the right parties more than the younger cohort. The reasons behind this appears to be more contested by academics. [26] They have as well certain policy preferences like on the one hand, low support for education spendings [27] and on the other hand, high support for health spendings [28]. Concerning the support for childcare, it depends whether there are often contact with grandchildren, bringing up the solidarity [29]. But overall, studies are often demonstrating that there are less support for welfare expenditure for the younger in the elderly’s eyes. [24]

As for the question of energy efficiency and environmental policies, the elderly’s position on the question is that they are less likely to support such policies and an increasing welfare state generosity for them doesn’t help their position on the matter, and even make their position more adverse. One reason for such attitude is that their immediate future (economically and health-related) has a priority on the sustainability of the environment. Additionally, they might be worried that there could be a reallocation of resources for the realisation of environmental policies in the detriment of pension benefits. [30]

However, the preferences of older populations regarding pension reforms have yielded mixed findings in academic research [24]. For instance, Fernández and Jaime-Castillo [31] found that older individuals tend to oppose pension reforms but support changes that extend working years, reflecting a willingness to ensure the sustainability of pension systems. In contrast, Lynch and Myrskylä [32], using data from 11 European countries between 1992 and 2001, found no evidence to support this claim. At the country level, older populations exhibit unique perspectives shaped by local conditions. In Finland, older individuals approach pension issues with a critical perspective, while they advocate for increased pension spending [33]. Similarly, in Germany and France, older populations significantly ask for higher pension expenditures [34].

Still, in ageing countries, there is a priority on pensions and healthcare in policies over education and childcare. The preferences of the older population in Europe have an effect on the public spending due the high number of individuals that they represent compared to the younger voters and political parties often react according to the preferences of their potential electorates. They are often called grey power. [24] They are also more likely to be members of political parties themselves and the older population that ages in between 60-69 years old are more often part of union groups than other ages (apart from the cohort in between 50-59 years old). Because they hold such big influence, some academics have started to talk about gerontocracy, in particular in Germany. An illustrative example of the influence of the elderly on economic policy can be seen in their impact on inflation. Unlike younger demographics, the elderly have little reason to prioritize employment prospects, as they are typically retired and no longer participating in the labour market. Additionally, many older individuals have already repaid their debts, reducing their personal exposure to the adverse effects of higher inflation, such as eroded purchasing power on fixed incomes or increased borrowing costs. As a result, inflation is often not perceived as a particularly attractive or pressing economic objective for this demographic. This perspective is reflected in macroeconomic trends: countries with larger ageing populations tend to exhibit lower inflation rates compared to those with younger populations [35].

According to Vlandas [36], that demonstrates why ageing countries end up choosing to support less efficient economic policies. As such, elderly voters punish the government through their votes when the inflation is high, but not when the unemployment level is high. Another more meaningful concern for them is the house pricing. To add on to that, when governments lead to poor economic performance due to their strategies, they are not faced with penalties from the older population. Especially since, as the ageing population benefits from the pension security, they are not at risk like the workers who might face job insecurity for instance. Because of the results of low inflation and low growth in ageing countries, this leads for the government to opt for more conservative monetary policies with a delegation to independent central bank, which prioritize only inflation control. Furthermore, as the priority of financing education, innovation and social and human capital in general is shifted towards the preferences of older voters, this leads to a lack of investment in infrastructure that could support long-term economic growth. As a consequence, it would make it difficult for governments and politicians to address the issues behind a poor economic performance. [36]

Influence on political reforms

The demographic situation in Europe, characterized by an ageing population and declining birth rates, has prompted national governments to implement various policy measures in response. These policies are shaped by two main influences. On the one hand, there is the significant political and social weight of the older population, whose preferences can potentially drive policy decisions [24]. On the other hand, there is the perceived economic threat posed to the welfare system, as rising costs for pensions, healthcare, and social care strain public finances [37].

Timonen [22] and Coole [38] identify several potential policy solutions to address these challenges. These include promoting pronatalism, with the aim of increasing birth rates through family-friendly policies; implementing public health initiatives to improve overall population health and reduce long-term healthcare costs for example; and encouraging immigration to supplement the labour force and offset demographic decline. Additionally, reforming social policies is often suggested, such as raising the retirement age to extend working years, reducing entitlements, rationing treatments to prioritize resources, and enhancing productivity and labour market participation to strengthen economic sustainability.

Labour market participation in 55–64-year-old cohorts

One approach to increasing labour market participation is by improving employment rates among individuals nearing retirement age. Across Europe, employment rates for people aged 55 to 64 remain low, with notable differences between men and women in this age group. And the European Commission made a focus on increasing older worker employment rates in 2010 [39]. However, this objective of active ageing faces different results depending on the countries. In 2008, Hartlapp and Schmid [40] estimate that when we consider a goal of an employment rate of 50% for the older workers (55-64 years old), Ireland, Scandinavian countries and others had reached that target if we only considered men. Other countries (France, Belgium, Austria, Italy, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia) had not reached it yet. However, when it came to women employment in that age set, the labour force participation was even lower. The reasons behind this difference are multiple. One of the reasons is demonstrated by the importance of care work for women that is still unequal compared to men [39].

To encourage older worker’s participation to labour market, policies can enable more flexible forms of employment, as arrangements to the working time could allow older workers to have better work-life balance. Other measures include strategies to combat age discrimination, promote education and training (to develop ICT skills for example), policies to support caregiving outside of the family and health policies [40] [39]. An example of policy would be countries (such as Ireland, Belgium, Germany Lithuania and Poland), that subsidizes the firms that provide training to their older workers [41].

Pension Reforms

Over the past 30 years, the pension system of the European Union has faced a number of innovations and recalculations to create a fair and sufficient pension for all its recipients. Pension reforms were focused on two main aspects of senior and pre-senior lives: revaluation of pension sum and change of normal pensionable age to guarantee equity and minimize fiscal outlays [42] . The most popular methods of pension’s recalculation used within the EU include “creeping entitlement” (a tool that allows governments to index pensions less frequently, thus reducing government budgetary costs without attracting criticism from voters) [43], as well as the concept of calculating a pension based on a comprehensive analysis of an individual’s entire work history, rather than only their highest earning years prior to retirement.[42]

In Europe, the population is growing older, but the number of young people is not increasing at the same pace, resulting in a shift in the demographic balance. Migration is positively impacting the demographics of the European Union , contributing to the growth of young professionals. However, it is inevitable that they will eventually age as well. [42] To solve this issue, some Member States have moved to raise the state pension age (for example, Ireland to 68 years by 2028, and Germany to 67 years by 2031). However, some contend that this would be unfair. [44]

Firstly, there are professions that are hazardous to health. For instance, individuals who work in difficult conditions, face risks, and experience health deterioration, may receive an increase in their retirement age. In other words, they do not live to retire, and thus their shares are given to others. Consequently, some countries, such as Austria, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and Finland, have established lower eligibility ages (without penalties) for workers with long careers or for certain professions [45]. Secondly, the emergence of highly skilled labor in the past 50-60 years has altered life expectancy, resulting in a disparity between workers not only in wages but also in the number of years lived (higher pensions and longer lifespans). [42]

Immigration

Another approach to increasing labour market participation could be increased immigration. The European Commission describes in 2005 immigration as a way to reinforce population and manpower which would allow for prosperity. However, details remain blurry as to numbers because, while there may be economic benefits, immigration comes also with its set of social challenges. Another argument against it, is the fact that the immigrants with time will also grow old and need pensions. Especially because the idea that those coming from high-fertility cultures would come and have numerous newborns is unfounded. Secularisation theory shows that the immigrants tend to adopt the low-fertility habits of their new country. In most European countries, this means aligning with the prevailing trend of low fertility rates. Therefore, it would lead to only limited enlargement of the working population. According to this theory then, while immigration may temporarily boost the working-age population, its long-term effect on demographic structures is limited. [46] [22]

Pronatalism

This covers policies that demand quality childcare, kindergartens, schooling, medical care, etc. that would increase the birth rate and therefore would increase the working population leading to potential economic growth [46] [22] . Fertility decline can, under certain conditions, be mitigated through the implementation of appropriate policies [22] . One example highlighted by the RAND study involves promoting childbearing among couples. Evidence from France demonstrates the potential effectiveness of pronatalist policies. Between 1993 and 2002, these measures significantly increased the country's fertility rate, enabling France to achieve the second-highest fertility rate in Europe, surpassed only by Ireland [22].

Overall, increasing population is sometimes argued to be undesirable. First, it is often seen as a necessity after rapid growth in developed country. Additionally, an increasing density of the population affects negatively quality of life and affects negatively as well the environment. [47] Another argument that is pushed forward is that the high level of unemployment among the working population, and particularly for the younger ones is alarming [46]. Another challenge is the one that poses the policymakers. And one of the reasons behind this is the lack of immediate results of the pronatalist policies, as the benefits of such policies may not become clear at the end of their term in office [22] .

Intenational Organizations Actions

UN

Some frameworks have contributed greatly to the policies linked to aging in Europe, such as the Vienna International Plan of Action on Ageing (1982) and the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (MIPAA) (2002), by United Nations [48]. These frameworks promote sustainable development in aging societies, health and well-being in late life and environments conducive to an older person's community engagement [49]. There is also a dedicated database on the UNECE website that contains all available information and research related to ageing policies called “Ageing Policies Database” [50].

WHO

The World Health Organization has created a comprehensive policy framework for an ageing society, focusing on health, participation, and security for older individuals. Its projects emphasize the need to prevent chronic diseases and disabilities through gender-specific health targets, improved access to effective treatments, and the creation of age-friendly environments. The framework advocates for policies that support social inclusion, mental health, and access to clean environments, while addressing the economic factors affecting health outcomes for older populations. In addition, it promotes lifelong learning and participation in economic activities, ensuring older people have access to education and opportunities that align with their preferences and capacities [51]. The aging of the population is changing the proportion of workers and dependents. Simultaneously, the standard of medical care and living are improving. [42]

Countries

Belgium

The International Monetary Fund's (IMF) High Council of Finance's (HCF) Study Committee on Ageing (SCA) predicted in 2007 that Belgium's population will increase by 5% by 2050 due to immigration, a higher fertility rate, and longer life expectancy. However, the IMF's study indicates Belgium's elderly population will increase by over 25% to over 63% of the country's overall population.[citation needed]

The Belgian government spent 9.1% of its GDP on pensions and 7.1% on health care expenses in 2005. By 2050 total social spending is expected to increase by 5.8%, assuming there is no change in the age of retirement. Most of this higher social spending comes from pension and health care, rising by 3.9% to 13.0% of GDP and 3.7% to 10.8% of GDP, respectively.[citation needed]

The decline in the workforce will partly compensate by lowering unemployment which will in turn lower the cost of childcare.[52] The IMF also predicts that by 2050 the percentage of Belgian population over the age of 65 will increase from 16% to 25%.[53]

In 2017 24.6% of the population of Belgium was over 60 years old, and it is projected to increase to 32.4% by the year 2050.[10] The life expectancy at birth in 2010–2015 is projected to be 83 years for females and 78 years for males.[10]

Finland

Finland has one of the oldest populations of Europe. The so-called baby boomer generation born between 1945 and 1949 has already retired, and the share of over-65-year-olds of the population will increase from 20 percent in late 2010s to 26 percent by 2030 and to 29 percent by 2060.[54] In comparison to its Nordic neighbours, a low share of Finnish people older than 61 years are still working. The government has aimed to increase their share in work life following the OECD recommendations.[55] The increasing share of old people is predicted to burden the Finnish social welfare and pension system heavily in the following decades, increasing pressure to raise taxes. The collapse in fertility rates from 1.81 to just 1.34 in Finland during 2010s has made the future forecasts even more severe, as the share of working aged population will decrease by hundreds of thousands by 2050s.[56] Also regional distribution of older people is uneven: the peripheric Finnish provinces will have a much higher share of elderly people than growing regions such as Uusimaa and Pirkanmaa.

According to 2019 estimate, the population of Finland will start decreasing by 2031, and in 2050 it will be some 100.000 lower than in 2019, given that migration will remain stable.[57]

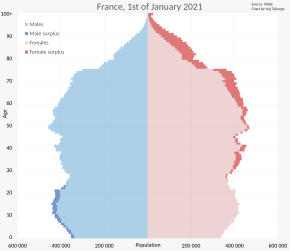

France

France overtook Ireland as the European Union member state with the highest birth rate in 2007.[58] Projected birth rates indicate that France will have the largest population in the EU by 2050, with 75 million citizens, overtaking Germany,[59] but only the second largest in Europe, with the UK having a larger estimated population. In 2011, France was the only European Union member with a fertility rate at replacement level, with an average rate of 2.08 children per woman while Ireland's fertility rate declined to 2.01 children per woman, slightly below replacement level.[60] The reason for an increase in children is due to the government family benefits that are provided to these families.[citation needed] They receive an allowance based on income and how many children they have in the household.[61]

The total fertility rate (TFR) fell to 1.99 children per woman in 2013 from 2.01 in 2012 and 2.03 in 2010. A rate of 2.1 children per woman is considered necessary to keep the population growing excluding migration.[62]

For the year 2017 the percentage of population aged 60 or older was 25.7%, and projected to increase to 32.2% by 2050.[10] The life expectancy at birth in 2010–2015 is projected to be 85 years for females and 79 years for males.[10]

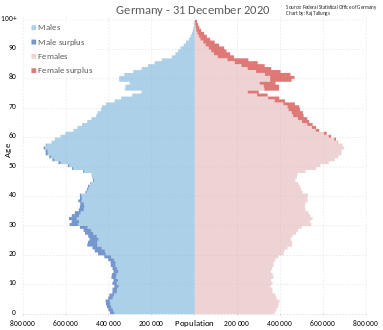

Germany

With over 83 million inhabitants in September 2019,[63] Germany is the most populous country in the European Union. However, its fertility rate of 1.596 children per woman in 2020 is very low,[64] and the federal statistics office estimates the population will shrink to between 65 and 70 million by 2060 (65 million assuming a net migration of +100,000 per year; 70 million assuming a net migration of +200,000 per year).[65] With death rates continuously exceeding low-level birth rates, Germany is one of a few countries for which the demographic transition model would require a fifth stage in order to capture its demographic development.[66] In Germany, the population in some regions, especially the former Communist East Germany, is undergoing a current decline and depopulation. The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation came up with comprehensive plans to tear down numerous buildings and replace them with parks in various cities[16] and the government of Germany developed a plan to reduce at great expense the width of sewer pipes in various cities. The southern states, however, have net gain in population and Germany as the economic powerhouse of the EU is attracting immigrants overall.

In 2017 28.0% of the population of Germany was over 60 years old, and it is projected to increase to 37.6% by the year 2050.[10] The life expectancy at birth in 2010–2015 is projected to be 83 years for females and 78 years for males.[10]

- Population of German territories 1800–2000 and immigrant population 1975–2000

- Population pyramid of Germany at the end of 2020

Italy

Under current fertility rates, Italy will need to raise its retirement age to 77 or admit 2.2 million immigrants annually to maintain its worker to retiree ratio.[67] About 25% of Italian women do not have children while another 25% only have one child.

The region of Liguria in northwestern Italy now has the highest ratio of elderly to youth in the world. Ten percent of Liguria's schools closed in the first decade of the 21st century. The city of Genoa, one of Italy's largest and the capital of Liguria, is declining faster than most European cities with a death rate of 13.7 deaths per 1,000 people, almost twice the birth rate, 7.7 births per 1,000 people, as of 2005.[citation needed]

The Italian government has tried to limit and reverse the trend by offering financial incentives to couples who have children, and by increasing immigration. While fertility has remained stagnant, immigration has minimised the drop in the workforce.[68]

In 2017 29.4% of the population of Italy was over 60 years old, and it is projected to increase to 40.3% by the year 2050.[10] The life expectancy at birth in 2010–2015 is projected to be 85 years for females and 80 years for males.[10]

Poland

The economic effects of demographic shifts will be less concerning in Poland than in its neighboring countries even though it is expected to lose 15 percent of its population by mid-century.[12] It is projected that by 2050 population of Poland will decrease to 32 million due to the emigration and low birth rates. The fertility rates have dropped from 3.7 children per woman in 1950 to 1.32 children per woman in 2014. This drastic drop would affect the economy of Poland.[69]

In an effort to reverse declining birth rates, the Polish government in 2016 introduced a policy of paying 500 zlotys (about US$128) per month to families for every child below the age of 18 after the first child.[70] The policy has since then been extended to the first child as well.

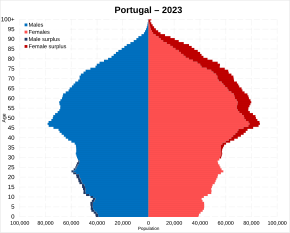

Portugal

Portugal's population census of 1994 found that 13.1% of the population was above the age of 65. Average life expectancy for Portuguese increased by eight years between the 1980s and the first decade of the 21st century.[71] In 2017 the population of the people aged 60 and more was 27.9%, with an estimate to increase in 2050 to 41.7%.[10] The life expectancy at birth in 2010–2015 is projected to be 83 years for females and 77 years for males.[10]

In the 1960s life expectancy for men ranked comparatively low in relation to other Western European nations, with 61.2 years for men and 67.5 years for women. As of 2006, the average for both sexes was at 77.7 years. In 1999 demographers predicted the percentage of elderly Portuguese would increase to 16.2% and 17.6% in 2010.[72]

Recent studies in the newspaper Público showed that the population may shrink to 7.5 million (−29% of the current population, −0.7% of average populational growth per year) in 2050, if the fertility rate continues at 1.45 children per woman; taking into account the almost stationary emigration due to the economic crisis.[citation needed] In 2011, Portugal's fertility rate reached 1.51 children per woman, stemming the decline in the nation's fertility rate, although it is still below replacement level.[64]

Spain

In 1970, Spain's TFR of 2.9 children per woman ranked second in Western Europe after Ireland’s's rate of 3.9. By 1993 Spanish fertility declined to 1.26 children per woman, the second-lowest after Italy.[citation needed]

In recent years, Spain's fertility rate has been more constant ranging from 1.23 (in 2000 and 2020) to 1.45 (in 2009).[64]

In 1999, Rocío Fernández-Ballesteros, Juan Díez-Nicolás, and Antonio Ruiz-Torres of Autónoma University in Madrid published a study on Spain's demography, predicting life expectancy of 77.7 for males and 83.8 for females by 2020.[73] Arup Banerji and economist Mukesh Chawla of the World Bank predicted in July 2007 that half of Spain's population will be older than 55 by 2050, giving Spain the highest median age of any nation in the world.[citation needed]

In 2017 25.3% of the population of Spain was over 60 years old, and it is projected to increase to 41.9% by the year 2050.[10] The life expectancy at birth in 2010–2015 is projected to be 85 years for females and 79 years for males.[10]

United Kingdom

The UK had a fertility rate of 1.68 in 2018 according to the Office for National Statistics.[74] In 2019, England had a TFR of 1.66, and Wales had a TFR of just 1.54.[75] Scotland's TFR was 1.37 in 2019.[76] In 2017, N.Ireland had a TFR of 1.87.[75] By 2050, it is projected that one in four people in the UK will be aged 65 years and over – an increase from approximately one in five in 2018.[77] According to the ONS' principal projection for the UK from 2019 data, the population is due to rise to over 73.6 million by 2050.[78]

In mid-2019, there were 12.4 million people aged 65 years and over (18.5%) and 2.5% were aged 85 years and over.[79] The proportion aged over 65 is forecast to rise to a quarter by 2050.[80][10] Life expectancy at birth in the UK in 2020, using the 2017 to 2019 tables to make projections, was 79.4 years for males and 83.1 years for females.[81]

Other regions

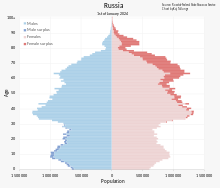

Russia

The current[when?] Russian total fertility rate is 1.7 children per woman.[82] While this represents an increase over previous rates, it remains sub-replacement fertility, below the replacement rate of 2.10–2.14.

The population of the Russian Federation declined from its peak of 148,689,000 in 1991, to about 143 million people in 2013, a 4% decline. The World Bank predicted in 2005 that the population was set to decrease to 111 million by 2050, a 22% decline, if trends did not improve.[83] The United Nations similarly warned that the population could decline by one third by mid-century.[84]

In 2006 a national programme was developed with a goal to reverse the decline by 2026. A study published shortly after in 2007 showed that the rate of population decrease had slowed: According to the study, deaths exceeded births by 1.3 times, down from 1.5 times in the previous year, thus, if the net decrease in January–August 2006 was 408,200 people, in the same period during 2007 it was 196,600. The decline continued to slow in 2008 with only half the population loss compared to 2007. The reversal continued at the same pace in 2009 as death rates continued to fall, birth rates continued to rise and net migration stayed steady at about 250,000; in 2009 Russia saw population growth for the first time in 15 years.[85][86]

| Year | Population growth[87][88] |

|---|---|

| 2000 | −586,000 |

| 2001 | −655,000 |

| 2002 | −685,000 |

| 2003 | −796,000 |

| 2004 | −694,000 |

| 2005 | −720,000 |

| 2006 | −554,000 |

| 2007 | −212,100 |

| 2008 | −121,400 |

| 2009 | +23,300 |

The improving economy has had a positive impact on the country's low birth-rate, as it rose from its lowest point of 8.27 births per 1000 people in 1999 to 11.28 per 1,000 in 2007. Russian Ministry of Economic Development hopes that by 2020 the population will stabilise at 138–139 million, and that by 2025 it will begin to increase again to its present-day status of 142–145, also raising the life expectancy to 75 years.[89]

The two leading causes of death in Russia are heart disease and stroke, accounting for about 52% of all deaths.[90] While cardiovascular disease-related deaths decreased in Japan, North America, and Western Europe between 1965 and 2001, in Russia CVD deaths increased by 25% for women and 65% for men.

The percentage of infertile, married couples rose to 13% in the first decade of the 21st century, partially due to poorly performed abortions. According to expert Murray Feshbach 10–20% of women who have abortions in Russia are made infertile, though according to the 2002 census, only about 6–7% of women have not had children by the end of their reproductive years.[91][92]

Mothers who give birth on 12 June, Russia's national day, are rewarded with money and expensive consumer items. In the first round of the competition 311 women participated and 46 babies were born on the following 12 June. Over 500 women participated in the second round in 2006 and 78 gave birth. The province's birth rate rose 4.5% between 2006 and 2007.[93]

Large-scale immigration is suggested as a solution to declining workforces in western nations, but according to the BBC, would be unacceptable to most Russians. Organisations like the World Health Organization and the UN have called on the Russian government to take the problem more seriously, stressing that a number of simple measures such as raising the price of alcohol or forcing people to wear seat belts might make a lasting difference.[84]

Then-President Vladimir Putin said in a state of the nation address that "no sort of immigration will solve Russia's demographic problem". Yevgeny Krasinyev, head of migration studies at the state-run Institute of Social and Economic Population Studies in Moscow, said Russia should only accept immigrants from the Commonwealth of Independent States, a view echoed by Alexander Belyakov, the head of the Duma's Resources Committee.

Migration in Russia grew by 50.2% in 2007, and an additional 2.7% in 2008, helping stem the population decline. Migrants to Russia primarily come from CIS states and are Russians or Russian speakers.[94] Thousands of migrant workers from Ukraine, Moldova, and the rest of the CIS have also entered Russia illegally, working but avoiding taxes.[95] There are an estimated 10 million illegal immigrants from the ex-Soviet states in Russia.[96]

Central Europe and the former Soviet Union

The World Bank issued a report on 20 June 2007, "From Red To Grey: 'The Third Transition' of Aging Populations in central Europe and the Former Soviet Union", predicting that between 2007 and 2027 the populations of Georgia and Ukraine will decrease by 17% and 24%, respectively.[97] The World Bank estimates the population of 65 or older citizens in Poland and Slovenia will increase from 13% to 21% and 16% to 24%, respectively between 2005 and 2025.[83]

See also

- Aging of the United States

- Aging of Canada

- Aging of Japan

- Aging of South Korea

- Aging of China

- Aging of Australia

- Russian Cross

- Demographics of Europe

- List of European countries by population growth rate

- Political demography

- Population decline

- Retirement in Europe

General:

- List of sovereign states and dependencies by total fertility rate

- Population ageing

- Population pyramid

- Sub-replacement fertility

- World population

- Replacement migration

Demographic economics:

References

- Notes

- ^ a b Giuseppe Carone and Declan Costello (2006). "Can Europe Afford to Grow Old?". International Monetary Fund Finance and Development magazine. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Population structure and ageing - Statistics Explained". Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Iburg, KM; Charalampous, P; Allebeck, P (24 November 2022). "Burden of disease among older adults in Europe—trends in mortality and disability, 1990–2019". European Journal of Public Health. 33 (1): 121–126. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckac160. PMC 9897992. PMID 36421036.

- ^ "Europe's Shrinking, Aging Population". Stratfor.com. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Europe's Aging Population Faces Social Problems Similar to Japan's". Goldsea Asian American Daily. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ European Commission (2014). "Population Aging in Europe: Facts, Implications, and Policies.". Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Richard Bernstein (29 June 2003). "Aging Europe Finds Its Pension Is Running Out". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Paul S. Hewitt (2002). "Depopulation and Aging in Europe and Japan: The Hazardous Transition to a Labor Shortage Economy". International Politics and Society. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ a b Weeks, John Robert (2012). Population : an introduction to concepts and issues (11th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage learning. ISBN 9781111185978. OCLC 697596943.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "World Population Ageing 2017". United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ Artzrouni, M; Easterlin, R (1982). "Birth History, Age Structure, and Post World War II Fertility in Ten Developed Countries: An Exploratory Empirical Analysis". Genus. 38 (3–4): 81–99. PMID 12312903.

- ^ a b c "Europe's Shrinking, Aging Population". Stratfor.com. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Europeans Credit EU with Promoting Peace and Prosperity, but Say Brussels is Out of Touch with Its Citizens". 19 March 2019.

- ^ Eurostat, Population Projections, European Commission, 2012

- ^ Steyn, Mark (2006) America Alone: The End of the World As We Know It Washington D.C., Regnery Publishing. On pages 10 and 54, birth rates among people of European ancestry populations in various nations are indicated that show all populations of European ancestry are reproducing at an average birth rate of only about 1.4, almost half the replacement rate of 2.1, and thus their population has a negative (declining) growth rate that will decline by almost half every generation.

- ^ a b "Childless Europe: What Happens to a Continent When it Stops Making Babies?" New York Times Magazine Sunday, 29 June 2008

- ^ Himmelfarb, Milton, and Victor Baras (eds). 1978. Zero Population Growth-For Whom?: differential fertility and minority group survival. Westport, CT: Praeger; Leuprecht, C. 2011. "'Deter or Engage?:Demographic Determinants of Bargains in Ethno-Nationalist Conflicts'." in Political Demography: identity, conflict and institutions ed. J. A. Goldstone, E. Kaufmann and M. Toft. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Press Archived 26 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lodge, M. and Hood, C. (2011) Into an age of multiple austerities?: public management and public service bargains across OECD countries. Governance, 25 (1). pp. 79-101. ISSN 0952-1895 DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01557.x

- ^ Coole, D. (2012) Reconstructing the elderly: a critical analysis of pensions and population policies in an era of demographic ageing. Contemporary Political Theory 11 (1), pp. 41-67. ISSN 1470-8914. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/cpt.2011.12

- ^ Timonen, V. (2008). Ageing Societies: A Comparative Introduction. Open University Press.

- ^ Gruber, J. and Wise, D. (2001). An international perspective on policies for an aging society, National Bureau of Economic Research, 8103, DOI: 10.3386/w8103.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Timonen, V. (2008). Ageing Societies: A Comparative Introduction. Open University Press.

- ^ Strauss, S. & Trommer, K. (2018). Productive Ageing Regimes in Europe: Welfare State Typologies Explaining Elderly Europeans’ Participation in Paid and Unpaid Work. Population Ageing , 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-017-9184-4

- ^ a b c d e Vlandas, T., McArthur, D., & Ganslmeier, M. (2021). Ageing and the economy: a literature review of political and policy mechanisms. Political Research Exchange, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2021.1932532

- ^ Bhatti, Y. & Hansen K. M. (2012). The Effect of Generation and Age on Turnout to the European Parliament – How turnout will continue to decline in the Future, Electoral Studies, 31(2), 262-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2011.11.004

- ^ Tilley, J. (2002). Political Generations and Partisanship in the UK, 1964-1997, Journal of Royal Statistical Society. Serie A: Statistics in Society, 165(1), 121-135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-985X.00628

- ^ Busemeyer, M.R., Goerres, A. and Weschle, S. (2009). Attitudes towards redistributive spending in an era of demographic ageing: the rival from age and income in 14 OECD countries, Journal of Eureopan Social Policy, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928709104736

- ^ Cattaneo, M.A. and Wolter, S.C. (2009). Are the Elderly a Threat to Educational Expenditures?, European Journal of Political Economy, 25(2), 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.10.002

- ^ Goerres, A. and Tepe, M. (2010). Age-Based Self-Interest, Intergenerational Solidarity and the Welfare State: A Comparative Analysis of Older People’s Attitudes Towards Public Childcare in 12 OECD Countries, European Journal of Political Research, 49(6), 819-851, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01920.x

- ^ Parth, A.-M., & Vlandas, T. (2022). The welfare state and support for environmental action in Europe, Journal of European Social Policy, 32(5), 531-547. https://doi.org/10.1177/09589287221115657

- ^ Fernandez, J.J. and Jaime-Castillo, A.M. (2012). Positive or Negative Policy Feedback? Explaining Popular Attitudes Towards Pragmatic Pension Policy Reforms, European Sociological Review, 29(4), 803-815. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs059

- ^ Lynch, J. and Myrskyla, M. (2009). Always the Third Rail?: Pension Income and Policy Preferences in European Democracies, Comparative Political Studies, 42(8), 1068-1097. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009331722

- ^ Muuri, A. (2010). The Impact of the Use of the Social Welfare Services or Social Security Benefits on Attitudes to social Welfare Policies, International Journal of Social Welfare, 19(2), 131-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2009.00641.x

- ^ Busemeyer, M.R., Goerres, A. and Weschle, S. (2009). Attitudes towards redistributive spending in an era of demographic ageing: the rival from age and income in 14 OECD countries, Journal of Eureopan Social Policy, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928709104736

- ^ Vlandas, T. (2018). Grey power and the Economy: Aging and Inflation Across Advanced Economies. Comparative Political Studies, 51(4), 514-552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017710261

- ^ a b Vlandas, T. (2023). From Gerontocracy to Gerontonomia: The Politics of Economic Stagnation in Ageing Democracies. The Political Quarterly, 94(3), 452-461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13301

- ^ Lodge, M. and Hood, C. (2011) Into an age of multiple austerities?: public management and public service bargains across OECD countries. Governance, 25 (1). pp. 79-101. ISSN 0952-1895 DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01557.x

- ^ Coole, D. (2012) Reconstructing the elderly: a critical analysis of pensions and population policies in an era of demographic ageing. Contemporary Political Theory 11 (1), pp. 41-67. ISSN 1470-8914. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/cpt.2011.12

- ^ a b c Foster, L. and Walker, A. (2013). Gender and active ageing in Europe, European Journal of Ageing, 10, 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0261-0

- ^ a b Hartlapp, M. and Schmid, G. (2013). Labour market Policy for ‘Active Ageing’ in Europe: Expanding the Options for Retirement Transitions, Journal of Social Policy, 37(3), 409-431. doi:10.1017/S0047279408001979

- ^ Vodopivec, M., Finn, D., Laporsek, S., Vodopivec, M. and Cvörnjek, N. (2019). Increasing Employment of Older Workers: Addressing Labour Market Obstacles, Journal of Population Ageing, 12, 273-298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-018-9236-4

- ^ a b c d e Hinrichs K. (2020) Recent pension reforms in Europe: More challenges, new directions. An overview. Soc Policy Adm. 2021;55:409–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12712

- ^ Jensen, C., Arndt, C., Lee, S., & Wenzelburger, G. (2018). Policy instruments and welfare state reform. Journal of European Social Policy, 28(2), 161-176.

- ^ Eurofound. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Retirement. Retieved from https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/topic/retirement#:~:text=In%20recent%20years%2C%20some%20Member,to%20continue%20working%20for%20longer

- ^ Natali, D., Spasova, S., & Vanhercke, B. (2016). Retirement regimes for workers in arduous or hazardous jobs in Europe. A study of national policies. ESPN European Commission, 1, 1-54.

- ^ a b c Coole, D. (2012) Reconstructing the elderly: a critical analysis of pensions and population policies in an era of demographic ageing. Contemporary Political Theory 11 (1), pp. 41-67. ISSN 1470-8914. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/cpt.2011.12

- ^ Stern Review. (2006) The economics of climate change, Taylor-Gooby, P. (ed.) (2004) New Risks, New Welfare. The Transformations of the European Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ United Nations. (2008). Guide to the national implementation of the Madrid international plan of action on ageing. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- ^ United Nations. (2008). The Second World Assembly on Ageing. Retrieved from https://unece.org/DAM/pau/MIPAA.pdf

- ^ United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). (n.d.). Ageing Policies Database. Retrieved from https://ageing-policies.unece.org/

- ^ World Health Organization (WHO). (n.d.). Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Retrieved from https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHO-Active-Ageing-Framework.pdf

- ^ Rodolfo Luzio and Jianping Zhou (2007). "March 2007, IMF Country Report No. 07/88, Belgium: Selected Issues" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Rudolf Luzio (2007). "Belgium: Time to Shift to Higher Gear". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ THL.fi (2018). "Ageing Policy". THL.fi. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ OECD (2020). "OECD recommends Finland to do more to help older people stay in work". OECD. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Shleutker, Elina (2013). "Väestön ikääntyminen ja hyvinvointivaltio Mitä vaihtoehtoja meillä on?" (PDF). Julkari.fi. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Statistics Finland (2019). "The decline in the birth rate is reflected in the population development of areas". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Caroline Wyatt (16 January 2007). "France claims EU fertility crown". BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ "France has a baby boom". International Herald Tribune. 2005. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ "The World Factbook 2009". Washington DC: Central Intelligence Agency. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ^ "The French Social Security System". Cleiss.fr. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ 14 Jan 2014 (Reuters) "French birth rate falls below two children per woman"

- ^ "Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht".

- ^ a b c "Germany Fertility Rate 1950-2020". Washington DC: Central Intelligence Agency. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ^ Destatis (3 May 2005). "Im Jahr 2060 wird jeder Siebente 80 Jahre oder älter sein" (in German). Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ "Demographic Transition Model". Barcelona Field Studies Centre. 27 September 2009. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Unknown (2000). "Aging Populations in Europe, Japan, Korea, Require Action". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Empty playgrounds in an aging Italy". International Herald Tribune. 2006. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Leszko, Magdalena; Zając-Lamparska, Ludmila; Trempala, Janusz (1 October 2015). "Aging in Poland". The Gerontologist. 55 (5): 707–715. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu171. ISSN 0016-9013. PMID 26315315.

- ^ "Poland's Taking a Stand Against Europe's Demographic Decline". Bloomberg.com. 9 November 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ "Esperança de vida à nascença por sexo". Pordata. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Schroots, J. J. F.; Rocío Fernández Ballesteros; Georg Rudinger (1999). Aging in Europe. pp. 101–102.

- ^ Schroots, J. J. F.; Rocío Fernández Ballesteros; Georg Rudinger (1999). Aging in Europe. pp. 107–108.

- ^ "National population projections, fertility assumptions: 2018-based - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Births in England and Wales - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Vital Events Reference Tables 2019" (PDF). National Records of Scotland. 23 June 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Overview of the UK population - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "National population projections - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Ratio of people aged 15-64 to people aged over 65 years, 2015 and 2050". doi:10.1787/888933867607. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "National life tables – life expectancy in the UK - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Russian Birth Rate above Regional Average Archived 18 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Euromonitor International, retrieved on 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b "The Demographic Transition in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ a b Steven Eke (23 June 2005). "Russia's population falling fast". BBC News. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Russia sees first population increase in 15 years BBC Retrieved on 18 February 2009

- ^ 2009 demographic figures Rosstat Retrieved on 18 February 2010

- ^ Historic population growth of Russia Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 May 2009

- ^ Population of Russia 1989–2008 Retrieved on 26 May 2009

- ^ Newsru, Население России за пять лет уменьшилось на 3,2 миллиона до 142 миллионов человек, 19.Oct.2007 Retrieved same date

- ^ Mortality Country Fact Sheet 2006 WHO

- ^ Nicholas Eberstadt (2004). "The Emptying of Russia". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ World Bank report on Russia's demography World Bank Retrieved on 3 May 2008

- ^ Masha Stromova (12 September 2007). "Have Sex, Make A Baby, Win A Car?". CBS News. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Демография Archived 25 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fred Weir (2002). "Russia's population decline spells trouble". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Russia cracking down on illegal migrants". International Herald Tribune. 15 January 2007.

- ^ "East: 'If Countries Don't Act Now, It's Going To Be Too Late'". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

Further reading

- Kunisch, Sven; Boehm, Stephan A.; Boppel, Michael (eds): From Grey to Silver: Managing the Demographic Change Successfully, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-15593-2

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, Diego; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, Vicente (eds): Environmental Gerontology in Europe and Latin America. Policies and perspectives on environment and aging. Nueva York: Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-3-319-21418-4.

- Scholefield, Anthony. The Death of Europe: How Demographic Decline Will Destroy the European Union. 2000.

External links

- FLASH POINTS AND TIPPING POINTS: Security Implications of Global Population Changes, 2005–2025

- CoViVE Research Consortium on Population Aging in Flanders and Europe

- The Emptying of Russia

- Replacement Migration: Is it a solution for Russia?

- Some EU nations offer benefits for births

- European Countries Try to Stimulate Higher Birth Rates[permanent dead link]

- Norway's welfare model 'helps birth rate'

- Dossier "The Aging Society" – Goethe-Institut