3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name 1-azabicyclo[2.2.2]octan-3-yl hydroxy(diphenyl)acetate | |||

| Other names BZ EA-2277 CS-4030 QNB | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.060 | ||

| MeSH | Quinuclidinyl+benzilate | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C21H23NO3 | |||

| Molar mass | 337.419 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White crystalline powder | ||

| Melting point | 164 to 165 °C (327 to 329 °F; 437 to 438 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 322 °C (612 °F; 595 K) | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

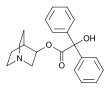

3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate (QNB) (IUPAC name 1-azabicyclo[2.2.2]octan-3-yl hydroxy(diphenyl)acetate; US Army code EA-2277; NATO code BZ; Soviet code Substance 78[1]) is an odorless and bitter-tasting military incapacitating agent.[2] BZ is an antagonist of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors whose structure is the ester of benzilic acid with an alcohol derived from quinuclidine.

Physicochemical characteristics

BZ is a white crystalline powder with a bitter taste. It is odorless and nonirritating with delayed symptoms several hours after contact.[2][3] It is stable in most solvents, with a half-life of three to four weeks in moist air; even heat-producing munitions can disperse it. It is extremely persistent in soil and water and on most surfaces. BZ is soluble in water, soluble in dilute acids, trichloroethylene, dimethylformamide, and most organic solvents, and insoluble with aqueous alkali.[3][4]

Effects

As a powerful anticholinergic agent, BZ produces a syndrome of effects known as the anticholinergic toxidrome: these include both psychological and physiological effects, with the most incapacitating effect being a state of delirium characterized by cognitive dysfunction, hallucinations, and inability to perform basic tasks. The usual syndrome of physical anticholinergic effects are also present, including mydriasis (potentially to the point of temporary blindness), tachycardia, dermal vasodilation, xerostomia and hyperthermia.[5] The readily-observable symptoms of the anticholinergic toxidrome are famously characterized by the mnemonic "Mad as a hatter, red as a beet, dry as a bone and blind as a bat" (and variations thereof).[6]

Toxicity

Based on data from more than 500 reported cases of accidental atropine overdose and deliberate poisoning, the median lethal oral dose is estimated to be approximately 450 mg (with a shallow probit slope of 1.8). Some estimates of lethality with BZ have been grossly erroneous, and ultimately the safety margin for BZ is inconclusive due to lack of human data at higher dosage ranges, though some researchers have estimated it to be 0.5 to 3.0 mg/kg and an LD01 is 0.2 to 1.4 mg/kg (Rosenblatt, Dacre, Shiotsuka, & Rowlett, 1977).[7]

Treatment

Antidotes for BZ include 7-MEOTA, which can be administered in tablet or injection form. Atropine and tacrine (THA) have also been used as treatments, THA having been shown to reduce the effects of BZ within minutes.[8][9] Some military references suggest the use of physostigmine to temporarily increase synaptic acetylcholine concentrations.[2]

History

Invention and research

BZ was invented by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Hoffman-LaRoche in 1951.[10] The company was investigating anti-spasmodic agents, similar to tropine, for treating gastrointestinal ailments when the chemical was discovered.[10] It was then investigated for possible use in ulcer treatment, but was found unsuitable. At this time the United States military investigated it along with a wide range of possible nonlethal, psychoactive and psychotomimetic incapacitating agents including psychedelic drugs such as LSD and THC, dissociative drugs such as ketamine and phencyclidine, potent opioids such as fentanyl, as well as several glycolate anticholinergics.[11][12] By 1959, the United States Army showed significant interest in deploying it as a chemical warfare agent.[10] It was originally designated "TK", but when it was standardized by the Army in 1961, it received the NATO code name "BZ", the Chemical Corps initially referred to BZ as CS4030, then later as EA 2277.[7][10] The agent commonly became known as "Buzz" because of this abbreviation and the effects it had on the mental state of the human volunteers intoxicated with it in research studies at Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland.[10] As described in retired Army psychiatrist James Ketchum's autobiographical book Chemical Warfare: Secrets Almost Forgotten (2006), work proceeded in 1964 when a general envisioned a scheme to incapacitate an entire trawler with aerosolized BZ; this effort was dubbed Project DORK.[13] BZ was ultimately weaponized for delivery in the M44 generator cluster and the M43 cluster bomb, until all such stocks were destroyed in 1989 as part of a general downsizing of the US chemical warfare program.

In 2022 a documentary film, Dr Delirium and The Edgewood Experiments, was broadcast on Discovery+, featuring an interview with Ketchum not previously shown.[14]

Use and alleged use

In February 1998, the British Ministry of Defence accused Iraq of having stockpiled large amounts of a glycolate anticholinergic incapacitating agent known as ‘Agent 15’.[15] Agent 15 is an alleged Iraqi incapacitating agent that is likely to be chemically identical to BZ or closely related to it. Agent 15 was reportedly stockpiled in large quantities prior to and during the Persian Gulf War. However, after the war the CIA concluded that Iraq had not stockpiled or weaponized Agent 15.[a][17]

According to Konstantin Anokhin, professor at the Institute of Normal Physiology in Moscow, BZ was the chemical agent used to incapacitate terrorists during the 2002 Nord-Ost siege, but at least 115 hostages perished due to overdose;[18] but many other agents have also been proposed, and none definitively confirmed.

In January 2013, an unidentified U.S. administration official, referring to an undisclosed U.S. State Department cable, claimed that "Syrian contacts made a compelling case that Agent 15, a hallucinogenic chemical similar to BZ,[19] was used in Homs".[20][21] However, in response to these reports a U.S. National Security Council spokesman stated,

The reporting we have seen from media sources regarding alleged chemical weapons incidents in Syria has not been consistent with what we believe to be true about the Syrian chemical weapons program.[17][21]

Legality

BZ is listed as a Schedule 2 compound by the OPCW (Szinicz, 2005).[22]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "We assess that Iraq never went beyond research with Agent 15 – a hallucinogenic chemical similar to BZ – or any other psychochemical. Agent 15 became an issue after a 9 February 1998 British press release claimed that the UK had information, thought to be reliable, that Iraq had large quantities of this chemical agent in the 1980s. UNSCOM and intelligence information indicated that Iraq researched a number of psychochemicals, including Agent 15, BZ, and PCP; however, UNSCOM indicated it saw no evidence of Iraqi importation of large quantities, weaponization, procurement of militarily significant quantities of precursors, or industrial production of these agents."[16]

References

- ^ Conant, Eve (22 November 2002). "More Questions Than Answers". Newsweek. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ a b c QNB: Incapacitating Agent. Emergency Response Safety and Health Database. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Accessed April 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Gupta, Ramesh C. (21 January 2015). Handbook of toxicology of chemical warfare agents (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-12-800494-4. OCLC 903965588.

- ^ US Army FM 3-9

- ^ Committee on Acute Exposure Guideline Levels; Committee on Toxicology; Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology; Division on Earth and Life Studies; National Research Council. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013 Apr 26.

- ^ Ramjan KA; Williams AJ; Isbister GK; Elliott EJ (November 2007). "'Red as a beet and blind as a bat' Anticholinergic delirium in adolescents: lessons for the paediatrician". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 43 (11): 779–780. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01220.x. PMID 17924941. S2CID 37914161.

- ^ a b Goodman, Ephraim (2010). Historical contributions to the human toxicology of atropine : behavioral effects of high doses of atropine and military uses of atropine to produce intoxication. Wentzville, Missouri: Eximdyne. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-9677264-3-4. OCLC 858939565.

- ^ Gupta, Ramesh C. (21 January 2015). Handbook of toxicology of chemical warfare agents (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-12-800494-4. OCLC 903965588.

- ^ Goodman, Ephraim (2010). Historical contributions to the human toxicology of atropine: behavioral effects of high doses of atropine and military uses of atropine to produce intoxication. Wentzville, Missouri: Eximdyne. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-9677264-3-4. OCLC 858939565.

- ^ a b c d e Kirby, Reid. "Paradise Lost: The Psycho Agents", The CBW Conventions Bulletin, May 2006, Issue no. 71, pp. 2-3, accessed December 11, 2008.

- ^ Possible Long-Term Health Effects of Short-Term Exposure To Chemical Agents, Volume 2: Cholinesterase Reactivators, Psychochemicals and Irritants and Vesicants. (1984)

- ^ Ketchum - Chemical Warfare: Secrets Almost Forgotten Archived 2022-10-22 at the Wayback Machine (2006)

- ^ "Army's Hallucinogenic Weapons Unveiled". Wired. April 2007. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Simonpillai, Radheyan (9 June 2022). "'It affected a great number of people': inside the world of shocking military drug experiments". The Guardian.

- ^ Colin Brown; Ian Burrel (10 February 1998). "Iraqi 'zombie gas' arsenal revealed". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 2011-05-13.

- ^ Chemical Warfare Agent Issues (Report). Intelligence Update. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. April 2002. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ a b Lewis, Jeffrey (25 January 2013). "Why everyone's wrong about Assad's zombie gas". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ "Hostages given military's nerve gas antidote". The Guardian. 28 October 2002.

- ^ "Iraqi Chemical Agents and Their Effects". Chemical Warfare Agent Issues (Report). Intelligence Update. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. April 2002. Archived from the original on 2019-04-14. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ Rogin, Josh (15 January 2013). "Secret State Department cable: Chemical weapons used in Syria". Foreign Policy The Cable. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ a b "U.S. plays down media report that Syria used chemical weapons". Reuters. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Valdez, Carlos A.; Leif, Roald N.; Hok, Saphon; Hart, Bradley R. (2017-07-25). "Analysis of chemical warfare agents by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: methods for their direct detection and derivatization approaches for the analysis of their degradation products". Reviews in Analytical Chemistry. 37 (1). doi:10.1515/revac-2017-0007. ISSN 2191-0189. S2CID 103245582.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army.

External links

- Erowid—BZ Vault

- eMedicine—3-Quinuclidinyl Benzilate Poisoning

- Possible Abuse of BZ by Insurgents in Iraq, Defense Tech blog, December 2005.

- Center for Disease Control—BZ Incapacitating Agent

- Kirby, Reid. Paradise Lost: The Psycho Agents, The CBW Conventions Bulletin, v.71, May 2006, p.1.

- Department of Defense—Agent BZ use in Hawaii April through June 1966