Actions of the Bluff, 1916

| The Bluff | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First World War | |||||||||

The Bluff, St Eloi | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Erich von Falkenhayn | Douglas Haig | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 2 regiments | 2 brigades | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

14–18 February: 329 2 March: 908 |

14–17 February: 1,294 2–4 March:1,622 | ||||||||

The Actions of the Bluff were local operations in 1916 carried out in Flanders during the First World War by the German 4th Army and the British Second Army. The Bluff is a mound near St Eloi, south-east of Ypres in Belgium, created from a spoil heap made during the digging of the Ypres–Comines Canal before the war. From 14 to 15 February and on 2 March 1916, the Germans and the British fought for control of the Bluff, the Germans capturing the mound and defeating counter-attacks only for the British to recapture it and a stretch of the German front line, after pausing to prepare a set-piece attack.

The fighting at the Bluff was one of nine sudden attacks for local gains made by the Germans or the British between the appointment of Sir Douglas Haig as commander in chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), and the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. The BEF was at a tactical disadvantage, on low boggy ground, easily observed from German positions. A retirement to more defensible ground was impossible but rather than conserving manpower and resources with a tacit truce, the British kept an active front and five of the German local attacks in the period were retaliation for three British set-piece attacks.

The Germans had better weapons and with a homogenous army, could transfer troops and equipment along the Western Front easier than the Franco–British. The German army still had many pre-war trained officers NCOs and soldiers; the British wartime volunteers gained experience in minor tactics but success usually came from firepower; in the underground war, the BEF tunnellers overtook the Germans in technological ability and ambition. Capturing a portion of the opposing front line proved possible but holding it depended on the opponent. When the Bluff was captured, the British retook it; at the Battle of Mont Sorrel Mt Sorrel and Tor Top were retaken by the Canadians and British gains at St Eloi and Vimy Ridge were lost to German attacks. Had the British occupied the front less densely, more training could have taken place and the wisdom of each policy was debated at the time and since.

Background

Ypres district

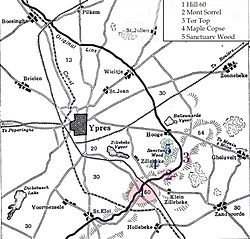

Ypres is overlooked by Kemmel Hill to the south-west and from the east by low hills running south-west to north-east with Wytschaete (Wijtschate), Hill 60 to the east of Verbrandenmolen, Hooge, Polygon Wood and Passchendaele (Passendale). The high point of the ridge is at Wytschaete, 7,000 yd (4.0 mi; 6.4 km) from Ypres, while at Hollebeke the ridge is 4,000 yd (2.3 mi; 3.7 km) distant and recedes to 7,000 yd (4.0 mi; 6.4 km) at Polygon Wood. Wytschaete is about 150 ft (46 m) above the plain; on the Ypres–Menin road at Hooge, the elevation is about 100 ft (30 m) and 70 ft (21 m) at Passchendaele. The rises are slight apart from the vicinity of Zonnebeke, which has a gradient of 1:33. From Hooge and to the east, the slope is 1:60 and near Hollebeke, it is 1:75; the heights are subtle but have the character of a saucer lip around Ypres. The main ridge has spurs sloping east and one is particularly noticeable at Wytschaete, which runs 2 mi (3.2 km) south-east to Messines (Mesen) with a gentle slope to the east and a 1:10 decline to the west. Further south is the muddy valley of the Douve River, Ploegsteert Wood (Plugstreet to the British) and Hill 63. West of Messines Ridge is the parallel Wulverghem (Spanbroekmolen) Spur; the Oosttaverne Spur, also parallel, is to the east. The general aspect south of Ypres is of low ridges and dips, gradually flattening to the north into a featureless plain.[1]

Possession of the higher ground to the south and east of Ypres gives ample scope for ground observation, enfilade fire and converging artillery bombardments. An occupier has the advantage of artillery deployments and the movement of reinforcements, supplies and stores being screened from view. The ridge had woods from Wytschaete to Zonnebeke, giving good cover, some being of notable size like Polygon Wood and those later named Battle Wood, Shrewsbury Forest and Sanctuary Wood. The woods usually had undergrowth but the fields in gaps between the woods were 800–1,000 yd (730–910 m) wide and devoid of cover. Roads in this area were usually unpaved, except for the main ones from Ypres, ribboned with occasional villages and houses. The lowland west of the ridge was a mixture of meadows and fields, with high hedgerows dotted with trees, cut by streams and ditches emptying into canals. The main road to Ypres from Poperinge to Vlamertinge is in a defile, easily observed from the ridge.[2]

The Bluff

Spoil banks had been created during the digging of the Ypres–Comines Canal, connecting the Yser lowlands with the Lys river valley. The canal cutting runs through a low point between Messines Ridge and the higher ground south-east of Ypres, about 1.5 mi (2.4 km) east of St Eloi and near Voormezele. At this point the canal is 120 ft (37 m) wide, in a cutting made higher by 20–30 ft (6.1–9.1 m) banks, extending on the north side to a feature marked on British maps as the Bluff and called the Grosse Bastion or Kanal Bastion by the Germans. The Bluff was 30 ft (9.1 m) high, steep on the west side, with a gentle slope to the east and one of the best vantage points in the Ypres Salient. To the north, the ground rises for 0.75 mi (1.2 km) to Hill 60 and Hooge.[3] After the First Battle of Ypres in 1914, the front line ran at a right angle across the canal, which was still full of water. The British front line on the north bank ran here, just east of the Bluff. No man's land was about 150 yd (140 m) wide and narrowed to about 40 yd (37 m) opposite a German salient about 400 yd (370 m) north, called the Bean by the British and Der Helm by the Germans.[4]

Mining

In the spring of 1915, there was constant underground fighting in the Ypres Salient at Hooge, Hill 60, Railway Wood, Sanctuary Wood, St Eloi and the Bluff, which required new drafts of British tunnellers for several months after the formation of the first eight Tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers.[5] During October and November, the Germans blew two mines under the British lines about 150 yd (140 m) north of the canal.[4] In November, John Norton-Griffiths proposed to sink 20 or 30 shafts, about 50–70 yd (46–64 m) apart, into the blue clay from the Bluff to St Eloi.[6] In late December, the 27th Württemberg Division (General Graf von Pfeil und Klein-Ellguth) was transferred from the Argonne to Flanders to reform the XIII Württemberg Corps (General Theodor von Watter) with the 26th Württemberg Division and took over part of the line on 6 January 1916. The Württembergers relieved the 30th Division in about 2 mi (3.2 km) of the front line from the Ypres–Comines Canal to Zillibeke, south of the positions of the 26th Württemberg Division. The division found the defences in good repair and well-drained, although mostly sandbag breastworks rather than trenches. There was a vulnerable spot at the south end of the line, where the Bluff overlooked the German defences. Previously a mine had been exploded under the Bluff but to no effect and the division began a greater mining effort.[7] A bigger mine was detonated on the night of 21/22 January but all this achieved was a crater about 100 yd (91 m) wide, which the British occupied and made into another defensive position.[4] After the big mine explosion of 21/22 January the British fortified the front lip of the crater and the 172nd Tunnelling Company was diverted from its mining at St Eloi to dig a defensive mine system to prevent the Germans trying again; waterlogging and the loose soil along the canal back caused the miners much difficulty.[4]

Prelude

German offensive preparations

As part of the German plan for the Battle of Verdun (21 February – 18 December 1916), the German armies on the Western Front were ordered to divert attention from the 5th Army with line straightening operations and giving the impression that reinforcements had arrived. From 8 to 19 February, the 4th Army (Generaloberst [Colonel General] Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg) in Flanders, conducted several operations around the Ypres Salient, with artillery bombardments and bombardments followed by attacks. On 12 February, the Germans attacked near Boesinghe (Boezinge) as the 20th (Light) Division was relieving the 14th (Light) Division and got into the front line, until driven back by a prompt counter-attack, the British suffering 184 casualties. The Germans attacked again during the evening and were repulsed; another attack on 19 February also got into the front line for a short time. On 14 February, after a bombardment and the springing of several small mines, German infantry attacked several times against the 24th Division at Hooge and either side of Sanctuary Wood.[8] The XIII Württemberg Corps commander, Watter, had given orders for a methodical attack at the Bluff by Infantry Regiment 124 (IR 124), despite a judgement from General Berthold von Deimling, the previous corps commander, that the Bluff was easier to capture than to hold.[7]

British defensive preparations

The purpose of the German diversionary operations was unknown to the Second Army (General Horace Smith-Dorrien). Reconnaissance flights by the new II Brigade Royal Flying Corps (RFC) were made more difficult by the bad winter weather but 6 Squadron managed to see enough to report that a German offensive was unlikely. The RFC concentrated on artillery-observation for the British heavy guns and in February arranged a standard call "general artillery action" at which all aircraft stopped routine operations for artillery-observation and reconnaissance sorties. The V Corps (Lieutenant-General Herbert Plumer) front ran from south of St Eloi to Hooge and was held by the 17th (Northern) Division, 50th Division and the 24th Division. The 17th (Northern) Division had relieved the 3rd Division from 5 to 8 February on a 4,000 yd (2.3 mi; 3.7 km) front, either side of the Ypres–Comines Canal, with the 52nd Brigade on the south side responsible for the canal, the Bluff and New Year Trench on the north side and the 51st Brigade further north. The only crossing of the canal was a plank bridge some distance back from New Year Trench and although the rule that a topographical feature going through a position should not be used as a unit boundary was followed, only a platoon of the 10th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers held the Bluff, the rest of the battalion being on the south bank. The 50th Brigade was in V Corps reserve which left only one battalion in reserve for the 17th (Northern) Division.[9]

The 51st Brigade held a 1,300 yd (1,200 m) front with three battalions and one in reserve, half kept ready for an immediate counter-attack if the Bluff was captured. One battalion was moving up to relieve one of the front battalions, its bombers (after complaints from the Grenadier Guards, hand-grenade specialists had been renamed bombers and had recently been issued with steel helmets) and Lewis gunners having arrived on 13 February. During the relief, the Bluff was the responsibility of another brigade and two battalions were mixed up; the brigade machine-gun companies, which had joined the division the day previous, were still behind the front line. On the morning of 14 February, the left flank of the 52nd Brigade at the canal and the fronts of the 51st Brigade and the rest of the V Corps front to the north, were subjected to several bombardments by German heavy artillery and after 3:30 p.m. the shelling of the 51st Brigade and the 24th Division front at Hooge increased. The platoon of the 10th Lancashire Fusiliers on the Bluff took cover in The Tunnel, formerly a German mine gallery from the Bluff to the canal. Trench mortar and howitzer fire, which was usual before an infantry attack led the defenders to request heavy artillery support.[10]

Action

14–16 February

By 5:45 p.m. the British front parapet had been demolished and a mine detonation buried the party sheltering in The Tunnel, killing all but three men; two mines were blown on the left of the 10th Sherwood Foresters (10th Sherwood) on the left of the 51st Brigade. IR 124 attacked on a 0.5 mi (0.80 km) front from the canal to a feature known as the Ravine, a stream parallel to the canal. The British front line was captured by 6:05 p.m. and by 6:32 p.m. all objectives had been taken, apart from a machine-gun post at the junction of trenches 31 and 32.[11] A platoon sent to replace the men trapped in The Tunnel was killed and the Bluff was captured, as were the front trenches of the 10th Sherwood. Some German troops pressed on to the British support trenches but were repulsed. Parties of IR 124 also got into trenches and the Ravine on the left, held by the 8th South Staffordshire. The Germans were also quickly forced back but the two companies reserved for an instant counter-attack on the Bluff were delayed by a command mix-up, the men went forward piecemeal and conducted an indecisive bombing fight with the Germans for the rest of the night.[12]

By 7:30 a.m. IR 124 held the Bluff and the 51st Brigade line from the canal to the Ravine. During the afternoon the 52nd Brigade was relieved of responsibility for the north bank and two battalions of the 50th Brigade were sent forward for a counter-attack against the Bluff. During the night bombing attacks were made but attempts to follow up with infantry failed; at 6:00 a.m. on 16 February, the British commanders accepted that the counter-attacks were futile and that it would take a set-piece attack to dislodge the Germans. Plumer gave the task to troops who knew the ground and on the night of 16/17 February the 76th Brigade (Brigadier-General Ernest Pratt) of the 3rd Division, which had been resting out of the line, took over with attached artillery and engineers from the 51st Brigade and began to consolidate a new line. The ground had been smashed up by artillery-fire and was cut with derelict trenches; the Bluff was enclosed by the canal and a stream on the north side which made the ground swampy. The terraces adjoining the canal limited a frontal approach to an embankment 80 yd (73 m) wide but which tapered to 30 yd (27 m), with no cover and visible from the German defences on the south side of the canal.[12]

17 February – 1 March

The 76th Brigade planned to attack against the width of the lost trenches at dusk, to have the maximum time for consolidation, preferably on 29 February. Both sides kept up the bombardment and German casualties were so severe that IR 124 was relieved from 20 to 22 February by Grenadier Regiment 123 (GR 123), which found that the German defences had been destroyed and had to take post in scraps of trench and shell-holes, living up to the waist in water. Over the nights of 22/23 and 23/24 February, the 76th Brigade was relieved by the 52nd Brigade to rest for the attack and its four battalions were equipped with steel helmets, along with two battalions of the 51st Brigade attached for the operation. The force practised on a replica of the German positions copied from aerial photographs, as the 52nd Brigade laboured on jumping-off trenches in the remnants of a sheltered wood, communication trenches, burying telephone cables and carrying ammunition and stores.[13]

German artillery bombardments slowed the work; stormy weather and then snowfalls from 27 February outlined the new trenches and on 28 February, the attack was put back to 2 March, after the cold and snow ended with a thaw which turned the ground into slush; the following days were cold and wet with sleet and snow.[14] The attackers could not wait for 15 to 18 hours but a dusk attack meant moving up the night before. Pratt wanted a long preparatory bombardment and Brigadier-General Herbert Uniacke, the corps artillery commander, proposed a surprise attack with no preliminary artillery-fire. The commanders agreed on a plan to bombard the German defences until the original zero hour at dusk, cease-fire, move up the attack force overnight and attack after a 90-minute dawn bombardment. No date was set because of the weather and incomplete artillery registration but the attack would occur on the second morning after a day with good enough weather to finish registering the guns.[15] As the front line curved eastwards north of the 17th (Northern) Division, four heavy guns were dug in and camouflaged on Observatory Ridge, to fire along the Germans trenches during the attack.[16] Plumer suggested that the 90-minute bombardment be dispensed with for surprise and at a conference, it was agreed that there should be a bombardment at 5:00 p.m. on 1 March for 45 minutes, then a lift and a barrage to simulate an attack. After cessation of the bombardment, Pratt was to decide at 2:00 a.m. if there was to be a 20-minute bombardment before the attack, depending on the German response.[17]

The British attack was to capture more than had been lost, by digging a new line across a feature known as the Bean to protect a re-entrant in the old front line. The right-hand battalion was to retake New Year Trench, the Bluff and Loop Trench, the central and left-hand battalions to attack further north. Each battalion had attached sections of the 56th and East Riding companies RE and tunnelling parties. A battalion was in support of the right-flank battalion and another support battalion was to be available to all three, with two companies behind the centre battalion and a battalion in reserve. On the far right of the attack, a raiding party was to demolish any German mine shafts found along the canal bank. Nine 1+1⁄2-inch, ten 2-inch, four 3-inch Stokes mortars and three 4-inch Stokes mortars were placed in groups on either side of the canal; the bombardment began on 1 March and the Stokes mortars were able to hit areas that the howitzers could not reach. Observation revealed that nearly all the German defences on the Bluff had been destroyed but trenches to the north had been improved and re-wired. The hurricane bombardment was fired from 5:00 to 5:45 p.m. and an 18-pounder field gun was brought up to the front line on the left flank, to demolish 40 yd (37 m) of the German front line to make an obstacle.[18]

2 March

The attackers were guided forward from 4:15 a.m. and attacked on time at 4:30 a.m. Two minutes later the artillery began a barrage behind the objectives and took the Germans by surprise, except on the left, where a German machine-gun crew cut down two platoons. The waves of infantry easily walked over the remaining wire unopposed. The German sentries at the Bluff were found under cover, expecting the artillery salvo after the usual two-minute pause and the rest of the garrison was in dug-outs in the western face of the large crater.[19] To the north, the attackers overran the objective on the Bean, which they did not recognise, because the trenches had been obliterated. Parties which ventured further forward suffered many casualties and the survivors were pulled back to the objective where consolidation began. Later on, some Germans who had been bypassed opened fire but soon surrendered and 181 prisoners were sent to the rear. On the left flank the British troops were reinforced and by 5:10 a.m. had captured the machine-gun nest. The attackers took 252 prisoners although 47 of them were only taken from the dug-outs at the Bluff after resisting into the evening.[20]

The raiders blew in the gallery in no man's land that led to the Bluff but those from the 172nd Tunnelling Company were killed by machine-gun fire. The German artillery reply began at 9:30 a.m. but the intense fire did not begin until 11:00 a.m., by when the British had emptied their front line and made rapid progress in consolidation. The German artillery continued a high rate of fire until 3:15 p.m. and severely damaged the old and new front lines, which took much work to repair. One of the trenches was named International Trench after the dead from three armies were discovered. GR 123 had been exhausted by the 36-hour preparatory bombardment, which destroyed the German positions. In the evening bombers from GR 123 and parties from IR 124 and IR 127 counter-attacked. The British bombers, with plenty of Mills grenades and supported by many machine-guns were able to repulse the Germans. (Each attacker had carried two grenades and 52,000 more had been dumped close by.)[21]

Aftermath

Analysis

The fighting at the Bluff was one of nine sudden attacks for local gains made by the Germans and the British between the appointment of Sir Douglas Haig as commander in chief of the BEF and the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. After the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915) and the Battle of Loos (25 September – 13 October) and the extension of the British front in early 1916, the BEF was at a tactical disadvantage against the German army, on wetter ground, easily observed from German positions. When the BEF took over more of the Western Front from the French, it was to be held lightly with outposts, while a better line was surveyed further back. The survey revealed that all of the French gains of 1915 would have to be abandoned, a proposal that the French rejected out of hand. For political reasons, giving up ground around Ypres in Belgium was also unacceptable, only an advance could be contemplated to improve the positions of the BEF. Since the French and British anticipated early advances in 1916, there seemed little point in working on defences, when the Germans were building more elaborate defences, except at Verdun. Rather than continue the informal truces that had developed between French and German trench garrisons, the British kept an active front and five of the German local attacks in the period were retaliation for three British set-piece attacks.[22]

In early 1916, the Germans had an advantage in trench warfare equipment, being equipped with more and better hand grenades, rifle grenades and trench mortars. It was easier for the Germans to transfer troops, artillery and ammunition along the Western Front than the Franco-British, who had incompatible weapons and ammunition. A substantial cadre of German pre-war trained officers NCOs and soldiers remained; the British wartime volunteers gained experience in minor tactics but success usually came from machine-guns and the accuracy and quantity of artillery support, not individual skill and bravery. In the underground war, the BEF tunnellers overtook their German counterparts in technological ability and ambition. With sufficient artillery, the capture of a small part of the opponents' line was possible but holding it depended on the response of the opponent. When the Bluff was captured, the British retaliated and retook it and Mount Sorrel and Tor Top were retaken by Canadian troops; when the British took ground at St Eloi and Vimy Ridge, the Germans took it back. The constant local fighting was costly but enabled the mass of inexperienced British troops to gain experience, yet had the front been less densely occupied, more troops could have trained and the wisdom of each school of thought was debated at the time and ever since.[23]

Casualties

| Month | Total |

|---|---|

| December | 5,675 |

| January | 9,974 |

| February | 12,182 |

| March | 17,814 |

| April | 19,886 |

| May | 22,418 |

| June | 37,121 |

| Total | 125,141 |

From 14 to 17 February the 17th (Northern) Division suffered 1,294 casualties including 311 missing and from 2 to 4 March, the attacking battalions suffered 1,622 casualties, 924 men in the 76th Brigade, 3rd Division and 698 in the 17th (Northern) Division.[25][a] From 14 to 18 February, IR 124 suffered 75 fatal casualties, 229 wounded and 25 missing. There were 908 German casualties on 2 March, GR 123 suffering casualties of 41 men killed, 172 wounded and 321 missing.[26]

Subsequent operations

The Germans dug long galleries beneath the Bluff and on 25 July the 1st Company, 24th Pioneers blew a mine under the ridge. The 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company had given warning of the German attempt and the 7th Canadian Battalion occupied the crater before the German infantry arrived. On 29 July, Canadian troops raided the German lines at St Eloi, inflicted about 50 casualties and repulsed a German raid at Hill 60 on 12 August.[27][28] Mining and tunnel warfare continued at the Bluff by tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers.[29] After a prisoner drew a map of the German mine workings, the British dug a deep system under the galleries beyond the German lines. On 11 December, several big camouflets were sprung and the German mine galleries were captured, making it impossible for German tunnellers to retaliate and the area was declared safe.[30] On 7 June 1917, the Germans were driven from the area during the Battle of Messines Ridge.[30] The Germans re-took the Bluff during the Spring Offensive of 1918 and it changed hands for the last time on 28 September 1918, after an attack by the 14th (Light) Division.[31]

Commemoration

The wooded ridge is now a provincial nature reserve and picnic area, Provinciaal Domein Palingbeek.[32] There are three Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) war cemeteries in the area

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Hilliard Atteridge 2003, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d Edmonds 1993, p. 164.

- ^ Barton, Doyle & Vanderwalle 2005, p. 165.

- ^ Jones 2010, pp. 101–103.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1993, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 163–165.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, p. 173.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1993, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 167, 173.

- ^ Hilliard Atteridge 2003, p. 88.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, p. 168.

- ^ Hilliard Atteridge 2003, p. 87.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Hilliard Atteridge 2003, p. 90; Edmonds 1993, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 171–173.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, p. 243.

- ^ a b Hilliard Atteridge 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 167, 172–173.

- ^ Nicholson 1962, p. 154; Jones 2010, p. 143.

- ^ Vijver 2008.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 162–163, 169–172.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1993, p. 172.

- ^ Edmonds 1995, pp. 204–209.

- ^ PWV 2008.

References

Books

- Barton, Peter; Doyle, Peter; Vanderwalle, Johan (2005). Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers' War 1914–1918. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-237-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1995) [1937]. Military Operations France and Belgium: 1918 March–April: Continuation of the German Offensives. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-223-4.

- Hilliard Atteridge, A. (2003) [1929]. History of the 17th (Northern) Division (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: R. Maclehose. ISBN 978-1-84342-581-6.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 59609928. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

Websites

- "Palingbeek" (in Dutch). Provincie West-Vlaanderen. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- Vijver, Sander Van de (2008). "Wereldoorlog I in de Westhoek" [World War I in Westhoek]. The Great War in Flanders Fields. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

Further reading

Books

- Barrie, A. (1981) [1962]. War Underground. War in the Twentieth Century (Star ed.). London: Frederick Muller. ISBN 978-0-352-30970-9.

- Work in the Field Under the Engineer-in-Chief, B. E. F.: Geological Work on the Western Front. The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War, 1914–19. Chatham: The Secretary, Institution of Royal Engineers. 1922. OCLC 613625502. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

Websites

- Baker, Chris. "Fighting at the Bluff". The Long, Long Trail. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- Karel, Roose (3 February 2003). "Cycling Belgium's Waterways: Comines–Ieper". Gamber Net Home. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2008.