7 Iris

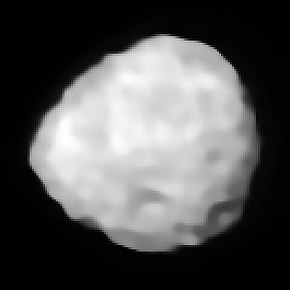

Iris imaged by the Very Large Telescope in 2017[1] | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | John Russell Hind |

| Discovery date | 13 August 1847 |

| Designations | |

| (7) Iris | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈaɪrɪs/[2] |

Named after | Īris |

| Main belt | |

| Adjectives | Iridian /ɪˈrɪdiən, aɪ-/[3] |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics[4] | |

| Epoch 13 September 2023 (JD 2453300.5) | |

| Aphelion | 2.935 AU (439.1 million km) |

| Perihelion | 1.838 AU (275.0 million km) |

| 2.387 AU (357.1 million km) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.22977 |

| 3.69 a (1346.8 d) | |

Average orbital speed | 19.03 km/s |

| 207.9° | |

| Inclination | 5.519° |

| 259.5° | |

| 4 April 2025 | |

| 145.4° | |

| Earth MOID | 0.85 AU (127 million km)[4] |

| Proper orbital elements[5] | |

Proper semi-major axis | 2.3862106 AU |

Proper eccentricity | 0.2125516 |

Proper inclination | 6.3924857° |

Proper mean motion | 97.653672 deg / yr |

Proper orbital period | 3.6865 yr (1346.493 d) |

Precession of perihelion | 38.403324 arcsec / yr |

Precession of the ascending node | −46.447128 arcsec / yr |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 268 km × 234 km × 180 km ± (5 km × 4 km × 6 km)[1] 225 km × 190 km × 190 km[6] |

| 199±10 km[7][8] 214±5 km[1] 199.83±10 km (IRAS)[4] | |

| Flattening | 0.42[a] |

| 538460 km2[b] | |

| Volume | 37153500 km3[b] |

| Mass | (13.5±2.3)×1018 kg[8](13.75±1.3)×1018 kg[1] |

Mean density | 3.26±0.74 g/cm3[8] 2.7±0.3 g/cm3[1] |

Equatorial surface gravity | 0.08 m/s² |

Equatorial escape velocity | 0.131 km/s |

| 7.138843 h (0.2974518 d)[1] | |

Equatorial rotation velocity | 25.4 m/s[b] |

| 0.279[8] 0.2766±0.030[4] | |

| Temperature | ~171 K max: 275 K (+2°C) |

| S | |

| 6.7[9][10] to 11.4 | |

| 5.64[4] | |

| 0.32" to 0.07" | |

7 Iris is a large main-belt asteroid and possible remnant planetesimal orbiting the Sun between Mars and Jupiter. It is the fourth-brightest object in the asteroid belt. 7 Iris is classified as an S-type asteroid, meaning that it has a stony composition.

Discovery and name

Iris was discovered on 13 August 1847, by J. R. Hind from London, UK. It was Hind's first asteroid discovery and the seventh asteroid to be discovered overall. It was named after the rainbow goddess Iris in Greek mythology, who was a messenger to the gods, especially Hera. Her quality of attendant of Hera was particularly appropriate to the circumstances of discovery, as Iris was spotted following 3 Juno by less than an hour of right ascension (Juno is the Roman equivalent of Hera).

Iris's original symbol was a rainbow and a star: ![]() or more simply

or more simply ![]() . It is in the pipeline for Unicode 17.0 as U+1CEC1 (

. It is in the pipeline for Unicode 17.0 as U+1CEC1 (![]() ).[11][12]

).[11][12]

Characteristics

Geology

Iris is an S-type asteroid. The surface is bright and is probably a mixture of nickel-iron metals and magnesium- and iron-silicates. Its spectrum is similar to that of L and LL chondrites with corrections for space weathering,[13] so it may be an important contributor of these meteorites. Planetary dynamics also indicates that it should be a significant source of meteorites.[14]

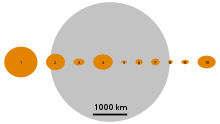

Among the S-type asteroids, Iris ranks fifth in mean diameter after Eunomia, Juno, Amphitrite and Herculina. Its shape is consistent with an oblate spheroid with a large equatorial excavation, suggesting it is a remnant planetesimal. No collisional family can be associated with Iris, likely because the excavating impact occurred early in the history of the Solar System, and the debris has since dispersed.[1]

Brightness

Iris's bright surface and small distance from the Sun make it the fourth-brightest object in the asteroid belt after Vesta, Ceres, and Pallas. It has a mean opposition magnitude of +7.8, comparable to that of Neptune, and can easily be seen with binoculars at most oppositions. At typical oppositions it marginally outshines the larger though darker Pallas.[15] But at rare oppositions near perihelion Iris can reach a magnitude of +6.7 (last time on 31 October 2017, reaching a magnitude of +6.9),[9] which is as bright as Ceres ever gets.

Surface features

A study by Hanus et al. using data from the VLT's SPHERE instrument names eight craters 20 to 40 km in diameter, and seven recurring features of unknown nature that remain nameless due to a lack of consistency and their occurrence on the edge of Iris. The names are Greek names of colors, corresponding to the rainbow as the sign of Iris. It is unknown whether these names are under consideration by the IAU. The other 7 features are labeled A through G.[1]

| Feature | Pronunciation | Greek | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloros | /ˈkloʊrɒs/ | χλωρός | 'green' |

| Chrysos | /ˈkraɪsɒs/ | χρῡσός | 'gold' |

| Cirrhos | /ˈsɪrɒs/ | κιρρός | 'orange'[c] |

| Cyanos | /ˈsaɪənɒs/ | κύανος | 'blue' |

| Erythros | /ˈɛrɪθrɒs/ | ἐρυθρός | 'red' |

| Glaucos | /ˈɡlɔːkɒs/ | γλαυκός | 'grey'[d] |

| Porphyra | /ˈpɔːrfɪrə/ | πορφύρα | 'purple' |

| Xanthos | /ˈzænθɒs/ | ξανθός | 'yellow' |

Rotation

Iris has a rotational period of 7.14 hours. Iris’ north pole points towards the ecliptic coordinates (λ, β) estimated to be (18°, +19°) with a 4° uncertainty (Viikinkoski et al. 2017) or (19°, +26°) with a 3° uncertainty (Hanuš et al. 2019). This gives an axial tilt of 85°,[17] so that on much of each hemisphere, the sun does not set during summer, and does not rise during winter. On an airless body this gives rise to very large temperature differences.

Observations

Iris was observed occulting a star on 26 May 1995, and later on 25 July 1997. Both observations gave a diameter of about 200 km.

In February 2024, water molecules were discovered on 7 Iris, alongside 20 Massalia, marking the first time water molecules were detected on asteroids.[18][19]

See also

Notes

- ^ Flattening derived from the maximum aspect ratio (c/a): , where (c/a) = 0.58±0.07.[8]

- ^ a b c Calculated based on parameters calculated by J. Hanuš et al.[1]

- ^ κιρρός is variously translated. The OED has 'orange-tawny'.[16] The color coding of the proposers in their crater maps, however, is simply orange.

- ^ Or greyish blue-green.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hanuš, J.; Marsset, M.; Vernazza, P.; Viikinkoski, M.; Drouard, A.; Brož, M.; et al. (24 April 2019). "The shape of (7) Iris as evidence of an ancient large impact?". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 624 (A121): A121. arXiv:1902.09242. Bibcode:2018DPS....5040406H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834541. S2CID 119089163.

- ^ "iris". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "iridian". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 7 Iris" (2023-07-08 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "AstDyS-2 Iris Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ Kaasalainen, M.; et al. (2002). "Models of twenty asteroids from photometric data" (PDF). Icarus. 159 (2): 369–395. Bibcode:2002Icar..159..369K. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6907.

- ^ Dudziński, G; et al. (14 October 2020). "Volume uncertainty of (7) Iris shape models from disc-resolved images". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 499 (3): 4545–4560. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa3153. hdl:10261/237568. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b c d e Vernazza, P.; et al. (October 2021). "VLT/SPHERE imaging survey of the largest main-belt asteroids: Final results and synthesis". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 654: A56. Bibcode:2021A&A...654A..56V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202141781. hdl:10261/263281. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ a b Donald H. Menzel & Jay M. Pasachoff (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 391. ISBN 0-395-34835-8.

- ^ "Bright Minor Planets 2006". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 21 May 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bala, Gavin Jared; Miller, Kirk (18 September 2023). "Unicode request for historical asteroid symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. Unicode. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ Unicode. "Proposed New Characters: The Pipeline". unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Ueda, Y.; Miyamoto, M.; Mikouchi, T.; Hiroi, T. (March 2003). Surface Material Analysis of the S-type Asteroids: Removing the Space Weathering Effect from Reflectance Spectrum. 34th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. p. 2078. Bibcode:2003LPI....34.2078U.

- ^ Migliorini, F.; et al. (1997). "(7) Iris: a possible source of ordinary chondrites?". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 321: 652. Bibcode:1997A&A...321..652M.

- ^ Odeh, Moh'd. "The Brightest Asteroids". Jordanian Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ "cirrhosis". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Pearson, Richard (2020). The History of Astronomy. Lulu.com. p. 349. ISBN 9780244866501.

- ^ Arredondo, Anicia; McAdam, Margaret M.; Honniball, Casey I.; Becker, Tracy M.; Emery, Joshua P.; Rivkin, Andrew S.; Takir, Driss; Thomas, Cristina A. (12 February 2024). "Detection of Molecular H2O on Nominally Anhydrous Asteroids". The Planetary Science Journal. 5 (2): 37. Bibcode:2024PSJ.....5...37A. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ad18b8.

- ^ Gamillo, Elizabeth (14 February 2024). "Water molecules identified on asteroids for the first time". Astronomy. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

External links

- Shape model deduced from lightcurve Archived 2004-10-15 at the Wayback Machine (M. Kaasalainen 2002) doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6907

- 2011-Feb-19 Occultation (Durech Model) / (2011 Asteroidal Occultation Results for North America)

- "Discovery of Iris", MNRAS 7 (1847) 299 doi:10.1093/mnras/7.17.299

- JPL Ephemeris

- "Elements and Ephemeris for (7) Iris". Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. (displays Elong from Sun and V mag for 2011)

- 7 Iris at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 7 Iris at the JPL Small-Body Database