57th Medical Detachment

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army.

| 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) | |

|---|---|

57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) Insignia worn by Major Charles L. Kelly | |

| Active | 19 September 1943 – 30 September 1945 23 March 1953 – 15 June 2007 |

| Country | US |

| Branch | Regular Army |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Liberty |

| Nickname(s) | The Original Dustoff |

| Engagements | Vietnam War Operation Urgent Fury Operation Desert Storm Operation Enduring Freedom Operation Iraqi Freedom |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Major Charles L. Kelly |

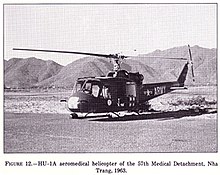

The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) was a US Army unit located at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, which provided aeromedical evacuation support to the Fort Liberty community, while training in its combat support mission. The first helicopter ambulance unit to be fielded the UH-1 Huey helicopter, it was also the first unit to deploy to Vietnam with the UH-1, and the first unit to fly them in combat, in 1962. By the time the detachment redeployed to the continental United States ten years, ten months, and seventeen days later, its crews had evacuated nearly 78,000 patients. The unit's callsign, "Dustoff," selected in 1963, is now universally associated with United States Army aeromedical evacuation units.

- The unit was originally formed as the 57th Malaria Control Unit in 1943 and served in Brazil during World War II. It was later redesignated as the 57th Medical Detachment in 1953 and activated at Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

- The unit was the first to use the UH-1 Huey helicopter for aeromedical evacuation missions. It deployed to Vietnam in 1962 and became the first unit to fly the UH-1 in combat. It also adopted the callsign DUSTOFF in 1963, which became synonymous with Army aeromedical evacuation units.

- The unit's crews evacuated nearly 78,000 patients during its ten-year service in Vietnam. One of its most notable members was Major Charles L. Kelly, who was killed in action in 1964 while attempting to rescue wounded soldiers under heavy fire. He is remembered as the “Father of Dustoff” and his motto “When I have your wounded” is engraved on the DUSTOFF Memorial at Fort Sam Houston.

- The unit also served in Grenada in 1983, where it evacuated 160 casualties during Operation Urgent Fury. It also supported Operation Desert Storm in 1991, where it flew over 600 missions and evacuated over 1,000 patients. It later deployed to Afghanistan in 2002 and Iraq in 2003 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom respectively.

Lineage

- Constituted 1 September 1943 in the Army of the United States as the 57th Malaria Control Unit[1]

- Activated 19 September 1943 at Army Service Forces Unit Training Center, New Orleans, Louisiana[1]

- Reorganized and redesignated 8 April 1945 as the 57th Malaria Control Detachment[1]

- Inactivated 30 September 1945 in Brazil[1]

- Redesignated 23 March 1953 as the 57th Medical Detachment and allotted to the Regular Army[1]

- Activated 6 April 1953 at Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas[1]

- Reorganized and redesignated 1 July 1960 as the 57th Medical Platoon[1]

- Reorganized and redesignated 10 March 1961 as the 57th Medical Detachment[1]

- Reorganized and redesignated 16 November 1992 as the 57th Medical Company[2]

- Inactivated 15 June 2007 at Fort Bragg, North Carolina[3][4]

Honors

Campaign participation credit

World War II

- American Campaign Streamer Without Inscription

- Advisory[1]

- Defense[1]

- Counteroffensive[1]

- Counteroffensive, Phase II[1]

- Counteroffensive, Phase III[1]

- Tet Counteroffensive[1]

- Counteroffensive, Phase IV[1]

- Counteroffensive, Phase V[1]

- Counteroffensive, Phase VI[1]

- Tet 69/Counteroffensive[1]

- Summer-Fall 1969[1]

- Winter-Spring 1970[1]

- Sanctuary Counteroffensive[1]

- Counteroffensive, Phase VII[1]

- Consolidation I[1]

- Consolidation II[1]

- Cease-Fire[1]

Global War on Terror

- To be officially determined

Decorations

- Presidential Unit Citation (Army), Streamer embroidered DONG XOAI[1]

- Valorous Unit Award, Detachment, 57th Medical Company, Streamer not authorized for the company as a whole[5]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered VIETNAM 1964-1965[1]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered VIETNAM 1968[1]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered VIETNAM 1969-1970[1]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered VIETNAM 1970-1971[1]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered VIETNAM 1972-1973[1]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered SOUTHWEST ASIA 1990-1991[6]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered SOUTHWEST ASIA 2003[7]

- Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army), Streamer embroidered IRAQ 2005-2006[8]

- Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Palm, Streamer embroidered VIETNAM 1964[1]

Early history

Fort Sam Houston, Texas

The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance), a General Reserve Unit attached to Headquarters, 37th Medical Battalion (Separate), Medical Field Service School for administration, was further attached for training and operational control. The detachment was activated by General Order Number 10, Headquarters, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, dated 6 April 1953, under TO&E 8–500, Cell: RA, 25 August 1952. By 31 December 1953, the unit had approximately 95 percent of its authorized equipment.[9]

Captain John W Hammett was assigned as the detachment's first commander, and both organized the detachment and trained its newly assigned aviators, who were all newly assigned Medical Service Corps officers fresh out of flight school as well as leading the unit through its first unit tests. The detachment was equipped with H-13E aircraft with exterior mounted litters and litter covers.[2]

The principal activity of this unit consisted of participation in evacuation demonstrations for the Medical Field Service School.[9]

Six officers and 26 enlisted men were assigned to the unit at year end. The total authorized strength of the detachment was 7 officers and 24 enlisted.[9]

Unit training began on 21 September 1953. In accordance with Army Training Program 8–220. Almost immediately many problems were encountered. The principal difficulty was in the maintenance of aircraft, Within a few days after unit training had begun the program was partially abandoned. On 21 October 1953 the detachment was attached to the 37th Medical Battalion (separate), Medical Field Service School, for administration and training. On 6 October 1953 the unit training was again started with certain modifications of the program to allow more time for aircraft maintenance. This training was completed by 31 December 1953.[9]

Effective 7 January 1954 the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) and the 274th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance), assigned to Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas were relieved from attachment to the Medical Field Service School and were attached to Brooks Air Force Base for quarters and rations in accordance with General Order Number 2, Headquarters, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, dated 22 January 1954.[10]

From 28 June through 4 July 1954, all of the aircraft assigned to Brooke Army Medical Center, including those of the 57th and 274th under Hammett's command, were deployed to support flood relief efforts along the Rio Grande River near Langtry, Texas, caused by Hurricane Agnes. The detachments sent seven aircraft to Laughlin Air Force Base and began using it as a base for their search operations. They began by evacuating passengers, luggage, and mail from a Southern Pacific train which had been cut off from ground evacuation, evacuating 85 passengers to the air base, and then again when shortages of drinking water occurred on the base. The aftermath of the storm made flying difficult.[2]

During the period 9 February — 2 March 1955, the 67th Medical Group with attached 603d Medical Company (Clearing)(Separate) and the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) was attached to III Corps at Fort Hood, Texas, for participation in Exercise Blue Bolt. Attached to the Group upon arrival from Fort Riley, Kansas was the 47th Surgical Hospital and 928th Medical Company (Ambulance)(Separate). The Group's assigned mission was to furnish field Army Medical Service support (actual and simulated) to the 1st Armored Division and III Corps. One hundred twenty-eight actual casualties were evacuated to the 603d Medical Company (Clearing). The Ambulance Company evacuated 1025 simulated and actual patients. The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) had the mission of evacuating actual casualties, completing seven pickups with an average patient delivery time of 38 minutes. This was an outstanding accomplishment when measured against the time space factors involved. Twelve hundred patients were routed through an Evacuation Hospital (simulated) established and operated by the Clearing Company.[11]

Effective 10 July 1955, the 67th Medical Group was temporarily reorganized to the 67th Medical Service Battalion (ATFA Provisional) by General Order 21, Brooke Army Medical Center, 7 July 1955. The 32d Medical Depot (Army), 47th and 53d Field Hospitals, and the 82d Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) were also reorganized as ATFA Provisional units by the same authority. On 15 July 1955, Dental Service Team KJ (Provisional #1), Team KJ (Provisional #2), and Medical Detachment (ATFA Provisional Team QA) were activated by Brooke Army Medical Center and attached to the 67th Medical Service Battalion (ATFA). These units were to participate in Exercise Sagebrush during the forthcoming months. The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) was also to participate.[11]

On 1 September 1955 an extensive program of training was placed in effect to prepare all participating units for Sagebrush. Many obstacles in personnel, equipment, and limited training time were encountered. By 15 October after extensive field preparation to include special ATFA testing by Brooke Army Medical Center, these units were considered sufficiently advanced to assume their responsibility though 25% of the newly assigned personnel in the field hospitals lacked the MOS training required. Just prior to leaving, the Group presented the largest mounted review in Brooke Army Medical Center history. Approximately 250 vehicles of all types participated.[11]

On 25 October 1955 all units moved overland to Louisiana. No major accidents occurred. Valuable experience in atomic warfare operations and the handling of mass casualties was received. The hospitals provided medical care and treatment for both actual and simulated casualties. The 67th Medical Service Battalion exercised operational control over attached medical units. The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) received a mission of evacuating actual casualties, reconnaissance, and supply, flying a total of 289 hours. The 82d Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) was further attached to III Corps as a part of the III Corps Aviation Company, executing a total of 165 missions involving 313 flying hours. The 32d Medical Depot (ATFA) supported all units of the Ninth Army during the maneuver. Approximately 10 tons of medical supplies were received, separated, stored, and tallied.[11]

At the conclusion of the exercise, all ATFA Medical units returned to Fort Sam Houston in December with the exception of the 47th Field Hospital which remained in the maneuver area on temporary duty at Fort Polk, Louisiana, rendering medical support to Engineer and Signal Corps units. The unit engaged in the close out phase remained ATFA Provisional at end of 1955.[11]

General Order 42, Brooke Army Medical Center, 13 December 1955, discontinued all returned provisional units as of 14 December. The remainder of the reporting period was spent on ATFA equipment organization, cleaning, and return.[11]

During December 1955, a part of the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) was preparing for departure in January 1956 for Alaska to participate in Exercise Moose Horn. Effort was being made to properly equip this element for the maneuver.[11]

New H-19D aircraft were received by both the 57th and the 82d Medical Detachments beginning in August 1956, with the final aircraft received in the latter part of December. Since the 57th and 82d shared a hangar at Brooks Air Force Base, the 57th painted a circular white background for the red cross on the noses of their aircraft, while the 82d used a square background.[2][12]

In 1957, the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) was assigned to the Office of the Surgeon General, further assigned to Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, for operational control, further assigned to the 67th Medical Group for administration and training and attached to Brooks Air Force Base for rations and quarters.[13]

Fort George G. Meade, Maryland

In October 1957, after hearing rumors all summer, the 57th received a message alerting the unit for a permanent change of station move to Fort George G. Meade, Maryland. On 17 October the movement directive was received and on 30 October the movement order was published by Brooke Army Medical Center. On 5 November the advanced party departed for Fort Meade by private auto. Upon arrival at Fort Meade, the advance party carried out the necessary details prior to the arrival of the detachment's main body. The main body arrived at Fort Meade on 20 November 1957 with the helicopters arriving on 20 November. The aircraft were ferried by other pilots within BAMC. The unit, upon arrival at Fort Meade, remained assigned to the Office of the Surgeon General, attached to the Second United States Army, further attached to Fort Meade, and then further attached to the 68th Medical Group. The mission of the detachment remained training with a secondary mission of supporting Second Army in emergency medical helicopter evacuations.[13]

On 15 February 1968, one of the largest snowstorms in years fell in the DC-Baltimore metropolitan area. Requests for emergency evacuations began coming in shortly after it appeared that the snowfall was to be heavy and that it was bogging down normal transportation facilities. No missions, however, were flown until 18 February 1958. On 17 February Second Army put an emergency plan into effect which placed all pilots, crews and aircraft under their operational control. The missions flown were as follows:[13]

- 18 February 1958 - Evacuated 2 pregnant women, one from a farmhouse north of Gaithersburg, Maryland, the other from a farmhouse near Bealsville, Maryland to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Total flight time - 02:15

- 18 February 1958 - Flew 20 cases of five-in-one rations to Fort Detrick, Maryland from Fort Meade. From Fort Detrick flew to Woodbine, Maryland and evacuated a pregnant woman back to Ft. Detrick. Total flight time - 03:05

- 18 February 1958 - Evacuated 2 patients, both from farmhouses near Chestertown, Maryland to Chestertown Airfield. Total flight time - 02:30

- 18 February 1958 - Evacuated patient from Bozeman, Maryland to Easton, Maryland. Total flight time - 03:20

- 19 February 1958 - Evacuated patient from Lewisdale, Maryland to hospital at Laytonsville, Maryland. Total flight time - 03:10

- 19 February 1958 - Evacuated patient from Sugar Loaf Mountain to Fredrick, Maryland. Total flight time - 02:20

- 19 February 1958 - Delivered fuel to farmhouse near Savage, Maryland. Total flight time - 00:30

- 19 February 1958 - Delivered fuel to farmhouse near Savage, Maryland. Total flight time - 00:45

- 21 February 1958 - Flew 4 photographers to Crystal Beach, Maryland to photograph another mission, Total flight time - 03:30

- 22 February 1958 - Evacuated patient from Smith Island, Maryland to Crisfield Airfield, Maryland. Total flight time - 04:00

- 23 February 1958 - Flew to Chestertown, Maryland to search for 2 lost boys. Bodies of 2 drowned boys were found at Panama by boats. Bodies flown from Panama back to Chestertown. Total flight time - 02:30

The detachment came off of alert status on 26 February 1958 and resumed normal duties. The detachment also participated in 68th Medical Group exercises from 4 February to 7 February, evacuating simulated casualties and setting up operations in the field.[13]

On 23 March another big snow crippled the northeast sector of the country, however the roads were readily cleared. The detachment was put on stand-by alert for medical evacuation, but none materialized.[13]

On 23 March one aircraft flew power lines for the Philadelphia Electric Company around the Coatesville, Pennsylvania area carrying company personnel who were checking for downed power lines.[13]

One helicopter was dispatched on 17 July 1958 to support the 338th Medical Group at Fort Meade. It was used for simulated medical evacuations and orientation flights.[13]

An H-19 was sent to Fort Lee, Virginia, on 24 July 1958 to orient reserve personnel on temporary active duty from the 300th Field Hospital. A simulated evacuation and orientation rides were given. A static display of aircraft and a simulated evacuation were shown to Reserve Officers' Training Corps cadets visiting Fort Meade on 31 July 1958.[13]

A lecture was given to personnel of the 314th Station Hospital at Fort Lee, Virginia on 21 August 1958. A simulated evacuation and orientation rides were given, Normal unit missions completed the month.[13]

On 25 September 1958, a mission of a rather unusual nature was accomplished in an H-19. The Maryland Fish and Game Commission requested that the 57th fly a tubful of live fish from Rock Hall, Maryland to Deep Creek Lake in western Maryland. A noncommissioned officer sat in the "hole" with the fish and dropped oxygen tablets in the water, but to no avail. Of the forty striped bass netted from the Chesapeake Bay, only 4 were alive at the conclusion of the flight. This was the first, and probably last, time fish had been transported in this manner.[13]

On 21 September the 57th went on an overnight field problem on the Fort Meade reservation. The new heliport lighting system was tested for the first time and after quite a bit of practice and resetting the equipment, landings were being made at night quite accurately.[13]

On 7 October, one H-19 was sent to Fort A. P. Hill, Virginia to act on a stand-by basis for possible casualties resulting from field exercises. The 79th Engineer Group and the 13th Field Hospital were practicing field problems prior to taking their Army Training Tests. The 57th had one helicopter on a stand-by basis from 7 October to 25 October 1958, but only one minor casualty resulted and was the only helicopter evacuation. The helicopter did carry a doctor daily on sick call trips and made a few reconnaissance missions.[13]

A flight of two helicopters left Fort Meade on 24 November 1958 to make a proficiency cross-country flight to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The pilots also compared notes on units with their counterparts at Fort Bragg. The flight returned the next day to Fort Meade.[13]

An evacuation flight was accomplished on 6 December 1958. An Army Lieutenant Colonel and his family were in volved in an auto accident at Pulaski, West Virginia and placed in the civilian hospital there. A nurse from the Fort Meade Hospital accompanied the flight. The helicopter arrived back at Fort Meade at 1915 hours with Lieutenant Colonel and his wife, where an ambulance brought them to the Fort Meade Hospital. Total flight time logged that day was 07:35 hours.[13]

On 10 December 1958 a Tuberculosis patient was flown from the Fort Meade Hospital to Valley Forge General Hospital.[13]

The month of January 1959 proved to be quite uneventful until 2000 hours on the 27th. At that time the detachment commander received a call at home from the Second Army Aviation Section. The detachment was requested to leave the next morning for Meadeville, Pennsylvania to fly a demolition team, equipment, photographers and the Second Army Public Information Officer. An ice jam on French Creek was threatening to flood the town if another rainfall fell. Meadeville had been crippled by a flood two days before causing $5 million worth of damage. The flood waters had receded, but unless the ice could be blasted from the creek the town would be flooded all over again. Three of the unit's H-19s departed Fort Meade at 0845 hours, 28 January 1959 with six demolition men from the 19th Engineer Battalion, two photographers from the 67th Signal Battalion and the Second Army Public Information Office. Also on the flight were three crew chiefs, and six pilots, one of whom was borrowed from the 36th Evacuation Hospital since the detachment had only five pilots present for duty. The flight of three arrived at Meadeville at 1400 hours and was met at the airfield by the Reserve Advisors for the area, one of whom was made chief of the ice blasting operations. A reconnaissance flight was made of the ice at 1630 hours that afternoon and the next day, blasting operations began. Reinforcements were brought up via bus from the 19th Engineer Battalion to aid in blasting. The primary duty of the H-19s was to reconnoiter the area and during the last few days to carry 540-pound loads of TNT and drop if from a hover to the demolition team on the ice. The detachment also carried the teams to the ice in inaccessible areas. Cn 9 February the operation was considered accomplished, and the detachment's helicopters were released. One helicopter had been released on 2 February and returned to Fort Meade. Weather kept the remaining party from leaving until 11 February. One aircraft had to remain at Meadville because of engine failure during warm-up.[13][14]

Two pilots flew one of the detachment's aircraft to Atlanta, Georgia for major overhaul. They stopped at Fort Benning, Georgia on the way for a tête-à-tête with the 37th Medical Battalion. On 17 April 1959 the detachment had one medical evacuation from Fort Meade to Valley Forge General Hospital.[13]

In May 1959 the detachment flew an evacuation from Fort Belvoir to Walter Reed Army Medical Center. A Second Army L-20 picked-up the patient at Nassawadox, Virginia and flew him to Ft Belvoir where he was transferred to a waiting H-19.[13]

The detachment flew one aircraft to Atlantic City, New Jersey for 4 days Temporary Duty in conjunction with the American Medical Association Convention and one aircraft to Atlanta, Georgia for SCAMP in June 1959.[13]

On 6 July 1959, the detachment used one aircraft to fly medical supplies to Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania on an emergency run. The detachment also flew one aircraft to Fort Indiantown Gap Pennsylvania to put on a demonstration for the reserve troops in summer training in July.[13]

On 12 August 1959 the detachment sent one aircraft to Bradford, Pennsylvania to pick-up an Army officer injured in an auto accident. He was flown to Fort Meade and transferred to the hospital. Another aircraft spent 3 days at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania carrying an inspection team to Nike sites.[13]

On 18 August 1959 A Navy family member was evacuated from Bainbridge Naval Center to Bethesda Naval Hospital. The patient had a growth in her throat and could hardly breathe. The Naval doctor accompanying the flight almost had to perform a tracheotomy in the air, but the patient recovered her breathe and made it to the hospital.[13]

On 21 August 1959 the detachment evacuated one patient to Valley Forge General Hospital. This was the same patient brought to Fort Meade from Bradford, Pennsylvania on 12 August.[13]

Medical evacuations increased in September 1959 when a scheduled evacuation run from Carlisle Barracks to Valley Forge General Hospital was initiated - a total of 9 patients were transported this month.[13]

In October 1959, the detachment evacuated a patient with an injured kidney from Chestertown, Maryland to Fort Meade.[13]

In November 1959, flights from Carlisle Barracks to Valley Forge General Hospital were numerous during the month, with 7 patients transported.[13]

As the detachment prepared to transition from H-19s to the first air ambulance detachment to field the HU-1, 1LT John P. Temperilli Jr. returned from the HU-1A Maintenance Course at Fort Worth, Texas and 1LT Paul A. Bloomquist departed for the same course.[13]

Evacuations for the December 1959 decreased, with only 3 patients transported during the month.[13]

Two crews departed for Fort Worth, Texas to pick-up two HU-1As (Tail numbers 58-3022 & 58–3023), they departed Fort Worth on 11 January 1960 to return to Fort Meade HU-1A #3123 developed frost pump trouble in Charlotte, North Carolina.[13]

One crew departed for Fort Worth to pick-up HU-1A tail number 58-3024 and departed Fort Worth for Fort Meade on 21 January 1960.[13]

Two crews departed Fort Worth with HU-1As (Tail numbers 58-3025 and 58–3026) on 26 Jan 60. As of the end of January 1960, the 57th had 5 HU-1As and 4 H-19Ds assigned to the unit.[13]

On 17 February 1960 the detachment performed an emergency evacuation from Bainbridge to Bethesda Naval Hospital. It ended up that 3 aircraft were involved - 1 H-19 and 2 HU-1As. Check-outs began in the HU-1As. Three pilots soloed in the UH-1 during the month, and on 18 February one pilot set a record on time to return to Fort Meade from Felker Army Airfield, 03:35 in two days. This extended time was due to weather - a 40 knot head wind.[13]

On 29 February 1960, the detachment set out for the field. Just prior to completing the tent pitching, the field problem was called off because HU-1A #3024 had a material failure. No injuries were incurred. Damage was $60,000 and probably a new aircraft to replace # 58–3024.[13]

On 5 March the unit started on a routine evacuation mission which turned into a snow emergency at Cambridge, Maryland. Many hours were flown and much rescuing was accomplished.[13]

On 23 March 1960 at 0230 hours the detachment received a call to proceed to Elkins, West Virginia to help search for a downed Air Force plane, Two H-19s left at 0600 that morning. The aircraft was found, but all aboard were killed on impact.[13]

On 30 April, First Lieutenant Bloomquist and Captain Temperilli had the pleasure of flying General Ridgway in the HU-1A. He was impressed.[13]

In May, the unit was alerted to depart for Chile to assist in the disaster caused by an earthquake. All personnel except a rear detachment of one officer and two enlisted deployed with four of the detachment's HU-1As.[13]

The operation in Chile and the detachment returned home on 25 June 1960.[13]

The 57th Medical Detachment was reorganized and redesignated as the 57th Medical Platoon effective 1 July 1960.[13]

One aircraft and crew participated in TRIPHIBOUS OPERATION at Fort Story, Virginia; demonstrating a simulated medevac to a ship.[13]

The 57th Medical Platoon was redesignated the 57th Medical Detachment on 10 March 1961.[2]

In December 1961 the detachment was notified that it would be participating in an exercise in Asia, but before it deployed, the 82d Medical Detachment was substituted for the 57th, and deployed on Exercise Great Shelf in the Philippines in March 1962.[2]

Operations in Vietnam, 1962–1973

Advisory support, 1962–1964

The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) received its final alert for overseas deployment on 15 February 1962.[15]

Unit aircraft, one officer and five enlisted departed Fort George G. Meade, Maryland on 3 March 1962 for the Brookley Ocean Terminal in Mobile, Alabama. While in Mobile, the detachment's aircraft were processed for overseas shipment, loaded aboard the USNS Crotan, and arrived at Saigon on 20 April 1962.[16][15]

Yellow disk TAT equipment and two enlisted departed Fort Meade on 16 April 1962 and arrived in Saigon on 20 April 1962.[16]

The main body of the 57th's personnel departed Fort Meade on 18 April 1962 and arrived at Nha Trang just before noon on 26 April 1962.[16][15]

The 57th Medical Detachment became operational at Nha Trang on 5 May 1962 when aircraft and fuel became available.[16]

Aircraft were split to station three at Nha Trang and two at Qui Nhon. The detachment did not become operational at Qui Nhon until fuel became available on the 12 June 1962. Lack of information and preparedness when segments of the detachment arrived in South Vietnam was the main reason why operational capability could not be reached sooner than indicated. Contributing factors were a lack of fuel for the aircraft and differences in operational concept as set forth by Letter of Instructions, Headquarters, U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam, dated 24 April 1962, and those set forth by the detachment commander.[16]

The concept of operations as of the end of July 1962, a 3–2 split of aircraft with supporting personnel was feasible and was being carried out with minor difficulties that could be resolved at the detachment level. A major problem area was the lack of adequate communications. The unit's primary mission of on call Emergency Aeromedical Evacuation could not function properly unless the information on where casualties were located could be relayed to the unit so that a response could be immediate relative to personnel becoming casualties.[16]

No real estate was provided for setting up the detachment at Nha Trang Air Base. The detachment acquired its own real estate but still did not have construction for performing maintenance on organic aircraft. As of the end of July 1962, all supplies were under canvas or in Conex containers. Aircraft maintenance was performed in the open and when inclement weather arrived, maintenance ceased, as has been the case when changing three component parts of the aircraft in June 1962.[16]

Requests for action were slow and in one instance had a demoralizing effect on personnel. The request for flight status on one enlisted performing hazardous duty from the time the unit arrived had not been received as of the end of July 1962.[16]

As of 1 October 1962, a lack of logistical support effected the overall operational capability of the detachment. This was further aggravated by being split into two locations. As of 1 October 1962 it was felt that the need existed for such a split, but unless logistical support for aircraft was improved, some consideration would have to be given to employing the detachment in one location to maintain 24-hour operational capability.[17]

As of 1 October 1962, the detachment was authorized five aircraft and had four assigned:

- Aircraft 58-2081 was EDP for 20 items. Time until the aircraft would become flyable was unknown.[17]

- Aircraft 58-3022 was crash damaged, and the time until the aircraft would be replaced was unknown.[17]

- Aircraft 58-3023 was flyable but would be grounded in 45 hours flying time for two items.[17]

- Aircraft 58-3026 was flyable but would be grounded in 23 flying hours for a tail rotor hub assembly.[17]

- Aircraft 58-3055 would be grounded in 6 flying hours for a tail rotor hub assembly. The part had been extended and could not be extended further.[17]

The detachment was housed in tentage at the airfield without adequate facilities for storing supplies or performing maintenance. Coordination with Nha Trang Airbase Commander had been made and a site for a permanent hangar type building had been approved. As of 1 October 1962, a request and recommended plans had been submitted but the status was unknown to the 57th.[17]

The detachment was completely non-operational from 17 November to 14 December 1962. This situation was caused by the turn-in of certain aircraft parts for use by another unit. Until 17 November 1962, the detachment had maintained one aircraft at Nha Trang and one aircraft at Qui Nhon. From 14 November 1962 thru the end of the year the detachment had one aircraft flyable, and it was rotated between the two locations.[18]

As of 31 December 1962, the detachment was authorized five aircraft, assigned four aircraft, and had one aircraft flyable. The aircraft status by tail number was:[18]

- Aircraft 50-2081: Prepared for shipment to the continental United States

- Aircraft 50-3023: Prepared for shipment to the continental United States

- Aircraft 58-3026: Prepared for shipment to the continental United States

- Aircraft 58-3035: Flyable

In early November 1962, the detachment orderly room was moved into a bamboo hut which allowed for more room and ease of working conditions than was afforded by a General-Purpose medium tent. The unit supply was still housed in two GP medium tents which did not provide a good working atmosphere nor acceptable security or storage of unit equipment. No further information on the construction of a hangar and other additional workspace for the detachment was available as of 31 December 1962.[18]

The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) had the mission of aeromedical evacuation in support of United States Armed Forces operations in the Republic of Vietnam. This rather vague and all-encompassing definition gave rise to many questions throughout the country as to who exactly would be evacuated and in what priority. The situation was finally clarified on 4 September 1963 with the publication of United States Army Support Group, Vietnam Regulation 59–1. The regulation established the priority as: U.S. military and civilian personnel; members of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam; and other personnel for humanitarian reasons. This same regulation also established the procedures to be followed for requesting aeromedical evacuation using a standardized nine-line medical evacuation request.[15]

Towards the end of 1963 the fruits of this regulation became apparent as a definite standardized procedure evolved from the positive application of the regulation.[15]

This left the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) responsible for aeromedical evacuation in the II, III and IV Corps Tactical Zones within the limits of USASGV Regulation 59–1, while the United States Marine Corps was responsible for aeromedical evacuation within the I Corps Tactical Zone.[15]

The detachment was organized under Table of Organization and Equipment 8-500C with Change 2. The authorized strength of the detachment was 7 officers and 22 enlisted. The Commanding General of the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam authorized an increase in unit strength from 7 to 10 officers. This was due to the requirement to have two aviators per aircraft when flying in the Republic of Vietnam. A request to modify the unit TO&E had also been submitted.[15]

Beginning in late January 1963, operational support was provided from three separate bases in the country. The headquarters section with three aircraft was located at Tan Son Nhut Airbase in Saigon. Another section was located in the seacoast town of Qui Nhon with one aircraft, while the third section was located inland of Qui Nhon at Pleiku in the central highlands.[15]

The headquarters section supported operations in the III and IV Corps Tactical Zones, while operations in the II Corps Tactical Zone was provided by the sections in Qui Nhon and Pleiku. The two separate locations in the II Corps Tactical Zone were required due to the large geographic area and the rugged mountains in the highlands. The relocation of aircraft was required due to increased Viet Cong activity in the IV Corps Tactical Zone.[15]

in March 1963, a changeover of the detachment's aircraft occurred, with the unit's UH-1As being replaced with UH-1Bs.[15]

The unit remained assigned to the 8th Field Hospital and under the operational control of the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam.[15]

The detachment operated at under TOE strength until April, when an Infantry officer was assigned to augment the crew at Qui Nhon.[15]

In June, that officer was released and three new officers from the Combat arms were assigned on Verbal Orders of the Commanding General, U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam to bring the detachment's total officer strength to ten. One was an Infantry officer, the second an Armor officer, and the third a Warrant Officer aviator.[15]

In October the Warrant Officer rotated home and was replaced by an Armor officer.[15]

Throughout 1963, the enlisted strength of the detachment hovered around the TO&E authorized strength of 23.[15]

Extensive scheduled training operations as understood in most army circles were not included in the detachment's yearly plan from the time they began operations in 1962 until they began training the Republic of Vietnam Air Force in Medical Evacuation Operations in 1970. There were two basic reasons for this. First, the realization that the entire deployment in Vietnam was a continual practical exercise, and second the desire to keep non-essential flights to an absolute minimum. Training focused on pilot and crew preparation and certification for their duties, such as Pilot in Command, Instructor Pilot, and so on, or training in new systems.[15][19][20][21][22][23]

Maintenance support for the detachment's organic aircraft remained above the army's stated minimum goal of 68% aircraft availability during 1963, despite the detachment's heavy workload of 2,094 flying hours for the year. This was especially significant since the detachment was designed to operate from one location but was operating from three for the majority of the year. Close coordination with field maintenance units at the locations where aircraft were stationed through the headquarters section at Tan Son Nhut was a dominant factor in maintaining this achievement. However, the crux of all maintenance support rested with the detachment itself and this was where the problems had to be resolved. A heavy work schedule was maintained to keep as many aircraft as possible available for flight. The major burden fell on the two single-ship sections.[15]

Requests for aeromedical evacuation were channeled through both Army (Combat Operations Center) and Air Force (Air Operations Center) communications systems to the 57th Medical Detachment as directed in USASGV Regulation 59–1. Action on these requests then became the responsibility of the commanding officer of the 57th Medical Detachment.[15]

Requests for aeromedical coverage on airmobile assault operations were forwarded directly from the requesting unit to the 57th Medical Detachment, and the 57th's detachment commander would coordinate with the assaulting unit's chain of command on the mission. The 57th Medical Detachment had, upon request, covered every major operation in the Republic of Vietnam. This coverage was provided by sending one aircraft to the staging area to the assault staging area to either fly with the assault unit or stand by in the staging area. This made immediate response in the area of the assault possible.[15]

During 1963, night medical evacuation had become a regular service of the detachment and by the end of the year was considered its forte. Due to both the detachment's experience and willingness to fly at night most requests for night evacuations came straight to the detachment. An aircraft and crew—a pilot in command, pilot, crew chief, and medic—at all three locations was continually made available for night operations.[15]

Since it was the detachment's policy to accept all legitimate requests for aeromedical evacuation whether day or night, the unit was, de facto, available for aeromedical evacuations on a 24-hour basis.[15]

Major evacuation for U.S. casualties was provided in the Saigon area. These patients were brought directly to the Tan Son Nhut airfield whenever feasible. On assault operation coverage, medical aid was usually first administered to the casualty by the Medical Corps officer that accompanied the assaulting unit into the staging area.[15]

Vietnamese casualties were usually transported to the nearest field hospital. If further evacuation to the rear was requested by Vietnamese medical personnel and was not contrary to USASCV Regulation 59–1, the request was honored.[15]

Patient care as provided by the 57th Medical Detachment in 1963 consisted mainly of in-flight and emergency medical treatment. Many times, this treatment was the very first the casualty received and consequently turned out to be a definite lifesaving step. The flight medic also provided limited first aid to patients waiting in the staging areas for further rearward evacuation when time permitted.[15]

Throughout the war, although medical evacuation of patients constituted the major workload for the detachment, there were considerable missions in other areas. Aeromedical evacuation helicopters provided coverage for armed and troop transport helicopters during combat heliborne assaults, U.S. Air Force defoliation missions, training parachute jumps, convoys of troop and equipment carrying vehicles, and transport of key medical personnel and emergency medical material.[19][20]

Of the many problems evolving from the operation of any unit, there is one that usually stands before all others. The foible that plagued the 57th Medical Detachment was that of providing total aeromedical coverage to both American and Vietnamese combatants and noncombatants in the Republic of Vietnam. Although the Vietnamese were responsible for evacuating their own casualties, many contingencies came into play that prevented them from doing so, such as large numbers of casualties, lack of sufficient aircraft, or large areas to be covered. To better enable the 57th Medical Detachment to provide this vital coverage, it was necessary to split the unit into three operational sections. This resulted in coverage of a greater area, but also resulted in reduced coverage in Saigon and areas further South. However, this was regarded as the lesser of the two operational constraints.[15]

This then was the nature of the problem. As evacuation assets were arrayed in 1963, many of the aviation companies were forced to provide tactical aircraft to supplement aeromedical aircraft whenever helicopter ambulances of the 57th Medical Detachment were not available due to either prior commitments or the restrictions imposed by aircraft maintenance. This condition would be relieved to a great extent by the augmentation of another helicopter ambulance unit. At the end of 1963 a study was in preparation by the United States Army Support Group, Vietnam to evaluate such a proposal.[15]

Another area that caused problems for the 57th Medical Detachment in 1963 was the matter of having to justify the unit's existence to higher headquarters on the basis of yearly flying hours. This was interpreted by the 57th to mean that a unit's worth was solely dependent on the number of hours flown in a given period and not in the actual accomplishments of the unit—for example, the number of patients evacuated or lives saved. This demonstrated that some individuals did not fully understand the real value of having a trained aeromedical evacuation unit available for immediate response to evacuation requests. Since the detachment performed missions for medical evacuation only, the yearly flight time on aircraft depended solely on the number of evacuations requested. Unlike other aviation units, no administrative or logistical missions were performed, and consequently, the detachment's flight time was less than most other units then serving in the Republic of Vietnam. Because of this shortcoming, another study was directed by the U.S. Support Group, Vietnam to determine the feasibility of integrating the 57th Medical Detachment with those of other logistical units for the purpose on increasing its effectiveness.[15]

The last problem area identified in 1963 that was worth of mention was that concerning maintenance. As mentioned above, the problem was a result of operating from three distinct sections at Qui Nhon, Pleiku, and Saigon. To maintain a flyable aircraft at all times in all sections required more man hours than if the aircraft were concentrated in one location. Thus, a heavier than normal schedule was required by the maintenance personnel at all locations. Despite this, at times no amount of manpower could an aircraft flyable and in this case another aircraft would have to be borrowed from a unit in the immediate vicinity, The limitations on this type of arrangement are readily apparent. The detachment's recommended solution was the deployment of a second air ambulance detachment to Vietnam and the concentration of the 57th's aircraft at one location.[15]

During its first year in country, the 57th worked without a tactical call sign, simply using "Army" and the tail number of the aircraft. For example, if a pilot were flying a helicopter with the serial number 62-12345, his call sign would be "Army 12345". The 57th communicated internally on any vacant frequency it could find. Major Lloyd Spencer, the 57th's second detachment commander in Vietnam, decided that this improvised system needed to be replaced by something more formal. He visited the Navy Support Activity, Saigon, which controlled all the call signs in South Vietnam. He received a Signal Operations Instructions book that listed all the unused call signs. Most, like "Bandit", were more suitable for assault units than for medical evacuation units. But one entry, "Dust Off", epitomized the 57th's medical evacuation missions. Since the countryside then was dry and dusty, helicopter pickups in the fields often blew dust, dirt, blankets, and shelter halves all over the men on the ground. By adopting "Dust Off", Spencer found for Army aeromedical evacuation in Vietnam a name that lasted the rest of the war.[24]: 29

Although unit callsigns at the time were rotated periodically to preserve operations security, it was determined that having a fixed callsign for medical evacuation—and a fixed frequency—would be more advantageous for medical evacuation operations, and so the 57th's callsign was not changed as it normally would have been at the end of the period for the Signal Operations Instructions.

January 1964 found the 57th Medical Detachment located at Tan Son Nhut airport, Saigon. Two air ambulances and crews were attached to the 52d Aviation Battalion, with one helicopter and crew each located at Pleiku and Qui Nhon to provide aeromedical evacuation support within the II Corps area. The remaining three air ambulances and personnel were attached to the 45th Transportation Battalion at Tan Son Nhut providing aeromedical evacuation support within the III and IV Corps areas.[25]

The mission of the detachment was to provide aeromedical evacuation support to U.S. Forces in the Republic of Vietnam and aeromedical evacuation assistance to the Republic of Vietnam as requested. Before the month of January ended the unit was detached from the 145th Aviation Battalion (previously the 45th Transportation Battalion) and attached to Headquarters Detachment, United States Army Support Group, Vietnam. As a result of the new attachment to Headquarters Detachment, U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam, the unit enlisted personnel moved into new quarters in the Support Group Compound.[25]

During the latter part of February consideration was given to relocating the Flight Section in the II Corps area to the IV Corps area because of increased activity in the lower Mekong Delta. This trend of increased activity in IV Corps continued and consequently on 1 March, Detachment A, 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance), (Provisional), was organized and stationed at Sóc Trăng Airfield with attachment to the Delta Aviation Battalion. This reorganization and relocation placed two aircraft with crews in Soc Trang with the remaining aircraft and personnel located at Tan Son Nhut. A sharp increase in the number of patients evacuated during the month of March demonstrated that the relocation was well justified. The increase of patients evacuated in March initiated an upward trend that reached a peak in July with 768 patients evacuated.[25]

With the upward trend in flight time, patients evacuated, and missions flown there was also a corresponding undesirable upward trend in the number of aircraft hit by enemy fire. On 3 April 1964, First Lieutenant Brian Conway had the dubious distinction of being the first Medical Service Corp Aviator to be wounded in action in Vietnam. A .30-caliber round passed through his ankle as he terminated an approach into a field location for a patient pick-up. This wound resulted in Lt. Conway's evacuation to the United States.[25]

Other statistics which reflected an upward trend during the spring and early summer of 1964 were night flying time and missions. The evacuation of patients at night became routine. These missions were accomplished with a single helicopter flying blackout. It was interesting to note that throughout the entire year, only one hit was received at night although searching fire was often observed. Much of the success of the detachment's night operations was due to the excellent U.S. Air Force radar coverage of the III and IV Corps area. Paris and Paddy Control consistently placed unit aircraft over the target.[25]

Although the number of Vietnamese casualties rose in 1963, the South Vietnamese military refused to set up its own aeromedical evacuation unit. The VNAF response to requests for medical evacuation depended on aircraft availability, the security of the landing zone, and the mood and temperament of the VNAF pilots. If the South Vietnamese had no on-duty or standby aircraft ready to fly a medical evacuation mission, they passed the request on to the 57th. Even when they accepted the mission themselves, their response usually suffered from a lack of leadership and poor organization. Since South Vietnamese air mission commanders rarely flew with their flights, the persons responsible for deciding whether to abort a mission often lacked the requisite experience. As a MACV summary said: "Usually the decision was made to abort, and the air mission commander could do nothing about it. When an aggressive pilot was in the lead ship, the aircraft came through despite the firing. American advisers reported that on two occasions only the first one or two helicopters landed; the rest hovered out of reach of the wounded who needed to get aboard."[24]

An example of the poor quality of VNAF medical evacuation occurred in late October 1963, when the ARVN 2d Battalion, 14th Regiment, conducted Operation LONG HUU II near O Lac in the Delta. At dawn the battalion began its advance. Shortly after they moved out, the Viet Cong ambushed them, opening fire from three sides with automatic weapons and 81 -mm. mortars. At 0700 casualty reports started coming into the battalion command post. The battalion commander sent his first casualty report to the regimental headquarters at 0800: one ARVN soldier dead and twelve wounded, with more casualties in the paddies. He then requested medical evacuation helicopters. By 0845 the casualty count had risen to seventeen lightly wounded, fourteen seriously wounded, and four dead. He sent out another urgent call for helicopters. The battalion executive officer and the American adviser prepared two landing zones, one marked by green smoke for the seriously wounded and a second by yellow smoke for the less seriously wounded. Not until 1215 did three VNAF H-34's arrive over O Lac to carry out the wounded and dead. During the delay the ARVN battalion stayed in place to protect their casualties rather than pursue the retreating enemy. The American adviser wrote later: "It is common that, when casualties are sustained, the advance halts while awaiting evacuation. Either the reaction time for helicopter evacuation must be improved, or some plan must be made for troops in the battalion rear to provide security for the evacuation and care of casualties."[24]

The ARVN medical services also proved inadequate to handle the large numbers of casualties. In the Delta, ARVN patients were usually taken to the Vietnamese Provincial Hospital at Can Tho. As the main treatment center for the Delta, it often had a backlog of patients. At night only one doctor was on duty, for the ARVN medical service lacked physicians. If Dustoff flew in many casualties, that doctor normally treated as many as he could; but he rarely called in any of his fellow doctors to help. In return they would not call him on his night off. Many times at night Dustoff pilots would have to make several flights into Can Tho. On return flights the pilots often found loads of injured ARVN soldiers lying on the landing pad where they had been left some hours earlier. After several such flights few pilots could sustain any enthusiasm for night missions.[24]

Another problem was that the ARVN officers sometimes bowed to the sentiments of their soldiers, many of whom believed that the soul lingers between this world and the next if the body is not properly buried. They insisted that Dustoff ships fly out dead bodies, especially if there were no seriously wounded waiting for treatment. Once, after landing at a pickup site north of Saigon, a Dustoff crew saw many ARVN wounded lying on the ground. But the other ARVN soldiers brought bodies to the helicopter to be evacuated first. As the soldiers loaded the dead in one side of the ship, a Dustoff medical corpsman pulled the bodies out the other side. The pilot stepped out of the helicopter to explain in halting French to the ARVN commander that his orders were to carry out only the wounded. But an ARVN soldier manning a .50-caliber machine gun on a nearby armored personnel carrier suddenly pointed his weapon at the Huey. This convinced the Dustoff crew to fly out the bodies. They carried out one load but did not return for another.[24]

Early in 1964 the growing burden of aeromedical evacuation fell on the 57th's third group of new pilots, crews, and maintenance personnel. The helicopters were still the 1963 UH-1B models, but most of the new pilots were fresh from flight school. Kelly was described as "a gruff, stubborn, dedicated soldier who let few obstacles prevent him from finishing a task." Within six months he set an example of courage and hard work that Dustoff pilots emulated for the rest of the war, and into the 21st Century.[24]

Kelly quickly took advantage of the 57th's belated move to the fighting in the south. On 1 March 1964 the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam ordered the aircraft at Pleiku and Qui Nhon to move to the Delta. Two helicopters and five pilots, now called Detachment A, 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance), Provisional, flew to the U.S. base at Soc Trang. Once a fighter base for both the French and the Japanese, Soc Trang was a compound roughly 1,000 by 3,000 feet, surrounded by rice paddies.[24]

Unit statistics soon proved the wisdom of the move south: the number of Vietnamese evacuees climbed from 193 in February to 416 in March. Detachment A continued its coverage of combat in the Delta until October 1964, when the 82nd Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) from the States took over that area. Major Kelly, who had taken command of the 57th on 11 January, moved south with Detachment A, preferring the field and flying to ground duty in Saigon.[24]

Detachment A in Soc Trang lived in crude "Southeast Asia" huts with sandbags and bunkers for protection against enemy mortar and ground attack. The rest of the 57th in Saigon struggled along with air conditioning, private baths, a mess hall, and a bar in their living quarters. In spite of the contrast, most pilots preferred Soc Trang. It was there that Major Kelly and his pilots forged the Dustoff tradition of valorous and dedicated service.[24]

Kelly and his teams also benefited from two years of growing American involvement in Vietnam. By the spring of 1964 the United States had 16,000 military personnel in South Vietnam (3,700 officers and 12,300 enlisted men). The Army, which accounted for 10,100 of these, had increased its aircraft in South Vietnam from 40 in December 1961 to 370 in December 1963. For the first time since its arrival two years ago the 57th was receiving enough Dustoff requests to keep all its pilots busy.[24]

Kelly faced one big problem when he arrived: the helicopters that the 57th had received the year before were showing signs of age and use, and Brigadier General Joseph Stilwell Jr., the Support Group commander, could find no new aircraft for the detachment. Average flight time on the old UH-1Bs was 800 hours. But this did not deter the new pilots from each flying more than 100 hours a month in medical evacuations. Some of them stopped logging their flight time at 140 hours, so that the flight surgeon would not ground them for exceeding the monthly ceiling.[24]

The new team continued and even stepped-up night operations. In April 1964, the detachment flew 110 hours at night while evacuating ninety-nine patients. To aid their night missions in the Delta the pilots made a few special plotting flights, during which they sketched charts of the possible landing zones, outlined any readily identifiable terrain features, and noted whether radio navigational aid could be received. During one such flight Major Kelly and his copilot heard on their radio that a VNAF T-28, a fixed-wing plane, had gone down. After joining the search, Kelly soon located the plane. While he and his crew circled the area trying to decide how to approach the landing zone, the Viet Cong below opened fire on the helicopter. One round passed up through the open cargo door and slammed into the ceiling. Unfazed, Kelly shot a landing to the T-28, taking fire from all sides. Once down, he, his crew chief, and his medic jumped out and sprayed submachine gun fire at the Viet Cong while helping the VNAF pilot destroy his radios and pull the M60 machine guns from his plane. Kelly left the area without further damage and returned the VNAF pilot to his unit. Kelly and his Dustoff crew flew more than 500 miles that day.[24]

On 2 April one of the Detachment A crews flying to Saigon from Soc Trang received a radio call that a village northwest of them had been overrun. Flying up to the area where the Mekong River flows into South Vietnam from Cambodia, they landed at the village of Cai Cai, where during the night Viet Cong had killed or wounded all the people. Soldiers lay at their fighting positions where they had fallen, women and children where they had been shot. The Dustoff teams worked the rest of the day flying out the dead and wounded, putting two or three children on each litter.[24]

One night that spring Detachment A pilots Capt. Patrick Henry Brady and 2d Lt. Ernest J. Sylvester were on duty when a call came in that an A1-E Skyraider, a fixed-wing plane, had gone down near the town of Rach Gia. Flying west to the site, they radioed the Air Force radar controller, who guided them to the landing zone and warned them of Viet Cong antiaircraft guns. As the Dustoff ship drew near the landing zone, which was plainly marked by the burning A1-E, the pilot of another nearby Al-E radioed that he had already knocked out the Viet Cong machine guns. But when Brady and Sylvester approached the zone the Viet Cong opened fire. Bullets crashed into the cockpit and the pilots lost control of the aircraft. Neither was seriously wounded and they managed to regain control and hurry out of the area. Viet Cong fire then brought down the second Al-E. A third arrived shortly and finally suppressed the enemy fire, allowing a second Dustoff ship from Soc Trang to land in the zone. The crew chief and medical corpsman found what they guessed was the dead pilot of the downed aircraft, then found the pilot of the second, who had bailed out, and flew him back to Soc Trang.[24]

A short time later Brady accompanied an ARVN combat assault mission near Phan Thiet, northeast of Saigon. While Brady's Dustoff ship circled out of range of enemy ground fire, the transport helicopters landed and the troops moved out into a wooded area heavily defended by the Viet Cong. The ARVN soldiers immediately suffered several casualties and called for Dustoff. Brady's aircraft took hits going into and leaving the landing zone, but he managed to fly out the wounded. In Phan Thiet, while he was assessing the damage to his aircraft, an American adviser asked him if he would take ammunition back to the embattled ARVN unit when he returned for the next load of wounded. After discussing the propriety of carrying ammunition in an aircraft marked with red crosses, Brady and his pilots decided to consider the ammunition as "preventive medicine" and fly it into the LZ for the ARVN troops. Back at the landing zone Brady found that Viet Cong fire had downed an L-19 observation plane. Brady ran to the crash site, but both the American pilot and the observer had been killed. The medical corpsman and crew chief pulled the bodies from the wreckage and loaded them on the helicopter. Brady left the ammunition and flew out with the dead.[24]

By the time the helicopter had finished its mission and returned to Tan Son Nhut, most of the 57th were waiting. News of an American death traveled quickly in those early days of the war. Later, reflecting on the incident, Kelly praised his pilots for bringing the bodies back even though the 57th's mission statement said nothing about moving the dead. But he voiced renewed doubts about the ferrying of ammunition.[24]

Brady later explained what actually happened behind the scenes. Upon landing, Brady was met by Kelly and called aside. Expecting to be sternly counseled, Brady was surprised when Kelly simply asked why he had carried in ammunition and carried out the dead. Brady replied that the ammunition was "preventive medicine" and that the dead "were angels", and he couldn't refuse them. Kelly simply walked back to the group involved in that day's missions and told them that it was the type of mission he wanted the 57th to be flying. Brady realized the significance of Kelly's statement, as Kelly would be responsible for any fallout from Brady's actions.[26]

In fact, the Dustoff mission was again under attack. When Support Command began to pressure the 57th to place removable red crosses on the aircraft and begin accepting general purpose missions, Kelly stepped up unit operations. Knowing that removable red crosses had already been placed on transport and assault helicopters in the north, Kelly told his men that the 57th must prove its worth-and by implication the value of dedicated medical helicopters-beyond any shadow of doubt.[24]

While before the 57th had flown missions only in response to a request, it now began to seek missions. Kelly himself flew almost every night. As dusk came, he and his crew would depart Soc Trang and head southwest for the marshes and Bac Lieu, home of a team from the 73d Aviation Company and detachments from two signal units, then further south to Ca Mau, an old haunt of the Viet Minh, whom the French had never been able to dislodge from its forested swamps. Next, they would fly south almost to the tip of Ca Mau Peninsula, then at Nam Can reverse their course toward the Seven Canals area. After a check for casualties there at Vi Thanh, they turned northwest up to Rach Gia on the Gulf of Siam, then on to the Seven Mountains region on the Cambodian border. From there they came back to Can Tho, the home of fourteen small American units, then up to Vinh Long on the Mekong River, home of the 114th Aviation Company (Airmobile Light). Finally, they flew due east to Truc Giang, south to the few American advisers at Phu Vinh, then home to Soc Trang. The entire circuit was 720 kilometers.[24]

If any of the stops had patients to be evacuated, Kelly's crew loaded them on the aircraft and continued on course, unless a patient's condition warranted returning immediately to Soc Trang. After delivering the patients, they would sometimes resume the circuit. Many nights they carried ten to fifteen patients who otherwise would have had to wait until daylight to receive the care they needed. In March, this flying from outpost to outpost, known as "scarfing", resulted in seventy-four hours of night flying that evacuated nearly one-fourth of that month's 448 evacuees. The stratagem worked; General Stilwell dropped the idea of having the 57th use removable red crosses.[24]

Although most of Dustoff's work in the Delta was over flat, marshy land, Detachment A sometimes had to work the difficult mountainous areas near the Cambodian border. Late on the afternoon of 11 April Kelly received a mission request to evacuate two wounded ARVN soldiers from Phnom Kto Mountain of the Seven Mountains of An Giang Province. When he arrived he found that the only landing zone near the ground troops was a small area surrounded by high trees below some higher ground held by the Viet Cong. Despite the updrafts common to mountain flying, the mists, and the approaching darkness, Kelly shot an approach to the area. The enemy opened fire and kept firing until Kelly's ship dropped below the treetops into the landing zone. Kelly could set the aircraft down on only one skid; the slope was too steep. Since only one of the wounded was at the landing zone, Kelly and his crew had to balance the ship precariously while waiting for the ARVN troops to carry the other casualty up the mountain. With both patients finally on board, Kelly took off and again flew through enemy fire. The medical corpsman promptly began working on the Vietnamese, one of whom had been wounded in five places. Both casualties survived.[24]

When Kelly flew such a mission he rarely let bad weather darkness, or the enemy stop him from completing it. He fought his way to the casualties and brought them out. On one mission the enemy forced him away from the landing zone before he could place the patients on board. An hour later he tried to land exactly the same way, through enemy fire, and this time he managed to load the patients safely. The Viet Cong showed their indifference to the red crosses on the aircraft by trying to destroy it with small arms, automatic weapons, and mortars, even while the medical corpsman and crew chief loaded the patients. One round hit the main fuel drain valve and JP-4 fuel started spewing. Kelly elected to fly out anyway, practicing what he had preached since he arrived in Vietnam by putting the patients above all else and hurrying them off the battlefield. He radioed the Soc Trang tower that his ship was leaking fuel and did not have much left, and that he wanted priority on landing. The tower operator answered that Kelly had priority and asked whether he needed anything else. Kelly said, "Yes, bring me some ice cream." just after he landed on the runway the engine quit, fuel tanks empty. Crash trucks surrounded the helicopter. The base commander drove up, walked over to Kelly, and handed him a quart of ice cream.[24]

Apart from the Viet Cong, the 57th's greatest problem at that time was a lack of pilots. After Kelly reached Vietnam he succeeded in having the other nine Medical Service Corps pilots who followed him assigned to the 57th. He needed more, but the Surgeon General's Aviation Branch seemed to have little understanding of the rigors of Dustoff flying. In the spring of 1964 the Aviation Branch tried to have new Medical Service Corps pilots assigned to nonmedical helicopter units in Vietnam, assuming that they would benefit more from combat training than from Dustoff flying.[24]

On 15 June 1964, Kelly gave his response:

"As for combat experience, the pilots in this unit are getting as much or more combat-support flying experience than any unit over here. You must understand that everybody wants to get into the Aeromedical Evacuation business. To send pilots to U.T.T. [the Utility Tactical Transport Helicopter Company, a nonmedical unit] or anywhere else is playing right into their hands. I fully realize that I do not know much about the big program, but our job is evacuation of casualties from the battlefield. This we are doing day and night, without escort aircraft, and with only one ship for each mission. Since I have been here we have evacuated 1800 casualties and in the last three months we have flown 242.7 hours at night. No other unit can match this. The other [nonmedical] units fly in groups, rarely at night, and always heavily armed."[27]

He continued:

"If you want the MSC Pilots to gain experience that will be worthwhile, send them to this unit. It is a Medical Unit and I don't want to see combat arms officers in this unit. I will not mention this again. However, for the good of the Medical Service Corps Pilots and the future of medical aviation I urge you to do all that you can to keep this unit full of MSC Pilots."[27]

In other words, Kelly thought that his unit had a unique job to do and that the only effective training for it could be found in the cockpit of a Dustoff helicopter.[24]

Perhaps presciently, Kelly closed his letter as follows:

"Don't go to the trouble of answering this letter for I know that you are very busy. Anyhow, everything has been said. I will do my best, and please remember 'Army Medical Evacuation FIRST'."[27]

With more and more fighting occurring in the Delta and around Saigon, the 57th could not always honor every evacuation request. U.S. Army helicopter assault companies were forced to keep some of their aircraft on evacuation standby, but without a medical corpsman or medical equipment. Because of the shortage of Army aviators and the priority of armed combat support, the Medical Service Corps did not have enough pilots to staff another Dustoff unit in Vietnam. Most Army aeromedical evacuation units elsewhere already worked with less than their permitted number of pilots. Although Army aviation in Vietnam had grown considerably since 1961, by the summer of 1964 its resources fell short of what it needed to perform its missions, especially medical evacuation.[24]

Army commanders, however, seldom have all the men and material they can use, and Major Kelly knew that he had to do his best with what he had.[24]

Kelly had begun to realize that, although he preferred flying and being in the field to Saigon, he could better influence things by returning to Tan Son Nhut. After repeated requests from Brady, Kelly told him that he would relinquish command of Detachment A of the 57th at Soc Trang to Brady on 1 July and return to Saigon—although he then later told Brady he was extending his stay in the Delta for at least another month.[26]

The second half of the year began with the sad event of the death of the detachment commander, Major Charles L. Kelly on 1 July 1964. He was struck in the chest by a Viet Cong bullet while attempting a patient pick-up. The aircraft crashed with the other three crewmembers receiving injuries.[25] His dying words, "When I have your wounded," would become both a creed and rallying cry for both the 57th and all other Dustoff units to follow them.

Captain Paul A. Bloomquist assumed command of the detachment and remained as commander until the arrival of Major Howard A. Huntsman Jr. on 12 August.[25]

Evacuation workload began a downward toward trend in August from the high reached in July. September showed a slight gain over August, but the trend downward continued for the remainder of the year. Two factors were pertinent in the downward trend. First, the Vietnamese Air Force began playing an increasing role in the evacuation of Vietnamese patients. Although the evacuation of Vietnamese personnel was a secondary mission this in reality constituted the major portion of the workload for the 57th. The second factor was the arrival of the 82d Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) in October. This detachment was located in Soc Trang. This relieved Detachment A of the 57th and the unit was reconsolidated as a complete unit at Tan Son Nhut on 7 October 1964. This was the first time that the unit had operated from one location in entirety since its arrival in Vietnam.[25]

There was a personnel exchange between the 82nd and the 57th. This involved six officers and was accomplished in order to better distribute rotation dates for the 82d Medical Detachment. Four enlisted personnel were also exchanged. Transferred from the 82d to the 57th were Captain Raymond A. Jackson, Captain Douglas E. Moore, and Lieutenant John J. McGowan. Transferred to the 82nd were Lieutenant Armond C. Simmons, Lieutenant Ernest J. Sylvester, and Lieutenant Bruce C. Zenk.[25]

In October the detachment was relieved from attachment to Headquarters Detachment, U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam and attached to the 145th Aviation Battalion for rations and quarters. This involved a move of both officer and enlisted personnel into new quarters with the 145th Aviation Battalion. This resulted in an upgrading in living conditions which was appreciated by all.[25]

Although the evacuation of patients was to constitute the major workload for the unit, there was considerable workload in other allied areas. Aeromedical evacuation helicopters of the unit provided medical coverage for armed and troop transport helicopter during air assaults. As a result, the unit has been involved in every air mobile operation in the III Corps area, and in the IV Corps area until relieved of that responsibility by the 82nd MD (HA) in October. Medical coverage was also provided to aircraft engaged in the defoliation mission. This became almost a daily activity in the last few months of the year. Unit aircraft also became involved in many search and rescue missions. This often led to the depressing job of extracting remains from crashed aircraft.[25]

Early in the month of December unit aircraft and crews became engaged in airmobile operation and evacuation missions in the Bình Giã area which was southeast of Saigon. By the end of December operations in this area had expanded to near campaign proportions and unit aircraft were committed on nearly a daily basis. The end of the year 1964 was met with a sense of accomplishment by all unit personnel. The 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) had performed well and accomplished much.[25]

The build-up, 1965–1967

By 1965, the mission of the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) was established as "to provide medical air ambulance support within capabilities to U.S. and Free World Military Assistance Forces (FWMAF) personnel, and back-up service to Republic of Vietnam Air Force (VNAF) personnel as directed within III Corps Tactical Zone, ARVN 7th Division Tactical Zone within the IV Corps Tactical Zone, and back-up support for the 498th Medical Company (Air Ambulance) operating within the II Corps Tactical Zone in coordination with the Commanding Officers of the 254th and 283d Medical Detachments (Helicopter Ambulance)." Their responsibilities included:[19]

- Providing aeromedical evacuation of patients, including in-flight treatment and/or surveillance, in accordance with established directives, from forward combat elements or medical facilities as permitted by the tactical situation to appropriate clearing stations and hospitals, and between hospitals as required.[19]

- Providing emergency movement of medical personnel and material, including blood, in support of military operations in zone.[19]

Although the units supported, and the units they coordinated with, would change from year to year, the mission remained essentially unchanged until the detachment redeployed form Vietnam in 1973.

At the end of 1965, the detachment was awaiting approval of its request to be reorganized under TO&E 8-500D which would authorize six UH-1D helicopter ambulances and a corresponding increase in aviator and enlisted personnel. The 8-500C TO&E authorized only 5 aircraft.[19]

General Order Number 75, Headquarters, 1st Logistical Command, dated 13 December 1965, organized the Medical Company (Air Ambulance) (Provisional) and assigned the new company the mission of providing command and control of the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) in the aeromedical evacuation support of counterinsurgency operations within the III and IV Corps Tactical Zones. The company was created in response to the obvious need for a command and control headquarters.[19]

The personnel authorized under TO&E 8-500C with Change 2 was augmented by General Order Number 143, Headquarters, U.S. Army Pacific, dated 31 July 1964. This augmentation increased the unit strength by three additional Medical Service Corps Aviators, MOS 1981, which brought the total authorization for the detachment to ten aviators. This allowed the detachment to meet the command requirement that each aircraft have two aviators aboard for each flight. This was considered essential in combat flying and especially so in Vietnam in order that one aviator would be available to take control of the aircraft in the event the other was hit by enemy fire and was not a requirement in the continental United States when the UH-1 was fielded.[19]

Under the reorganization the detachment had pending on 31 December 1965, authorized aviator personnel would increase to eight rotary wing aviators, which would have to be augmented by four additional aviators to meet the command requirement of two aviators per aircraft. A proposed TOE Unit Change Request would be submitted upon reorganization which would increase the total number of authorized aviators to fourteen, providing for a full complement of medical evacuation pilots plus a commander and operations officer.[19]

Enlisted personnel strength remained at a satisfactory level throughout 1965, which was considered an essential factor to the accomplishment of the unit's mission. A full complement of qualified aircraft maintenance personnel and senior medical aidmen was constantly required as they participated in every evacuation flight.[19]

Aircraft maintenance support and availability of spare parts required to maintain unit aircraft in operational status was adequate, considering the increased load placed on both maintenance facilities and aircraft parts because of the influx of aviation units into Vietnam in 1965. Aircraft availability averaged 86% for the year.[19]

Air evacuation of casualties in the Republic of Vietnam was routine in 1965, as highway insecurity and frequent enemy ambushes along traveled routes prohibited evacuation by ground vehicles.[19]